Can music replace drugs? Daniel J. Levitin shows how your favorite songs can release natural opioids, restore memory, and heal neural pathways!

What We Discuss with Daniel J. Levitin:

- Music functions like a Swiss Army knife in the brain, not just a hammer. Different music triggers different neurochemical systems — dopamine for motivation and pleasure, endogenous opioids for pain relief — explaining why personalized music choices are crucial for realizing therapeutic effects.

- The brain’s default mode network can be activated by music, providing a restorative mental break that replenishes depleted glucose levels — like nature’s reset button for our exhausted, decision-fatigued minds.

- Music therapy shows clinical evidence for treating Parkinson’s (by synchronizing movements), memory disorders, and pain management — sometimes reducing or eliminating the need for pharmaceutical interventions through our body’s natural neurochemical responses.

- Musical processing uses different neural pathways than speech, which is why people with speech disorders like stuttering or neurological damage from stroke can often still sing fluently — offering alternative communication channels when primary ones fail.

- You can start your own music medicine cabinet today by creating mood-specific playlists for different needs — and counterintuitively, when feeling depressed, choose songs that match rather than oppose your mood. This validates your emotions and creates a feeling of being understood.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

Ever noticed how a song can transport you back to your first kiss, or how certain beats get you moving even when you’re exhausted? There’s something almost magical about the way music infiltrates our neural circuitry — like a melodic pickpocket, stealing past our logical defenses and tinkering with our biochemistry. While we’ve instinctively used music to pump ourselves up at the gym or calm down after a stressful day, science is now revealing that these aren’t just pleasant psychological tricks. Music operates like a neurological Swiss Army knife, activating alternative pathways in our brains, releasing natural pain-killers, and even helping patients regain abilities that traditional medicine considered lost causes.

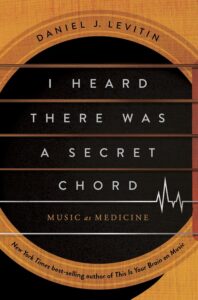

On this episode, we’re rejoined by neuroscientist and I Heard There Was a Secret Chord: Music as Medicine author Daniel J. Levitin to understand the remarkable relationship between music and our brains. Daniel explains how music therapy isn’t pseudoscience but evidence-based medicine that can synchronize movement for Parkinson’s patients, trigger memory in those with dementia, and release our body’s own opioids for pain management. He shares surprising insights about how stutterers (like Elvis Presley) can sing fluently and why listening to sad music when you’re depressed validates your emotional state rather than dismissing it. What makes Daniel’s perspective particularly valuable is his dual expertise as both scientist and musician, allowing him to debunk myths (like the Mozart Effect) while confirming genuine neurological phenomena. Whether you’re a music enthusiast who’ll appreciate the deeper musical terminology or someone simply fascinated by the brain’s remarkable plasticity, this conversation offers a symphony of insights about how those vibrating air molecules might just be the most underutilized medicine in your wellness toolkit. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. We appreciate your support!

- Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini-course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

- Subscribe to our once-a-week Wee Bit Wiser newsletter today and start filling your Wednesdays with wisdom!

- Do you even Reddit, bro? Join us at r/JordanHarbinger!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- NordVPN: Get an exclusive deal at nordvpn.com/jordanharbinger

- IQBAR: Text “Jordan” to 64,000 for 20% off all IQBAR products with free shipping

- Northwest Registered Agent: Get more at northwestregisteredagent.com/jordanfree

- Notion: Try it free at notion.com/jordan

- Airbnb: Find out how much your space is worth at airbnb.com/host

Dive into a world where darkness reigns absolute, yet life thrives in conditions that would pulverize surface dwellers — hinting at what we might discover on alien worlds on episode 1089: Victor Vescovo | Into the Abyss: Reaching Earth’s Deepest Places!

Thanks, Daniel J. Levitin!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- I Heard There Was a Secret Chord: Music as Medicine by Daniel J. Levitin | Amazon

- Listen to Songs Featured in Daniel J. Levitin’s I Heard There Was a Secret Chord | linktr.ee

- Daniel Levitin | Website

- Daniel J. Levitin | How to Think Critically in the Post-Truth Era | Jordan Harbinger

- Daniel Levitin: Why Do Brains Love Music? | Inner Cosmos with David Eagleman

- Charan Ranganath | The Mysteries of Memory and Why We Remember | Jordan Harbinger

- Reconstructing and Deconstructing the Self: Cognitive Mechanisms in Meditation Practice | Cell Press

- 20 Years of the Default Mode Network: A Review and Synthesis | Neuron

- Daniel Pink | When Is the Best Time to Get Things Done? | Jordan Harbinger

- The Dunning–Kruger Effect | The Decision Lab

- Ask the MD: Music Therapy and Parkinson’s | The Michael J. Fox Foundation

- Researchers Use Music to Reduce Shuffling Gait in Parkinson’s Patients | Boston University

- Muting the Mozart Effect | Harvard Gazette

- Pregnancy Music: The Effect on Unborn Babies | Aptaclub

- Nine Tragic Cases of Feral Children Who Were Found in the Wild | ATI

- Cochlear Implants | Mayo Clinic

- Is There Really a Critical Period for Accent Acquisition? | USC Rossier School of Education

- Neuroscience of Music — How Music Enhances Learning Through Neuroplasticity | Neuroscience News

- Research | American Music Therapy Association (AMTA)

- Using Music to Treat Aphasia | The National Aphasia Association

1147: Daniel J. Levitin | The Science Behind Music as Medicine

This transcript is yet untouched by human hands. Please proceed with caution as we sort through what the robots have given us. We appreciate your patience!

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:01] Daniel J. Levitin: There's not two kinds of medicine. There's not Western medicine and alternative medicine. If something's been shown to work, we call it medicine. If it's not been shown to work, there are some people out there who will call it alternative medicine. If we knew that it worked, it would not be an alternative. It would just be plain old medicine.

[00:00:25] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people and turn their wisdom into practical advice that you can use to impact your own life and those around you. Our mission is to help you become a better informed, more critical thinker through long form conversations with a variety of amazing folks, from spies to CEOs, athletes, authors, thinkers, performers, even the occasional mafia, enforcer, fortune 500, CEO, or Hollywood filmmaker.

And if you're new to the show or you're looking for a way to tell your friends about it, and of course I always appreciate it when you do that. I suggest our episode start packs. It's a great place to begin. These are collections of our favorite episodes on topics like persuasion and negotiations, psychology, geopolitics, disinformation, China, North Korea, crime, and cults and more.

That'll help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show. Just visit Jordan harbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started. Today we're talking about music. Hey, normally I'm not that interested in this topic, but as we will learn today, music is not just for jamming and relaxing.

It can actually help your immune system. It can trigger memory even in people with impaired memory or diseases. It can treat other diseases like PTSD and a whole lot more. Daniel Leviton has been on the show before. He has a knack for picking super interesting science topics and then just doing a killer job communicating his research on the show.

If you love music, you'll love this episode. If you love science, you'll love this episode. And if you love science and music, well you do the math. Here we go with Daniel Leviton. I read the whole book, by the way. Really enjoyed it. I think that stuff is just so fascinating. We, as humans, we kind of know music does something because we feel it, right?

When I play music in the gym, I feel like my workouts are a little bit better, a little bit more fun. When I play music, when I'm hiking, I'm less tired for some reason. But no one until recently maybe has really thought about why this happens. And you really do a good deep dive in the book on this. The book starts with this concept of, I think you called it fusion, where your awareness changes when listening to music.

Can you explain this for me? I've never heard of this.

[00:02:28] Daniel J. Levitin: Well, experiential fusion is a term coined by Richard Davidson at University of Wisconsin Madison, who works closely with the Dalai Lama about altered states and meditative states and such. And the idea is that it's sometimes referred to as flow, although it's slightly different, a flow state, you're in the zone if you're a basketball player or if you're a coder, you just lose track of time.

But the experiential fusion that you and I are talking about with music is that under the right circumstances, you forget that you're listening to music. You might even forget who you are. You become one with the experience and the brain basis of this gets to a circuit called the default mode network that my colleague, Vinod Menon discovered.

At Stanford, it is an altered state of consciousness where you're not in control of your thoughts, you're not directing them. They're self and internally directed, and we call it the mind wandering mode. And music can certainly activate that. And it's a healthful and restorative mode to get into, and it's a good antidote or reset button for the kind of hyper caffeinated work schedule many of us follow.

[00:03:43] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, we've talked about the DMN, the default mode network on the show before. This is why I come up with great ideas in the shower mode. Is that right? Exactly right. Yeah. But why do we wanna enter that state besides coming up with great ideas in the shower? You mentioned that it's a restorative time for the brain.

[00:03:58] Daniel J. Levitin: So we talk about paying attention. It's an apt metaphor because attention like money is a limited capacity resource. And the cost of attending to something is metabolic. We use up blood oxygenated glucose in order to attend to things, to focus on things. And every time you make a decision, you're using a little more of that glucose and it gets depleted and you need to take a break.

What many of us do is we'll just have another cup of coffee or something, you know, the bump of caffeine and that doesn't really help the brain. It doesn't replenish the glucose, it just masks the symptoms of us being tired. Yeah. And it kicks the can a little farther down the road and all that. But what you wanna do is then take a break and this gets to the Pomodoro method of work and break cycles

[00:04:54] Jordan Harbinger: is so there, there is something to Mark Zuckerberg wearing the same clothes every day so he doesn't have to make a decision in the morning?

Or do you think that's hyped up?

[00:05:03] Daniel J. Levitin: My favorite example of that is Barack Obama wearing the same clothes every day. But yeah, sure. If you don't have to make that decision, there's a limited number of decisions you can make in a day. And no matter who you are, and there are a number of studies of this, now we're getting a little far a field from the music idea, but there was a study of Israeli court judges and they tended to hand out more arbitrary sentences at the end of the day.

So the message is, if you were gonna appear in court, you wanna be at the early days of the calendar, right? Oh, and you don't want to be right before the lunch

[00:05:35] Jordan Harbinger: break when they're tired. Oh gosh, I remember this study. It's like, if the judge is hungry, you're in trouble, man.

[00:05:42] Daniel J. Levitin: Exactly. They might be feeling hungry for food, but really their brain is hungry for glucose.

The fuel of the brain is glucose and it's what allows neurons to do their work. So you wanna get in the default mode as a way of. Allowing your brain to replenish its own resources, and you can do that in a number of ways. You can go for a walk in nature. You can meditate, you can take a nap. You can listen to music.

[00:06:09] Jordan Harbinger: I can just imagine that, your Honor, I'd like to submit this croissant for you to eat before we proceed here because my client really wants to stay outta prison and you're not you when you're hungry. It's like a Snickers commercial. May I approach the bench, your Honor? Exactly. Do you like grapes or you want an apple?

I brought a a few different items here for you to choose from. Yeah, that's really scary because of course we don't necessarily realize that we're in that state. I assume these Israeli judges weren't thinking like, I'm a real bastard before lunch, so that guy's in trouble. They probably just thought, well, this is how the day goes.

I assume unless you're paying attention, you have somebody studying your decisions, you're not necessarily paying attention to your emotional state. You think you're in the same emotional state while you're at work, until you go home.

[00:06:52] Daniel J. Levitin: And as your thinking becomes cloudy, you have less of an ability to assess your own thinking.

[00:06:57] Jordan Harbinger: Ah, yes. That is a little bit scary, especially the coffee thing.

[00:07:00] Daniel J. Levitin: Well, it's a version of the, uh, Dunning Kruger. Yes. The problem with people who lack intelligence fail in two accounts. One is they make bad decisions, but the other is they're overconfident because they don't realize that they lack the intelligence to make a good decision.

[00:07:18] Jordan Harbinger: Exactly. In many ways, of course, we all think we're above average, but it must in some ways be kind of nice to see the world in this completely black and white way, where you go, it's not complicated. Just do this really obvious thing that I came up with because they don't understand any of the nuances to what's going on in front of me at all.

It seems like yes, your life won't work out the way that you probably want it to, but day to day your existence is probably a hell of a lot easier. I dunno, that's a paradox. I'm always finding myself caught in. Back to music, though, according to your work, it can reduce pain, it can enhance focus, pump you up in the gym.

You mentioned Parkinson's. Patients use it. Tell me about that. Because Parkinson's. Alzheimer's, a lot of this stuff, I have aging parents. I'm also not getting any younger. That stuff freaks me out. It sneaks up on you.

[00:08:03] Daniel J. Levitin: So I would start by saying that music is not a hammer, it's a toolkit. Different kinds of music do different things.

It's not a single tool, it's not a hammer or a wrench or a screwdriver. It's more like a Swiss Army knife. And different music will do different things for you, so you don't wanna lump it all together. So in the case of Parkinson's music that has the tempo, that is more or less your walking speed, your gait will help restore the ability of Parkinson's patients to walk.

When they've lost that ability due to degradation of circuits in the basal ganglia and other regions that control smooth continuous movement, Parkinson's patients often freeze. There's an internal clock or timer that allows them to time their steps. It's like a metronome. When that's degraded. If you play the music, we now know there are populations of millions of neurons that synchronize to the beat of the music, and that becomes an external stimulus for them to guide their movements and they can walk just fine.

Now you use the term metronome and the interesting thing is a metronome doesn't work as well as music and it, I think it's because music is a lot more engaging than a metronome, probably.

[00:09:16] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Than just the tick, tick, tick. For those who don't know that metronome is what, essentially a pendulum that makes a ticking sound.

Yep. Do the Parkinson's patients walk faster? If you play music with a faster BPM. So the

[00:09:28] Daniel J. Levitin: trick there is to get it at their normal gate, otherwise you become unsteady and could fall. Sure. But it's the same principle why we see Olympic athletes, especially runners and marathoners running with AirPods to music that's at one or two beats per minute faster than they normally would run.

Then they can synchronize to that slightly faster beat and actually increase their running times.

[00:09:53] Jordan Harbinger: So I wonder if each runner would have their track that is probably at the exact max they can go. Maybe it warms up a little at the beginning. I don't know anything about running, but I assume they start sprinting as fast as they can, but as their brain and everything gets synced up, they can probably pick up speed a little bit during the sprint.

I really don't know. That's fascinating. I actually never noticed that those people were wearing AirPods or earbuds at all. I guess during training they are. Yeah. Oh, I see. So during a match they're not doing this.

[00:10:20] Daniel J. Levitin: I don't think so. But I'm sure some of your million listeners will write in now and be very angry.

[00:10:25] Jordan Harbinger: Yes. It always happens. Someone's gonna write in and say, Hey, I've ran in the Olympics and I was not allowed to wear AirPods or something like that.

[00:10:33] Daniel J. Levitin: I've seen people train with them. That makes sense.

[00:10:35] Jordan Harbinger: I just assume people train with music because it's more fun to train when you're listening to music than it is to spend an hour in dead silence while you're sweating in the sun.

It's a tool that I don't know, I'm using.

[00:10:45] Daniel J. Levitin: Fun is important here. If you've got an exercise workout that's otherwise unpleasant or painful, we know that music can act as an analgesic, a natural painkiller, and it can act as a motivator. So these are two different tools in the Swiss Army knife of music and two different neurochemical systems.

The fun of music is driven by the dopaminergic system. Listening to music you like releases dopamine. Our lab was the first to show the analgesic painkilling effects. If you listen to music, your brain releases its own endogenous. That is internal opioids. So where you might otherwise be weightlifting or running and feeling some pain, the music raises your pain threshold, so that doesn't bother you

[00:11:31] Jordan Harbinger: anymore.

I love that. And what I find fascinating about this is some people are going, well, what kind of music? And I assume, let's say the Parkinson's patients. They could probably listen to anything 'cause they're syncing up their steps. But I assume older people wanna listen to, I don't know, Elvis or something like that.

Younger people wanna listen to different things. Like Taylor Swift, whenever I go to the gym with friends, it's always like one guy brings a Bluetooth speaker and I'm like, God, do I have to listen to what you're listening to? Because he gets stoked for it. And I put my noise canceling headphones in and I have to turn the volume up 'cause I want slightly different music.

So I guess my question is, this has to be music that we choose, that we like, right? It can't just be there is music in general playing and it all has the same effect on everyone. The person who loves Elvis is probably gonna have a better effect than the person who likes EDM but is subjected to Elvis. Is that accurate?

Absolutely.

[00:12:22] Daniel J. Levitin: You're the A student. Yet again, it has to be music you like and you can't say, oh well classical is better, or Elvis is king and he's better than Billie Eilish. We can leave that argument to musicologists, but if you're talking about brain effects, what your brain cares about is what it likes.

And so for a Parkinson's patient, if the tempo's right, it could be heavy metal or country or tube and throat singing, none of that matters. And same with a exercise workout or pain killing. And so we don't think of it in terms of genre of music or artists. Mozart is not special. Sorry to burst the bubble.

That whole Mozart effect was bad pseudoscience.

[00:13:05] Jordan Harbinger: What was that that, is that the baby thing where it's like, you gotta play this to your baby and they come out smarter? Is that what you're talking about? Yeah. That's not true. But what do babies hear in the womb? Do we know that?

[00:13:18] Daniel J. Levitin: Yeah, we do. By the age of 20 weeks, the auditory system of the developing fetus is fully functional.

They hear through amniotic fluid, which is somewhat like for us to listen under water. If you're at a pool and there's music blasting, you'll notice here mostly the low frequencies, the notes, the percussion, the infant brain is wiring itself up to the sounds that it heard in the womb. Suppose you could say it's a womb with a view.

Uh uh. How do you use it? In every interview or we special? No, you're special. Thank you. It's funny, they're wearing themselves up to the base notes and to the rhythms, and there was a very clever experiment done by Alexandra Lamont in England many years ago where she had expectant mothers play music to their unborn children.

And then a year later she came back and played tracks from those same albums to the now one year olds, a year and three months later, let's say. And some of the tracks she played were ones they had heard. Some of 'em were by the same artists that they hadn't heard. And the 1-year-old showed a marked preference for the music they had heard in the womb and not heard since.

Really? That's

[00:14:27] Jordan Harbinger: interesting. That is shocking. I suppose just because the idea that the baby would internalize that, remember that at some level from being just in utero when they can only hear the underwater version. Now they're hearing the higher fidelity version. It's quite amazing because the time in the brain development and the fact that it would've sounded totally different, they still had a preference for that same track is crazy.

Actually. Really impressive. Brains are impressive and that's one of the reasons why we do so many shows about the brain is the more I learn about the brain, the more I'm just like, okay, we were designed by aliens or something. This is just too incredible. Is there a cutoff for learning in neuroplasticity for kids?

I know this is not directly on topic. The whole language thing, like if you don't learn it when you're a kid, you're never gonna learn it and all that stuff.

[00:15:15] Daniel J. Levitin: There's a phrase in developmental psychology called critical period, and that refers to a kind of a hard stop. If you don't learn something by a certain point, you'll never learn it.

And language and music are not like that. They're more like a sensitive period. They're a statistical distribution, meaning that most people have to learn some kind of language before a certain age or they never learn to speak. There've been these unfortunate, tragic events where a baby was locked in a closet.

Yeah. Or feral children. Yeah, exactly right. And if you don't learn to speak before, I mean, there are arguments about what age it is, but let's say it's eight to 10 and you're finally rescued and they try to teach you language, that window has closed. You'll never learn to speak in complete sentences. I'm not a develop neuropsychologist.

It might be six to 10, but it's a hard stop. But we see it in our own lives in a more gentle way, which is that if you try to learn a foreign language before the age of say 14, give or take a couple of years, you might very well learn to speak it without an accent and to become fluent just by osmosis, just by hearing it spoken in the home, we have lots of cases of bilinguals, trilinguals, multilingual kids who grew up in a multi-generational household speaking five languages, and they're equally fluent in all five.

By age 10, let's say, there's no additional cost for having learned more than one language. But if you and I were to try to learn Japanese right now at our age, it would be a whole lot of work and we might be able to at some point speak like a diplomat, which is what our ambassadorial service do. I mean, they send 'em to these training camps.

So they can become ambassadors to countries where they don't speak the language, but they'll always speak with an accent. The accent has to be within this sensitive window. And the same is true with music. If you don't hear music before a certain age, you're never gonna understand it. Oh

[00:17:13] Jordan Harbinger: wow. That's fascinating.

But that would be hard to test. Good luck finding a kid that hasn't heard music, although I guess feral children haven't heard music. Haven't heard a language or deaf children. Oh, deaf. Yes. Who suddenly have their hearing

[00:17:24] Daniel J. Levitin: restored.

[00:17:25] Jordan Harbinger: That makes sense. Duh. Cochlear implant or something that makes way more sense and is way less sad.

The opposite. The cochlear implant thing is actually like a miraculous piece of technology. Do you know how they work? Because I'm always mystified to how this thing on the outside of your head just tells your brain what you're here. It's like a fake ear. It's just amazing.

[00:17:43] Daniel J. Levitin: Cochlear implants have to be implanted early.

I. They have rather mixed results for adults who go deaf. But what's happening is the way the ear works is your eardrum vibrates in and out and that causes activity inside a structure that's coiled up like a snail shell called the cochlea. And there are hair cells neurons that fire along if you were to unwrap that thing and make it flat at one end of it, there are neurons that respond to low frequencies and the other end high frequencies, and it's sort of laid out like a piano keyboard.

And when a, a high frequency like comes in, this one vibrates. And if it's a low frequency like this one vibrates and they send electrochemical messages on up to the brain, if that whole apparatus isn't working, but the brain is still working, what they do is they implant electrodes in the brain to receive signals from an external microphone type thing that's inside the ear canal.

The problem is that your actual brain has tens of thousands of these neurons, and we can implant a couple of dozen of these little electrodes, and so the voices and the music you hear are not very high resolution. They're like a super bad MP three. You're hearing from a distance with white noise embedded over it.

[00:19:08] Jordan Harbinger: I see. So it's better than not being able to hear it all because you can hear the car honking or the people talking to you, which is life changing, but you're not suddenly going to be able to hear like you or I through these earbuds getting a cochlear implant with today's technology. Right. Yeah. Okay.

That makes sense. 'cause I was just like, you just put wires in the brain and the brain goes, I know what to do with these. I mean, that to me is still amazing, frankly. Now back to language learning. I speak several foreign languages, none of which I learned as a child. I learned them all after the age of 17.

I think. German, Spanish, Serbian, Mandarin, Chinese in an English, and uh, Alma. Yeah. Yes, Al. So the language thing is it drives me nuts because I can hear my accent, especially in German where I'm the most fluent and there's almost kind of nothing I can do about it. I'm very good at imitating voices. I'm very good at imitating accents, doing video game voice characters.

I just can't get every single nuanced syllable in a German word unless I practice each one over and over and over and over again. And then when I say them fast in different combination, it just falls apart. But then there'll be a kid who had a German nanny growing up and is taking German in college, and I'm like, oh, you bastard.

You sound better than me even though your vocabulary is a 10th of mine. And so there's definitely something to that. I've been studying Mandarin for about a dozen years. I can read and write, and one of my friends said, no matter how long you study this, people will be able to tell that you're not Chinese.

And I, I had to laugh because I'm pretty sure it's not merely the language proficiency that's gonna give me away as somebody who's not Chinese. But it's just, yeah, you're right. There's this sort of impossible barrier that you just can't cross. My son can speak Mandarin really well. My daughter can understand Mandarin really, really well, Spanish as well, and they will have a much easier time, I think, becoming fluent and possibly accent free in those languages just because we've started them so early.

I grew up in Michigan. Nobody spoke of foreign language in my house or near me anywhere, pretty much. Maybe some Arabic or something like that in Persian, but not in my home. It's amazing though that your brain can still learn it, but it just can't mimic it perfectly, which it's almost like the physical control that your brain has over your ability to speak, it degrades somehow or cuts off somehow.

That's the part I don't totally understand because I can still dream in German. I can still think of things completely in German. I can still construct grammatically perfect German sentences. I just can't say the damn words in the way that Germans do.

[00:21:44] Daniel J. Levitin: You could work as actors do with a speech coach.

Sure. And you could learn to do a much, much better job. And some diplomats, if they need to, they get this training. It's very intensive. Takes a lot of work. Things that would've come effortlessly to you as an 8-year-old are gonna be a lot of work. It's not impossible, and you can get pretty darn good. I think that a real native speaker will still notice just in the way that you as a Michigan or.

Somebody in New York will probably predict. You're from the Midwest.

[00:22:15] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. They always say Canada. But yeah, it's basically,

[00:22:18] Daniel J. Levitin: I mean, there's a little subtle thing about the vowels. I have a weird accent because I spent 40 years in California, but 20 years in Canada. Oh yeah. And I used to have the neutral broadcaster, San Francisco accent, which was the Canon American accent that all the broadcasters wanted.

I was born into that, but 20 years of Canada ruined it. And people say people can hear it. You can train and get so much better that it would be that subtle. What's happening though in the brain is that in the early years of life, the primary mission of the brain is to learn as much as it can about the environment it's in, because it doesn't know what it's going to need.

So at the age of four, a toddler can learn any of the world's languages. It doesn't matter which country they were born in, doesn't matter what their genetics is, and they can learn it natively. And so let's talk about the Japanese RL distinction. Japanese don't make that distinction. We do. In certain Indian dialects, they have a different D.

There's a fronto dental D, so they wouldn't say deli as in new deli. They would say, deli, new deli. I can make it. I can't really hear the difference. I learned to make it in French. We've got all these different ooh sounds. There's ooh and there's ooh. And they mean different words. If I say I'm getting a book, or I'm getting a book.

It just sounds like I'm saying book with an accent, but in French it would be something very different. Two versus two different words. Different meaning, yeah. Chinese has this because they have tones, they all mean different things. One of 'em means mother, another means lamp, another means gunpowder. Yeah.

But to us it's the same sound so the infant can learn at all. But a funny thing happens around age 10. The primary mission of the brain shifts to get rid of all that unused capacity to make room for other stuff. And so it starts pruning out unused connections.

[00:24:20] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that's such a bummer. But it makes perfect sense, right?

Because the child's brain doesn't know where it is, and the environment, as you mentioned, doesn't know what it's gonna need, right? So it says, okay, maybe I need really sharp hearing because that's what we're doing here. I need to learn this language. I need to be able to decipher this kind of communication.

And I suppose that makes sense why young kids who are born into traumatic or unstable environments suffer so much throughout their lives, right? Because they essentially prune. A lot of neurons that they probably would've needed to, I don't know, go to college and be a successful doctor, but they retain a lot of qualities that keep them safe or alive in an environment where people are doing drugs or there's violence around them, or they don't get food regularly or something like that.

What ages does that sort of stop happening? Do we know? Did you tell me this already?

[00:25:10] Daniel J. Levitin: It's

[00:25:10] Jordan Harbinger: variable, but say 10 to 14. Okay, so it's similar to the whole language thing A as well. Discounts on the fine products and services that support this show. Music to my ears. We'll be right back. This episode is sponsored in part by Nord, VPN.

If you're online without a VPN, you're exposing yourself and not in the fun way. We've been using Nord VP n for years, and in today's world, VPNs are not optional anymore. Every time we travel, whether it was China, Europe, wherever, nor has actually been a total lifesaver in China. It actually just kept us connected and protected when basically nothing else worked.

Airports, sketchy. Cafe, wifi. It's not just hackers. You need to worry about your own internet provider could be selling your browsing data to whoever is paying. I mean, they are doing that. Plus, Nords got the extra perks. You can switch your virtual location in seconds, which means unlocking sporting events, TV shows, movies you can't even get here.

Uh, friends have used it for dating to turn on Tinder and other countries. That's a creative use of that. You can even save money by booking flights in hotels too, because airlines and booking sites use dynamic pricing based on IP address, and I gotta figure that one out, nor it is fast. No buffering, no lag.

On top of that, the threat protection feature blocks, malware, phishing attempts, all the garbage you don't even see coming before it hits your devices. All of this for about the price of a fancy coffee each month, and you can protect up to 10 devices, phones, laptops, tablets, your whole digital life locked down.

[00:26:30] Jen Harbinger: To get the best discount off your Nord VPN plan, go to nord vpn.com/jordan harbinger. Our link will also give you four extra months on the two year plan. There's no risk with Nords 30 day money back guarantee. The link is in the podcast episode description box.

[00:26:43] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by IQ Bar, something I literally just ate.

IQ Mix is a zero sugar drink mix from IQ Bar, that hydrates booster mood and promotes mental clarity. Anyone who knows me knows staying hydrated kind of a thing. Really boring thing to have, but whatever. Not as boring as plain water. And when you're out there rucking seven miles in the hot sun with a 60 pound pack strapped to your back.

Yes, that's a flex. Just drinking water isn't enough to put you back together. That's where IQ mix from IQ Bar comes in. It's a zero sugar drink mix loaded with three times the electrolytes of your average sports drink. It's what plants crave. None of the junk, no sugar, no gluten, no soy, no GMOs. It's even vegan and kosher.

For those of you keeping score, my go-to flavors, pina colada, but they've also got passion fruit, lemon, lime, peach, mango, pink lemonade, raspberry, lemonade. All of those are actually quite good. But IQ mix is not just about tasting better, it's about performing better. It's packed with magnesium L three and eight, which I take a ton of lion's mane, so you get clean energy, real mental clarity without hammering down four coffees.

That's my usual method if I'm a hundred percent honest. No surprise. They've got over 20,005 star reviews.

[00:27:43] Jen Harbinger: Right now IQ Bar is offering our special podcast listeners, 20 person off all IQ bar products. Plus get free shipping to get your 20 person off text Jordan to 64,000 text J-O-R-D-A-N to 64,000.

That's Jordan to 64,000. Message and data rates may apply. C terms for details.

[00:28:02] Jordan Harbinger: If you're wondering how I managed to book all these great authors, thinkers, researchers, scientists, creators, every single week, it is because of my network, the circle of people I know, like and trust. I'm teaching you how to build the same thing for yourself over@sixminutenetworking.com.

This is a course, it's a free course. It's not a schmoozey course. There's no upsells in the course. It won't make you or other people cringe when you use the tactics. It's very practical. A few minutes a day is all it takes. Many of the guests on the show subscribe and contribute to this course, so come on and join us.

You'll be in smart company where you belong. You can find it again, it's free. No tricky stuff. Six minute networking.com. All right, back to Daniel Leviton. I'd love to talk about music and pain relief because the pain relieving effect of music is fascinating. You touched on this earlier, but if we're listening to music and it can help with pain, can it help with not just workout pain, the burn and the muscle?

I just had back surgery. Now I'm an Oxycontin. Do I need less Oxycontin if I'm playing some good jams? Probably. Really?

[00:29:01] Daniel J. Levitin: Yes. You may not need Oxycontin at all. That would be great. Depending on how bad the pain is, you might need Tylenol or ibuprofen, Advil. The brain releases its own opiates in smaller amounts than pharmaceutical levels.

That has to be music you like. One thing that music can do, again, it's a Swiss Army knife. Different music may will relieve pain for you. Then we'll relieve anxiety. But a lot of times pain is exacerbated by anxiety or stress. We become more sensitive to it. The mechanisms are still being worked out, but they're at a sufficient point that I wrote my new book, I heard there was a secret chord links in the show notes in the uk.

It's called Music as Medicine, but it's the same book, different title. I wrote it now because I've been working with the National Institutes of Health and the White House Science Office for 10 years. And there really is a body of literature that not only shows that all these things work, but something in the underlying mechanisms.

We can talk about the neurochemical signaling, we can talk about the brain, the biology of the brain that's involved. And we've seen clinical studies, randomized controlled clinical trials like you would with a new drug where music really can work. But again, not in every case. A friend of mine just got a terrible gastrointestinal infection from eating bad food in Pakistan.

Oh my gosh, that sounds horrific. So it goes to the doctor when he gets back. It was awful. The doctor says, oh, we'll take the antibiotic. He's had to take five different antibiotics, you know, and if you get strep throat, they'll give you an antibiotic. It doesn't always work. So medicine doesn't always work and music doesn't either.

It's a trial and error, but I'm mentioning it because it's not like some wonder drug that's gonna solve all our problems on the one hand, but on the other hand. It's about the same as other drugs. Sometimes they work, sometimes

[00:30:55] Jordan Harbinger: they don't. Is there an addiction treatment angle for people who are hooked on things like opioids?

Can we use music and addiction programs to help this, or is it just that by the time you're addicted to Oxycontin, what the body produces is not gonna ever be enough?

[00:31:13] Daniel J. Levitin: Music is a part of a lot of addiction recovery centers now, whether it's AA or Narcotics Anonymous or various treatment programs. Yes, music is a part of this, and it's a part of it for different reasons.

It's not just the release of endogenous opioids, but the dopamine that motivates you to want to get better and follow healthful practices.

[00:31:35] Jordan Harbinger: I know that shamans and medicine people throughout history, throughout the ages have used music as part of ceremonies, as part of healing. I. Did you manage to research that at all?

I mean, it seems like an obvious connection. They obviously knew music did something back then, and maybe some of it was just to show how serious the ceremony was. But from what I've heard from friends, when you do something like psychedelics or some sort of medicine journey, there's a lot of music and drums and banging and things that go along with some of these ceremonies, and they're there for a reason.

[00:32:06] Daniel J. Levitin: So you're asking the question that any serious scientist would ask. How do you fractionate out the effects of the music versus the dance and the community? If you could assign a percentage, how much is attributed to the music per se, versus these other Paramus aspects? And it's hard to say. It's very hard to come up with a controlled experiment.

So in the shamanistic tradition, either contemporarily or 20 or 40,000 years ago, it was almost always the case that there was a large group of people. There was a leader, the faith healer, who was a very revered person in the community who had special knowledge and special skills. There were often herbal supplements of one kind or another, and the dancing and the community, and it would go on for hours.

They were typically trance states induced. So we try to do these experiments where we'll give people music or not music, and we'll give it to them with dance or not dance, but what's a control for dance that involves body movement that isn't dancing. What's the control for a large group of people that are really pulling for you to bring a bunch of your enemies together and have them sing songs that they, you know, ding Dong The Witch is Dead.

Get Outta here. It's very complicated to partition these out, but the fact is that the way we use music now in clinics and VA hospitals and even for self remedy is that just listening or playing seems to have a substantial and statistically significant effect.

[00:33:42] Jordan Harbinger: That's really good news and very fascinating.

I do wanna separate the sound healing from what we're talking about right now. I wanna separate music and therapy from nonsense pseudoscience like this bowl produces a frequency that will shrink your tumor. Can we do that briefly?

[00:34:00] Daniel J. Levitin: Yeah. So I'm a scientist as well as a musician, and when I'm wearing my scientist hat, I just wanna see what the data have to say and I go in with no preconceptions.

The data are there to tell a story. My job is to figure out what the story is. My job is also not to be distracted by shiny things and stories that don't fit the data. So I've been part of sound baths and I've been to particular sound baths that play Tibetan bowls or crystal alchemy glass bowls, and they're very emotionally moving.

I agree. Spiritually moving. I have a friend named Gerald Glass who runs a therapy practice. She has a company called Crystal Cadence. I brought her to perform in front of directors from, I think there's 27 institutes of the National Institutes of Health. A year ago, the director of the NIH was there and a lot of scientists, and I would say.

All of us were very moved. Now, if you ask her what she's doing, she'll say, well, and I'm gonna get this wrong. This bowl is tuned to C sharp, and so it's supposed to lift your mood. And this B flat bowl is for treating this and that. And the a bowl that's made out of this particular crushed gemstone thing is supposed to treat anxiety.

I don't believe that any of that's true. I also don't believe that when a great pianist like Horowitz or Keine or Alicia de Rocha or whoever it is, when they're playing a difficult piece, you'll see them do this.

[00:35:39] Jordan Harbinger: They're waving the hand in front of the face. Yeah. For people who aren't watching, they're waving the hand off to the side in the circular motion.

[00:35:45] Daniel J. Levitin: So after they release a note, their hand will sort of go off into the air in some grand gesture. Now, the physics of the piano is that once your fingers have hit the keys. The way you release it has no impact on the sound at all. And what you do with your hand after has nothing to do with it, but maybe it has something to do with the mood they're in or the embodiment of the emotion or something.

But I think it's mostly for the audience's benefit. Sure. That they do these grand gestures with their hands. They can believe anything they want to believe. I've met really wonderful musicians who think that the music is in their fingers. I. Not in their brains. And I have to say, well, if we scoop your brain out of your head, you're not gonna be able to play anymore.

And they say, oh, yes, I would because it's in my fingers. I say, no, you wouldn't. I can't believe they argue with you on this. It's a bold argument. I play music. I work with musicians who are brilliant and I don't wanna say anything that's going to interfere with their process. Sure. How they get there in a way that will move me and make me remember a performance for 40 years, or transform my mood for a week or more.

I don't care how they get there. And so when we're talking about the bowls, if a bowl player believes that this frequency is gonna have that effect, whether it has that effect on me or not, it's having some effect. But I do wanna say there is no science at all that says that particular frequencies are associated with particular mood states or particular therapeutic things.

And there's this whole pseudoscientific. Nonsense about how you have to listen to 438 Hertz tuned music instead of 440 or 4 32. It's a magic number. And if you look at 4 32 and you multiply it, it's the distance between here and the moon and it's the number of seconds that it takes the earth to revolve around the sun and it's the heartbeat of your cells or some nonsense.

It's no, it's none of those things.

[00:37:46] Jordan Harbinger: I also don't have a problem with going to a Tibetan sound bath with a group of friends after we went on a hike. We did this recently, I was in Laos and it was like, oh, this person's gonna play the bowl. I. It was relaxing. I slept well afterwards. Might have slept well anyway, 'cause I hiked all day, but it doesn't matter.

The only beef I have with this stuff is where people go, you don't need harmful drugs. That's western medicine. Or you don't need big pharma to pump you full of chemotherapy. You just need to listen to this sound and it will help you. That is where this stuff gets dangerous. When people stop looking for real, he cures or get confused between what is actually effective medicine for a thing that can kill them or hurt them.

That's where I sort of have to draw the line. I'm not trying to reign on people's parade because they have a. Brass bowl in their living room that has a little thing that they like to do in the evening that's harmless. It's a fun hobby. Go for it.

[00:38:42] Daniel J. Levitin: But if you're gonna use that as a cure for cancer instead of using medicine, you and I talked about this eight years ago or so when we were talking about my book, A Field Guide to Lies, and I remember the conversation and my recollection is that we talked about, and I think you were provoking me by using the term Western medicine.

Sure. There's not two kinds of medicine. There's not Western medicine and alternative medicine. There's just medicine. If something's been shown to work, we call it medicine. If it's not been shown to work, there are some people out there who will call it alternative medicine, but it's not an alternative.

If we knew that it worked, it would not be an alternative. It would just be plain old medicine. So this is what killed Steve Jobs. Yes. Steve Jobs got pancreatic cancer and he went to this charlatan named Dean Ornish. Who said, oh, I can fix that with yoga and diet. And maybe there were bowls involved, I don't know.

And you know, it killed him. He was gonna die anyway. But he put all his faith in this weird thing and when he changed his mind and saw it wasn't working, it was way too late for him to use actual treatments.

[00:39:50] Jordan Harbinger: Did he have a really bad prognosis? Because I swear I read somewhere that he had a very treatable cancer initially and it just spread because he didn't do anything real to treat it.

[00:40:00] Daniel J. Levitin: I haven't looked into this in 10 years, but I know that he didn't like what the doctors told him.

[00:40:06] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:40:06] Daniel J. Levitin: That makes sense. So he found another doctor?

[00:40:10] Jordan Harbinger: Yes. Air quotes.

[00:40:11] Daniel J. Levitin: Who told him what he wanted to hear?

[00:40:14] Jordan Harbinger: Oh,

[00:40:14] Daniel J. Levitin: dangerous.

[00:40:15] Jordan Harbinger: Dangerous. Tell me about music and memories. I find that I will listen to a song and immediately be transported back to a time where, I don't know, maybe that song was popular when I lived in Germany, or maybe it was popular when I went to my high school prom or something like that.

And you get those feelings come back, they come rushing back. That's why so many couples have a song, things like that. Is music generally anchored somehow to memories?

[00:40:45] Daniel J. Levitin: Very much so. Not all music, but music that's associated with a particular time and place. And this is what Marcel Proust was writing about when he wrote about the madeleines, the cookies, or what we write about with smells, particular odors.

If there's an odor that's ubiquitous and familiar to you and part of your life every day, that won't do anything, but every once in a while you get a whiff. My grandmother used a very particular soap. I associated that smell with her. And when she died, she had two or three unused bars of this soap, and she died in 1987.

And I would use the soap now and then, and it would instantly bring back a flood of memories of what she was like and what it was like to be with her. And it's because our senses are a trigger for memories, and most everything that you've experienced is in your memory system somewhere. The trick is to pull it out from all the things that are in there.

And so you need something unique. The nature of music, at least in the last 60 years or so, is that we have popular music, we have songs that get played a lot for a relatively short period of time. Oh yeah. And happy Birthday in the national anthem, things like that, where you hear them all the time, they can invoke certain memories.

They're less likely to than that song you heard the summer you were 13, or the song that was playing when you had your first kiss or the song that was playing in that new country you were living in. Those get attached to the memories and all the sight and sounds and people and events are attached.

Memory is multifactorial. It's pictures, it sounds, it smells, it's tastes, it's touch. Does it work for bad

[00:42:35] Jordan Harbinger: things as well as, oh, I remember this song. I loved it. We used to play it in college and go cruise around in the car and meet girls. Does it also function for bad things? Can you hear a song and you're like, oh, this is when my parents got divorced.

This song was on the radio. Yeah. Yeah,

[00:42:50] Daniel J. Levitin: absolutely. It absolutely works for that. And a lot of people who have had traumas, if there was music playing or a sound. A non-musical sound, the trauma can be re invoked or relived or experienced through the sound. This is why soldiers who come back from the war with PTSD for car backfires, they duck for cover instinctively, and it can put them in a hypervigilant and traumatized state for days or weeks or years that they can't escape from just ordinary environmental noises.

The wrong song comes on. Same thing.

[00:43:27] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. One of my earlier memories that I'll never forget, 'cause I'd never seen anything like this. A friend's dad was driving us to lacrosse practice. This is sometime in the early nineties, and we were stopped at a red light and the cars behind us started to honk. And my friend was like, dad go And he froze and he goes, you guys hear that?

And we were like, yeah, the horns. And he goes, no, you guys hear that he had been in Vietnam and he got so triggered by this helicopter that was quite loud and it was low. So it was really extra loud and he just froze. He forgot like where he was seemingly, he didn't know anything about what was going on in that particular moment.

I emailed my friend about this and I said, do you remember that? And he goes, that definitely checks out as something that would've happened with my dad. So that was really disturbing. Well, of course, in a

[00:44:16] Daniel J. Levitin: dangerous zone, a low helicopter can mean the matter of life or death. It could be somebody coming to rescue you.

It could be somebody coming to kill you, and you have to freeze and take an assessment of the situation that really could kill you. And that moment, it's so horrible, the decision you have to make. Do I run towards it? Do I run away from it? Is this friendly or is this enemy, it can be paralyzing.

[00:44:45] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that was one of those things where I just remember looking at my friend and being like, what the hell dude?

And he was just like, I don't know, whatever. And I remember his mom drove us the next time and we were like, what was that about? And she was like, oh. Yeah, something about Vietnam and it happens. It's very rare, but he never drove us to the cross practice again. I have a feeling of when I told my parents, they were probably like, look, they're not letting my kid in the car with you.

I mean, I feel bad for him. Obviously this is something that affected him deeply, but I just found that to be so strange and it makes sense that the trauma and that sound are linked. I hope he's in a better place now 'cause helicopters are everywhere. Alright, if music can do all of this can help us recall good memories, bad memories, help us calm down, help us get amped up.

If music can do all that, why doesn't Spotify take my heart rate and physiological stress levels from my Apple Watch or my aura ring and suggest something to calm me down or to help my workout get better? I feel like Daniel Eck needs to get on this. They will. They are working on it. Are they

[00:45:44] Daniel J. Levitin: okay? And Apple has Apple music.

That makes sense. In the foreseeable future, you will be able to opt in to letting the streaming service you listen to music on. Communicate with your aura ring or your smartwatch, your smart device, and maybe it'll alert you and say, Hey, your blood pressure's getting a little high. Would you like me to play you relaxing music?

Or maybe you'll opt into the automatic whether you want it to or not. It'll start playing you relaxing music to lower your heart rate. And we know there is music that can do that in general for most people most of the time. But we also know there's music that does it particularly for you. They already know this, I'm sure, or could know it if they wanted to, because many of us have these devices that are monitoring.

So I imagine a world in which music as medicine becomes invisible to us, oh, you're on your way to the gym. The GPS knows you're on the way to the gym. It knows from past activity that you're about to get on the treadmill. It also knows that that cup of coffee you had this morning didn't really do the trick.

You're a little bit sleepy, and so it'll play you AC DC or Van Halen or whatever, pumps you up in the car on the way to the gym. And then you get there and it'll keep playing it. You've had a fight with somebody and it'll know what music will calm you and the horizon. And we haven't used the two letters AI yet.

I think what AI can do for us here is whatever music might be relaxing to you today may not always relax you all the time because your brain is constantly changing different events and different physiological occurrences can lead you to have different kinds of anxiety, let's say. And so ideally what AI would do is it would start with a tried and true.

This always calms Jordan down. Monitor in real time, whether it's actually calming you down and if it's not, it would get something else from your playlist or there are now 200 million songs across all the streaming services. It would find something you haven't heard that could become your new go-to thing and test it in real time.

See whether your body really reacts.

[00:48:01] Jordan Harbinger: Seems like AI could actually just make music that it knows I will like in that moment. Probably could. Yeah. That'll be interesting. I think it's quite fascinating that music therapy is not only effective because let's say it's pleasurable, it actually is doing something in the brain.

You mentioned the immune system in the book you mentioned that music discovery can affect our immune system. What's going on with music discovery and our immune system? Why would we even evolve something like that? That ability, the why question with evolution is always tricky.

[00:48:30] Daniel J. Levitin: We know that music can affect the immune system in several ways.

Listening to pleasurable music can increase levels of immunoglobulin A, an important antibody that travels to the site of mucosal infections and help fights them off. We know that music that is pleasurable to you can increase the production of natural killer cells and T cells. Also important for fighting disease and infection.

Some music can lead to reductions in inflammation. Why music does this and why the immune system responds to it, we don't know, but it does. And so evolutionary reason, my guess, is that we evolved over tens of thousands of years with music, and music co-evolved with us so that the kinds of music we made and gravitated towards.

Was the kind of music that made us feel good and was a sort of iterative process where one changes and the other changes in response

[00:49:34] Jordan Harbinger: to it. So they co-evolved. I mean, music is ancient. I suppose it makes some sense. It just is sort of mystifying to me why we would integrate that. So music so thoroughly into our brains, I just don't understand.

And I suppose we, maybe we never will. I've heard people who stutter normally don't always stutter when singing. What's going on here?

[00:49:57] Daniel J. Levitin: So stuttering like Parkinson's is a motor disorder. It's a failure to regulate movements in a particular order and at a particular time, people who stutter are unable to get the words out in the right order and at the right time.

The thing about music is that it has its own intrinsic tempo to it language. Normal spoken language doesn't. We sort of say things the way we want when we want, but when we're singing, there's a time when the word has to come. And so if you can sing and not have any disfluency, it's because of music's internal clock that carries you along with it.

So Elvis Presley, who we talked about earlier, was famously a stutterer. When he spoke, he didn't stutter. When he sang, he also acted, but he probably, when he was acting, memorized the script with a certain cadence. James Earl Jones, the actor, is very disfluent and stutters when he gives interviews, but when he's in a role like in Star Wars where many of the other great roles he had, he has to be able to memorize the script with a cadence and work out ahead of time what the rhythm will be.

And once he does that, these rhythmic circuits in the brain, which are separate from the language circuits take over, they effectively hijack the speech system.

[00:51:21] Jordan Harbinger: And you're in the music mode. It seems like a miracle in me. My mom is a speech therapist. I know teaching people how to manage a stutter is very tricky.

It doesn't always stick. It's easier when their kids, going back to what we discussed earlier in the show, so this seems like a really good insight into how to get around something like that or manage something like that. What about Tourettes? You mentioned this in the book as well, is it? Is there's a similar effect here as well.

[00:51:47] Daniel J. Levitin: Tourettes is by definition a motor disorder characterized by ticks, unwanted movements. There are some versions of Tourettes that include swearing uncontrollably, and at least with the ticks, musicians who have Tourettes such as Billie Eilish, the ticks almost disappear when they're performing. Again, because the music system in the way that singers can bypass the speech system, the music system takes over the motor system in its service, in the service of playing music.

And so the ticks disappear and it's an island of respite for them. They may not disappear completely, but they're certainly

[00:52:27] Jordan Harbinger: reduced. That's incredible. So it must feel so good for somebody who is constantly suffering from these ticks to play music and sing as much as possible. Yeah, it does. Man. That Tourette stuff is fascinating.

Uh, what many of you may not know is that I also have Tourettes, but it doesn't happen what I'm podcasting. How weird is that? F*cking sh*t. F*cking f*ck balls. We'll be right back. This episode is sponsored in part by Northwest Registered Agent. Starting a business shouldn't feel like taking the bar exam.

With Northwest Registered Agent, you can build your business in just 10 clicks and 10 minutes seriously. And you get more than just a company name on paper. You get your whole business identity set up the right way, right out the Gate. Northwest has been helping people launch and grow businesses for nearly 30 years.

If you wanna build your business and protect your privacy at the same time, this is the move in just 10 clicks and 10 minutes, they'll form your business, create a custom website, set up your local presence wherever you need it, whether that's your home state or across the country. Form your business for just $39 plus state fees, and you're backed by real business experts, not a chatbot.

Northwest is a one-stop business solution formation, paperwork, custom domains, trademark registration, all in one clean, easy to use account. Northwest also protects your identity. They'll use their address on your formation documents instead of yours. So your private life stays private. They even offer premium mail forwarding, giving you a real physical business address totally separate from your personal info.

[00:53:48] Jen Harbinger: Don't wait. Protect your privacy, build your brand, and set up your business in just 10 clicks in 10 minutes. Visit Northwest registered agent.com/jordan and start building something amazing. Get more with Northwest Registered agent@northwestregisteredagent.com slash Jordan.

[00:54:04] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Notion.

Ever feel like you're spending more time managing email than actually getting work done? We've been using Notion for years to keep our production calendar organized, and now Notion Mail is saving us a ton of time and helping me focus on what actually matters. Like a lot of you, I kind of live in my inbox sometimes responding to questions, scheduling interviews, chasing down opportunities.

But email management hasn't really changed in decades. It's tedious, cluttered, constantly pulling you off. Task Notion, mail fixes that. You tell it what's important, it automatically sorts and labels your emails as they come in. I love the custom views feature. You can split your inbox by topic, urgency, sender, whatever keeps you locked in and distraction free.

And for the repetitive stuff like intros, thank yous, scheduling links, notion Mail has one click Snippets that make flying through emails ridiculously fast. And since it's fully integrated with Notion, everything, your notes, your docs, your calendar finally works together just the way it should.

[00:54:55] Jen Harbinger: Get Notion mail for free right now at notion.com/jordan.

And try the inbox set thinks like you. That's all lowercase letters. notion.com/jordan to get notion mail for free right now. When you use our link, you're supporting our show notion.com/jordan.

[00:55:11] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is sponsored in part by Airbnb. I gotta give a shout out to Brian McDonald, who listened to the show and absolutely hooked me up in Vietnam.

Recently, Brian runs a taste of Hanoi, and I had this layer over in Hanoi, and he's like, I got you. Set me up with one of his guides for a motorbike food tour in Hanoi, which is awesome. Now, if you've never been in the back of a motorbike in Vietnam, it's something, man, you're weaving through scooters and traffic like a video game where you can actually die, and then all of a sudden we're inside someone's house.

Literally inside we rode the motorbike. I, I'll tell you here, here with the guide, pulls into what looks like an alley, okay? But it turns into a hallway, and then he turns around grins and goes, okay, put your hands on my shoulders. Duck your head down. Pull your knees all the way in. The next thing I know.

We're riding through someone's living room. Not even kidding, like actually someone's living room to get to this little courtyard kitchen where this auntie is making fa. That'll just ruin your life. No fa will ever taste as good. And Vietnamese egg coffee upstairs on the balcony. I don't even know how to describe it.

It's like tiramisu and espresso. Had a beautiful caffeinated baby. Short trip, chaotic, absolutely incredible. And I can't wait to go back and bring Jen next time because I know she's gonna love it. And next time we'll put our place on Airbnb to help fund the adventure you can too. Airbnb makes it super practical.

It doesn't take a lot of effort. You set it up before you leave, and then boom, your house is earning money while you're on vacation and making memories. Your home might be worth more than you think. Find out how much at airbnb.com/host. If you like this episode of the show, I invite you to do what other smart and considerate listeners do, which is take a moment and support the amazing sponsors who make the show possible.

All of the deals, discount codes, and ways to support the show, our searchable and clickable over at Jordan harbinger.com/deals. If you can't remember the name of the sponsor, you can't find the code, go ahead and email me. I'm happy to surface codes for you. It is that important that you support those who support the show.

Now for the rest of my conversation with Daniel Leviton, what about ms. Multiple Sclerosis in Music? I've got friends who've had this. It's something that scared a lot of us because we were all getting older and some of my friends just suddenly had symptoms of this. Can you describe what this is and what it does to your body?

[00:57:10] Daniel J. Levitin: Multiple sclerosis is a neurodegenerative disease that attacks the myelin, which is the insulating sheath. Around the neurons, neurons are sending electrical signals and like the wiring in your house or in that microphone that's in front of you, they need to be insulated so they don't short circuit or arc.

The wires in your home have rubber around them or some rubberized plastic or insulating material wires, as it were in your brain, have myelin, which is a fatty white substance, and that's why we call it white matter. It's after the white insulating sheath. When that sheath becomes degraded due to the disease, it causes a lot of things, memory, trouble.

Your neurons are not speaking to each other properly. Memory, trouble, movement, disorders, fatigue and music plays a role there in all of them, but for different reasons, music motivates you through the dopaminergic system. So to help you get over the fatigue, it can help with memory problems to the extent that music can serve as a cue for some memory and in the way of Parkinson's, it can help people with MS to walk and move more continuously and speak better.

[00:58:22] Jordan Harbinger: It's very scary. I've read some research that this comes from the same virus that causes mononucleosis, which I had that in college. Epstein Barr virus. Yes. So I think I got it from like, I don't know, going abroad and kissing girls in bars or something in Panama. Who knows? They called it the kissing disease.

Yeah. 'cause it was transmitted by saliva. Yeah. That is just really scary. Why do some people get this and other people don't? Do you know, I'm not an epidemiologist, right?

[00:58:51] Daniel J. Levitin: Caveat, and I'm not a physician. I'm just a simple country neuroscientist. But what I do know about Epstein Barr is that if you were to test the entire population, something like 90% of us would have Epstein-Barr antibodies.

I see. Even still now you would have them. The question is whether you become symptomatic, so mononucleosis, Epstein Barr, far as I know, same virus monocle is a manifestation of the virus. Some people have a recurrence of it later in life. That mono can come back 10 or 15, 20 years later. Sometimes it's diagnosed as chronic fatigue syndrome.

Sometimes it can become narcolepsy if there are other factors, but most of us are able to live with it and keep it in check. Some of us can't. We don't really understand the body's ability to fight these invaders very well. I see. Which is why long covid is still a thing. We haven't figured that out. Some people get it, some don't.

Seems not to be particularly related to which strain of covid you got or how severe your case was. So Captain Kirk used to say space, the final frontier. Yeah. I think the brain is the final frontier. Yeah. It's a vast, undiscovered,

[01:00:12] Jordan Harbinger: uncharted territory. It can be a little bit scary for those of us that are up in our forties and stuff happening to our friends, and it just, it starts to get real.

You mentioned with the stuttering and the Tourettes that there's almost like an alternative pathway in the brain for some of these things. I think a decade ago or so we talked about paradoxical kinesia. So how an old grandma can fly into action and maybe move super fast in an emergency, or how someone can lift a car off of their baby if it's trapped under the car.

Is this the same kind of thing? How does this work?

[01:00:47] Daniel J. Levitin: No, I think this is different. I think. That is attributed to a sudden burst of adrenaline and some other factors. We're not talking about adrenaline here in a fight or flight emergency response. I think a better analogy is what happened with Gabrielle Gifford's, the congresswoman from Arizona, shot in the head in 2011 and she was shot, the bullet entered a part of the brain that is involved in speech, broke his area and she could not speak after the injury, but she learned to speak and you can hear her give speeches now in 2025, and she sounds quite fluent.

She used what was a technique called melodic intonation therapy. It turned out she, this has been well known for a hundred years. Some people who can't speak can still sing, and so she was taught to sing things, simple things, but necessary things like, show me to the bathroom, or I need a glass of water.

And by repeating these songs. In the Intact Music system, the musical circuitry is separate from the speech circuitry. You're still making very similar movements with the jaw and the lips and the tongue and the larynx, but it's music, so it's a different system. And this gets to a fascinating evolutionary issue, which is the brain wasn't designed.

It's a Swiss army knife that evolved to solve a bunch of different adaptive problems. And so there's a speech system that evolved separately from the music system. And of course, if you were to design it now, you'd design it entirely differently. You'd make them a single system. Why wouldn't they be? They use a lot of the same capacities, a lot of the same operations, but they evolve separately for that matter.

The neurochemical system that evolved there are a hundred different neurochemicals. Crazy. You don't need a hundred neurochemicals. And by the way, the neurochemicals don't do anything. I see themselves, we say a dopamine motivates you and oxytocin makes you feel bonded. That's a very sloppy shorthand.

Okay. Your listeners are gonna hear this first, because most neuroscientists won't tell you this. What they do is there are circuits in the brain that relax you, circuits that make you feel bonded to other people, circuits that motivate you. Those circuits evolve separately from one another, and it just so happens that they evolve so that a very particular neurochemical binds with receptors and activates the opening of those circuits.

So we think of it as like a key and a lock. Yes. A key. Yeah, that makes sense. But if you were to design it from scratch, you might only need four neurochemicals. Huh? An excitatory one that is short acting. Like adrenaline, it doesn't stay around for a long time. An inhibitory one that's short acting. And then a long-acting excitatory and inhibitory.

Long-acting things like immune function. Yeah, four neurochemicals would do the trick, but we have a hundred.

[01:03:46] Jordan Harbinger: Wow. All because they evolve separately at different times, different ways. So it's just redundant. But hey, it works out for somebody who has a little bit of brain damage, right? Because they can use that other system to communicate in ways that the other system is now damaged.

So is that why if someone has a stroke, similar to a gunshot wound to the head, they can maybe sing what they need or sing communication and something along those lines, as opposed to speaking if they can't speak anymore.

[01:04:13] Daniel J. Levitin: There are a lot of demonstrations of this and some recent work being done at uc, Berkeley by Robert Knight, my colleague there where, you know, a patient came in just recently.

Who had a stroke and spoke in what we would call a word salad. He could not say the words to happy birthday when he tried. He said words that didn't belong in it and he couldn't get full words out. And he was like, just, huh, closet. Okay. Poor guy. But he could sing Happy Birthday, perfectly fine. And so Bob Knight taught him, you know, the li guy, his grandfather, he likes going to the meat counter, the butcher to order pork loin.

So Bob taught him a little song, go to the meat counter, sing the song when you wanna order pork loin. 'cause you can't speak to the butcher. So the guy goes

[01:05:00] Jordan Harbinger: and he sings to the butcher. I'm trying to imagine what that is. I'd like pork line. Does he have to finish the whole thing or is it just like one line?

[01:05:07] Daniel J. Levitin: Yeah. Yeah,

[01:05:08] Jordan Harbinger: because the butcher could be like, I got it. I see you every Tuesday. I know already, man,

[01:05:13] Daniel J. Levitin: that would be today. Could you give me some pork line? Yeah. Tomorrow I'd like some hot dogs.

[01:05:21] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, we're laughing at somebody who had a stroke. We are terrible people now. I'm not laughing at that person. Well, he laughs about it too. Of course. I would hope so. Look, he can communicate after a stroke. It's amazing. There's nothing more awesome than that. What about music instead of, or in addition to drugs?

I mentioned the painkilling thing earlier, but what about conditions like dementia? There's drugs for this. Do they work well? I don't really know. I don't think there are cure roles or even highly effective at this point. Are people working with music on this or is it just in the research phase?

[01:05:54] Daniel J. Levitin: We cannot cure dementia.

We can possibly slow it down with drugs, and there are some experimental drugs for this and some standard drugs. Rivastigmine is one of the promising approaches. The last time I looked, which is about four years ago, there are other things coming down the pike. These new GLP ones that gave us Ozempic the next three to five years.

I think we'll see some really dramatic movement there. But the role of music is, that's most apparent is that oftentimes people with dementia are experiencing a loss of memory such that they don't recognize loved ones, they don't know where they are or how they got there, and they may not even recognize themselves in a mirror.