Below is a guest post from my friend and frequent podcast guest, Scott Young. Scott has taken on some crazy projects over the years to learn different skills. This includes his MIT Challenge, where he crammed the content of an MIT degree into a year of study at home (without paying a cent in tuition) and traveling around the world to learn four languages in a year.

He recently published a book, Ultralearning, documenting how he does it. The book shares a lot of stories of people who have transformed their careers, started businesses, and mastered hard skills using this approach.

In these extra-uncertain times, I asked Scott if he could explain how you might be able to get ahead without needing to go back to school.

Enter Scott…

Being able to teach yourself hard skills is an incredible asset. School has never been more expensive and a lot of what you learn in college isn’t directly useful in your career. Master new skills quickly and you’ll never run out of opportunities.

But this is often easier said than done. For starters, how do you know which skills you ought to learn? Just being good at something doesn’t mean it will earn a living. Just ask any struggling artist or musician.

Even if you do pick the right skill, teaching yourself isn’t easy. Most give up or get stuck long before their newfound abilities manage to pay off.

In researching my book Ultralearning, I met dozens of people who have built impressive careers from self-acquired skills. Here are the not-so-obvious tips to get it right.

How to Pick Skills that Matter

The first step is to pick skills that will reliably advance your career (or help you start a new one). This is also the step most people screw up.

Instead of researching their career path and identifying exactly where to invest their efforts, most people pick haphazardly. Maybe they’re driven by curiosity. Or they read a news article about a new field that’s “hot.” Either way, they’re just guessing.

A far better strategy is to use the Expert Interview Method. The strategy is simple:

- Pick someone two to three steps ahead of you, in the field or career you want. If you’re contemplating a career hop, find someone two to three years into that career already. If you’re trying to move up to the next level in your current career, find someone who has the kind of job you’d like to get.

- Ask to interview them, paying particular attention to their career path. What kind of projects did they work on? What enabled them to move forward? What did they have to be good at to be seen as successful at their job?

- Deconstruct which skills are likely required for you to make a similar move. Sometimes this is plainly obvious. You want to get into web development, so you talk to someone who built her own website before getting hired. In other cases, it requires some deductive reasoning. The manager who moved up might have had sharp project management skills, or was a persuasive presenter to recruit support to his team.

Even if you don’t get a crystal clear answer about what you ought to learn, this process weeds out a lot of bad choices. Getting a feel for which skills separate great candidates from mediocre ones gives you an edge in investing your efforts.

How to Master Key Skills

Once you’ve picked the skill you want to improve, how should you learn it?

I suggest defining a concrete project, over a specific timeframe. Training efforts have a tendency to fizzle out, particularly if they’re not urgent. Yes, getting a better career may make a huge difference in your life, but failing to do so is often invisible. Making a clear project puts the effort in the front of your mind and your calendar.

Thirty or sixty days is a good chunk of time. Not all career skills can be learned in such a short time, but breaking down a big skill into month-long chunks is useful nonetheless. This forces you to be ultra-specific and prevents getting distracted by all the possible things you could learn.

The two most important parts of the project are how much time and effort you intend to invest and how you’re going to limit the scope. For instance:

- Excel. I’m going to spend 30 minutes a day, every morning improving my Excel skills. I’m going to do this by following a course plus implementing each idea in my own work.

- Presenting. I’m going to go to two Toastmaster meetings per week and complete at least four prepared speeches in the next sixty days.

- Video Editing. I’m going to learn how to use Final Cut and create a portfolio of at least three finished videos.

The Best Strategy for Learning

With a project in place, what’s the most effective way to learn?

Again, there’re a few common mistakes people engage in that keep them from learning. In my book, I found there were nine principles that underpinned successful projects. Here’s a few of them to keep in mind:

Directness — Be ultra-specific in what you intend to learn.

Transfer is the ability to take something you learn in one context, say a book or a class, and apply it to a different context, say in real life. The evidence is overwhelming that this is much more difficult than people typically assume.

Countless studies show that people often fail to transfer things they learn, even when we have a strong expectation that they will. For instance, one study found those who took economics classes didn’t do better on economic reasoning problems. Another found students who took a high-school psychology class didn’t get better grades when they later took college-level psychology.

While it’s tempting to blame education, the narrowness of acquired skills is typical. The solution is to be explicit about what you want to learn and practice that directly. There are a few ways you can use this to your advantage:

- Ask yourself what exactly is the skill you need to perform to be valuable for your job. An aspiring architect I interviewed got his first job after training on the exact software used in firms, designing a building that matched the format of real blueprints. Both of these were far from the abstract design training he had received in college.

- If you’re learning something abstract, say marketing or project management, make an effort to deliberately ask how it would apply to the situation you’re trying to learn about. This will make it easier later to use that knowledge in an interview or new project.

- Building something is often a great way to ensure you’ve learned something practical, not just read a lot of tutorials. If you can create a program, prototype, or performance following your new skill, that’s evidence to others that you can actually deliver on your resume.

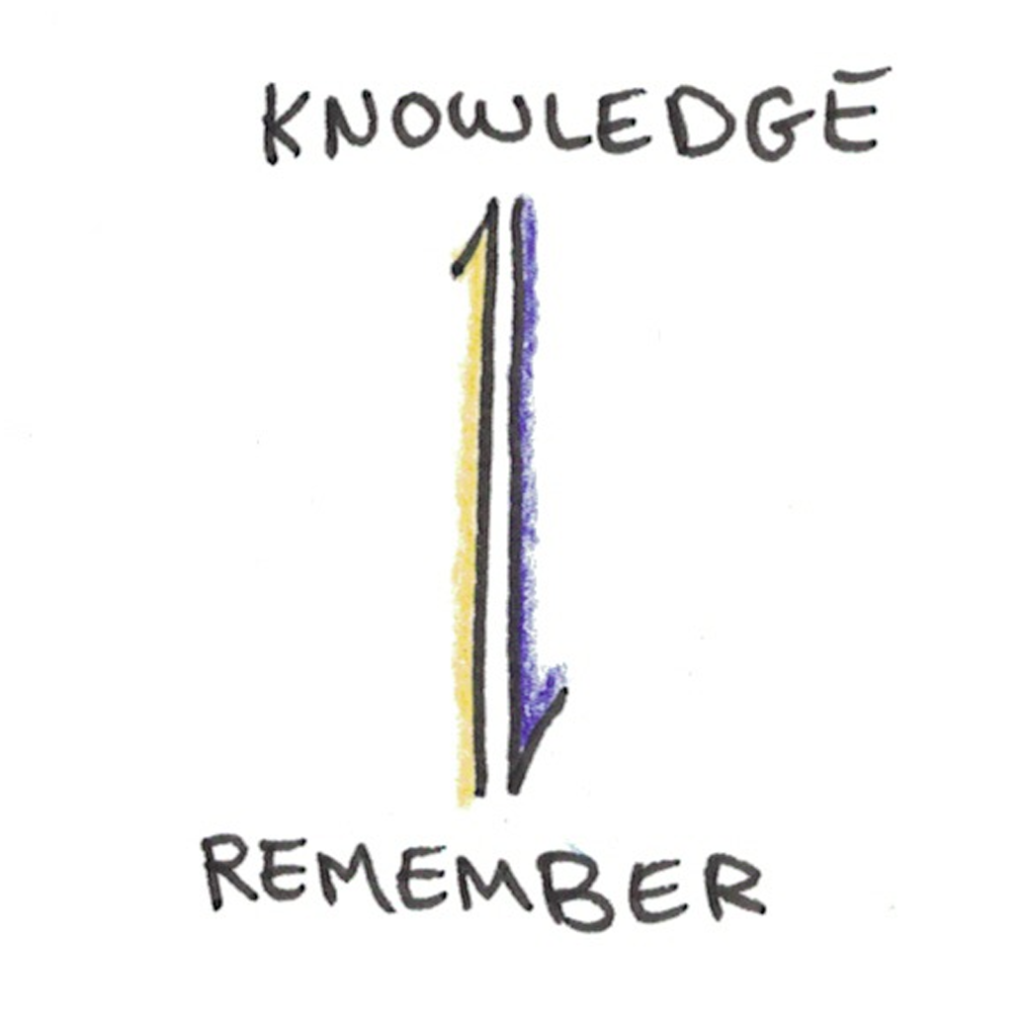

Retrieval — Don’t just read and listen.

Another common mistake is to equate reviewing with effective studying. Cognitive science research makes a big distinction between studying methods that require retrieval and those that don’t.

Consider one study where participants had to learn a text. They were split into four groups: reading the text once, reading it multiple times, reading it once and trying to remember what was in it, and drawing a concept map. Who do you suppose did best?

Interestingly, the study authors asked the students how they thought they did. Those who read the text multiple times thought they would do best, while those who read it only once and spent the rest of the time trying to remember what was in it thought they’d do the worst.

The results were the opposite. Those who spent their time trying to retrieve the information from memory, not those who re-read multiple times, did best on the actual test.

So how can you use this to your advantage? The key is that when you practice a new skill, there is a lot of knowledge that needs to be at your fingertips to perform well. You can master that knowledge more quickly if you practice in a way so that you can’t look at what the answer is immediately. If you look it up only after attempting to recall it yourself, it will be remembered much better.

This works for learning Excel functions, tools in Photoshop, or for memorizing a speech. If you need it to perform, retrieval will help you learn it more deeply.

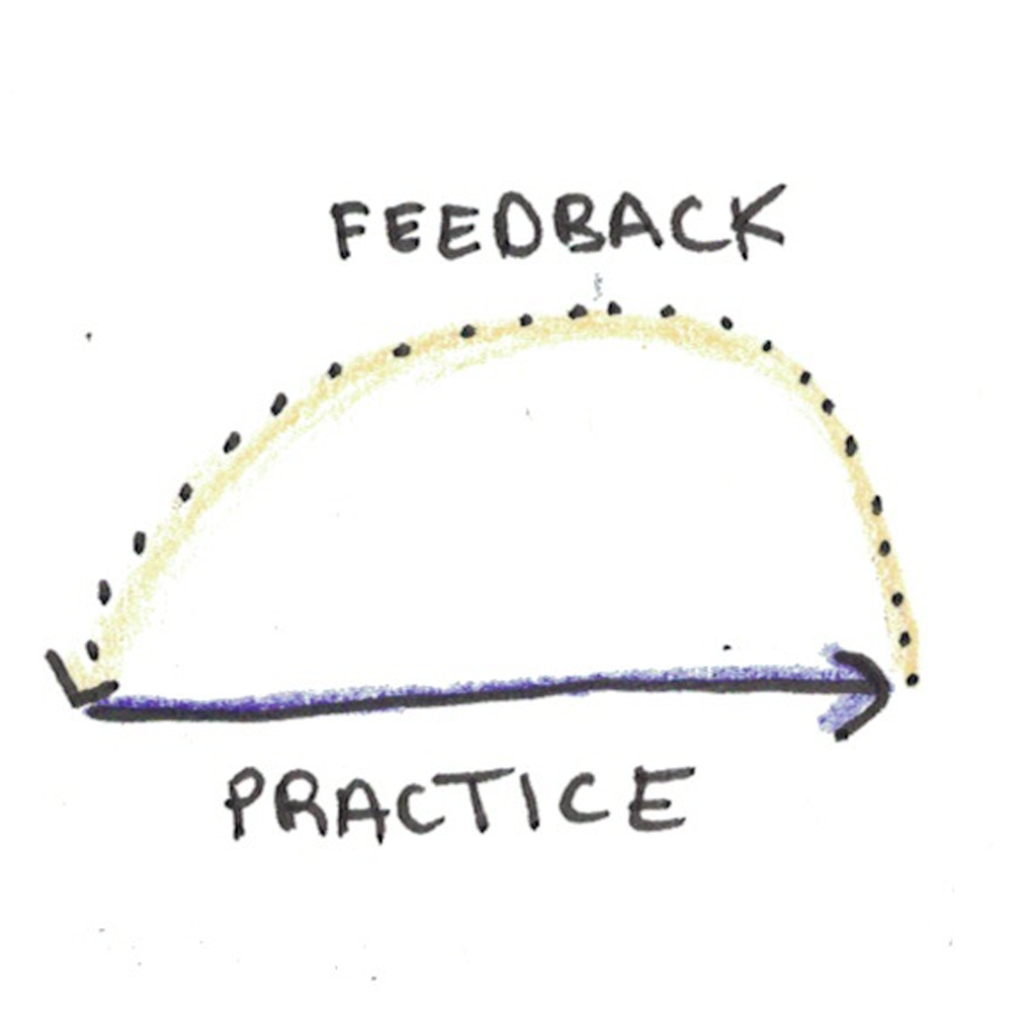

Feedback — Discover your weak points.

Feedback is essential for learning hard skills well. But there’s a lot of misconceptions surrounding it.

Many people assume more feedback is always better, but the research doesn’t support this. In a meta-analysis combining many studies on the impact of feedback interventions in learning, researchers Avraham Kluger and Angelo DeNisi found that in over a third of studies, feedback actually hurt.

The reason is that feedback needs to be constructive to help. We understand this in terms of harsh criticism that doesn’t motivate (“You’ll never be good at this — just give up now!”). But the authors note that even praise, which is popular with both teachers and students has a negative impact. “You’re so great!” becomes a signal to stop trying to improve more.

To be effective, feedback ought to be aimed at how to make improvements in the task itself and not at you as a person.

Learning How to Learn

The benefit of a single skill itself can be enormous. I met dozens of people who built entirely new careers, or had major leaps forward in their current profession, just by adding a key skill to their resume. However, such enormous leaps are rare.

A more common pattern is one where learning many related skills eventually makes you uniquely qualified for the best jobs and projects. The goal is not to learn a single, narrow skill, but many skills that overlap and create mastery. Those that pursue this fully often end up being labeled as simply “talented” as others struggle to see how they could have learned it.

You can also become more talented. But to do that you need to invest in learning. More important, you need to invest in learning how to learn — understanding how to make progress. Do this, and you’ll never run out of opportunities.