How high are the geopolitical and technological stakes in the international struggle for semiconductor supremacy? Chip War author Chris Miller chimes in!

What We Discuss with Chris Miller:

- Semiconductors, commonly known as semis or chips, are essential components in thousands of products such as computers, smartphones, appliances, gaming hardware, medical equipment, and military technology.

- How superconductors evolved to become so crucial to our modern infrastructure.

- The intricacies of semiconductor manufacturing — from their complex operation to the resources required to create them — mean the countries that can produce the most advanced chips have a strategic advantage on the world stage. Taiwan is currently the leader in this field.

- Why China, despite investing heavily in semiconductor technology, is always playing catch-up with the rapid pace of Western-influenced technological advancement — and what underhanded steps it might take to slow this pace to its advantage.

- What the recently passed CHIPS and Science Act will likely mean for semiconductor research and manufacturing jobs in the United States.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

On this episode, we’re joined by Chris Miller, author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology to find out. Here, we discuss how semiconductors became so crucial to nearly every aspect of technology we enjoy today, why making them is such a challenge, what’s keeping China from catching up to its competition (and what it might do to force a more level playing field), what the recently passed CHIPS and Science Act will likely mean for semiconductor research and manufacturing jobs in the United States, and much more. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. We appreciate your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini-course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- SimpliSafe: Learn more at simplisafe.com/jordan

- Blindsgalore: Visit blindsgalore.com today and let them know we sent you

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- NetSuite: Defer payment for six months at netsuite.com/jordan

- Something You Should Know: Listen here or wherever you find fine podcasts!

Miss the show we did with Vince Beiser — author of The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization? Make sure to check out episode 97: Vince Beiser | Why Sand Is More Important Than You Think It Is!

Thanks, Chris Miller!

If you enjoyed this session with Chris Miller, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Chris Miller at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

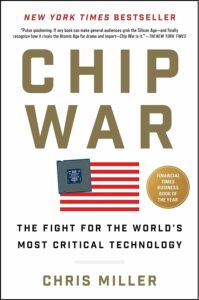

- Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology by Chris Miller | Amazon

- Chris Miller | Website

- Chris Miller | Twitter

- Chris Miller | LinkedIn

- What Is a Semiconductor and How Is It Used? | Investopedia

- The History of Semiconductors | Electronic Competence

- The Global Might of the Tiny Chip | The New York Times

- Chip War — Battle for the Globe’s Computing Power | Financial Times

- The US-China Chip War Is Reshaping Tech Supply Chains | Financial Times

919: Chris Miller | Chip War: The Battle for Semiconductor Supremacy

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:03] Chris Miller: If you asked, when will China catch up to the level of chip in my iPhone today? I'd say just a couple of years. But in a couple years, Apple's going to be producing chips that are substantially better than that, and so, the gap is going to remain. When will China catch up to that? Maybe in a decade, maybe never.

[00:00:24] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people and turn their wisdom into practical advice that you can use to impact your own life and those around you. Our mission is to help you become a better informed, more critical thinker through long-form conversations with a variety of amazing folks, from spies to CEOs, athletes to authors, thinkers to performers, even the occasional gold smuggler, economic hitman, drug trafficker, investigative journalist, or tech luminary. And if you're new to the show or you want to tell your friends about the show, and I always appreciate it when you do that, I suggest our episode starter packs.

[00:00:57] Well, first of all, it's a great place to begin, hence the name, but there are collections of our favorite episodes on persuasion, negotiation, psychology, geopolitics, disinformation, cyber warfare, crime cults, and more that'll help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/ start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started.

[00:01:16] Today, semiconductors are the atomic weapons of the modern era. It's really hard to overstate how important these things are. There's a dozen or more in every smartphone. Apple, whose phone you might have in your hand right now, they don't make any of them.

[00:01:29] I think that's starting to change, but they don't make their own semiconductors. Most things you buy that have these things and rely on them. They don't make them. They're all made in pretty much one place, which is Taiwan, which is kind of amazing. I mean, yes, there are exceptions to this, but it's like huge amount of market share over there. We'll explore just how much.

[00:01:46] In the beginning, this was, of course, all about guided munitions, smart bombs, military innovations, often drive civilian innovation. And we're going to go through that process here on this episode. It's quite fascinating. Today, we'll explore why chips are as important as other resources like oil and gas.

[00:02:01] Yes, they are that foundational, and why making them and manufacturing them and distributing them is So, difficult, requiring nation state programs to accomplish, similar to a space program, a vaccine program. It might even be more complex than a vaccine or a mission to the moon. It's really super impressive how these things are made and what they can do.

[00:02:20] It's really super impressive, the scale of these things. We'll also, deal into the fascinating history of semiconductors. I know that sounds kind of boring. But the Russians, the Soviets were stealing them. China's obsessed with creating their own. And we're going to talk about why China can't currently compete with the US or even Taiwan when it comes to manufacturing these things.

[00:02:38] And finally, we'll discuss the US CHIPS Act and what might happen if China decides to take military action against Taiwan, and what semiconductors, the role semiconductors might play in such a conflict. Enjoy this inside look at these tiny machines that guide our modern lives.

[00:02:53] Now here we go with Chris Miller.

[00:02:59] I have to say, man, I was surprised that there are semiconductors that are smaller in scale than a virus. Because after COVID, now we all know how big a virus is because everybody was doing a meme about how the masks don't work and the viruses are small. So, to have a semiconductor be that small is really, impressive is kind of a crappy, understated word for that. We're manufacturing electronic devices that are running the whole world and they're that small, it's mind blowing.

[00:03:29] Chris Miller: That's what makes computing so powerful today, that inside of your smartphone there are 15 billion virus-sized devices called a transistor that make all of the ones and zeros that all computer requires.

[00:03:39] Jordan Harbinger: I remember reading in the book that something like more semiconductors or more transistors were manufactured last year than the quantity of all other goods produced by every industry in history or something like that. Give me the correct version of this because that was also mind blowing. It's hard to imagine.

[00:03:56] Chris Miller: Yeah, that's right. We produced more transistors than the combined quantity of all the goods in all of human history just last year. We produced them by the quintillions, 10 to the 18th.

[00:04:06] Jordan Harbinger: And for people going, “That's impossible. there's not that many chips.” These are not the actual chip that you see, right? In that chip, there's how many transistors are in there?

[00:04:15] Chris Miller: Yes, if you take your smartphone, for example, it'll have 10, maybe 20 billion transistors inside of just the main chip on your smartphone.

[00:04:21] Jordan Harbinger: And transistors, when I was a kid, I used to rip apart radios, and you'd see the transistor, and it was like this black plastic, semi, kind of a, I don't know, cylinder that was cut in half and had three leads coming out of it. Is that just one transistor in there or are there multiple in there, too, and that's just what we just called that a transistor.

[00:04:39] Chris Miller: I think you're referring to just one transistor and basically all progress in computing has been shrinking them smaller and smaller and smaller every single year.

[00:04:46] Jordan Harbinger: So, that black plastic doodad that I ripped out of a radio in 1987, which is probably designed somewhere in the ‘70s or early ‘80s, that thing is now so small that you can fit billions of them into my smartphone on various chips.

[00:05:00] Chris Miller: That's right. And the billionth of a meter is how they're measured today.

[00:05:02] Jordan Harbinger: Right. So, you see like the three nanometers and like, that's the stretch. It's just absolutely incredible. I know people are like, “Get over it. It's just a chip.” But I think marveling at that is worth doing because it really shows you how advanced technology has become, and of course that's why these things are so damn important to running the entire world. Tell us about Moore's Law, why things have actually shrunk to this degree.

[00:05:24] Chris Miller: So, if you go back to the first chips that were available in the 1960s, they had just a handful of transistors on them, because transistors were large, they were large enough to see. And so, Moore's Law has been the process of shrinking the size of transistors down so you can cram more of them onto each chip. And it turns out that we've been able to produce roughly twice as many transistors on chips every single year or two over the past half century, which is why we get from four transistors in the first chip that was available to 15 billion transistors in the chip on your iPhone.

[00:05:55] Jordan Harbinger: But that law doesn't extend forever, right? People always go, “Wow. Well, Moore's law is slowing down. So, something, something the United States is going to decline.” I don't know. Whatever their argument is.

[00:06:04] Chris Miller: Yeah, it's not really a law, actually. It's a prediction that Gordon Moore made in 1965 and it's been proven true since then, but it's not guaranteed to continue. And at some point, it will fail because we're going to hit physical limits to how small you can actually shrink an individual transistor. But for now, at least for the next decade, we've got a clear line of sight to shrinking them down even further.

[00:06:23] Jordan Harbinger: Chips are largely the bottleneck in production of just about everything modern from what I understand, right? So, is this why we couldn't get cars during the pandemic? Because there's so many chips in cars, and there were none to be had?

[00:06:34] Chris Miller: Yeah, that's right. The typical new car has a thousand chips inside, some pretty simple like the ones that make your window move up and down when you press the button. Others super complex, like if you have a Tesla, the automated driving systems are run by an ultra-complex processor chip. And during the pandemic, there were huge shortages, and so car companies often couldn't finish their cars. They were missing just one of the thousand chips inside of them.

[00:06:56] Jordan Harbinger: The supply chain of this is bananas. And it also, sort of shows, since it's so fragile, how fragile our economies really are. Because I've heard the expression data is the new oil.

[00:07:05] But I think you say in the book, the pumps and pipes are all powered by semiconductors. Can you describe for us the stats and the stakes about just how reliant the world is on semiconductors? Because it's, yeah, you can't get cars, that's pretty bad. But if you can't get phones, and you can't build computers, and you can't get cars, and you, I don't know, can't run the internet, there's not a whole lot left, man, for the modern man, is there?

[00:07:29] Chris Miller: Yeah. I mean, today, pretty much anything with an on-off switch has at least one, and often dozens or hundreds of chips inside. So, it's your refrigerator, it's your dishwasher, it's your coffee maker. Almost anything that has electricity going through it has a bunch of chips inside. And so, that makes the entire economy reliant on chips, and most of these chips are produced by just a small number of companies.

[00:07:52] Jordan Harbinger: Okay. So, can't an earthquake or I don't know, to be dramatic about it, a missile strike could not throw chip manufacturing into pure chaos and send prices through the roof? Because we had the pandemic, but for what I understand from that is, that was more a failure of prediction, “Oh, we're not going to have that much demand. Let's scale down production voluntarily.”

[00:08:12] “Oh, wait, look, the demand is way up. Turns out we were wrong. Let's scale things back up,” and it just took time. That probably takes less time than if a cruise missile slams into your primary manufacturing facility and you have to repair the whole thing, right?

[00:08:22] Chris Miller: That's right. And we've made the decision to put most of the world's key chip industries in seismically active zones like Silicon Valley or Japan, or Taiwan.

[00:08:31] Jordan Harbinger: Great.

[00:08:33] Chris Miller: So, there's plenty of scope for just one accident to cause huge disruptions.

[00:08:37] Jordan Harbinger: The transistor that came out of my radio, that was even then pretty small because I've taken apart old TVs. I'm not sure how big of a nerd you are. I'm getting, I'm going to go out there and guess. Since you wrote a book on semiconductors that you're, you're going to be able to follow my nerdiness on this.

[00:08:51] I used to take apart old televisions and, well, I almost killed my friend because it had vacuum tubes in it that hold electricity for, you know, like three years after they're charged or something, and he got shocked and flew across my garage. But vacuum tubes, those were the original transistors, right? Those are the sort of the original electronic on-off switch as we would know it today.

[00:09:12] Chris Miller: Yeah, that's right. So, if you go back to a computer from like the 1940s when computers are the size of rooms, they wouldn't have any transistors. They just had vacuum tubes, sort of like light bulbs, you turn on and off. And they had two problems. One was that they were really hard to miniaturize. You couldn't make them that small. But the second problem was that because they were like light bulbs, they emitted light, it would attract moths. And so, there's a constant problem of debugging, which at the time at literally extracting moths from your back of your vacuum tubes, they would malfunction.

[00:09:42] Jordan Harbinger: So, debugging was literally scraping burned insects off the outside of these tubes?

[00:09:47] Chris Miller: That's absolutely right, yeah.

[00:09:48] Jordan Harbinger: Huh! Copying semiconductors and reverse engineering them, why is it so hard to do? We've heard a lot of bluster from China, right? And they're like, “Look at what we made our domestic semiconductor.”

[00:10:00] And then it's like a white labeled Intel chip. Someone gets ahold of one and I don't know what they do. They go in there. They go in the firmware on the chip. And it's like, this is literally just Intel. It's an Intel chip that they like scratched off the outside and printed a Chinese brand. And it redid some code so when it boots, it doesn't say Intel on the screen.

[00:10:18] Why is it so, hard to do this? You can steal them, you can buy them, but you have no idea how it's made. It's like buying a cake and then trying to figure out how it's baked. Why can't people just look at the thing and make machinery that creates this?

[00:10:31] Chris Miller: Yeah. Well, if you think of a cake, there's, you know, a dozen ingredients in a typical cake recipe, but there's a thousand ingredients in a typical chip recipe, including some really complex chemicals, some really sophisticated design methodologies.

[00:10:46] It's one of the hardest things we put together as humans. And so, just like you can't look at a cake and extract the recipe, well, it's orders of magnitude more difficult to try to extract the recipe as to how to make it chip. That's one reason. The second reason is that in the time it takes to copy, your competitor has already raced ahead due to Moore's Law because companies are issuing new chips every year or two that are twice as good as the prior version.

[00:11:09] So, even if you do a successfully copy, you're guaranteeing that you're far behind the cutting edge.

[00:11:14] Jordan Harbinger: Basically, you could try to do this, but you're going to be — you're going to end up being three or four or more revisions behind. And I guess that's not the end of the world if you're a developing country and you just have no chips.

[00:11:24] But I guess even then, if you're a developing country, it's still going to be way cheaper to purchase these from countries that can make them versus trying to get — because the talent level and the machinery and everything required for this, it seems like it's kind of like the space program.

[00:11:39] You can't just throw money at the problem. You need money, talent, infrastructure. And even then, it's you're going to the moon, and sometimes literally, in the case of the space program.

[00:11:49] Chris Miller: You know, I think it's far harder than the space program, because to get to the moon, you need to get to the moon once or twice or three times. But for chips, you need to make virus-sized transistors by the billions for every single chip you produce. There's a mass production aspect to it that's much harder than space.

[00:12:04] Jordan Harbinger: You know, that makes sense. I didn't think about that, because you can't just make a slightly bigger chip that does the same thing. It would have to be like this massive, I mean, to fit 20 billion transistors on something, it could be the size of my entire lot that my house is on, if you don't know how to miniaturize it, which makes it useless for the purpose that it is going to be used for. Like if it's a mobile phone, it doesn't fit anywhere in your garage, you have an issue.

[00:12:26] Chris Miller: Right.

[00:12:27] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Okay. So, what is it with China sort of larping that they have their own chips that it turned out to be stolen? Or I should just say white labeled Intel chips. Why bother?

[00:12:37] Chris Miller: In China, there is tons of government money available for anyone who says, “We're going to catch up to the cutting edge.”

[00:12:44] And so, there are lots of companies in China that have schemes to make it look like they're catching up to the cutting edge because they can attract a lot of funding in response. There are different ways you can do this. You can build factories and say, “My factory is at the cutting edge. You can develop a chip. And my chip's at the cutting edge.”

[00:12:59] And if you succeed in convincing the Chinese government that you've got something special, they'll give you huge sums of money, hundreds of millions, billions of dollars. And so, people have built scams around milking the Chinese government of subsidy money that's intended to build a chip industry.

[00:13:12] Jordan Harbinger: I see. So, you don't think it's just soft power like, “Look, we built our own chip.” You think it's more like they're literally just scamming the government and saying, “Look, we built our own chip. Give us money.” And then that guy just vanishes into —

[00:13:25] Chris Miller: Yep.

[00:13:26] Jordan Harbinger: Western Europe or something. Interesting. I've heard of scams happening in China with those subsidies, maybe it just seems a little bit too brazen to try and scam your own government out of hundreds of millions or billions of dollars when your own government, especially it's an authoritarian government that might not just be like,” Oh, well, that guy really pulled the wool over our eyes.” I mean, I wouldn't screw over Vladimir Putin. It seems like a bad idea. People have tried recently.

[00:13:49] Chris Miller: Yeah. It's a risky strategy, but it's a profitable strategy, too. And so, there's a bunch of great examples of just blatant frauds that have been successful in getting government funds over multiple years to build advanced semiconductors or to say they're building advanced semiconductors.

[00:14:03] Jordan Harbinger: All right. Taiwan, they became interested in the semiconductor business. Why? It seems very random to have this little island that is essentially and for many years was almost like kind of a backwater retreat location for the, was it Kuomintang Party, Chiang Kai-shek during the revolution in China.

[00:14:22] And then suddenly, I don't know, we wake up, I wake up out of not paying attention to this kind of thing for decades, and all of our semiconductors are made in Taiwan. It seems very random to me. I mean, I read the book, so I understand kind of the process, but what happened there?

[00:14:37] Chris Miller: Two things happened. First, the Taiwanese government correctly realized that semiconductors and electronics in general could provide a ton of jobs for Taiwan. So, Taiwan was an agricultural society that lots of farmers were moving to cities looking for a job.

[00:14:51] And so, they said, building electronics factories and chip factories is a way to employ lots of people. That was that was the right path. But the second thing that they did is that they hired an individual named Morris Chang who founded the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company in 1987 with a brand-new business model.

[00:15:08] He said, “We're not going to design chips like most companies did. We're only going to manufacture them.” As a result, grew to be the biggest chip maker in the world. And so, they put all this money behind Morris Chang. He built what today is the world's most important chip maker.

[00:15:21] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like you would be better off designing your chips and making them, but that turned out to be kind of a bad idea to do. Well, I shouldn't say a bad idea. It was a better idea to not design your own chips, but why?

[00:15:32] Chris Miller: The intuition is sort of like Gutenberg and books. Gutenberg didn't write any books. He only printed them. And as a result, he was able to get really good at printing books. Morris Chang wanted to do the same thing with chips.

[00:15:43] He said, “I'm not going to do any design. I’ll leave that to the design experts. I'm going to get really, really good at manufacturing chips. And then I can provide manufacturing services for lots of different customers and scale up,” build this huge scale because he produces chips for Apple, for NVIDIA, for lots of different companies.

[00:15:59] Jordan Harbinger: I suppose also, if you're manufacturing chips and you design them, you're going to make competition where there wasn't any, right? So, if you're designing chips and Apple buys them, other people aren't either going to not be allowed to buy from you or are going to be like, “I'm not going to give you my design when you're also doing designs for Apple because you're just going to steal my design and give it to my competitor.”

[00:16:20] But if you're just making chips and you have no input on what the end result really is other than having manufactured it instead of designed it, everybody's giving you the top end, most advanced stuff at all times and pushing your manufacturing chops forward because they want more and more transistors at a smaller and smaller scale.

[00:16:38] Chris Miller: That's right. If you think of yourself and Apple shoes, they've got this ultra secretive, complex technology that they have to trust their manufacturers with. And so, they're only going to trust a company that they think is a neutral player. And that's what TSMC has been.

[00:16:52] Jordan Harbinger: Do you think it was a conscious decision on the part of Morris Chang and the government of Taiwan to be indispensable?

[00:16:58] And not just for jobs sake, of course, in Taiwan, but also, to say, I mean, now they call it the silicon shield, right, like, “The United States has to defend us because we make all the chips for the whole world.” Was that a conscious decision or was it, did they just sort of wake up one day and be like, “Dang, we are really the linchpin of the economy. That's good for us. Let’s keep it rolling.”

[00:17:18] Chris Miller: No, I think even they are surprised at how successful they've been. But it was definitely conscious to inject themselves to the center of the chip supply chain and make all Silicon Valley companies dependent on their manufacturing. That was deliberate. It was a strategy they developed decades ago that's just bearing fruit today.

[00:17:34] Jordan Harbinger: Okay. I wondered about that because it just seems like either, man, are they playing 4D chess or this was a really big lucky break that they then capitalized on appropriately.

[00:17:44] Chris Miller: 4D chess probably isn't, but they were looking very far ahead. They saw the way the industry was changing, and they wanted to put themselves right at the center of it.

[00:17:52] And, you know, Taiwan's in some ways seems like a really obscure place to have all this advanced chip manufacturing. But in other ways, there are such deep personal connections between Silicon Valley and Taiwan. So, if you talk to Taiwanese chipmakers, you never know, are they in Taiwan or are they in California?

[00:18:07] They're back and forth all the time. It’s these personal networks as well that really linked up Taiwan and Silicon Valley.

[00:18:11] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I mean, my wife, she's American, but she's Taiwanese. Her family's Taiwanese. They came here in part because of other people in tech and that whole thing. I mean, they came right sort of early in the Taiwanese community here is very much ingrained in the tech sphere, right?

[00:18:28] It's just a massive amount of Taiwanese people that have been here since I guess the ‘80s and ‘90s at least. In the early days, it sounds like Japan was poised to take this over. And I vaguely remember as a kid, all the high-tech electronics were always out of Japan, right? And I'm thinking of Sony Walkman specifically because that kind of defined my generation in many ways.

[00:18:46] But it seemed like anything high tech was Japan. Did that shift or was that just a weird perception that I have from my youth?

[00:18:53] Chris Miller: That's right. Japan really fell behind the curve in the 1990s and 2000s. They were high tech in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but then they missed the PC, they missed the smartphone. And so, today Japan plays a really important role in producing a lot of the subsystems, for example, in smartphones, but there's not a single smartphone brand in Japan.

[00:19:15] That was a huge error on their part because they had a really enviable position and they lost it almost all of it because they couldn't keep up.

[00:19:21] Jordan Harbinger: They tried to leverage their industry a little bit and again I'm going off like really sort of vague memories from back in the day but I kind of — correct me if I'm wrong, did they not sort of try to get leverage in the electronics industry, and then indicate that they had us by the short and curlies and that they were going to potentially use that leverage against us?

[00:19:41] It probably didn't make us not want to do business with them, but certainly we were open to doing business elsewhere if we were doing business with them. It's like what China's doing now. “We're not going to supply you with rare earth metals.” “Okay, thanks for the warning. We're going to literally find anywhere else to go get those things now that we know you're going to not deal in good faith.”

[00:19:57] Chris Miller: Yeah. And if you look at Korea or Taiwan, their rise in tact and electronics really began in the 1980s, which is when Japan was number one. And so, the U S firms would go to Korea, go to Taiwan, and say, “Hey, we're looking for alternative sources of supply,” and help build up companies in other countries in response.

[00:20:16] Jordan Harbinger: Why didn't the Russians end up doing this or the Soviets, I should say, back in the day, because this is sort of peak Cold War, right? They're developing these things. They for sure had hundreds or thousands of agents just trying to steal this kind of stuff because computers were, it was no secret that these things were going to take over the world in the ‘80s and ‘90s, especially. They must have tried to go for this.

[00:20:36] Chris Miller: Well, they had agents all over the world, in Silicon Valley, across the US, across Europe and Japan, and they succeeded in doing a lot of smuggling. It was actually so advanced that in the Soviet Union, the entire country was on the metric system, but the chip industry was largely measured in inches because they smuggled in so much equipment from abroad.

[00:20:55] All the smuggling didn't really work because of the same copying problem we mentioned earlier. They copied, but at a long lag. And in doing so, they failed to actually innovate on their own. On the one hand, you could find a lot of Soviet military equipment that actually had American chips inside of it.

[00:21:11] But it was always older generation chips that were never cutting edge, and they couldn't find the most effective way to use them. And so, the Soviet military simply had no access to cutting edge chips.

[00:21:21] Jordan Harbinger: I mean, it's sort of ironic how that's playing out now. Aren't they finding drones that are blown up over at Ukraine, and they're loaded with Korean chips and Taiwanese chips and American chips?

[00:21:30] I mean, I don't know if this is an exaggeration, but you hear like, “Oh, they've ripped this out of a dishwasher and put it into this missile.” I don't know if that's really happening or if it's just an exaggeration, sort of a meme on Reddit, but it doesn't bode well for them manufacturing their own stuff.

[00:21:44] Chris Miller: Yeah. I mean, it's certainly true that they're packed with Western microelectronics with American, Japanese, Korean. And the fact that they've bet their military equipment, the most sensitive equipment on our chips shows just how far behind they are.

[00:21:56] Jordan Harbinger: I can also, not imagine that if you're smuggling equipment in from abroad back in the ‘80s or the ‘90s, how do you make spare parts for that equipment, right?

[00:22:05] Because that's also, manufactured in the United States or Korea or wherever. And you've got all your troubleshooting stuff, all your tools, everything is all in either inches or just not made in your country. And I know United States, one of the things that people gripe about when you see arms deals with like Saudi Arabia is people say like, “Oh, what if they run loose with this?”

[00:22:26] And it's like, they can't. they need all these tools, all these software updates, all these training technicians and parts. I mean, we basically make any company that buys anything high tech from us totally reliant on our supply chain and maintenance. And you would just end up doing that to yourself as a country if you try to copy our tech. So, it seems like it made the Soviets reliant on Western technology that they couldn't really get.

[00:22:47] Chris Miller: Yeah. No, it's a bad strategy. It binds you into having to keep smuggling in our tech to keep updating your systems. But, you know, the other problem that they had is they never knew what type of chips they were smuggling in were real and which ones were counterfeit.

[00:23:02] And they were convinced, and we don't really know, they were convinced that the CIA was giving them counterfeit or chips that were manipulated by the CIA to function in different ways. There's actually today in the Russian security services, the FSB, a division whose job it is to look at equipment they're smuggling in and try to ascertain whether it's been compromised in some fashion.

[00:23:21] Jordan Harbinger: Really? I guess that makes perfect sense, right? Because if we know you're smuggling this in and that it's probably going to go into a MiG or a piece of artillery, wouldn't it be great if it could be shut down remotely, or at a very inopportune time? And so, someone’s job is to make sure that that chip doesn't have whatever firmware on it that we might have put in there, like a backdoor or something along those lines.

[00:23:42] Chris Miller: Yeah. And of course, the Chinese are doing this to us right now.

[00:23:45] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:23:46] Chris Miller: We've only got a vague understanding of who's meddling with the components in our systems.

[00:23:49] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I was going to ask about that because you hear about Huawei and 5G, and the phones being banned. At first, I was like, okay, is this to keep them from competing with our phone companies?

[00:23:59] Or are they actually really worried about software back doors? And it seems like you really could be, especially at the infrastructure level. Like maybe they don't put it in your frigging phone, who cares? But what if they put it in the 5G cell tower technology that they're selling to Africa, and that just funnels data back to China? That's industrial scale espionage, I guess, for lack of a better word.

[00:24:21] Chris Miller: Yeah, and I think if you look at the history of telecoms companies in any country in the world, there's not a single one of them that has not been used as a tool of espionage by the government that they're located in. Certainly, the US has a long track record of doing exactly that.

[00:24:34] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, wow. So, you think it's quite credible that Huawei or some other Chinese companies were doing this?

[00:24:40] Chris Miller: I would be shocked if the Chinese government weren't trying very hard to use every mechanism they’ve got.

[00:24:44] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I suppose you're right. I wonder, is there like, evidence of this that is public or is it just like, they're probably doing this?

[00:24:52] Chris Miller: There's certainly evidence that US servers have been discovered with additional components on them that weren't supposed to be there. What they were used for, hard to say. But in a circuit board in a server, there's hundreds of components, even more, and so, you often don't know which components used for which part.

[00:25:09] So, it's a little bit circumstantial evidence, but I think coupled with the obvious rationale, China wants the data, China wants the intel, I think would be naive to think it wasn't happening.

[00:25:23] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Chris Miller. We'll be right back.

[00:25:27] This episode is sponsored in part by SimpliSafe. As the holiday season rolls around and we are pulled into a whirlwind of festivities, SimpliSafe becomes the unsung hero in our household. What gives us peace of mind is knowing that SimpliSafe offers comprehensive protection. We're talking advanced sensors that have your back against break ins, floods, fires, and more. Those sneaky porch pirates that can't escape the vigilant eyes of SimpliSafe's HD cameras both indoors and out. I definitely remember many times when I lived in Michigan, things would freeze and flood, and that cost way more than a security system, let me put it that way. What's even more incredible, top tier security won't break your bank. You get 24/7 professional monitoring for less than a dollar a day, and the showstopper is 24/7 live guard protection, paired with a smart alarm wireless indoor camera. That means monitoring agents can directly confront intruders, stopping crimes, or just harassing criminals as it happens. It's an innovation exclusive to SimpliSafe. If you're still on the fence, take it for a spin with a 60-day risk free trial and a full refund policy. You got nothing to lose. I haven't seen it lower than this deal. So, for a limited time, save up to 50 percent on any new system with a fast to protect plan. Visit simplisafe.com/jordan. There's no safe like SimpliSafe.

[00:26:34] This episode is also, sponsored by Blindsgalore. For at least two years, our windows went fashionably naked. Well, that wasn't the only thing that was naked, unfortunately, for the neighbors. We kept procrastinating the whole blinds buying ordeal, but that's where Blindsgalore swooped in, cape fluttering. This isn't just about dodging that morning sun sniper shot, though their solar powered roller shades are stellar for that. What got us hooked was how Blindsgalore turned what I expected to be a home improvement saga that was kind of just horrible all the way through into a breezy afternoon task. Their online ordering was really smooth, their customer service is really good, it was really fast to connect with a human on the phone who explained every little detail and question that we had. So, after dilly dallying for years, with Blindsgalore, we finally have our windows looking sharp. We've got a smart hub so, our roller shades automatically roll up and down at a certain time. I kind of feel like Iron Man, like they just open in the morning. They also, have shutters and custom drapery. Free shipping and order 15 samples for free to get started. Blindsgalore guarantees a look you'll love, and they've been doing it for 25 years. Check them out during their big birthday sale and let them know The Jordan Harbinger Show sent you. That party is going on right now, don't miss it. Get over to blindsgalore.com today.

[00:27:40] If you're wondering how I managed to book all these folks, I mean, you probably don't care, you don't have a podcast, but you realize that building relationships and having a circle of people around you is important. I hope you realize that. It doesn't matter what industry you're in.

[00:27:50] There's really no industry I can think of that is exempt from this. If you think you're exempt from this, send me an email. Even retired people are like, “It's so important for sanity.” So, I know that's everyone's favorite excuse, “I'm retired,” or “I don't need it”. You need it and it's good for you. We've seen on this show how it helps you live longer, and relationships and happiness are immediately correlated and causal. So, anyway, this course that I'm giving away for free over at jordanharbinger.com/course doesn't have any upsells. I don't need your credit card number. It's not cringy. It's not awkward. It takes a few minutes a day. It's not a big-time commitment. And many of the guests on the show subscribe and contribute to the course. So, come join us. You'll be in smart company where you belong. I'm done selling it to you. It's free anyway, over at Jordan harbinger.com/course.

[00:28:32] Now back to Chris Miller.

[00:28:36] I'm never going to be skeptical. If you tell me China or another country, including the United States is spying on somebody else.

[00:28:41] It's one of those things where you hear about it so much, but it's like, is there just evidence or is there actually just only speculation? It's hard to tell now because people don't really care. They'll write an article about something like it's complete fact, when it's just speculation from the opinion section, white labeled into something else. China imported more semiconductors than it did oil last year. Is that accurate?

[00:29:04] Chris Miller: That's right. And for the last decade, China has spent as much money each year importing chips as oil.

[00:29:08] Jordan Harbinger: Can you scale this for us? Because I mean, I know countries need a lot of oil to keep their economy running, but it's hard to wrap your mind around just how much that is.

[00:29:16] Chris Miller: It's tens and tens of billions of dollars a year of chips. And the reason China imports so much is first because it doesn't produce any cutting-edge chips at home. But second, because most of our phones, our computers, consumer electronics, they're all assembled in China. So, China's got to buy all the chips needed for all these devices.

[00:29:35] They're assembled in China and sent all around the world. So, the largest share of the world's chips that are produced end up transiting through China at some point.

[00:29:43] Jordan Harbinger: 260 billion was the figure that I saw, which is actually more than all of the oil exports of Saudi Arabia. That's how many chips China is buying.

[00:29:52] Chris Miller: That's right. But it makes sense when you think that, you know, Saudi Arabia, we associate Saudi with oil. But Saudi produces 10 to 15 percent of the world's oil. TSMC produces 90 percent of the world's most advanced processors. So, China's just got to spend huge sums of money buying chips largely from Taiwan.

[00:30:08] Jordan Harbinger: Gosh, TSMC, for those in case you forgot, that's the Taiwan manufacturer of, well, 90 percent of the chips that we use. When you say high end, what are we talking about? Where's the dividing line between a chip that goes into a smartphone, which I assume is what you mean by high end or into a computer. What's a low-end chip, like one that turns on a flashlight with a button?

[00:30:27] Chris Miller: Yes. So, even within your smartphone, there's dozens of semiconductors. The application processor or the one that's running iOS, if you've got an iPhone, that's a very advanced chip, 7 nanometer, 5 nanometer, depending on how new your phone is. But then there's also lots of simpler chips. The power supply is managed by a simple chip, the Bluetooth, the Wi-Fi, the camera. Basically, the more powerful the processing, the smaller the transistors, the more advanced the chip.

[00:30:53] Jordan Harbinger: The reason this is kind of important for me is because I don't really know if people understand that a “high-end chip” still does relatively simple things in our mind because we're so used to seeing what those are.

[00:31:05] I have a timer here. It's a little black and white digital. This is probably a low-end chip, would you say?

[00:31:11] Chris Miller: That's right.

[00:31:12] Jordan Harbinger: This is essentially a clock with a button on it. I mean, there's not a whole lot else going on. But I've got something else here that's like an application launcher. It's called a Stream Deck.

[00:31:19] That thing, I'm guessing, has dozens or hundreds of not low-end chips inside it because it's got a colored screen, and the buttons do things on my computer. So, I guess what I'm trying to say is the bar for what a high-end chip is actually relatively low.

[00:31:34] Chris Miller: That's right. And every smartphone has multiple high-end chips in it.

[00:31:37] Jordan Harbinger: So, why is it that China can't just build fabrication plants, right? You mentioned there's inner jostling to try and look like you're doing something. I assume that plays a role because if you're busy trying to fake it, then you're not necessarily busy trying to do the real deal. But what else? Because China is a world power, they have nukes, they have an aircraft carrier, debatable about whether it works, right? They got submarines and stuff like that, satellites. They've gone to space. Why the hell can't they build a smartphone?

[00:32:06] It seems very difficult to wrap my mind around why they can't do something that seems simple enough for other developed nations to do, but apparently is incredibly, incredibly complicated.

[00:32:18] Chris Miller: Two reasons. First is that the know-how involved in cutting edge chipmaking is just so specialized and so unique. You can only learn it while working at another chip company.

[00:32:29] There's just a small number of people in the world that have any idea how to do this. And most of them are employed by competitors that don't want to let their employees go work for Chinese firms. Second, if you want to make a cutting-edge chip factory, you need to acquire tools from just a tiny number of companies in the US, Japan, and Netherlands, and those companies are not allowed to sell their tools to China. So, you can't get the manufacturing equipment you need in China.

[00:32:54] Jordan Harbinger: Okay, not being allowed to sell your equipment to China, fine, but can't they sell it to Vietnam and somebody in Vietnam smuggles it in? I mean, come on, it's the world power. They can get a machine, right?

[00:33:05] Chris Miller: The machinery in question is the most complex machinery humans have ever made. So, I'll give you one example, called a EUV photolithography machine.

[00:33:13] This is just one of the types of tools needed to make a chip. It's produced by one company in the world, in the Netherlands. It's so big it requires three airplanes to move. It costs $150 million apiece, and some of the components inside of this machine include the flattest mirrors humans have ever made. One of the most powerful lasers ever deployed in a commercial device and an explosion happening constantly inside the machine at a temperature of 40 times the surface of the sun.

[00:33:39] Jordan Harbinger: Okay. Wow, that's eye wateringly complex. And it seems like not only is it complex, it sounds fragile, because if you need the world's flattest mirror, you can't even have people in there walking around because it'll vibrate or something in a weird way, right?

[00:33:53] It's just, you can't just throw that thing on the floor of a factory with other machinery that's vibrating. It's got to be perfectly still, and it's got to be perfectly stable, and it's got to have the right environment around it. I mean, you think those clean rooms where you can't have dust in there, I mean, that's the easy part.

[00:34:08] Chris Miller: Yeah, that's right.

[00:34:09] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:34:10] Chris Miller: And so, these tools, just to make them operate, you have to have personnel from the company that makes them on site for the lifetime of the tool. So, you can't just sell it to Vietnam and then smuggle it across the border in a couple of trucks. This is a operation just to move it and install it. You need the approval and the personnel from ASML, which makes the machine.

[00:34:30] Jordan Harbinger: And they know where their bread is buttered and they're not going to send a technician to another country because if they get blacklisted, somehow, it's over? Or if they get sanctioned, I guess? I mean, what would happen, right? They would get sanctioned or fined?

[00:34:42] Chris Miller: Fined and sanctioned, that's right. And ASML, it's a Dutch company, but because their machines are so complex, they've got to source components from all around the world. They've got, the mirror is actually from Germany. The laser is from a different German company. But some of the key components in these machines are actually made in the US, in California and in Connecticut.

[00:35:00] And so, they're just as reliant on the US as they are in Netherlands for the construction of these machines.

[00:35:07] Jordan Harbinger: I think you'd mention in the book, there's one of these, was this the etching laser? Is that the machine you just described? It's got 450,000 different parts just in the laser itself.

[00:35:17] And of course the defect in any one of those parts is going to make it not work or cause delays. So, even if you steal the entire design process, you probably don't even know what you're looking at, at that point, right?

[00:35:28] Chris Miller: That's right. And there's, you know, this company has thousands of employees, but no one outside of this company has any idea how to make one of these tools.

[00:35:35] And even if you copied and pasted the blueprints and downloaded them to your computer, you can't just go to the company that makes the mirrors and order an extra mirror. You know, the supply chain is intimately bound up with this one company. So, where would you even start if you're trying to replicate the machine? It's basically a hopeless task.

[00:35:50] Jordan Harbinger: Gosh. You'd need your own domestic industry for each of these parts, and we don't even see that in the US or the Netherlands. And then whatever, your whole team needs a PhD, and laser optic semiconductor design or whatever field this is to even look at the thing you stole from the company that you stole it from.

[00:36:07] Chris Miller: That's right. And by the time you've made any progress, they're going to have delivered their next generation system, which is substantially more effective.

[00:36:15] Jordan Harbinger: I know China metals a lot in their domestic industry. And yes, some of its subsidies, which I'm sure is great for business, but I think a lot of it, isn't it also, kind of like, “Well, this crony's got to get this. And so, we're going to put this factory over here,” even though it's not necessarily the best place for it. Is that hindering their ability to copy this or are they not even that far yet?

[00:36:34] Chris Miller: There's a ton of that dynamic. And if you look at the way China puts money into its chip industry, the dollar values are huge, tens of billions of dollars a year.

[00:36:41] But it's divided among each of the provinces and each of the cities that everyone wants a chip making facility in their district or their cities, and they can have a good photo op in front of it. And so, it's divided in super inefficient ways that as a result, they get much less bang for their buck in terms of investment than they could, if they were doing it smarter.

[00:37:00] Jordan Harbinger: I do want to talk about Chinese investment, but it's occurred to me that even if you somehow could copy this, you need — how old is that Dutch company? It's got to be several decades old now, the one that makes the laser and the other UV machine.

[00:37:12] Chris Miller: That's right.

[00:37:13] Jordan Harbinger: So, you can't copy that without that experience. You'd have to bring the talent over and the supply chain, which is, I assume, illegal in every sense.

[00:37:20] Chris Miller: Yes. It’s certainly illegal and, you know, good luck hiring them. How are you going to hire a thousand experts in this field? They're all currently employed at this one company. There's no other workforce you can draw from.

[00:37:31] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, you'd have to throw money at the problem, but if it's illegal, it's illegal. Those people might want to raise, but I don't know if they're going to give up their citizenship and their country to get it. That's a tall order. I know we've done something to stop China from buying chips overseas, buying equipment and things like that.

[00:37:47] Has that not spurred a bunch of investment? Are they trying to do this or like I said before, I know they're trying to fake it, but are they making headway and trying to do this? Because it's not like China to just say, “Well, we were never going to figure this out. Let's give up.”

[00:38:00] Chris Miller: Well, they've been trying for the last decade since 2014, tens of billions a year into the chip industry.

[00:38:06] They've made some progress in certain spheres to certain types of memory chips. For example, they've gotten pretty close to the cutting edge, but across the supply chain, across the industry, they're still far, far behind. The controls that the US put in place last year, banning the transfer of chip making tools and certain AI chips called GPUs to China. On the one hand, they provide a bit more incentive for China to try harder, but China’s already been trying really hard and spending lots of money doing so.

[00:38:34] So, I don't really think the new US controls are going to dramatically change things for China.

[00:38:38] Jordan Harbinger: Should we be concerned about China invading Taiwan from a semiconductor perspective?

[00:38:44] Chris Miller: I don't think China's going to invade Taiwan because of semiconductors, but I think if China does blockade or attack, one of the many bad consequences would be a catastrophic disruption to chip production.

[00:38:56] I think the Chinese know that if they were to blockade or attack, the chip industry in Taiwan would shut down immediately. It wouldn't have the power it needs. It wouldn't have the chemicals that are important. It wouldn't have any of the components that are required. So, it would just go dark.

[00:39:10] Jordan Harbinger: Ah, okay. So, you don't think there's a scenario in which they're like, “Look, we're taking over, keep the presses running. We still need these semiconductors,” because that's not going to work given the supply chain requires things from outside Taiwan and those things would be blockaded or cut off.

[00:39:22] Chris Miller: That's right. You need the components from outside of Taiwan and you need the engineers in Taiwan to stay at their jobs under an occupation regime. Good luck.

[00:39:30] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, good luck. I mean, I kind of figure I've got this, I won't say conspiracy theory because, you know, I'm anti conspiracy theory. But it's, I do have it in the back of my mind that that factory may or may not have explosives wired underneath it or at least be on a map for where the cruise missile goes in the event of taking over.

[00:39:48] But now the more you explain this, the more it seems like you really don't even need to level the factory if it gets taken over by China, because if the employees don't want to work there, or even if they are forced to work there, and the factory's operational, they're going to make a couple more runs of chips and they're going to go, “Hey, we need this, this, this, this, this, and this.” And it all comes from America and we're not getting any more of that ever.

[00:40:09] Chris Miller: That's absolutely right. And So, China would be foolish to think that it could actually take these facilities in an operational way. Maybe they're naive enough to think that, but it's just a hopeless goal.

[00:40:20] Jordan Harbinger: How do we ensure that countries like South Korea, then, don't help China manufacture their own chips? Are they also, disincentivized from doing that?

[00:40:28] Chris Miller: First is that the South Koreans are just as threatened by China as we are. They're looking at China, pouring all this money into the chip industry, and saying, “These are potential future competitors for us.” They've got no incentive to see them advance. Second, is that inside of every chip making facility in the world, including in South Korea, including in Taiwan, there's US tools, US software, US equipment. So, if anyone violates the rules, we can pull our equipment and their facilities just don't operate.

[00:40:54] Jordan Harbinger: How far away is China then from being able to build its own chips that fit into, I don't know, anti-ship missiles or AI weapons or building their own sort of GPUs? Are they able to build low grade versions, or can they not do this at all yet?

[00:41:10] Chris Miller: China builds a lot of low-end chips, mature technologies like you would find, for example, in a calculator or in your timer. But when it comes to anything high end, GPUs, smartphone chips, PC processors, these are things that China is years away from reaching the cutting edge at.

[00:41:26] Jordan Harbinger: When you say years, are you talking about like single digit years or are you talking about they need 20 years to be able to build a remote control for an Xbox?

[00:41:35] Chris Miller: If you asked, when will China catch up to the level of chip in my iPhone today? I'd say just a couple years. But in a couple years, Apple's going to be producing chips that are substantially better than that, and so, the gap is going to remain. When will China catch up to that? Maybe a decade, maybe never.

[00:41:51] Jordan Harbinger: Everybody needs the maximum cutting-edge chips in certain things. But if you can start to build, let's say you can build an iPhone 15, but you can only do it in 2026, okay. So, your phones and your consumer tech is a little bit behind, but a lot of your military guided missiles and things like that, I mean, that's fine.

[00:42:08] It's still just, it's good enough for that. It's just not good enough for you to have your AI beat our AI, or whatever it is at that point. But that's still quite worrisome, right? How does China get its military grade chips now? Does it literally buy them off the shelf?

[00:42:22] Chris Miller: It does. And so, military grade chips, there's, I think, two different categories to think about.

[00:42:25] One is the chips that are actually in the missile guiding it towards its target. And, you know, guidance is pretty easy right now. Your iPhone has great guidance. It can identify your location within a meter or two. Guidance used to be hard. Now, it's easy. The frontier is applying AI to military systems.

[00:42:42] So, looking at satellite data and identifying what's a tank and what's a truck, that's an AI problem that's already being addressed by militaries. Or if you're trying to communicate in a contested electromagnetic environment, your enemy is jamming the spectrum, you need to figure out how do you get communication to a different unit.

[00:42:59] Well, there's already AI systems that are trying to find where you can send your radio wave through. These are the actual frontiers, and this is where you do need cutting-edge chips because you're applying the most advanced AI systems to these problems.

[00:43:13] Jordan Harbinger: It sounds like basically what we're hoping is having high tech war will prevent low tech war because nothing is going to prevent lower tech war.

[00:43:20] We don't need chips or as many chips to do that, it still exists. So, you could still have like a pitched naval battle. The key is going to be your AI has already shut down their monitoring systems or something at that point, and they can't fight back because they don't have the chips to do it.

[00:43:33] Chris Miller: Yeah, that's right. You know, I think the way to think about this is, look, the Iranians have effective guided missiles. Iran has no tech sector, no chip industry, no nothing, but they can make guided missiles. Because guided missiles today are easy. It used to be hard. Now, they're easy. And so, if you want to be at the cutting edge, you better do something better than that.

[00:43:49] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like US dominance or Western dominance is dependent on high tech warfare because the size of forces is always going to be in China's favor, just like it was in the Soviet Union, right? They can get millions of soldiers to our several hundred thousand. So, we have to beat them on the technological frontier.

[00:44:06] We don't have a choice. We lose our advantage if we don't do that. If China is only a few years behind us, or maybe a decade or so behind us in making these high-tech chips, what are our options to slowing down their progress or stop halting their progress that doesn't involve us literally launching missiles at factories?

[00:44:24] Chris Miller: Well, I don't think we're going to halt their progress given all the money they've got and all the scientific expertise they got. But we're going to slow it down by doing two things. One is by stopping them from getting the tools, which we've been doing over the past couple years, saying “We've got equipment you need for chipmaking and we're not going to give it to you.”

[00:44:39] And two is by trying to drain their private sector of its expertise by discouraging people from working with the Chinese private sector, which ultimately is where much of the expertise comes from. Because the key with chips is that 99 percent of chips that are produced go to civilian applications and only 1 percent go to military applications.

[00:44:57] And so, if your country has a tiny private sector chip industry or a backwards private sector chip industry, you're going to have a backwards military chip industry, too, because they're so closely related.

[00:45:06] Jordan Harbinger: So, we have to essentially have better working conditions. Okay, check. Pay more. Well, debatable, but better quality of life.

[00:45:13] I know that a lot of folks are going back to China to work, at least Chinese people who come to the United States to study. Some of them have said they've done so under duress. Some of them said that they're getting paid more. But I think as my dad so eloquently puts it, “I don't see a whole lot of people swimming the other way.”

[00:45:29] I mean, he's not talking about China when he mentions that. He's usually talking about Cuba. But it does seem like this is a weird problem, right? Because we have to literally make the United States a better place to live, and so far it is because trying to help almost has to force people or bribe people to go and live there as opposed to just having a nice free environment where your kids can grow up and do whatever they want.

[00:45:50] You don't have to bribe your teacher, for example. So, that's good. We've got that going for us so far, which is nice. But what else can we do? Because authoritarian regimes, I mean, they can do a lot of sending people abroad and then forcing them to come home by threatening their family or whatever.

[00:46:05] Chris Miller: The other factor is that we're right now in the process of ripping apart the US and the Chinese tech ecosystem. For a long time, US firms thought it was in their interest and it was in their financial interest to help Chinese partners develop technologically. And that's why you've got so much US tech that's assembled, so much software that's written, so many business partnerships between US and Chinese firms.

[00:46:26] In the last five years, I've seen a lot of those partnerships being torn apart, partly because government is saying, “You can't do that anymore. We're going to put up new restrictions to limit tech transfer into China.”

[00:46:39] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Chris Miller. We'll be right back.

[00:46:43] This episode is sponsored in part by BetterHelp. The holidays are among us, the twinkling lights and festive jingles are great, but sometimes beneath it all we feel a pinch of loneliness or stress. Now if there's one thing I've learned over the years, it's that every challenge presents an opportunity. So, let's shake things up with BetterHelp. Think of BetterHelp as your personal GPS through the emotional mazes of life. It's not about finding the fix but having someone to guide you as we navigate our feelings. It's all online, which means no waiting rooms, no awkward encounters in the hallway, certainly no limited hours. With over 30, 000 licensed professional therapists in BetterHelp's network, you're bound to find a fit. But if you don't click, switching is as easy as a reroute on a navigation app. BetterHelp has helped so many people. Check out their five-star reviews on the phone app, solid. Find your bright spot this season with BetterHelp. Visit betterhelp.com/jordan today to get 10 percent off your first month. That's Better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan.

[00:47:33] This episode is also sponsored by NetSuite. As the show grew over the last 16 years, which is crazy to say out loud, so have our processes. We're constantly looking at ways to improve the team's productivity to make things easier for everyone like sending out invoices, updating inventory, or even just keeping track of customer interactions. We try our best not to drown in manual processes. I mean, it's a lifestyle business. We got to improve the lifestyle, right? So, when everyone is doing their own thing, using different platforms or processes, you end up with an organizational mess. Aligning the team becomes like herding cats, and that's where NetSuite comes in to help. So, if you're listening and nodding your head thinking, “Yep, that's me,” you just need to remember three numbers, 36,000, 25, and 1. I remember they were all clever with this. 36,000 represents the number of companies already using NetSuite to revolutionize how they do business. 25 is the number of years NetSuite has been in the game, fine tuning their platform to adapt to changing business needs. And 1 is because your business is one of a kind, a customized solution and one efficient system. Right now, download NetSuite's popular KPI checklist designed to give you consistently excellent performance. Absolutely free at netsuite.com/jordan. That's netsuite.com/jordan to get your own KPI checklist, netsuite.com/jordan. Seriously, we use NetSuite. It's been awesome. It unifies everything into one place. They're almost underselling it here, but that's my personal opinion.

[00:48:47] If you like this episode of the show, and why wouldn't you, I invite you to do what other smart and considerate listeners do, which is take a moment to support our amazing sponsors. They're the ones who keep the lights on around here. All the deals, discount codes, and ways to support the show are at jordanharbinger.com/deals. You can also, email me. I'll dig up a code for you. It really is that important for y'all to use these that I will email it to you. If you're like, “What's the product? It's the bed that gets cool. What was the name?” I will figure that ish out and mail you the code. That's how crucial this stuff is. So, thank you for doing that. Thank you for supporting those who support the show.

[00:49:17] Now for the rest of my conversation with Chris Miller.

[00:49:22] It is a worry that China's a more important customer for chip manufacturing than say the US government just because isn't the market share in China, isn't that so much larger than the chips that say, the United States government purchases?

[00:49:35] So, how do we figure that one out, right? Because it's tough to tell a company, “Hey man, you can't sell smartphone chips to China at all.” I mean, I guess you can do it, but you're really saying you're going to make way less money next year because we don't need as many as China does. And you can't sell to them at all.

[00:49:51] Chris Miller: That's right. I think the way I think of it is Joe Biden's got a lot of power over the chip industry, but Apple CEO Tim Cook has 25 times as much power since he spends 25 times as much money on chips each year as the US government. That's why we've got to have a situation in which US firms have a incentive to keep selling to China, but only less advanced technologies.

[00:50:13] That's what the government's trying to set up right now. They're saying you're most advanced technologies you can't sell, but you're less advanced ones that aren't sensitive keep selling those all you want. Less advanced smartphone chips, PC chips, data center chips, so long as they're not used for AI, keep selling those to China. Not a problem. It's just the cutting edge that we're worried about.

[00:50:28] Jordan Harbinger: How does the United States calculate the risk then of supporting Taiwan, right? We can't just sail aircraft carriers into the Taiwan Strait anymore, I think, because of the types of missiles that China has. Is that correct?

[00:50:41] Chris Miller: It would certainly be a risk.

[00:50:42] Yeah. So, China could then blockade Taiwan. And then what, the US and Japan have to go rescue that? Well, maybe Japan have to go in and rescue them, which could escalate things. I mean, do you have any insight into this based on your research?

[00:50:55] Chris Miller: Well, this is the scariest scenario because if China were to invade outright, I think there's no doubt the US would come to Taiwan's aid. But if China does a blockade, then the onus is on the US President to decide what do you do next? Do you threaten to use the US Navy to break the blockade? Are you willing to shoot first in a blockade scenario? You've only got a limited period of time before Taiwan starts facing huge shortages of energy, maybe even of food.

[00:51:20] It's very difficult to know what a president would do in that scenario.

[00:51:21] Jordan Harbinger: That is quite scary. And I think about this because, you know, I'm taking my family, my wife, and kids to Taiwan to visit their family. And I don't really want to be there when that happens. I'm hoping it never happens. Certainly, that it doesn't happen this October would be, you know, ideal for me personally.

[00:51:38] But it does scare me a little bit. I am taking some solace in the idea that It's going to be just as bad for China if they do this, in terms of semiconductors and not being able to produce anything or run their economy. But I don't know. Are we making a mistake underestimating how irrational a dictator can be?

[00:51:57] Chris Miller: That’s the risk. If Xi Jinping is just trying to maximize Chinese GDP or to make China as wealthy as possible, then he certainly won't touch Taiwan. But that isn't really what's driven him thus far. He had zero COVID for two years, which is economically disastrous. Now he's got the highest youth unemployment China has ever seen since they've been collecting this type of data, and he's pursuing his policies regardless. So, I think we shouldn't assume that he's focused purely on economic maximization.

[00:52:24] Jordan Harbinger: If he does this, if China does this, the losses I'm guessing are going to be measured in the trillions, not the billions or the hundreds of billions, right? This is how long would it take to recoup the ability to manufacture chips elsewhere or recover from this kind of economic damage globally?

[00:52:41] Chris Miller: It would be many, many years. It's the cutting-edge chips that are made in Taiwan, but it's also, tons and tons of mature technology chips as well that are made in Taiwan. So, the amount of capacity that you need to rebuild is just extraordinary. The number of machine tools inside of those factories you need to rebuild is on its own a huge challenge. So, it would be half a decade if not longer.

[00:53:02] Jordan Harbinger: Gosh, okay. What do you think of the war in Ukraine in terms of deterring China from invading Taiwan? I mean, do you think authoritarians are learning a lesson from Putin's disaster here? Or do you think that they're potentially emboldened somehow because maybe they can do it better?

[00:53:16] I don't know. Again, dictators, typically narcissistic, typically don't think things apply to them, et cetera, et cetera. So, I don't know. Where do you stand on this?

[00:53:25] Chris Miller: It's hard to read, but look, Putin still got 20 percent of Ukraine. So, that's not a complete failure. It's not a complete success, but it's not a complete failure.

[00:53:32] Second, Putin has successfully used nuclear threats to stop the US from doing more to help Ukraine. I think there's a direct connection between that and the fact that China is building up its nuclear arsenal very rapidly right now.

[00:53:43] Jordan Harbinger: Sure. Knowing that you can completely drop 90 percent of the supply chain of chips around the world by blockading Taiwan or I don't know, even just blowing up one of the small areas, I mean, you don't even need a conventional invasion to do that.

[00:54:00] They can lob something over there and put a massive dent in the global economy. Yes, they would be poking their own eye, but so what? Dictators don't give a crap if people can't buy things for a while. They care about their economy, but if they cloud the whole thing in patriotism, they might get away with it for at least a little while. It's really hard to say.

[00:54:18] Chris Miller: Yeah. I mean Mao Zedong wasn't known for his skillful economic management, but he held power for a long time.

[00:54:23] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, exactly. He had famines that he'd engineered that killed dozens of millions of people during that time. I mean, it's not inconceivable that they would do something like that by accident or even deliberately.

[00:54:35] That is something that keeps me up at night, really. What about quantum computing? Again, if this is outside your expertise, let me know. But is there a role that that plays in terms of semiconductors? Because I'm guessing you said Moore's Law ends at some point, right, where things double. Do we suddenly go into the quantum realm and it's just a different set of rules and laws?

[00:54:54] Chris Miller: Probably, but it's too soon to tell. Right now, there's a lot of investment in quantum computing, but there's not yet a single practical use case of quantum computing. So, we're just too early in the process to know. I think, one thing that is interesting is that a lot of the paradigms of quantum computing envision quantum right next to very high-powered silicon processing, deep interrelationship between the two, and so, I don't think we should assume that quantum's just going to replace the ingesting paradigm.

[00:55:18] Jordan Harbinger: You write in the book that the world may split between general purpose processing where progress may slow, right? So, that we can't make the thing smaller, and then special purpose processing, which continues to innovate and progress.

[00:55:29] Tell me about that, because it seems like when we make things smaller and we're no longer doubling, fine. Then we just get better at making things specifically for one reason.

[00:55:40] Chris Miller: Yeah. So, for the past 50 years, basically, all progress in computing has been driven by Moore's Law shrinking, which has given us general purpose computing power.

[00:55:48] So, the chip in your computer, it can do your browser, it can do Excel, it can do Microsoft Word, all pretty [unintelligible], and that's great. And so, if you were designing a computer over the last 50 years, you just wait for the next processor to come out. It'd be twice as good, and you get twice as much power. But as Moore's Law gets harder to sustain, there's more incentive to make specialized processors around specialized purposes.

[00:56:12] So, best example is the GPU designed specifically for AI purposes today. It's not good at everything else, but it's really good at AI. And because we've got huge demand for AI right now, there's huge demand for GPUs.

[00:56:24] Jordan Harbinger: GPU, is that not graphics or am I thinking of something completely different?

[00:56:28] Chris Miller: Well, GPUs started as graphics. Initially for computer graphics, that's how they got off the ground. But around, 10, 15 years ago, people began to realize that the same math undergirding graphics is also useful for training AI systems. And so, today, if you look at NVIDIA, most of the growth now is coming from selling GPUs to companies that are training AI systems.

[00:56:48] Jordan Harbinger: They're right next to my house here, and I got to tell you, I was like, “Oh, this poor company, they built this new building, and then there's the pandemic.” And then I looked at the stock, and I was like, “I will shed no tears for this company.” The only tears I'm shedding are me not having bought stock in NVIDIA five years ago when I first thought about it, because they were making new video games that need it. And I thought, “Ah, this is going to taper off.”

[00:57:08] And now we've got AI, and it's just hockey stick growth, so, congrats. If you work at NVIDIA, and you have stock options, my hat is off to you. You have won the lottery in terms of jobs and the economy.

[00:57:19] Tell me about the CHIPS Act, because I've only read a little bit about this. But it seems like the idea here is, okay, all of our eggs are in the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company basket. That's not good to be only all-in on Taiwan or at least, to only have one place that makes these. Let's throw tens of billions of dollars at the United States, generally a good bet, to bet on manufacturing in the US. But is it working or is it too early to tell?

[00:57:45] Chris Miller: It's definitely working in the sense that there's been a huge increase in investment in chipmaking in the US. Lots of different companies investing a lot more than the historical trend. You talked about hockey sticks and NVIDIA. There's been a hockey stick upward in chipmaking investment in the US.

[00:57:58] The question is going to be, after the CHIPS Act money is spent, will those companies keep investing in the US or will it be a one off? And there, it's too soon to tell.

[00:58:08] Jordan Harbinger: I’d love to think that we didn't just waste all of that. I mean, what would stop us from being successful there?