Sam Harris (@samharrisorg) is a neuroscientist, author, and philosopher; he’s also a staunch critic of religion (while being an advocate of mindfulness) who joins the show to discuss some views that — fair warning — many may find controversial. [Note: This is a previously broadcast episode from the vault that we felt deserved a fresh pass through your earholes!]

What We Discuss with Sam Harris:

- When does stubbornness stop being a virtue and become a confession of intellectual dishonesty?

- In what ways does Sam consider himself a bit of an Anti-Trump?

- Why do so many people subscribe to the package beliefs of their political parties or religions even when clearly proven scientific facts prove contradictory to these beliefs?

- If Sam Harris considers himself primarily a philosopher, how did he wind up with a PhD in neuroscience?

- Why do we lie — even when we know how destructive it can be?

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

He contrasts this approach with Donald Trump, whose carefully curated audience tends to accept whatever he says — even when what he says today contradicts what he said yesterday, or when clear evidence debunks his “facts” as fictions. Does this make Sam Harris the Anti-Trump?

Listen to this episode in its entirety to learn more about why credentials don’t ultimately matter if you’re adept at playing the language game, why Sam Harris is cautious about having his work translated into Arabic, what security measures a controversial author has to take when their life has been threatened by people who have proven themselves dangerous, why we lie (even when we understand how destructive it can be), and lots more. Listen, learn, and enjoy! [Note: This is a previously broadcast episode from the vault that we felt deserved a fresh pass through your earholes!]

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- Thuma: Go to thuma.co/jordan and enter code JORDAN at checkout for a $25 credit

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- Squarespace: Go to squarespace.com/jordan to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain

- Progressive: Get a free online quote at progressive.com

Miss our two-part conversation with the Danish family man who infiltrated the illicit North Korean arms trade? Catch up beginning with episode 527: Ulrich “The Mole” Larsen | Undercover in North Korea Part One here!

On The Mark Divine Show, human potential expert and global change visionary Mark Divine discovers what makes today’s most inspirational, self-aware, and exponential leaders think and act so differently. Listen on PodcastOne or wherever you find fine podcasts!

Thanks, Sam Harris!

If you enjoyed this session with Sam Harris, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Sam Harris at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Sam Harris | Making Sense of the Present Tense | The Jordan Harbinger Show 509

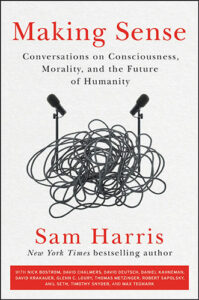

- Making Sense: Conversations on Consciousness, Morality, and the Future of Humanity by Sam Harris | Amazon

- Making Sense Podcast with Sam Harris

- Other Books by Sam Harris | Amazon

- Waking Up | App

- Sam Harris | Website

- Sam Harris | Twitter

- Sam Harris | Instagram

- Sam Harris | Facebook

- Sam Harris | YouTube

698: Sam Harris | Rationally Confronting the Irrational

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:03] Sam Harris: I mean, we're really on the cusp of either a problem has a solution or it doesn't. If we could just cease to needlessly make ourselves miserable by fighting unnecessary wars or having a significant subset of humanity devote their lives to just divisive delusions, we could just get down to the business of maximizing human flourishing. And that I think is really what we should be doing all day long. And their creativity and love and wisdom and good conversations is all we need.

[00:00:38] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We have in-depth conversations with scientists and entrepreneurs, spies and psychologists, even the occasional journalist-turned poker champion, former cult member, drug trafficker, or former Jihadi. Each episode turns our guests' wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better thinker.

[00:01:04] If you're new to the show, or you're looking for a handy way to tell your friends about the show — and I appreciate it when you do that — I suggest our episode starter packs as a beginning point for that. These are collections of some of our favorite episodes organized by topic to help new listeners get a taste of everything that we do here on the show — topics like persuasion, influence, negotiation, communication, China, North Korea, crime and cults, and more. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started.

[00:01:32] Today, one from the vault, we're talking with Sam Harris once again, a conversation that we recorded several years back on a different show. His episodes here on this show have always been super popular. So I'm glad to be doing it again. He's a staunch critic of religion, an advocate of mindfulness without religion, an author, a neuroscientist, a researcher, and an ethicist among other things. Of course, he's also a podcaster. He's an all-around, amazingly sharp, and fascinating thinker and also very controversial. So warm up those angry emailing fingers now, and enjoy this episode from the vault with Sam Harris.

[00:02:08] Tell us what you do in one sentence.

[00:02:11] Sam Harris: Well, I think in public. I try to reason as honestly as possible in public. And I tend to do this on controversial issues.

[00:02:20] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I would agree with that. Well, first of all, you are also a neuroscientist. Let's not leave that behind, studying in part the physiology of belief and belief change, which is something that I think is an entirely different show topic for maybe another day and fascinating looking at people's brains and figuring out where their beliefs are and whether or not they can be changed and how the brain does that or doesn't do that, depending on which book you're reading from, who, from which author. Before we sort of dive into some of the work that I've read from you, I'm very curious, because you do get challenged a lot. You are a controversial character in some ways. How do you keep an open mind during intense debate with people, I should say whom disagree with you, it's such a visceral level that they're actually super angry or can't even keep control of maybe their emotions during that time.

[00:03:09] Sam Harris: Well, I think we should acknowledge that there are two kinds of debate. There are debates that are really not at all meant to the minds or participants go into these debates. Public debates usually have this character, certainly anything that's described as a debate in advance or setup as a debate, often has this character where the two sides are not at all meant to be persuaded by one another. And they're simply trying to persuade an audience and everyone knows that they're playing a game or seeing a public contest, the resolution of which only takes place in the minds of the audience, because you just see people on stage. Even if they're being swayed to whatever degree, they're pretending that they're not being swayed. And that's part of the theater and the histrionics of the event.

[00:03:56] I tend to never do debates like that even if I'm in something that is built as a debate. At least on my side, I am open to changing my mind, except for the fact that I'm often debating on a topic where the bar is set so high that, that's just vanishingly unlikely that I'm going to change my mind. If I'm debating a fundamentalist Christian, the likelihood that that person in the context of our debate is going to convince me to convert to Christianity. And you recognize Jesus as my savior in that moment. You know, it's within the realm of possibility, but it's so minuscule that I never really have to consider it.

[00:04:36] But on any peripheral points that may come up, even in the context of that kind of truly polarized debate, I don't want to be wrong for a moment longer than I need to be. My view of saving base in those moments is that to attempt to save base by pretending that you are right when you are obviously wrong is to lose face twice over. What you want to be is someone who sees the merits of the other person's argument or the factual inaccuracies on one's own side as quickly as possible and gets off that shaky ground.

[00:05:12] So the people who refuse to admit they're wrong, even when the audience can see it just look terrible. That's something that I'm increasingly sensitive to. Paradoxically, it's hard to be truly sensitive to that in oneself. You see the evidence of that all around you, where people are just frustratingly, boorishly, comically wrong in public and refuse to admit it in real time under pressure because they imagine that their stubbornness is somehow a virtue and as anything, but it's just this awful confession of intellectual dishonesty. So, if you can sort of triangulate on yourself and see yourself from the point of view of an audience or know what it's like to have been a member of that audience on other occasions, you see that you actually don't want to be stubborn and slow to notice that you just made a mistake or that there was an inconsistency in what you said, or that you are mistaken in any other way.

[00:06:07] Jordan Harbinger: You receive a lot of criticism. I've seen it in the research of you. When I was doing it before the show, I've seen it in just people even reacting to me saying, "Hey, I'm having Sam Harris on. Have you ever heard of that guy?" And it's just like, not printable. Some people were really stoked. The majority, if it makes you feel any better, were very excited but a lot of people were very aggressive. The stuff I've seen on the web as well, very, very aggressive. A lot of it, quite frankly, is heinous. How do you deal with that so it doesn't affect your work and your personal life? Or at least you minimize those effects. If you can't make it not affect you at all, I would imagine that's very difficult.

[00:06:41] Sam Harris: I can't say that I'm an expert at this. I've had a lot of practice, but I can't say that I'm especially good at stewarding my attention in a way that is truly wise here and avoids most of the unnecessary hassles. I think what I do for the part is ignore it until something impinges upon me that I just seem unignorable and then I react to it and I think I'm getting smarter in how I react and the battles I picked to fight.

[00:07:10] I mean the most frustrating aspect of this is not that people criticize me for views that I actually hold. And that those criticisms are in some sense, wounding or destabilizing or cause me to doubt myself or, I mean, there's great to be criticized for a view you actually hold and to see some merit in that criticism. I find that incredibly interesting that that's what conversations are for. Certainly when you're talking about issues of consequence, the vast majority of the criticisms I get, certainly the most scathing ones are based on, in many cases, deliberate misrepresentations of what I believe or what I've written or what I've said publicly, or just frank misunderstandings of what my views are.

[00:07:54] So I find that really frustrating because there's not a comment thread on earth at this moment, dealing with anything I've written or said, which isn't riddled with people confidently deriding me for views that I don't hold. And this is in large measure the result of a very calculated campaign to lie about my views. I mean, they're public people who absolutely know they're misrepresenting me and continue to do it because it's effective and that is just an incredibly cynical and depressing feature of our public conversation. But people do this, and they're not just Internet trolls, these are people who have significant platforms online and people who even get described without scare quotes as being journalists.

[00:08:41] It's a problem that people notice this and notice that it's just not worth commenting on certain polarizing issues, because it's just too much of a hassle. It's too much of a hassle to take other people's feet out of your mouth again and again, and try to get yourself understood. You know, in certain cases it's just impossible. I have had to acknowledge that it is a hopeless battle on the one hand. I will never get myself to a position where I'm free of people openly misunderstanding me and either not caring or having that be their goal to spread misunderstanding of my views. And I'm just getting less and less frustrated now because I just had to dial down the frustration on my side. There is no remedy apart from trying to make sense in the next moment and moving forward.

[00:09:29] There is the aspect of what I would call trolling in the broadest sense. It's kind of a misuse of the original meaning of what it's to be a troll on the Internet, but it's not really about honestly, even spreading your views. You're basically kind of vandal, you know, vandalizing people's reputations, and it's fun. So there's a lot of that, but then there are people who believe they're on the right side of some important argument. They believe it could be extremely to the left or extremely to the right politically, but usually they're not moderate of any kind, because moderation is almost by definition, the position of being open to arguments to your left and arguments to your right and open to modifying your views.

[00:10:15] But if you're extremely ideological, politically, and you feel you're on the right side of some important issue, let's say it's how minorities are treated or affirmative action or black lives matter, something that's in the news now, you find people who are so convinced of the rightness of their view, that they don't care that they're being dishonest in the promulgation of their views. As long as they can score points that get on the board or they can land blows against their ideological opponents, basically, anything is fair. And they know that people's attention span is so trimmed down now, by just how much we're paying attention to.

[00:10:57] I mean, the social media is kind of the ultimate example of this, where nothing lasts. You know, you can just make your point and move on and never have to acknowledge that you have been shown to be in error. That the article you just forwarded about somebody was debunked and the author admitted his mistakes and you forwarded it. You're not going to go back to your Twitter feed and clean up that mess and that mess stands for all time now. The person who feels more scrupulous about all that and wants to apologize for his errors and has an audience that cares that he's honest and consistent and is keeping score to some degree, that person is really at a disadvantage. And, you know, there are people who have curated their audiences in such a way or assembled their audiences in such a way based on how they operate in public, where they're in an echo chamber. And some of these echo chambers are vast.

[00:11:51] There are many people playing this game and it's obvious in politics, but it's happening more and more in journalism where journalism just becomes a political act of expressing highly polarizing and ultimately dishonest, or at least knowingly incomplete opinions about the world and just scoring more points for your team. And I find this increasingly scary. That everything is taking on this character of politics where it's like your epistemology becomes political first. You know, people believe in climate change or not based on their politics. People believe in vaccinating their children or not based on their politics. And they think that science and reason generally can be beholden to feeling and what you want to be true in a way that it can't.

[00:12:43] If you are trimming your worldview down based on what makes you feel good, what your team believes, and you're a member of that team really just by of birth, you know, it's your religion or your nation or your family's politics that you inherited, you're not actually in touch with reality. You're not doing anything that would reliably put you in touch with reality or correct mistakes. And so it's scary because we have public opinion being swayed, even on fundamental points that are nothing to do with politics. You know, the age of the universe, there are some vast numbers of Americans in polls that has ranged from, you know, 30 percent to 45 percent, depending on the poll. Believe the universe is 6,000 years old. That is not an opinion that any sane or educated person should be able to hold at this moment. And yet, they think they're actually dealing with facts.

[00:13:38] And again, in this case, you know, there are religious reasons, but it all has this character of thinking that your reasoning can and should be constrained by where you want to arrive on its basis. It's like you have the conclusion you want in hand. You don't want there to be global warming, right? You don't want to believe that there's anything you have to take into account of economically that is affecting the health of the planet. You're just going to pick and choose your opinions to arrive at that conclusion. It's a starkly delusional way of operating yet, it's just more and more common.

[00:14:13] Jordan Harbinger: And we see this a lot with more and more junk science, things like, "Chocolate is now good for you if you're pregnant." "Oh, global warming is not a thing according to this study, funded by people who make plastic," or whatever. I even saw a quote from Al Roker or something like that from The Today Show. And he is like, "What you need to do now is just pick the study that you agree with most." And it's like, well, no, that's not how science is supposed to work.

[00:14:34] Sam Harris: Yeah. I mean, we do that and kind of helplessly and we are confronted with this, depending on the area of science. You're talking about what can be a real bewildering diversity of opinion. When you're talking about what to eat, this is the most humbling, really scandal of science at this moment, that the fact that there's any uncertainty at all about what constitutes a healthy diet for people at this point, it's just crazy. But, you know, there seems to be some significant seems grounds for debate about whether is saturated fat is bad for you, for instance. And so it's just a measure, not of the fact that nothing is true or that there's no difference between good and bad diets, but that it's hard to do science and there are many vested interests contaminating the conversation.

[00:15:24] In certain areas of science, there's both scientific fraud and just confirmation bias and publication bias where people throw away studies that didn't work according to what they wanted to have happened. And they then published a few studies that did work. And so you have what is called a file draw effect where you're only pulling out positive results and hiding all the negative results. And this happens in the pharmaceutical industry, but the remedy for that, and as depressing as all that looks and as disparaging of science, as that can seem to be, the remedy for all of that is just more science and better science. It's not some other mode of thinking that is going to deliver us the facts.

[00:16:02] I think you should be basically skeptical and skeptical requires a little calibration. It's not skeptical in the sense, that you're a jerk, but there's a price to paid for changing my worldview and that price is good evidence and good arguments. That's the coin of the realm. You know, if you come to me with good evidence and good arguments, I'm going to be swayed to the degree that you deliver the goods. And I should want to be swayed. I shouldn't want there to be any friction in the system. And if there's naturally going to be some friction, depending on what you're talking about.

[00:16:39] So you're going to try to convince me that you've built a perpetual motion machine, right? Well, then the bar is set very high because I know all of the reasons why that hasn't worked out in the past. I know that tends to select for people who are crazy and there are very good physical reasons to think that no one who claims to have come up with a perpetual motion machine is actually right about what they're claiming. So people have limited time and attention and limited patience. So it's not like you have to give every crank a full hearing or the same hearing you would give a Nobel laureate in physics who says he's found something interesting at the margins of his actual expertise, but generally speaking, you should be really just hungry to confront your own mistakes and to be shown where your beliefs about the world are, in fact, not true.

[00:17:37] And what you discover in people is a very strange bias in the other direction, which is they have what they believe. They spend a lot of time and a lot of effort not wanting to change their beliefs under pressure, especially in public and they spend very little time worrying about the possibility that they actually might be mistaken and might be paying a price for those mistakes, even now. In the sense that their beliefs are not equipping them to get what they want out of life and that other people can see that they're mistaken and that their reputations, that they think they're safeguarding by persisting to hold onto these beliefs and not change them, even in the face of good evidence and good arguments. That this persistence is actually making them look both stupid and stubborn.

[00:18:28] It's amazing that there is this mismatch between what we think makes us look good, and what we effortlessly recognize looks bad on other people. If there was a piece of clothing you could wear, which you thought looked great on yourself, but the moment you put it on another person, you could recognize that this is like the least flattering thing a person could possibly wear. There are many pieces of clothing like that. We just don't recognize them.

[00:18:53] So if you have one example that comes to mind is namedropping. Namedropping, it almost never looked good. Obviously, there are people who are famous and are around famous people all the time and they can't help but name drop. They're not even namedropping because they're themselves famous. And they're just talking about their friends on some level. You sort of know it when you see it. The people who are namedropping, you recognize that it doesn't look good. It's almost never having the effect. They're hoping it will have and yet the temptation to do it, oneself is often irresistible and the person who's doing it never notices that they are now the person who looks like a namedropper. They never notice there's something unseemly about what they're doing.

[00:19:36] And there's so much of life is like this, where people are functioning with a basic lack of self-awareness. And yet it's an awareness that they immediately have of others. So because of bringing those two lenses into some kind of register is certainly helpful. You can be aware of the fact that you are transparent to others in ways that you are not transparent to yourself and despite your best efforts, this is going to be the case. So, you know you can be unaware of your emotions in a moment, in a conversation. You can be unaware, for instance, that you're angry or that you're getting angry, but it can be absolutely obvious to other people. And the look on your face can be angry. Your tone of voice can be angry. And they're in that moment it's true to say more aware of your mental states than you are. If someone can say it to you at that moment, you know, "Why are you getting so angry?" And you'll deny it. You'll say, "I'm not angry," because like a basic lack of self-awareness is almost a given.

[00:20:38] I mean, there are ways to correct for this. You can learn to meditate, you can go into therapy. You can think in these terms more and more, and try to triangulate on yourself and be better at playing this part of the video game, that is your life. But still, there is just this basic fact that we are not perfectly equipped to know ourselves totally in each moment. And yet part of ourselves is bleeding into the world and is being known by others. You have to understand and be mindful of, to the degree that you can actually do less damage to yourself and other people and to your reputation. And this is sort of humility that can creep in here that is, I think, very healthy to have.

[00:21:23] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Sam Harris. We'll be right back.

[00:21:28] This episode is sponsored in part by Thuma. We recently replaced our cheap old bed frame. I mean, I'm like, okay, it's a bed frame. It doesn't really matter, right? Who cares? It's the bottom. It's not like that's the part I'm sleeping on. We have a really awesome mattress, but we just skimped on the bed frame and we regret it because, of course, it felt flimsy and kind of looked gross. So we upgraded to The Bed by Thuma, which is sturdy. It's solid. It's handcrafted from eco-friendly, high-quality, upcycled wood, modern minimalist design. It features Japanese joinery. So there's no tools, there's no screws. It's very kind of cool and fancy. Jen assembled it all by herself, which is better because I actually subtract from the process of assembling furniture and also yell and scream the whole time. It's actually backed by a lifetime warranty, which is good. I always get confused though, is that my life or the life of the bed? Along with the bed, Thuma offers other bedroom essentials like the nightstand, the side table and the tray. They really get creative with the naming. Plus it's great that Thuma plants a tree for every bed and nightstand sold.

[00:22:24] Jen Harbinger: Create that feeling of checking into your favorite boutique hotel suite, but at home with The Bed by Thuma. And now go to thuma.co/jordan and use the code JORDAN to receive a $25 credit toward your purchase of The Bed. Plus free shipping in the continental US. That's T-H-U-M-A.co/jordan and enter JORDAN at checkout for a $25 credit, thuma.co/jordan and enter code JORDAN.

[00:22:51] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Better Help online therapy. Here's something to ponder. Many of us will work out to stay physically fit. I just started a couple of years. But have you invested in your mental health as well? Because it's just as, if not even more important, in my opinion, it's actually more. I mean, sanity is priceless, right? A ton of you used to ask for advice on how to find a good therapist. With Better Help online therapy, you don't have to worry about finding the right therapist. You get matched with a licensed professional therapist in under 48 hours. If you don't jive, find someone else, no additional charge, you can chat with your therapist from the comfort of your own home. Easily schedule a weekly video, chat, text, phone calls. Many of you've actually written in and told me how Better Help has changed your life, your relationships, maybe your relationship with your job, depending on whether or not you're partnered up. A lot of you've also said that it's helped you stick with therapy the longest, which is awesome to hear. At the very least, you might feel better just having expressed yourself. You know, you can always sort of vent into the phone and there's not a whole lot of repercussions, unlike when you do it with your parents or your cousin or your sister. Plus it's much more affordable than in-person therapy. Check it out. They've got thousands of positive reviews online and for the Better Help app as well.

[00:23:55] Jen Harbinger: And our listeners get 10 percent off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan. That's better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan.

[00:24:03] Jordan Harbinger: If you're wondering how we manage to book all the great authors, thinkers, and creators here on the show every week, it is because of my network. And I'm teaching you how to build your network for free over at jordanharbinger.com/course. I know this is why people say, "Oh, you sound like a salesman." This is a free course. I don't want your credit card. I don't care about any of that. This course is about improving your networking and your connection skills and inspiring others to develop a personal and professional relationship with you. It'll make you a better networker, a better connector, and most importantly, a better thinker. That's all for free at jordanharbinger.com/course. And by the way, most of the guests you hear on the show, they subscribe and contribute to the course. So come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong.

[00:24:43] Now back to Sam Harris.

[00:24:47] You're a scientist, but most of your work, at least as far as I've seen, seems to be philosophy, at least recently. Why did you take a road through science to get to philosophy? Do you consider yourself more scientist or more philosopher? And does that distinction even matter?

[00:25:03] Sam Harris: Yeah, that's a good question. It doesn't matter to me at all. I've learned that it matters to other people and it shouldn't. I mean, I have an argument about why it shouldn't matter but it does. And so in the generic case, I call myself a neuroscientist, you know, an author and a neuroscientist because my PhD is in neuroscience, but my interest in the brain has always been philosophical. And I went into neuroscience very much as a philosopher. And I was thinking like a philosopher. I was reading philosophy. I had thought that I was going to do a PhD in philosophy. And then at the last minute decided to switch to neuroscience. And I did that because I wanted to know more about the brain.

[00:25:42] And my interest in philosophy has been focused on the nature of the mind and questions about what consciousness is and just all the questions of higher cognition and human subjectivity that are really easily talked about in philosophy and even most talked about in philosophy, but are more and more tied down to the facts as we understand them in a neuroscience lab.

[00:26:06] So, I mean, if you want to understand the mind and you want to understand people, in general, ultimately you have to understand the brain. We were really at the beginning of that effort. And I wanted to be as conversant as I could be with all of that. And so I went into neuroscience to do that. And I still do some proper neuroscientific research but mostly what I do is I read and I write and speak. And so I operate much more like a philosopher, but academic philosophers, you know, those who like my philosophy don't care. But those who don't would point to the fact that I don't have a PhD in philosophy. And that would disqualify me in their eyes from claiming to be a philosopher. But, you know, I think you are what you do. There are neuroscientists whose degrees are in psychology or linguistics or even philosophy. There are physicists who are top-flight physicists who do not have PhDs in anything.

[00:27:04] Jordan Harbinger: I don't think Aristotle had a PhD in philosophy either.

[00:27:07] Sam Harris: Right. And so if you go back far enough then you know no one had a PhD in anything. And credentials don't matter at all, unless you are making mistakes and people need to figure out why. If you're functioning appropriately in an area of discourse, you're saying smart things that are well justified and that people adequate to that conversation recognized to be smart and justified, and people want to hear the next sentence out of your mouth because the last one was a good one, and you show up at the conferences or you write books or papers, and all of that is working. If you can play the language game, then all that matters is that you're playing it at whatever level you're playing it.

[00:27:44] But if you're failing, you know if you're playing a game of tennis and you keep hitting the ball into the net or out the stadium, well then at a certain point, people are going to ask, "Well, why can't this person get the ball in bounds ever?" Well, it's because he never learned to play tennis, right? So the explanation may be, well, this person is pretending to be a neuroscientist or he is pretending to be a philosopher, but the reason why he's not making any sense is that he's not actually educated in any of those fields. Well, fine. But if you are making sense, that's all that matters.

[00:28:13] And I think the other point here really is that there is no real boundary between certain areas of philosophy and their contiguous areas of science. What kinds of questions are you tending to ask and how you would go about answering them in the near term? If there's an experiment you can run, well, then you're talking science. If there's no experiment, you can run necessarily, or what you're saying would just affect the interpretation of experiments, but not actually change the experiments that you would do, well, then you're talking philosophy. I think we move rather seamlessly and unconsciously back and forth between these two domains.

[00:28:50] I don't think you have to have your worldview defined by the buildings as they are arrayed on a university campus. And that's what seems to happen. And people are very concerned about whether something's philosophy or science or which part of science are we talking — is this physics or is this chemistry? Well, it's both or one or the other, depending on your matter of emphasis at that moment or the tools you would use to run an experiment.

[00:29:14] Jordan Harbinger: Well, getting back to your work, some of your more controversial stuff, you'd mentioned, you don't translate your work into Arabic because you don't want to have kind of a Salman Rushdie event where a translator is murdered because of a fatwa by some crazy Jihadist, et cetera. Would you be open in theory, an anonymous translation posted for free online, just to get the work out there?

[00:29:36] Sam Harris: Yeah. And I think that may have happened or if it hasn't happened, it probably is happening. And it's not that I have a hard and fast rule that I just will not permit anyone to translate my stuff into Arabic or do any of the other relevant languages but the times I've been asked and declined, it's forced me to think about consequences. And for me to be uncertain, whether or not the person who is offering to do this has thought about them as fully as he or she should. And for those who know, Salman Rushdie's book, The Satanic Verses, when it was translated and published, and it wasn't just in Muslim majority countries, one of his Japanese translators, if I'm not mistaken, was attacked or even killed. But anyway, there was some number of casualties around the translation and foreign publication of his book. I'm aware of taking risks in what I published, particularly on the topic of Islam, but I'm reluctant to have people absorb those risks for me without not really having thought it through.

[00:30:37] Jordan Harbinger: Do you ever fear for your own safety? I mean, a lot of your critics are absolutely insane and have actually made good on threats to murder other people who do and say similar things that you've said and done.

[00:30:47] Sam Harris: Yeah. Well, I take security very seriously and it's something I think about and plan for and train for, and I take it more seriously than I think many of the people who are doing similar work, but I also recognize that I don't have the same risk as some of my friends and colleagues. You know, I have friends like Ayaan Hirsi Ali or Maajid Nawaz, who I wrote this last book on Islam with, Islam and the Future of Tolerance, who are taking much more significant risks just by dint of the underlying theology to be a former Muslim to now be in apostate as Ayaan is. He used to be running a much greater risk than just being an infidel like me, who's disparaging all religion. You know, to be a Muslim reformer as Maajid is, and to be an apostate from the point of view of more doctrinaire and maniacal people, their security concerns are much higher than mine. But yeah, I don't take it lightly at all. And there are things I wouldn't do. There are places I wouldn't go to speak because of, I would perceive it, you know, rightly or wrongly as being a much greater risk than is warranted.

[00:31:54] Jordan Harbinger: I think that makes perfect sense. It just seems like you would've put real thought into, "Should I do this or should I not?" Whereas a lot of people just say, "Sure, spread the word far and wide," and then they kind of turn back and keep smoking their pipe or whatever and reading the newspaper. You probably have put more thought into it than that, especially given Salman's experience as well.

[00:32:12] Sam Harris: Yeah, yeah. There, there's also just the fact that you can't always anticipate what's going actually bring the heightened risk to your door. I mean, there are two kinds of risks that I deal with. There's the ideological risk, the jihadist who doesn't agree with, or the Christian fundamentalist, white supremacist, who doesn't agree with me. Then there's just the crazy person who thinks I have said something that got into his head or destabilized his life, or has meaning that only he can see and now has to persuade me of. That's a very distinct, and in some cases, even more, plausible risk. I'm always surprised at the things that provoke very weird communications.

[00:32:53] And so I wrote a book about free will, arguing that it's an illusion, and I was amazed at how agitated some of the response was to that. I mean, there are people who really felt like they kind of lost their minds, reading my book. And this was obviously not at all my intention. At one point, I was giving public talks when I released that book. I think I said at the beginning of a few of them that, "You know, listen, if what I'm saying over the next hour seems to be affecting you in a way that it seems psychologically unhelpful, please leave the room. Go get a drink. You can come back the Q&A," or whatever, but it's like, there's some people who are not up to thinking about certain things.

[00:33:35] And if you're one of them in this case, you know, recognize it early, and get out the room. It was something that I'd never imagined having to say, but my email box convinced me that I had to because I was getting totally anguished emails from people who had really been quite destabilized by my argument about free will in a way that I really couldn't understand from a first-person side, but just had to accept as being honest and, you know, worth taking into account.

[00:34:02] Jordan Harbinger: I'd love to talk more about lying. This book I read entitled lying is fascinating, especially the basic premise, which reeled me in right away is that we often behave in ways that are guaranteed to make us unhappy. And lying itself is so common. People do it without even thinking. We don't even know what life would be like without it. And some of the analogies are quite brilliant. We wouldn't want a car that told us we don't need gas when we really do, just because we're too lazy to stop. So why would we want that in our lives? And yet this is what most people seem to be doing.

[00:34:35] Sam Harris: Yeah. Well, where it gets controversial is on topic of white lies. So most people acknowledge that there is a problem or at least a potential problem with lying in general, where you're the head of a company and you're lying about your financials. You're engaged in a fraud. Or you're Lance Armstrong and you're taking steroids and you having press conferences and lying about it and lying about your teammates and, you know, suing them to shut them up when they tell the world that you are lying. And so it's like all of that seems pathological and most people recognize that's worth avoiding if you can at all help it. But they nevertheless reserve the right to lie on all these other occasions where they think it's actually a good thing to do and a compassionate thing to do, and that is actually improving their relationships rather than undermining them. They call these white lies.

[00:35:29] So much of the book, as you know, is purposed for arguing against this very notion of white lies. I think if you look closely at the circumstances where you think you are doing yourself or anyone else favor by misleading another person about what you actually believed to be true, you're not. And you can discover that what you're doing is quite obviously motivated by interpersonal fear with that person, and sometimes ramifying that fear and allowing your relationship to conform whenever you're found out you're diminishing the trust in the relationship, the trust that the other person could possibly have in you even if they were consoled by your white lie when you told it.

[00:36:14] One of my favorite examples in the book, I released that book as an ebook first, it was just a very short part of the book, but initially it was just a PDF that I released. And then I got reader feedback. I had readers tell me their stories about lies that had misfired for them and the price they had paid for lying or the lies of others in their lives. And one story that came in, which I used in the subsequent addition of the book was of two women who were out to lunch. And one said to the other, brought up a third friend and one said, "Oh yeah, I'm supposed to see her tonight, but I just can't do it. I'm so busy. I don't want to go out. I'm going to call her and just tell her I can't go out tonight."

[00:36:53] So in the presence of her friend, she gets on her phone calls this third person and gets her voicemail and just lies about why she can't have dinner that night. She says something about her kids being sick or whatever in the presence of this other friend. And so now, this story was delivered to me by this friend who just watched her friend lie with just perfect alacrity to a friend, kind of the same level and recognized in that moment that it just subtly but rather fatally diminished her trust in her friend. I mean, she just wondered immediately. She couldn't help but wonder how often she had been on the receiving end of that kind of treatment. What was so insidious about this is that it was not the kind of lie, nor was it the kind of friendship that required that she say anything. So she never communicated that she perceived as be an ethical problem or this had harmed their relationship. And so the person who was lying never knew that she had just sort of lost a friend to some degree. I mean, all of this is just so corrosive and so uninspected by most people. And so that's where the book focuses.

[00:38:03] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. The book is fascinating and that it explains how lying damages trust, how it never needs to be done. Light deception versus lying, I mean, you don't have to tell, "Hey, how you doing?" "Well, I've got a little bit of bowel dysfunction today. It's going like this." You can sort of separate that between why we can't make your birthday party or why we can't hang out. It's fascinating that you also get into the idea of which I think marketers and online personalities do a lot and now, of course, the layman through social media, we deliberately allow others to draw erroneous conclusions all the time. And you've even separated the act of commission versus act of omission and how one is punished more than the other. I would love to talk about things like candor and why candor doesn't necessarily equal truth in measuring truthfulness. That's of almost impossible to do this without a lot of deep thought, which you have mostly done.

[00:38:55] Sam Harris: So the commitment to telling the truth, it's definitely not the commitment to being totally uncensored and lacking in all tact. It's not like you need to become a Tourette's patient and just blurted out whatever's on your mind. It's not to say that that is actually the phenomenology of Tourette's syndrome, but you know, that's the cartoon version of it. But it's a commitment to saying what's true and useful. The filter is true and useful. And there are certain circumstances where you, I think, are wise to worry.

[00:39:23] First of all, there is no whole truth. You can't say everything you think about anything. You'd be there forever, right? So you're always picking and choosing things to say. And there are circumstances where I would admit that a slightly more paternalistic view of the person you're talking about is relevant. So that if you're talking to a child, if your seven-year-old asked you, "What is ISIS?" You don't have to immediately start telling her about all the decapitations happening in the Middle East. There's a reason to edit the truth and it doesn't require any lying. It just requires that you see that there's certain blanks on the map that are not appropriate to fill in for a seven-year-old. And there are grownups who occasionally have to be treated like children but we should recognize that.

[00:40:09] That's in fact what we're doing if you think someone really can't handle the truth about their life. You think this person's going to commit suicide if you tell him that you know that his wife is cheating on him or that you didn't like his novel or something. Well, then you have to acknowledge that you're dealing with someone who you think rightly or wrongly is not a fully competent interlocutor. This is somebody who you are protecting from himself. Those are really unique circumstances when you're talking about adults. And far more often, we're just uncomfortable communicating what is true because we don't think it makes us look very good. It puts us in an awkward situation and so we're protecting ourselves or imagine we're protecting ourselves.

[00:40:51] We're not giving the other people in many cases, an honest look at what our situation actually is and what our relationship actually is and what they can expect from us in the future and the kinds of friendships we want to have with them. There's a mismatch between their expectation and what, in fact, you intend to do the next time you're in a room with them. So if someone sending you emails about wanting to get together for lunch, and you just simply don't want to have lunch with this person, and you don't want this kind of relationship with this person, and you don't even like this person and they don't know it, right? I would grant you that there are more and less tactful, more and less polite ways to resolve that situation. But the thing that most people do is they just punt. They tell a white lie. They say, "Oh, I'm just really busy this week. Sorry, I just can't do it." And then, you know, you get an email from that person next week. At a certain point, you either have to confront this or you just keep making up more elaborate lies, and hope they get the point.

[00:41:50] If you want to live your life with integrity, just look at what integrity means. Integrity is a closeness of fit between what you will say to someone's space and what you will say about them when they leave the room. If there's a real distance there, one, you're not a good friend. That person is in fact, your friend, but also you're a scary person for others to be around. We've all be this person. We've occupied each one of these roles. Do you know what it's like when someone leaves the room and the people who are left immediately start talking about them? When you see someone say something that, you know, there's no way they would say that in the presence of the person who has left, you know that this person is advertising to you something about themselves, I think diminishes your trust of them. What are they saying about you behind your back?

[00:42:39] And yet, the person who's dishing now about the other person is rarely aware that this is in fact what's happening. They're rarely aware that they are advertising their capacity to stab others in the back. I mean, there are many people who I will say terrible things about because I think terrible things about them, but I will also say these things to their face. I've worked very hard to do that. I can't say that honestly there's no difference between how I would speak about someone to their face and behind their back, but there's much less difference than there ever has been in my life. And certainly, there's much less than I see in the lives of others. And there's an immense power to that. You can be overheard by anyone and be unembarrassed.

[00:43:24] And it also forces you to confront your mind as it actually is. I mean, if you're a petty judgmental self-serving asshole, forcing yourself to be honest with other people, holds a mirror up to that side of your life very, very quickly. If the truth about why you don't want to go out with someone, right, is that you only want to date people who are 15 years younger than yourself and look like they're fitness models, well, that's a truth you have to confront if you don't give yourself an out about lying. If you can't have recourse to, "Well, sorry. I just don't like being in a relationship now," whatever the lie is, it's something that you actually do have yourself, whereas the liar, in fact, never even notice it or never see its implications.

[00:44:07] The moment we acquired the facility to represent the world in language and express our beliefs, acquire new ones, and modify the beliefs of others in conversation, I think, we very quickly learn to lie and notice that in certain circumstances there was a real benefit to lying. But one place where I do reserve the right to lie in any circumstance where I would otherwise also act in a way that would seem unethical in the way where I would use violence, like in a self-defense situation. If you're in a situation where you could someone in the face and call it self-defense, well, obviously you could also lie to that person as a lesser act of violence. So I think we've always seen the utility of manipulating one another with lies. And then there's just all of these cultural artifices that we've acquired since which depending on what culture you're in, have dignified certain kinds of lies necessary or appropriate social relations.

[00:45:06] So you're being polite when you're telling that particular kind of lie, certain ones of these are still hard to get around and I'm not especially dogmatic about this. You brought up one when you raised this topic about just the nature of greeting somebody when they say to you, "How are you doing?" And you say, "Oh, I'm great. Fine. How are you?" You realize that the question isn't what it seems to be. It's not that they really want to know about the state of your bowels or whether you slept last night or how your marriage is going. They're just saying hi. This is just in your language. This is how you say hi, say, how's it going? In another relationship, it would be a lie to say, you're fine if, in fact, you know you're miserable and you're now talking to your wife or someone very close to you who actually does want to know day in and day out of how your life is going.

[00:45:53] There are things that can seem like lies on the surface, which in fact aren't lies because what's really being asked is, people are asking you to perform a kind of ritual, but for the most part, I think it's just a constant and differs from culture to culture. I don't know, there's actually gotten worse in any way in our lifetime. I think one thing that's gotten better is it's harder to successfully lie if you're at all a public person because nothing disappears on the Internet. Everyone is just trailing more or less everything they've ever said or written. And now for all time that this is going to be the case. You can just look to see what the person said on that occasion and some great examples of people lying and then being caught or lying about what others have done, and then being caught. There's a video record of the very event they're talking about. I think that's very useful. I think the more sensitized people get to the prospect of being caught in their lies that will make for a better society just across the board.

[00:46:55] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Sam Harris. We'll be right back.

[00:46:59] This episode is sponsored in part by Squarespace. If you don't already have a website, well, you probably should. Having a personal site will set you apart from the sea of resumes while still remaining professional. It's a great strategy to showcase your work even if you don't have a business. Sure, having a business website will build credibility, but even if you don't, it's great to have your resume on a website. It just has your personal brand cemented a little bit better than a regular social media profile or set of profiles. And it's never been easier or more affordable to create one. Service providers like Squarespace, they embody this ease of use better than any. You don't have to know how to code. You. Don't have to fidget around with spacing and all that stuff. With Squarespace, you just pick a template, a design theme. You customize by integrating your own images, copy and social media icons. Squarespace has all the tools you need to get your personal site or online business off the ground. You can even generate revenue through gated members-only content, manage members, send email communications, leverage audience insights, all-in-one, easy-to-use platform. You can also add online booking and scheduling, which is super helpful especially if you're a professional, you're taking meetings. You can connect your social media accounts to your website, of course, create email campaigns, all with Squarespace tools. There's not a billion things you get plug in, and these examples don't even scratch the surface of what you can get done on Squarespace.

[00:48:12] Jen Harbinger: Give it a try for free at squarespace.com/jordan. Go to squarespace.com/jordan and use code JORDAN to save 10 percent off your first purchase of a website or domain.

[00:48:23] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Progressive insurance. Most of you listening right now are probably multitasking. So while you're listening to me talk, you're also driving, cleaning, exercising, maybe doing a little grocery shopping, but if you're not in some kind of moving vehicle, there's something else you could be doing right now, getting an auto quote from Progressive insurance. It's easy and you can save money by doing it right from your phone. Drivers who save by switching to Progressive save over $700 on average and auto customers qualify for an average of seven discounts — discounts for having multiple vehicles on your policy, being a homeowner, and more. So just like your favorite podcast, Progressive will be with you 24/7, 365 days a year. So you're protected no matter what. Multitask right now, quote your car insurance at progressive.com to join the over 27 million drivers who trust Progressive.

[00:49:06] Jen Harbinger: Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. National Annual Average Insurance Savings by New Customer surveyed, who saved with Progressive between June 2020 and May 2021. Potential savings will vary. Discounts, not available in all states and situations.

[00:49:19] Jordan Harbinger: Thank you so much for listening to the show and for supporting our sponsors. A lot of you have been doing that, but you know, the rest of you should be doing that. Come on, now, if you're going to buy something, just go to the website at jordanharbinger.com/deals. All the discount codes, everything there is all in one place. You can also search for the sponsors using the search box on the website as well. The whole thing is searchable. It should come up with a sponsor right away. So if you're going to buy something, you want a mattress, got a little cutlery. You need some blankets, I don't know, whatever. Please consider supporting those who support this show.

[00:49:48] Now for the rest of my conversation with Sam Harris.

[00:49:53] I've read the book and I've done this before in years past. I monitor how often I tell things like white lies and I realize, "Wow, I do this a lot more than I think I do." And the reason is to make things easier for us in the short term, easier for me and them, frankly, in the short term, friends, family, et cetera. But once you stop, you start to see, "Oh, people might see me as brash," but in the end, they appreciate it. And like you said, it makes you almost scandal-proof because weakness comes in pretending to be somebody, especially if you're a public figure, that you are not, and it makes you the bad kind of vulnerable.

[00:50:24] And the honesty that you mentioned before can really force any dysfunction, any sort of thing that's wrong in your intimate life to come to the surface. The example in the book, if you're in an abusive relationship, if you won't lie to others and they ask how you got that bruise, or why you look terrible or things like that, I mean, it would cause you to come to grips with the situation very quickly, drugs, alcohol addiction, lying is really a key component of addiction that goes untreated. And if you have no recourse to lying about things, you can really unravel things early enough to maybe make the damage not so severe.

[00:51:00] Sam Harris: Yeah. Oh yeah. I've experienced that in many ways. And just to go back to something you just said though about making it easier for yourself and easier for the other person in the moment, it's worth lingering on just the conception of easier for the other person for a moment. Because it easier in the sense that you're telling them what they want to hear or telling them something more pleasant than is, in fact, what's true. But you might also be causing them to waste a tremendous amount of time or encouraging them to waste a tremendous amount of time where you could be helping them to get their life on track in a way that other people around them aren't.

[00:51:40] So the classic example for me is when someone asks you to give your opinion of their book or their screenplay, or, you know, something they've been working on. So let's say you read their book and you think it's terrible. Obviously, it'd be much more convenient for both of you if you read their book and you thought it was great, because then you could say it was great and then you feel good and they feel good and your friendship is intact, and there's no problem. But if a friend of yours comes to you with something that they spent a lot of time working on and you think it's terrible, if you're helping them by sparing them this momentary discomfort of you not supporting their rosiest conception of themselves, then yeah., I think you really need to look more closely at that. Because I've been on both sides of this, and I can tell you that the people who didn't give me honest feedback or just didn't have good critical feedback to give were far less helpful to me than the people who said, "Listen, you have to tear this thing down to the studs. This is awful. You're lucky only I saw this." Other people who aren't their friends are not going to spare them, their criticism.

[00:52:45] The way to think about it in these cases of creative work, what you're doing for your friend is this thing is not yet out in the world, right? It's a different circumstance when it's out in the world and there's nothing they can do about it. Then you're having a different conversation, which is arguably harder. But if you're still in a position to give them some help by giving them honest feedback, then you really should give that feedback. And you can always give it in a way that acknowledges that it's just your opinion. You know, you're not omniscient. You're not the ultimate arbiter of what is good in the world. But if you have an informed opinion and you have reason to think that other people are going to share your view of the things they're getting wrong, well, then you should really just be candid. And if the person you're dealing with is at all an adult and actually wants to be spared future embarrassment, well, then they're going to be grateful for your candor. And they're actually going to find the friends who just glad-handed them and sent them on their way totally useless.

[00:53:42] It's always interesting to look back on the praise one received for things that one now thinks were terrible. Imagine you've got two friends, you're doing something you really hope is going to be great, you show it to two friends. And the first friend tells you, "Oh, everything is wrong with this. And it's going to take you a lot of effort to make it right. But you got to get in there and do it because its present form, this thing is terrible. And you wind up agreeing with him, right? And you do the work and you make all those improvements. But you have this other friend who saw your first draft and said, "I think it's great," that person is far less valuable to you in that capacity. And it would be an irony if the person was simply lying to you, thinking he was going to spare you some discomfort.

[00:54:23] There are people who ask what you think. And they actually don't want to know, right? These people are functioning like children in a way. The one thing that happens once you become more and more committed to being honest is you train the people in your life. They know what to expect from you. I don't find people coming to me anymore who don't actually want to know what I think. And that's also very helpful. And then people return the favor. If you're someone who was really honest in criticizing what somebody was doing, and then you need criticism of your own work, well, then you can get it. You know, there are people who are locked and loaded and ready to return and kind. At a certain point, you're desperate for this because it's just, why would you want anything else? You're not going to be spared this feedback once you go public with your work.

[00:55:12] Jordan Harbinger: It goes back to what you're saying, when we lie to people, we treat them like children because it fails to prepare them for encounters with others, the public, for example, who will treat them like adults and won't be as kind to spare their feelings short term. And research shows even in our own intimate relationships that lies are correlated with less satisfying relationships so that short term, over long term, like you and I have both discovered firsthand and me especially more recently after having read the book, once you commit to telling the truth, you start to realize how rare it is. You start to realize that, "Wow, I only know a few people who will tell me the truth about their truth, about pretty much anything," and honest people's opinions become worth more because they're trusted. It is better to be trusted than merely liked because it's easy enough to get people to like you, it's hard to get people to trust you. One is certainly, in my opinion, more valuable than the other.

[00:56:05] Sam Harris: Oh, yeah. Trust is the most important thing here. And one thing that I'm happy about with respect to my own audience in large measure, the result of having written that book Lying, you know, I've gone on record as someone who just doesn't lie. And I now have a core audience of people who really are engaged with my work who have just the shortest views imaginable with respect to any perceived inconsistency or lack of intellectual honesty on my part. I've got the anti-Trump audience. The irony here is that I'm often accused of having a cult of followers who will just take my side in any argument, you know, who will just flame people on social media in ways that are not warranted.

[00:56:52] But what in fact, I have is many core readers and listeners to my podcast who just have zero tolerance for what they perceive as a contradiction or intellectual dishonesty on my side. I love that. It's a bit of a hassle because often these people are perceiving a contradiction where there isn't one, or I simply misspoke, or some glitch just gets magnified because everyone is just watching me, really keeping score in a very rigorous way. But I really do love it because what's being said to me again and again, under this guise is people really trust me. And that's the most important thing. And if I break that trust, you know, I'm screwed. I'm happy that I have kind of taken my conversation on this topic so far in that direction, that hypocrisy there will not be tolerated.

[00:57:43] Jordan Harbinger: What about relationships with friends, spouses, and even family that are essentially really, really difficult to maintain without lying? I think a lot of people have relationships like this, even if it's just, "You got to keep telling Angela she's pretty because they propping up her self-esteem. I've got to keep telling Jordan he looks good in those pants," or whatever. What do we do about those relationships? Do we sever ties or do we just start being honest right away and deal with the consequences?

[00:58:11] Sam Harris: I think you can move it in the direction of more and more honesty, however, incrementally and deal with the consequences. And certainly, if the relationship is important, it should be important to improve it in whatever way you can. I acknowledge that there are circumstances where this is just not practical basically. You know, you have one Thanksgiving dinner a year with these people and your job is just not to ruin it. You know, you're not going to change anybody. You're not going to perform an exorcism. That's going make your aunt or uncle a fundamentally different person.

[00:58:40] But in those cases, I think you can just be tactful. You can change the topic. You can just simply not comment on things that you might have a lot to say about. And so being political in that sense, and just being wise to avoid specific issues is not the same as lying, even keeping a secret is not the same as lying. If someone says to you, how much money do you have in your bank account, or asks you to divulge information that you actually don't want to divulge, the truth is you don't want to tell them. So you can say, "Listen, I don't want to tell you, I don't give that information out." So you can be perfectly honest and withhold certain things.

[00:59:17] You can also be honest and just not get into certain conversations with people where, you know, it's not going to go well. It's good to play with the uncomfortable edge of this a little bit, and be more honest than people might expect you to be. What's important in those circumstances and certainly in relationships that matter where you're actually trying to maintain a good relationship with this person, you're on the same team. This is not an adversarial form of honesty. You're trying to have a better relationship. There's a psychological cost that you are paying for having to conceal how you really feel about something in this person's presence. And you don't want to pay that cost any more because you want to have a better relationship with them. You know, you respect them too much, or you love them too much, or like this is intolerable, that this is so weird.

[01:00:06] That you can't talk about how you feel about X, Y, and Z with your mom or whoever it is because you're so busy sparing her feelings because she is such a brittle person that she has just endlessly advertised to you that if you say the wrong thing about X, Y, and Z, she's going to go berserk right? So you can either try to improve all that or you can treat this person as an adversary in some sense. I'm not saying adversaries don't exist, but then what you have to acknowledge is that you are in large measure, avoiding relationship with that person. They're the kind of person that is incapable of an honest relationship. And you can't cut all those people out of your life. I mean, certainly, you can't cut your mom out of your life or you shouldn't be eager to, you can decide who to spend time with. Obviously, you want to spend time with people who you don't have to do that with.

[01:00:56] Jordan Harbinger: Especially given the psychological cost of lying, having to then keep track of lies and other people's lies if we're complicit with their lies. You mentioned in the book as well, there's a psychological process where we actually devalue people that we lie to in order to rationalize our own behavior. Like they matter less subconsciously because we're willing to lie to them. Therefore, the reason we're willing to lie to them is because, well, they matter less. They're less important or they're less evolved or they're less salient in our own lives and that can be very toxic. The willingness to be honest about things we might otherwise conceal is a really strong foundation for great rapport and relationships with others. People bond very strongly on insecurities when shared almost like a superpower to be strong enough, to tell people the truth about yourself. The reactions that you get from other people who find this so refreshing and powerful can have ripple effects around you in your social and intimate circles.

[01:01:51] Sam Harris: Yeah. And that's another one of these blind spots that people think that being vulnerable is a position of weakness and it's unattractive. And so they conceal their vulnerabilities. It's like the opposite of the namedropping example I gave you. So from the inside, you don't like feeling vulnerable. You want to hide this about yourself, you don't want people to see it. So the last thing in the world you're going to do is tell a story where you have to reveal what a schmuck you are, as you say, once you get to the other side of that, where you see how much enjoyment you get from other people's exposing this about themselves. And you see in your whole careers are built on nothing more than a person's ability to expose their most vulnerable parts.

[01:02:36] You know, again, this can cross over into stick and become just performance, but, you know, obviously, you know, comedians and other beloved entertainers are often beloved precisely because they're just like performing a perpetual autopsy on their failures. And that's how they're succeeding in life and say it is kind of superpower to just have nothing that's going to embarrass you. Again, this is where integrity is worth meditating on for a moment. When there is no distance between who you are in private and who you are in public, there really is no capacity for embarrassment. If you're not concealing something about yourself that you're hoping others will not notice, you're not trying to foist any illusions on people about you, but you're simply just of peace and living your life, honestly, representing your views and willing to talk about anything, that's a kind of superpower. It's just so rare.

[01:03:35] Again, I certainly can't say I've perfectly achieved it. I know what the bull's eye looks like, and I know when I land in it, and I know when I land just outside it. And just as a matter of ethics and a matter of just personal growth, I think it's useful to become less and less comfortable with one's own duplicity, being two-faced and saying the thing to the person's face and having something very different to say when they leave the room. All of those dichotomies, ultimately, I think we should find them intolerable. There is a lot of strength that comes from that.

[01:04:08] Jordan Harbinger: What about lying on a cultural level? Like lies in public discourse, for example, which have led to ridiculous conspiracy theories and rampant distrust of authority. It seems now, and you mentioned this a little bit earlier, we can't even talk about serious things like climate change and going back to originally what we were mentioning nutrition, because we don't even trust the scientists and the experts now. It's almost the cultural phenomenon in which you just expect everybody's totally full of it.

[01:04:35] Sam Harris: Yeah. Well, part of that is just having the incentives misaligned, the conflicts of interest, and we know that this confounds people's ability to reason honestly. And we need a system that corrects for that and science taken in its totality does correct for vested interests and wishful thinking and even fraud. The consequence of public lies, the consequence of government's lying and corporation's lying, and individual scientist's lying and getting away with it for some period of time, it's just enormous. It's incredibly toxic and this distrust of authority or not being able to figure out who the actual authorities are on any given topic, it's a real problem. There's a kind of nihilism that creeps into the public conversation on really consequential issues. That is, you know, if taken seriously, just a perfect impediment to getting anything of value happening in the world.

[01:05:35] People who think that's basically no such thing as truth or that it just doesn't matter what the truth is or you can make up any truth that you find consoling, the influence of conspiracy theory, thinking so much of the public on any given topic, it's very harmful. You know, paradoxically, the Internet has both enabled it and provided an antidote simultaneously. It's much easier to debunk lies given the Internet, but it's also much easier to go wall yourself off in an echo chamber that's filled with almost nothing but lies and just stay there and never have any other way of thinking impinge on you because you've basically just curated your ignorance and misunderstanding. You know, you have all the tools to do it.

[01:06:22] Jordan Harbinger: What are the most important goals of the human race right now?

[01:06:27] Sam Harris: Well, I think wellbeing is our main concern. And I mean, you can define that as elastically as you want. The concept can absorb every distinction between happiness and suffering that we can find and those that we've yet to even discover. This arrives in every way imaginable. I mean, so, you know, Zika virus, right? We've got a mosquito-borne virus that is causing women to give birth to microcephalic kids, right? You know, if there were God who was dishing this out to us, he would be an invisible psychopath who we would be right to fear, but certainly wouldn't want to love, right? This is the world we live in where this kind of thing happens. How can we deal with this? Well, prior to science, there was nothing to do.

[01:07:15] And now with science, there might very well be something to do in pretty short order. We can have a vaccine against Zika. We can genetically engineer mosquitoes that can't pass it on, or we may in fact be able to engineer mosquitoes out of existence. So that's just one question of a million where you just see clear thinking about the nature of the world, an honest conversation, being really our only tool to solve a crushingly tragic problem that just comes out of nowhere. Who could imagine that mosquitoes could do something that will cause a woman to now have a child who will die early? And that is going to be her experience of motherhood, and this child's experience of life, totally defined by a process that generations prior to us, and not only didn't understand but were in no position to possibly understand. Most of human history has been a time of no progress at all, right? Where we're just apes trying to eke out a less miserable existence.

[01:08:23] I mean, really on the cusp of either a problem has a solution or it doesn't. If we could just cease to needlessly make ourselves miserable by fighting unnecessary wars or having a significant subset of humanity devote their lives to just divisive delusions, we could just get down to the business of maximizing human flourishing. And that I think is really what we should be doing all day long and their creativity and love and wisdom and good conversations is all we need.

[01:08:57] Jordan Harbinger: You're about to hear a preview of The Jordan Harbinger Show with a retired chef that somehow infiltrated the illicit North Korean arms trade.

[01:09:04] Ulrich Larsen: There was a meeting where people can come and see how North Korea is the propaganda way. It was like free hours, praising Kim Il-sung by what he did for the country. When people ask me, how is it to go to North Korea? Well, it's quite difficult to describe because it's like your whole body is on overtime. You know you're being followed. And what do I say? And what do I do? How do I react to things?

[01:09:31] I'm going to the US to meet up with CIA agent. And I was like, "Wow." And I found out how an agent thinks. One of the most important things he taught me was to be a perfect mole or undercover is that you have to be 95 percent yourself and then five percent mole. The last five percent is the one who observes. And I was really good to networking with people without people actually know I was networking with them.

[01:09:59] Everything was recorded. So I just literally took the pants down on a whole regime, exposing their weapons program. It's a never-ending story.

[01:10:08] Jordan Harbinger: For more on how Ulrich "The Mole", a Danish chef and family man wound up working undercover in North Korea to expose its illicit arms trade, check out episode 527 of The Jordan Harbinger Show.