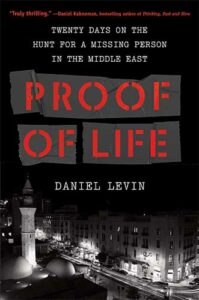

Daniel Levin is an attorney, political commentator, and author of Nothing but a Circus: Misadventures Among the Powerful and Proof of Life: Twenty Days on the Hunt for a Missing Person in the Middle East.

What We Discuss with Daniel Levin:

- How the Syrian regime kidnaps westerners and blames the opposition, keeping them in captivity — often for years — as bargaining chips.

- How Daniel became the go-to person for hunting down a missing person in Syria when no government, embassy, or intelligence agency would help.

- What proof of life means in a kidnapping scenario, and how someone in search of a missing person goes about finding this.

- How people use leverage to get what they want from one another in a place where no one does a favor without wanting something in return.

- The nuances of negotiating with criminals.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

In this episode, Daniel joins us to discuss what it was like to chase leads throughout the Middle East, meeting with powerful sheikhs, drug lords, and sex traffickers in his pursuit. Along the way, we learn why westerners disappear regularly in war-torn parts of the Middle East to serve as bargaining chips, how proof of life is established to determine if a hostage is still being held captive, how trusted Western institutions — including banks and the media — are complicit in regularly putting westerners in harm’s way, the nuances of negotiating with criminals, and much more. Listen and learn!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- Squarespace: Go to squarespace.com/jordan to save 10% off your first purchase of a website or domain

- Adore Me: Shop now at adoreme.com

- Bombas: Go to bombas.com/jordan to get 20% off your first order

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- Progressive: Get a free online quote at progressive.com

Miss our episode with FBI hostage negotiator Chris Voss? Catch up with episode 165: Chris Voss | Negotiate as If Your Life Depended on It here!

The Adam Carolla Show is the number one daily downloaded podcast in the World! Get it on as Adam shares his thoughts on current events, relationships, airport security, specialty pizzas, politics, and anything else he can complain about — five days a week on PodcastOne here!

Thanks, Daniel Levin!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Proof of Life: Twenty Days on the Hunt for a Missing Person in the Middle East by Daniel Levin | Amazon

- Nothing But a Circus: Misadventures Among the Powerful by Daniel Levin | Amazon

- Daniel Levin | Website

- Foundation Board | Liechtenstein Foundation for State Governance

- Civil War in Syria | Global Conflict Tracker

- ISIS Beheading US Journalist James Foley, Posts Video | CNN

- ISIS Says It Killed Steven Sotloff After US Strikes in Northern Iraq | The New York Times

- Obama Calls Islamic State’s Killing of Peter Kassig ‘Pure Evil’ | The New York Times

- American Hostage Kayla Mueller Possibly Given to ISIS Fighter as ‘Bride,’ Officials Say | KTLA

- ISIS Claims American Hostage Killed by Jordanian Airstrike in Syria | CBS News

- Inside Secret Syria Talks Aimed at Freeing American Hostages | Los Angeles Times

- Red Brigades | Wikipedia

- The Business of Kidnapping: Inside the Secret World of Hostage Negotiation | The Guardian

- Proof of Life: Seven Lessons on How Families Can Handle Kidnapping | ABC News

- Evaporated in Syria, the World’s Most Dangerous Place for Journalists | Vanity Fair

- Captagon: The Drug Turning Lebanon and Syria Into Narco States | Channel 4 News

- Marie Colvin: Syrian Government Found Liable for US Reporter’s Death | BBC News

- Tom Wright | Billion Dollar Whale | Jordan Harbinger

- Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World by Tom Wright and Bradley Hope | Amazon

- What Are the Panama Papers? A Guide to History’s Biggest Data Leak | The Guardian

- Where is Gaddafi’s Money? | Süddeutsche Zeitung

- Anderson Cooper | The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty | Jordan Harbinger

- ‘Media Is Hypocritical When It Comes to War Zone Freelancers’ | Journalism.co.uk

- Pervitin: How Drugs Transformed Warfare in 1939-45 | The Security Distillery

- There Is a Secret Apartment at the Top of the Eiffel Tower | Architectural Digest

- Dig Your Well Before You’re Thirsty: The Only Networking Book You’ll Ever Need by Harvey Mackay | Amazon

- 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report: Syria | United States Department of State

- Sammy “The Bull” Gravano | Mafia Underboss Part One | Jordan Harbinger

- Sammy “The Bull” Gravano | Mafia Underboss Part Two | Jordan Harbinger

617: Daniel Levin | How to Find a Missing Person in the Middle East

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:02] Daniel Levin: First of all, I don't get involved in ransom negotiations. And the reason I don't do that is a personal conviction, where I'm deeply convinced that the moment you open up discussions for ransom, basically, even if you get someone out, you just insured 10 new hostages. I understand that it's heartbreaking and you just have to step away in situation. There were cases including an American in Syria, where I was asked to get involved by a politician. And when I called my friend to see if there was anything we could do, he said, "Don't touch this one. They're negotiating a ransom behind your back. That would be paid by the catalyst. And this person ended up getting out because a ransom was paid. But what I know is he gets out 10 more people get taken.

[00:00:47] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We have in-depth conversations with people at the top of their game, astronauts and entrepreneurs, spies and psychologists, even the occasional journalist-turned poker champion, Russian chess grandmaster, or former Jihadi. And each episode turns our guests' wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better critical thinker.

[00:01:14] If you're new to the show, or you're looking for a handy way to tell your friends about the show, we have episode starter packs. These are collections of top-rated episodes, organized by topic. They'll help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show. Just go to jordanharbinger.com/start to get started there on the website. They're also in Spotify. You can also use these start pages to help somebody else get started with the show. And I love it when you do that because that's how we grow and keep the lights on around here.

[00:01:38] Now, today's episode, I realized after I did it here, there may be some confusion. If you haven't read any of this story, people might be a little bit lost right in the beginning, but I'm pulling out a lot of the story itself and a lot of useful lessons from the story. So let's forget it — look, the book is great. You should read it. But at the end of the day, it's about the lessons in the book. So even if you get a little lost in the beginning, bear with us, we'll have some takeaways that you can use as you'd expect from this show. The story is about a missing person in Syria, but it ends up really being about human trafficking and the horrors of the Syrian conflict and human fallout and collateral damage thereof.

[00:02:10] It's really such an interesting story, but Daniel Levin is an extremely interesting fellow. You rarely meet people. Now, by way of background, Daniel Levin runs an NGO that has a lot to do with developing young leaders in the middle east. And so what this means is as a result, he is essentially the go-to guy when somebody gets kidnapped or goes missing in a place like Syria where no one has any reach. It's just a black box for even places like the Red Cross Red Crescent, just have no idea where people are because Daniel — saying a master networker almost just is too cliche. He knows everyone from human traffickers to terrorists’ financiers and leaders of tribes and NGOs, and people respect him on all sides of this crazy sort of battle that is going on in the Middle East, especially in Syria. And he's just an amazing character, the stories quite fascinating. And I know you're going to get a lot out of the show.

[00:03:08] If you're wondering how I managed to book all these amazing folks for the show, it is because of my network. In fact, this episode was suggested by a show fan. I'm teaching you how to build your network for free over at jordanharbinger.com/course. The course is about improving your networking and connection skills and inspiring others to develop a personal and professional relationship with you. It'll make you a better networker, a better connector, and a better thinker. That's jordanharbinger.com/course. And by the way, most of the guests on the show subscribe and contribute to the course. And as you'll hear, Daniel Levin is an extremely good networker. That's the basis for the whole episode here. So come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong.

[00:03:44] Now, here's Daniel Levin.

[00:03:48] What do you do day to day? You know, what is your sort of day-to-day job, if you will? Because it sounds like from the book you have quite a diverse repertoire of skills, I guess, you could say.

[00:03:58] Daniel Levin: I don't know, it's a diverse repertoire of sh*t. I'm not sure it's skills, but I run this foundation. So right now, we're doing two projects in Libya and Yemen. And there've been really hard because one of our Libyan staff has got killed at a roadblock a few days ago.

[00:04:15] Jordan Harbinger: Oh god.

[00:04:15] Daniel Levin: And one of our Yemen staff is a woman, got kidnapped in Yemen. After this podcast, I'm going to take a nap, actually.

[00:04:22] Jordan Harbinger: I don't blame you. Yeah. That sounds quite intense. Why do people come to you wanting help with missing people in Syria? You know, why you? I don't know who I would call if a friend of mine, well, besides you, if a friend of mine went missing in Syria, I mean, the list is short.

[00:04:37] Daniel Levin: So Syria specifically, the context was that our foundation got active after everything fell apart in 2011. We were asked initially in the war, when the war broke out at 11, 12, it wasn't really clear who was going to emerge from that war. This was before Russian intervention in 2014. And the Iranian intervention was only incidental through Hezbollah and Hezbollah was actually getting their ass kicked in Lebanon too initially. So it was really unclear. The US was all over the place supporting Free Syrian Army.

[00:05:04] So we got contacted by the various groups in Syria, actually by certain groups. First, the government and one opposition, our condition was everyone has to be on board to help mediate the conflict. And our condition for doing that was the way, I mean, when I say we, our foundation, was that the only way we get involved in these conflicts is by them giving us sort of next generation people. In other words, young people in their 20s or 30s that we can then train for post-conflict work. Otherwise, we didn't feel like just mediating for the sake of, then everybody's saying, "So sorry but we don't have anyone to take over."

[00:05:36] So they were fine with that. And we got to take about 25 people in Syria and the project — we call it Project Bistar at the time, 2012, 2013, and train them outside the country on any kind of leadership, anything from political leadership, basics on economics, trying to develop a new exchange in different parts of the country. And that was the work that we were doing. And because of required all the stakeholders to be supportive of that, we ended up interacting with the top of the regime, top opposition. This is before major Islamist intervention, the country, ISIS and other groups in 2014. So the most radical groups at the time were the local Al-Qaeda, which is Nusra in that context. So it was really before things completely fell apart.

[00:06:19] And when things started to fall apart, we stopped our project. But because we had this network of relationships to all the sides, we got contacted by both families and governments, asking where the first of all, do you know what happened to this person? And secondly, if in fact, he was kidnapped and held hostage, can we get proof of license? And then if you're lucky enough to negotiate a release. So that was kind of the cascade, but it all started because of the work our foundation was doing, which is really often what happens. It's not like our foundation is into the business of hostage negotiations. It's really incidental to our work, but it happened.

[00:06:48] And even today, as we speak in 2021, there are, I am just aware of 13 Westerners with that I mean, Americans, Canadians and Brits who are being held hostage in Syria, whose names have not made the public news. So I'm not talking about those we've know publicly about, so this is an underserved part of this dark underbelly of these wars that people don't really talk about.

[00:07:10] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned in the book that most missing person cases in Syria don't have happy endings. So it's actually kind of got to be a bit heartbreaking to work on a dozen or two dozen missing persons cases, just knowing that the odds are really stacked against finding this person happy and healthy or possibly at all.

[00:07:27] Daniel Levin: It is. And in fact, you know, when this story took place, this is late 2014, I was done. I didn't want to do this anymore. And I got roped into this story because I just had a really bad experience where I was asked to help with the hostage negotiation. And about two days before I was supposed to really enter the negotiation physically and meet them in Syria, they executed the hostage. And I had worked on that for nine months, got to know the family and everything. So I was really done with this. I didn't want to do this anymore. And 2014, it was particularly hard year. This was the year, the fall of that was where to James Foley got decapitated, put on YouTube, and Steven Sotloff, and then, you know, Peter Kassig and several journalists in particular, but also aid workers. And so I really didn't want to do this anymore. I'd had a really bad experience in 2013, also.

[00:08:13] So for the very few moments where you can give families just good news, that their hostages are alive and the very rare moments that you can negotiate a release, you have so much heartbreak. I was done and I was roped into this sort of under false pretenses. I was asked into a meeting and the person just broke down in front of me. And I felt like I couldn't just walk away. So it is really hard. And even today, when I'm asked for help, it's very hard to deal with more than one of these situations at a time just emotionally. And usually I try also not to get too involved with the family. I try to communicate with the family themselves as little as possible, and usually in writing, because once you are vested and you really feel part of it, you just don't have the distance anymore to make good decisions.

[00:08:51] Jordan Harbinger: What kind of decisions would require you to be more cold or calculated? Because it sounds like you don't want to, you want to sort of minimize, I'm trying to say this without making you sound bad because, of course, it doesn't. It makes you sound effective. But you sort of want to minimize the amount of empathy you have, right? In a way, I mean, what you're doing is, is admirable and it's sort of like the most sympathetic act that you can have, but you're also trying to make sure you don't cloud your emotions. But what sort of decisions require that during a negotiation like this?

[00:09:19] Daniel Levin: Hostage negotiation of wars, and I know you have you spoken to a lot of hostage negotiators, I'm not talking about the tactics of interacting with the hostage takers. I'm just talking, first of all, about the basic logical constellation and the geopolitics of it. So even in Syria, whether if it's the regime that holds someone, that's a completely different approach than let's say the Islamist groups that hold someone. Sometimes people are taken hostage just for the shock value of executing them.

[00:09:41] One thing that's common to most hostile situations in wars, on Syria in particular, is that you do not want to drive up the perceived value of the hostage in the names of the hostage takers. And that means the first thing you have to do is tell the parents to stop doing something that they want to do. And that every schmuck under the sun and from government to other kinds of advisors telling them to do, which is to seek public support, right? To get public statements, to do Facebook campaigns, and t-shirt campaigns, and have the secretary of state say, "Hell, we're not going to leave a stone unturned until this awful act as being brought to justice and no one's going to rest until so-and-so comes home." All those kinds of campaigns really hurt you because all it does in the eyes of the hostage takers is convinced them that they have a really high value asset, usually a much higher value than they actually have.

[00:10:31] And so what just happens with that is your price went up before you even started negotiation. So the first thing you have to do is really be cold to the parents and ask them to stop doing them. And from experience, I've learned that, usually just ask them to do it, they don't want to hear that, right? Because they have all these people, who supposed to know what they're doing from, you know, the state department, special envoy for hostage negotiations, to anyone else, claiming that these public campaigns are really good. But they don't realize that everyone doing those campaigns has a vested interest. Right? It's kind of like a divorce lawyer has a vested interest in having an acrimonious divorce because that's the only way they make money.

[00:11:05] It's the same thing here. So all the PR campaigns, all the communication advisors, the congressman from the district, he's thinking about his next reelection. So the fact that he or she, right? So they're going to pass the resolution on the floor and they're going to condemn the evil hostage takers and so on. And all that does is piss them off and drive up the value. So you have to convince the family to do that. And usually just explaining is not going to do the trick because they really want to hear that those expressions of empathy, that they perceive that we are in their interest. So you always get to a point where you say, "Look, you can do this with me or not do this with me. If you're going to not do this with me, I really, really wish you all the best just to understand what you're going to do with the campaign that you're doing right now is going to get your child or your spouse killed." And that's a hard thing to say to a parent. It's extremely harsh. I wouldn't want anyone to say that to me.

[00:11:50] But this is one of the first things you're doing. So you haven't get established months, sometimes years of trust. With some point they realize that you know what you're doing. So all they have is, "Who's this guy, he may have come recommended, but who's this guy telling us that we have to stop talking to the media," right? And it's a really perverse thing. People are mourning, but they really want to have that connection to the outside world. They delude themselves and thinking that these t-shirt campaigns are going to be reported back to their son or their husband, who's in a Syrian prison somewhere in a basement somewhere. So there's all these strange things.

[00:12:21] If you really managed to do this, like an algorithm, basically everything would go dark. And the first thing you'd convinced the hostage takers of is that the hostage has very little value. You can say no value because then they just execute and discard it. So it has to be little value. Then you can approach them and say, "Listen, man, you have a few chips in your hand. They're expiring chips. Let's see what we can do to cash them. What can you get for those chips? Just understand, at some point, they start to expire." But you can't do that either before, you know what it is they would need, because if they then say, "Well, we want A, B, C," and you're not able to deliver that, that's a death sentence too. So there's a lot of nuance, also timing nuance in this process, but the first thing is to get the families to stop talking and stop engaging people to talk and asking all the politicians who claim to be their friends to also shut up.

[00:13:07] Jordan Harbinger: Wow, this can't be easy. Like you said, right? Because, of course, they're writing their senator and their senators like, "Great. I'm going to go on CNN right now and tell everyone to get behind you, which will apply pressure to maybe even the president and certainly the Armed Forces." And you're like, "Great, we're on the right track." And then you got these jihadis or Syrian secular army, authoritarian crazies, watching it and going, "Oh, we thought we had some journalist or a backpacker, but now we've got some guy whose parents are friends with the senator of the state. So we were going to ask for $500,000, but now we should get like five million dollars."

[00:13:43] Daniel Levin: Right.

[00:13:44] Jordan Harbinger: Or, "We should drag this out as long as possible, because they're going to give us media attention if we keep this guy around." So he's more valuable in the basement for the next three years, then he is just a cash grab, which is awful.

[00:13:56] Daniel Levin: That's exactly right. That's exactly right. And then there's other stuff you want to stop. You also want to stop a secretary of state and traveling to Syria and inquiring about it. Because all they're going to hear is, "Oh, of course, we don't know what happened to this hostage. We're totally on your side," while the hostage is dying in their basement, obviously. So all they do is just enforced the hostage takers conviction, the time is on their side. And that's really dangerous because if they think that the value of the hostage will just go up when in fact the likelihood that this hostage will die, because they're extremely difficult circumstances, even without, COVID obviously, to survive many years in captivity, from depression to just physical health, to accidents that can happen to a bombing campaign that you don't know.

[00:14:36] There've been cases of hostages who were killed by friendly fire from allied forces because it didn't know that some building held a hostage in the basement, right? They use human as sheild. So time is never your friend, but the problem is the more you publicly doing, the more your government publicly does, the more the hostage takers in fact are convinced that the value just goes up with time. If they have to hold the person for 10 years. So be it and very few hostages survive 10 years in captivity.

[00:15:01] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I remember there was a story a while back about, I think it was a female, maybe she was military, but she ended up becoming, and I'm putting this in quotes because it's a disgusting situation. I guess, one of these like sort of clerics married her and used her as a wife in a very sort of disgusting way. And then eventually they found out that she most likely died in a US airstrike, which is awful, but also seems to be leagues better than the situation she had previously been in.

[00:15:27] Daniel Levin: There's a case of an American Kayla Muller who was actually kidnapped and was one of al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIS, of his brides essentially. It's debatable whether she died in an American airstrike or whether he actually had her executed in early 2015. So these are really heartbreaking stories, but you don't really know what to wish for, obviously in those moments. They're all just heartbreaking.

[00:15:50] Jordan Harbinger: It really is just sort of the height of human cruelty, right? These people are stuck in just terrible circumstances for 10 years. Their kids are growing up, their families sort of grieved and moved on, but with no real closure at all. It's just such a horrific fate, right? You you're losing years of your life, your health. Your kids think that you're dead. You miss — you know, I have a two year old now and a baby on the way, and I just can't even imagine what if I'm gone for the next decade. They don't know who you are. It's almost better to just be murdered depending on how long you're going to be there, given the horrific conditions, the lack of health care, and the not knowing.

[00:16:29] Daniel Levin: Yeah, it's a miracle to me. Every time I interact with someone who manages to get out and I realized just like how strong that desire to persevere and survive must have to be because people really endure the most horrific things imaginable. So it's inspiring actually. It's something that keeps me going is the few cases of success that you say, "Okay, this just kind of make sense," because there's so much heartbreak in that. And I've seen even hostages come out of captivity and their families and their lives to break apart because they really never overcome PTSD, this massive trauma that they've suffered in that time.

[00:17:02] Jordan Harbinger: I can imagine. It's quite understand. So what is proof of life actually? And I know it's the title of the book, of course, but this might be a dumb question for those of us who do know, but for many of us who are not in the kidnap for hire business or an adjacent business, we might need a little refresher on what that means.

[00:17:18] Daniel Levin: So it's just some background when you have a hostage negotiation, especially in the war zone, what happens is that the first thing actually that happens in the hardest thing to do is to actually figure out who the hostage takers are, because the first thing that happens when someone goes missing and that case is made public, and it's usually unfortunately made public before I'm asked to help. Otherwise, I would say don't make it public.

[00:17:38] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:17:39] Daniel Levin: It's that this industry of mercenaries, of advisors, communication, advisors, middlemen, gatekeeper, they all emerged from the woods and they started offering their services. And what happens within days, certainly within weeks is that you don't really know who's giving you real information, where they came from, and the rumors are off the charts. Every single hostage situation I've been involved, by the time, I talked to the parents, they tell me of several cases of someone who knows someone who knows someone who saw their son. Right? And it's always the same story. He looked really thin. He had a beard, his hair was kind of thin. He looked really unkempt. It's always the same version of something that's made to sound like people know what they're doing. And usually, almost always these reports are wrong.

[00:18:23] So the hardest thing in the course of negotiation is to know that you're talking with the people who actually have the person and that you want to know, of course, if the person's still alive. And so for those two elements, you need to essentially authenticate. It's no different than authenticating any communication, right? And the way you do that is with some form of questions, not enough to do the old sort of 1970s, Red Brigades thing with a picture in a newspaper and anything like that because you can fake so much of that today. The Deepfakes are so amazing. So what you really have to do is a key question that only the hostage can answer.

[00:18:57] So you interact with a family, you ask them for some question or some, tell some nicknames, something that no one would be able to know. And whoever the gatekeeper, the mercenary, the intermediaries, who claims that they have some information of them, ask them for that, ask them, what is my son's favorite meal, whatever it is that. And if they don't come back with it, you know, what was the name of his first girlfriend? What's the name of the hamster that he flushed down the toilet when he was three years old? Whatever it is, right? And if they can't come back with that answer, you walk away. It's immediate triage. Don't even engage. Don't listen to the news. Because usually what they say is, "Well, I may not be able to answer that, but let me give you some information that might save your son's life." Most people don't have the sort of Dr. Spock-like algorithm ability to just say, "Stop. Don't talk to me anymore because anything that's coming after now is going to be nonsense." Right?

[00:19:44] So they still want to hear you holding on clinging desperately to desire to hear anything. Proof of life is getting that type of authentication. It's not so much only that the person is alive, but rather that you're actually communicating with the people are holding the person. And that's key. If you can't establish that, it's the first thing you have to do. Before you try and find out where the person is, before we figure out what kind of a rescue plan, what kind of a package to trade in, what all those things, first thing you have to know is who has them and in what condition is the person.

[00:20:13] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. That's interesting. You mentioned the Red Brigades, this is the OG sort of proof of life is have them stand there, holding a copy of today's New York Times or something with the date visible on the cover. But yeah, like you said, now, I mean, you're just a really clever Photoshop away from being able to do that with any sort of photo that they might've had, that could be years old at that point.

[00:20:35] It sort of reminds me of how in online dating, you know, with catfishing, where you're not sure if you're talking to somebody who's living three towns away or as like a scammer from an African country or some Eastern European place, you say like, send me a picture of yourself, holding three fingers up on your right cheek and your thumb up of your other hand. And then they're like, "Ah, I got to go. It's time for work," or something. You know, they make up a bunch of excuses and/or you never hear from them again. Right?

[00:21:00] Daniel Levin: I'm really happy I met my wife before online dating.

[00:21:03] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, me too.

[00:21:03] Daniel Levin: I could have fallen for that.

[00:21:04] Jordan Harbinger: Me too. I met Jen before all that and now friends are like, "Oh, you know, I met with this person and there's a million different issues with it." Not to just sort of trivialize what we're talking about here on the show, but yeah, just making sure somebody is who they say they are turns out to be a whole art in itself in many contexts.

[00:21:21] Daniel Levin: Right.

[00:21:21] Jordan Harbinger: So you get this sort of secret questions. I think one of the ones from the book was the missing guy had a favorite food that wasn't just like spaghetti and meatballs. It was something a little bit more unique. The hamster that he flushed down the toilet when he was three years old. It sounds like something that would be really — what you're looking for is something that's basically impossible to fake and that isn't in documentation somewhere on the Internet, right?

[00:21:42] Daniel Levin: Right. And in this case it was a character from The Jungle Book. And it was something that no one would ever guess or reverse engineer. It's kind of the same thing as you know, you don't use your birthday as your password for your ATM card or something like that. And you'd try something a little bit different and something memorable.

[00:21:56] So it's pretty easy to agree what proof of life signals would be. And if you can't get that, it doesn't mean you stop the search of the negotiation, but you go at it in a completely different way. In other words, it's not like I'm a theorist about it or I'm not going to talk to anyone who can't authenticate them, talking to the right person. Because most hostage negotiations in war zones require you to work like an onion you're peeling and peeling and peeling before you even get there. It's not like I fly in somewhere and just say, "Okay, well, then I have a question to ask the person. Don't waste my time without that." It's that you're even trying to get close to the group that might be able to answer that question. So there are layers of games and counter games and their chips you're cashing and all kinds of three-party deals, essentially, just to get close to the group. But when you get there, that's the part you need to do.

[00:22:38] Jordan Harbinger: What is the difference in dealing with these types of groups? You mentioned it's different if your loved one gets kidnapped by the Syrian government versus an Islamic group. How do you sort of figure out what these groups want?

[00:22:51] Daniel Levin: First of all, the really big difference, which is the Syrian government if they kidnap someone, you have to have a major favor that you can do for them in order to get a release, because what happens is the moment they kidnap a Westerner, they can't admit that they have them. So in other words, the time gap between when they start the negotiation and when it's concluded, it's maybe a day. Because the moment they admit that they have this person, if this person dies, you're triggering all kinds of wraths from sanctions to potential Tomahawk missiles.

[00:23:23] So they never ever admit it. There isn't a case where they ever admit it. When you have handoffs with those Syrian government, no one ever finds out that it took place. There's no public press conference when the person returns because they really don't want their fingerprints on it. And very often the government has it, not because they want it to take the Westerner, but because one of their militias that works with them, like in Syria, for example, the Shabiha, you have these thugs, these steroid-infused thugs that roam the streets, in the coastal area, in Aleppo and in Damascus, they take hostages, deliver them at the state prison. They didn't ask for them, but now they have them. And it's kind of the Pottery Barn rule. They break it, they own it.

[00:24:00] So they don't really admit it. You're in a completely different situation. Whereas they, Islamist is groups. You have to make a big distinction, which is, do they have the hostage because they want to trade for something, money, attention, whatever it is, or they have the hostage because they want to execute it publicly for recruitment and shock value. And you have to make that brutal distinction. I've been in situations where I knew that it was the latter and I had to go back to the parents and say, "Look, I'm going to do what I can, but you have to understand who they are." I have to be honest about that. And it's the hardest conversation you can have, which is because they're basically waiting for the child's execution.

[00:24:32] Jordan Harbinger: Oh god. That's so horrible. I've got journalists, friends that do crazy things like sneak into Syria across the Turkish border. And the Turkish troops are shooting at them. And I'm thinking, you're lucky if you get hit instead of kidnapped in Syria.

[00:24:47] Daniel Levin: Tell them all to stop doing that. 95 percent of the cases I got involved in Syria where people thought, "Oh, we're just going to go in because we were told it's okay." And then they don't even realize that the people would take them in already worked for the groups that are going to kidnap them. They'll drive them straight to the prison.

[00:25:01] Jordan Harbinger: Oh my god.

[00:25:02] Daniel Levin: Yeah. If anyone ever tells you they have a great idea, I know people who thought that they know aspiring journalists, so could get their newspapers published and just desperately trying to write war reports, trying to be this great reporters that they just can't be, and they can't get their pitches even answered. And then they say, "You know what I'm going to do. I'm just going to go into Aleppo and I'm going to take some photo, shoot and report from that. And that's going to win me a Pulitzer." They're starting to think through that kind of stuff. They make it 10 minutes and they connect with someone in Southern Turkey. And that person speaks broken English and says, "Oh, I know where I can get you in and out just like that." You know, within an hour of being in Syria, they're in the hands of ISIS or Nusra or any other of these rebel groups.

[00:25:42] Jordan Harbinger: Oh my god.

[00:25:43] Daniel Levin: That's exactly how that goes.

[00:25:44] Jordan Harbinger: That is a nightmare scenario. This is one of the most horrible fates I feel like you can meet as a — this just doesn't even compare to being drowned or in a house that's burning down. I mean, you've come into contact with some of these people and some of these characters in the book, these are, I would say, the worst living people on the planet right now, or kind of congregating in this area and in this particular industry, dealing with human trafficking and kidnapping and hostage taking, I mean, I can't really think of worse humans. I don't know if you can.

[00:26:14] Daniel Levin: Well, it's funny. I mean, obviously you see, you're in the midst of a thriving war economy, and whenever you're in a thriving war economy, you see the ugliest side of human beings, right? So whether someone's trading in blankets or water, mineral water, or in little girls taken from their villages sold into prostitution or Western hostages or drugs or chemical weapons, it's all the same. Once you're in a war economy, there's no moral distinction. There's this amphetamine Captagon, that I write about in the book, that's being massively traded fueling war.

[00:26:42] So once you're in a war economy, you see the ugliest side of humans, but there are a couple of things I want to add to that when we're handing out kind of human ugliness awards here. And I want to be clear about that because I feel this really strongly. And I live this really strongly. If you're going to look about the ugliest side of humans, then there are some enabling groups that you should be including in this.

[00:27:00] So for example, the astronomical cash profits that these war economies turn out, whether it's human trafficking, weapons trades, you name it, drug trade, right? Those cash profits have to be formalized, legalized, laundered in our financial system. There are top Blue Chip top 20 Western banks that fly planes into capitals in Southeast Asia to pick up containers full of cash and put them into a vault for the sake for 30, 40 percent discount. Use them the cash money to fund the Russian cash economy because of sanctions is purely dollar base and are exactly part of this war. No different for me than the guy who manufactures Captagon, some amphetamine in a lab and trades it for some 13-year-old girl that he then serially rapes for the next half year.

[00:27:47] So to me, I'm very careful with these kinds of moral distinctions. And the other angle, the other category, which I'm going to add on here, I know it's inflammatory, but I'll say it because I feel it, there's have no incentive to hold back, is that if you're talking specifically about journalists, the little dirty secret of a war zone, such as Syria, which is particularly ugly, is that the top newspapers, whether you're talking New York Times, Washington Post, Frankfurter Allgemeine, Lemoore, it doesn't really matter. Okay. The financial times don't really want to send their own staff and correspondence to those wars for understandable reasons.

[00:28:18] So what happen is you basically have these so-called freelancers, they are often college kids, people just out of college, can't quite figure it out. And they're saying, "Hey, you know, I'm going to go there," and they're incentivizing them to take on those stories and take on risks. These kids are completely unprepared for. I know you hear the big stories like Marie Colvin, the journalist with the eyepatch, who was killed in Syria in the war or James Foley who was decapitated. Those are journalists who have experienced, experience of the war, but most of the journalists who get killed in a place like Syria or Yemen or Libya are freelancers who are really trying to make a name for themselves. And they're being exploited, if I can use that word, by the media platforms that would never send their own. I'm not even saying their own children. I'm even talking about their own staff journalists to those areas.

[00:29:06] So there is an angle to that, that's really unsavory. And it's very easy to condemn the drug dealer and the weapons dealer and we should, and it's hideous beyond description, but I think the enabling industries that exist well outside this war zones deserve a little bit of shame in this context too.

[00:29:23] Jordan Harbinger: I agree with you. I'm going to be doing a show about Western enabling or just enabling in general of a lot of these, yeah, money laundering, frankly. I don't know if you're familiar with the book, Billion Dollar Whale.

[00:29:34] Daniel Levin: Sure. Tom Wright and Bradley Hope are good friends.

[00:29:36] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. They're great guys. I'm in contact with them and it's disgusting how we'll go, "Oh man. Look at these Cayman Islands, people are stashing money." Try South Dakota, the HQ, one of the world headquarters of just illegal money laundering operations and shell corporations and things like that. And like, you said, private jets full of cash. There are law firms and it's not just Mossack Fonseca and Panama, you know, with the Panama Papers, there are law firms in the United States where guys who are going to Michigan law, like me, get out and get a job there, and don't even necessarily fully understand what they're doing, but sure enough are working for a partner who's maybe running a bunch of money from, like you said, the Captagon trade and just cleaning it on up and hoovering up that money for fees, and there's a lot of. And it really is.

[00:30:27] You're right. There's a reason the law treats accessories to crimes similar to the actual criminal, right? Like you might not have a 13-year-old Syrian village girl locked up in your basement, but if you are laundering money for human traffickers, you are guilty of that crime. And you're right. It might be easy to sort of look at yourself in the mirror or sleep at night, knowing that you're not really getting your hands dirty or as dirty as the guy who's got, the girls locked up in cages in his basement, but you're really the same, the same type of awful human.

[00:30:54] Daniel Levin: I've livedand experienced this now for decades in my job. So for example, the Gaddafi's money guy in Libya, Bashir Saleh Bashir, who for 30 years was basically taking billions of dollars of cash out of the country, putting it in warehouses all over the world, especially in Southeast Asia, like Indonesia and Jakarta. And then having Western banks flying their planes and take it into their vaults. All right. And then that money just disappears because now it's part of the Swiss — and that's before cryptocurrency, which is a total game changer when it comes to this. And so that same guy, Bashir Saleh Bashir, was now in Abu Dhabi who fled to South Africa first. He was very involved in challenging Sarkozy, which led to the fall of Gaddafi. That's a story for another time. That's the same guy who has been involved in laundering some of the Captagon profits from the Syrian war. And there's an access with Abu Dhabi to that.

[00:31:39] So these things are all connected and I'm not trying to — this is not some kind of a crusade against Western banks and things like, all I'm saying is if we really want to stop these dreadful wars, we have to stop these war economies from thriving because these wars really, Syrian war, the country is destroyed. It's wiped out. It's burnt down, whatever metaphor you want to use. The only reason this war is still going on is because the war economy is just throwing off these astronomical profits.

[00:32:04] You want to stop this war, you want to stop refugees, mass migration, this is broken countries, broken cultures, broken generations, you have to start cutting off the war economy. And you're not going to do that without all the outside willing helpers. And I'm not just talking willing helpers in terms of sleazy bankers or trustees, you know, in Panama or in Dakotas or wherever, Cayman Islands, it doesn't really matter. I'm also talking about having interesting breakout sessions at the World Economic Forum in Davos with some of these individuals at some point. Or if you don't want to do that and you say, "Look, man, it's pure capitalism. That's how it is." Then let's stop the moral grandstanding. Just spare me that part please. And then that's fine, then these wars exist as long as the profits to be made. But the part that's so hard to take is this gap between the ugly reality and these empty hollow moral statements that you're hearing all the time.

[00:32:55] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Daniel Levin. We'll be right back.

[00:33:00] This episode is sponsored in part by Squarespace. Why don't you have a website for your personal or professional projects? Are you worried? It might be too distracting from doing the things you do best and you hate the thought of wasting precious time building and maintaining something that's frankly, not even in your wheelhouse. Don't be a disgrace. Try Squarespace. You don't have to know the first thing about tech or the intricacies of web design, because Squarespace covers all of that. So you can focus on the things that are important to you, like selling. Squarespace has all the tools you need to get your online business off the ground. You can even generate revenue through gated members-only content, manage your members, send email communication, leverage audience's insights. All in one easy to use platform. You can also add online booking and scheduling for classes or sessions to your Squarespace website. These examples don't even scratch the surface of what you can do on Squarespace.

[00:33:45] Jen Harbinger: Give it a try for free at squarespace.com/jordan. Go to squarespace.com/jordan and use code JORDAN10 to save 10 percent off your first purchase of a website or domain.

[00:33:56] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by adorme.com. Don't let Valentine's Day sneak up on you. Check out adorme.com, which offers hundreds of styles and lingerie, sleep and loungewear. An impressive range of 77 different sizes, which I didn't know existed, A cup through I cup, which like a guess it goes that high in the alphabet. I didn't know that extra small to 4X size. Adore Me is the first lingerie brand to offer extended sizing across all categories. They just dropped a Valentine's Day collection with free shipping and returns in case you get the sizing wrong, which I suppose you could, if it goes A through I. Jen's loving her Adore Me lingerie. The quality is amazing. They have incredible pricing with sets that start at just 24.95 and Adore Me is doing their part in sustainability with matching bra and panty sets made from recycled material, recycled underwear. Sleepwear made from organic cotton and digitally printed swimwear to save on water and energy. Subscribe to their flexible VIP membership that gets you 10 bucks off each set, access to exclusive buy one, get free sales and more perks. Do whatever you want in your Adore Me lingerie. They're here to support you. See what I did there.

[00:34:55] Jen Harbinger: Shop now at adoreme.com.

[00:34:57] Jordan Harbinger: Thank you so much for listening to and supporting this show. As you might guess, the advertisers keep things going around here. I would love it if you'd consider supporting those who support us. All the deals and discount codes are available on one page. Jordanharbinger.com/deals is where you can find it.

[00:35:13] And now back to Daniel Levin.

[00:35:17] There's a lot of, yeah, you said it best, grandstanding, right? We can't believe all this is going on. And then it's like, "Well, don't you own 300,000 shares of whatever bank is laundering all this money? Are you not also supplying a bunch of drugs money, or even just supporting this and pretending that you're lobbying for a legitimate cause when you're really just keeping the border open for illegal petroleum exports, whatever it is?

[00:35:42] Because it sounds like what you're saying is the money's just so good that it can't be ignored, but at the same time, people feel the need to sort of whitewash their reputation by saying, "Hey, I'm not doing that." And it's like, look, if you're doing this, what we need to do is just admit it and then talk about it. Otherwise, it's just going to keep going. Because you're right. It almost sort of makes it impossible to stop if we're going to pretend like we're against it as opposed to just admitting that we're not really doing anything. Right?

[00:36:09] Daniel Levin: Right. And I'm not some shareholder activists trying to take down big banks or anything like that. But for me, it's particularly grading when I deal with it on the political level. When I know for example, that I can't get state department officials to stop talking. I know that someone, a hostage is being held by a regime and they keep on making these grand statements condemning this illegal taking and the journalist should be free. And answer is how is that helping that hostage? Answer that question. How is pissing off the people who hold that person's life in their hands helping you? And the answer to that of course, is they don't really care about the hostage. They care about that little three-minute press conference they might give with how many likes they get when they tweak this little statement of theirs.

[00:36:48] And so you have to also tell parents that, you have to understand that you don't know who your friend here is. So it's not just about going after banks and all the enablers, but again, with respect to journalists, I have a particular bone to pick with newspapers and media companies who take advantage of young kids who are completely unprepared for war zones. If you're going to send people there or accept the work there, you at least have to prepare them. Do you understand? Do you know how to use satellite phones? How do they deal with their passport? Do they need more than one passport? Do they leave their passport with someone else? How do they connect with any diplomatic representation, in particular if their own country doesn't have one there? You really train them through that. Do they have a safe house? Do they have connection to the police chief and locally? All those things that you would go through on a protocol level with journalists, they're never prepared for us.

[00:37:32] So when that moment comes, and it always comes in a war zone, so when that moment comes, they have no idea. They just have no idea. And so it is really unsavory at so many levels. It's super easy to look at the drug dealer and the pimp and the weapons dealer, and look at them and think this is just scum. But, you know, I have a slightly more expansive definition of that term.

[00:37:54] Jordan Harbinger: This actually makes. It really is young folks coming out of college and just not being able to get their shot. Anderson Cooper talked about this on the show. He said, no one would talk to him, which is surprising just given his pedigree, but nobody would really talk to him. So he was doing sort of like mailroom stuff. And then he picked up a camera, like a cheap camera and went to Somalia. And this is like the '90s, you know, Somalia was the Iraq, Afghanistan, whatever it is of the '90s. And he just sort of slid on over there with commercial flights and cars, trucks, whatever it was, and started filming. And he luckily didn't get chopped up into little pieces, but now it's even just a more hellish landscape in terms of the conflict itself.

[00:38:36] And like I said, I've got guys my age or younger crawling through holes and fences in the Syrian border with Turkey and then running into the nearest town in the back of a pickup truck to take photographs and do write-ups. And I think a lot of them just don't realize how close they were to ending up in the basement of a Syrian prison.

[00:38:55] Daniel Levin: Right. Yeah. By the time I get involved, it's usually too late, obviously. I get so angry. I've had these conversations with senior people at major newspapers and TV programs and said, "You know, this is just reckless. What you're doing is so wrong, you have to explain this to people." And they said, "Well, we're not forcing them to take those risks." The answer is, you're taking advantage of them. You know, full well, this is someone who wants to make his into his or her name and journalism. That, you know, full well that the way to do that is be a little more reckless than anyone else and take risks no one else would take. And you know, they're going, they're unprepared. It's one thing to go to Switzerland. I'm prepared to go to Sicily unprepared to wherever, it doesn't really matter, to morocco unprepared. It's a whole different thing to have someone go into Syria unprepared.

[00:39:36] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned Captagon. This is a drug that sort of made a cameo or two here on the show with people mentioning it casually. What is Captagon? And well, where does it come from? What is this? It seems to be sort of trending up in the Middle East and especially in the war zones.

[00:39:52] Daniel Levin: Yeah. Captagon is not no drug actually. Captagon is a drug that has existed since the early '60s. It was developed in Germany, not surprisingly, by a company called Chemiewerk Homburg. And it was initially treated as medication, sort of similar to ADD, ADHD medication.

[00:40:08] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:40:08] Daniel Levin: And then was pulled entirely out of medical market within a few years because of the high toxicity level in the heart and the blood that it degenerated, and not just usually addictive too. And what makes it so insidious is it's extremely easy to manufacture. I mean, if you have sort of a high school chemistry set and a scale and some water, you can make Captagon.

[00:40:25] By the way not so dissimilar — I don't know if you're aware of this drug, this amphetamine called Pervitin that the Germans used in the Second World War. It was something that German scientists had developed, which had a big role in the Blitzkrieg. The reasons that the Germans were able to basically travel to Western Europe to Belgium, Holland for four days without sleeping, a lot of the Wehrmacht officers, less access, was because of this amphetamine that they're having. There were rumors that Hitler was taking it, was on it himself, was thereof also really sleep deprived. And so Captagon has very similar properties to that.

[00:40:58] And in Syria, the manufacturing of Captagon really exploded with the war itself. Just basically mass manufacturing it caused an epidemic in Saudi Arabia. I have a Saudi friend, a medical doctor, who told me that he suspects that 50 percent of Saudi males under 25 take Captagon. And it's become a date rape drug. I mean—

[00:41:19] Jordan Harbinger: 50 percent.

[00:41:21] Daniel Levin: He suspects Saudis under 25, just as crazy number there. When they find Captagon, and it comes in all kinds of ways. It's often delivered in blister packs to make it look like medicine. When they find it, the hall is often worth five, six billion US dollars. Those are the kinds of volumes. It's now making way to Southern Europe into the Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese border, and then from there to Northern Europe, a lot of it now in France. It's an extremely insidious drug and the profits are just astronomical because it costs almost nothing to make.

[00:41:52] Jordan Harbinger: Five or six billion dollars street value makes submarine full of cocaine looked like child's play.

[00:41:58] Daniel Levin: Yeah, the margins are off the charts because it not only costs nothing to do it but it also costs nothing to distribute also. A lot of the Captagon dealers, and I talk about this in my book, because the people who held this young men hostage where the biggest Captagon traders in the country.

[00:42:13] By the way, one of the people who started the Captagon business in the war was the uncle of the current president, President Bashar al-Assad, his father was Hafez al-Assad. His late father brother, Rifaat al-Assad, who was just convicted last summer in a French court. And he was the one who really started to profit massively off the drug trade. So that the intersection, the various groups making money of that, some regime, some opposition, Hezbollah has its hands on Captagon.

[00:42:40] And obviously, a lot of these freelancers, but the person I ended up — I had to flag down and find who held this Western Westerner hostage was probably the biggest Captagon dealer in the country. And they often use the same distribution routes for the Captagon as they do, for example, the human trafficking. So the same people would take little girls from villages and send them to the Gulf, to Dubai, to Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, to other places, primarily those two places though, they use the same distribution routes. Very often they fill also stomachs of the girls with drugs, not only Captagon, with the other drugs, and use them as couriers while also basically shipping them as the product itself.

[00:43:19] Jordan Harbinger: That's horrible. I mean, this is just so dark. The Captagon I've heard hasn't made it to the US necessarily, or hasn't trended up in the US just because we have, to put it bluntly, more effective, sort of better drugs that do the same thing. Like, what is it? Methamphetamine, like different kinds of methamphetamine or something like that. Would you agree with that?

[00:43:37] Daniel Levin: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, the margins would be too small because you're breaking into a saturated market right now. Whereas the market in Saudi Arabia and in Southern Europe is not nowhere nearly as saturated, unfortunately, because of the meth epidemic that we have in this country, it is a saturated market. So that's pure supply and demand thing. There's such a massive amount of supply, despite the huge demand that your margins have to be really small, so it's just not attractive. I mean, this drugs really follow very simple. You know in Adam Smith's invisible hand rules, it's really simple.

[00:44:07] Jordan Harbinger: It's interesting that that the United States is bulletproof from Captagon because we're addicted to so many other things that it. Just there's no room for it. That's like a depressing humor in a way, almost like a ridiculous sort of notion that we just like, "Hey, we have no room in our drug market because we have so many other drugs that we can't get free from. That there's no room for a Captagon." Unbelievable.

[00:44:30] Daniel Levin: Exactly.

[00:44:31] Jordan Harbinger: The way, side note, a totally different topic here. You mentioned that in one of the characters in the book enjoyed going to the top of the Eiffel Tower to a hidden apartment there. Is there really an apartment at the top of the Eiffel Tower?

[00:44:41] Daniel Levin: Yeah, there used to be. Gustave Eiffel, the builder of the tower actually lived there for a while. That's where it was.

[00:44:46] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:44:47] Daniel Levin: What had happened in the book was that the person who asked me for help, I met him in Paris for dinner. I didn't know what he wanted from me. And then we walked through Paris at night and we did this kind of loop that he loves to do. Where at some point, you turn over or you turn around a corner and you see the Eiffel Tower lit up and it was something he always felt was beautiful. And that's when he was reminiscing of that top of secret apartment that Gustave Eiffel, the builder of the tower, kept for himself and definitely, one of the best real estate pieces I would think of worldwide. Right?

[00:45:14] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I was going to say that has to be the most valuable, one of the most valuable properties anywhere on the planet, like owning your own island. No, thanks. So that's for plebes. I live at the top of the Eiffel Tower in the middle of Paris. I mean, that's—

[00:45:24] Daniel Levin: Right, we should probably keep this a secret. There's going to be some tech billionaire and feels like that's exactly what he needs to have. So maybe we shouldn't advertise this.

[00:45:31] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. We'll be done with that, I suppose. You mentioned that you don't ask for compensation when you are trying to help missing people with the hostage negotiations or look for missing persons. Why don't you ask for compensation?

[00:45:44] Daniel Levin: I can't. I'll explain this. First of all, you know, the work that we do it's really incidental to have a foundation work. So my work and the foundation were discovered by the budget of the foundation. So, number one, there's no need to ask for compensation, first of all, but the bigger issue is that it's too full. First of all, I don't get involved in ransom negotiations. And the reason I don't do that as a personal conviction, based on my own days, back to the military in Israeli military, where I'm deeply convinced that the moment you open up discussions for ransom, you basically, even if you get someone out, you just insured 10 new hostages. It's just a personal principle. I understand that it's heartbreaking and you just have to step away in situation.

[00:46:24] There were cases, including an American in Syria, where I was asked to get involved by a politician. And when I called my friend to see if there was anything we could do, he said, "Don't touch this one. They're negotiating a ransom behind your back. That would be paid by the catalyst. And this person ended up getting out because the ransom was paid. But what I know is he gets out, 10 more people get taken. And I don't want that on my hands. That's number one, the second thing, when you start getting involved with ransom negotiations, Jordan, if you think this through, think about the dynamics that happen.

[00:46:54] Let's say there is a one-million-dollar ransom request. Okay. Well, that doesn't come directly to me that comes through layers of gatekeepers, couriers, intermediaries, representatives. By the time that number reaches me, that's $10 million, first of all. Second of all, the moment you have a financial interest, you become vulnerable. Meaning that, the moment any money changes hands and I don't just mean $10 million, I mean a cup of coffee, a meal, a flight, a hotel, a driver, whatever favor that has monetary value that gets thrown your way — I don't even accept meal invitations — the moment there's any monetary value, people start rumors that you got perks or benefits out of it that you didn't share. And that's the way they pressure you.

[00:47:37] Even in fact, in the course of my story, someone said they would spread that kind of rumor. Even it wasn't true here just for the sake of getting something out of me. So the moment money gets involved, it moves you away from resolving the case. Now, I'm not saying you can't do something. There is no quid pro quo. It just can't be monetary. So to give an example, there've been hostage negotiations where a relative of a hostage taker had breast cancer. Mother had breast cancer, couldn't get treatment for a number of reasons. The hospitals in the country weren't working or the family was sanctioned, so she couldn't travel abroad for treatment, as an example. And so through a network of favors, if you can arrange for this person to get treatment in Cyprus or in Germany, and this is just one example that I just went through, that's a quid pro quo, you can offer. Those are favors that change hands, but no one's enriching him or herself personally in that process, but it gets much less cluttered if you take money completely off the table.

[00:48:32] And so that's sort of the Reader's Digest version to your question. It gets much more intricate, but every time money changes hands, it's almost impossible to get involved, unless it's a flat-out huge ransom payments, some outside government pays, and I don't want to get involved with those cases.

[00:48:46] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. That makes sense. It just generates demand. You go to Lebanon to meet this Sheikh and he seems extremely intense. What is he like a terror financier? Is that kind of his position?

[00:48:57] Daniel Levin: No, this is someone who's well-known. This is someone who is, has been sanctioned by the US ever since the '80s. So anyone who reads the footnotes in the books carefully will know who it is, but I made him a promise that I would use a pseudonym when he agreed to help. This is the head, a very powerful head of a political movement and a military movement in Lebanon. I had to use this, I mean, the condition for being able to write this book. I got everyone's consent involved except for the evil people and I named them and shamed them. It's not like they get pseudonyms, but the people get pseudonyms are the victims. The two girls I talk about, the person that was kidnapped himself, and a few other people who made their support conditional upon it being used on their pseudonyms. And that was one of them. And it was critical because he was the one who directed me to, he basically put me on the trail of the people who had this hostage.

[00:49:46] Jordan Harbinger: This guy is extremely intense. The reason I sort of try to tease that out is because you can read the footnotes, but also if you don't really know your way around this sort of conflict, it doesn't really mean anything to you, but the guy is extremely, it's like street smarts, but level 100. You don't just put your phone away, but he sends a handler to deal with you and evaluate you beforehand and take the flight with you and sit next to you to sort of feel you out. And the handler who's intense in his own way gives you this tip. And he says, "Don't beat him with the fist of flattery," I think, right? It was what he said.

[00:50:18] Daniel Levin: Yeah.

[00:50:18] Jordan Harbinger: This is actually a really useful concept. Can you tell us about this? I had never heard of that, but I like it.

[00:50:22] Daniel Levin: Yeah. So the way the whole meeting came up is through the person who's I feel like almost as a mentor or a father figure for me. He's someone called Khalid al-Marri who's a Saudi with a Syrian mother who is in most cases, especially in Syria and in the Gulf, the person who helps me in hostage situations. And he know this militia leaders known him for many, many years. He saved this person's life at some point. And so this person always feels indebted to him. So when he called the militia leader and say, "Hey, can you help with this particular hostage?" The guy said, "I'll help, but you have to send the person who was asking about him to me to see him. I have to see whether I'm going to trust him to share the information." And that was the deal.

[00:51:01] So I had to go, I had to basically see him, what we call dark or blind, which is I flew from Istanbul to Beirut. I landed in Beirut middle of the. And I didn't fly by myself, which is this person sent one of his trusted deputies to pick me up in the lounge in Istanbul and vet me both in the lounge throughout the flight and when we arrived. And if at any moment in that vetting process, I had failed for whatever reason to been too inquisitive, too chatty, not trustworthy in his mind, try to impress him too much, whatever it is that would have triggered it, he would have left me behind and it could have been in Istanbul when, we arrived in Beirut, at any moment in this process.

[00:51:38] And then when we arrived in Beirut and I seemed to pass those tests, I had to give up all my phones, passports and phones, and that means I'm going completely blind, which is I'm surrendering entirely to this group. And this is a group that's in South Beirut. It's a very militant group of very ordinary group, let's use it in a nice way, but I knew that because the introduction had to be made through my friend, Khalid, I completely trusted him. He wouldn't send me in harm's way, but it was still an extremely intense few hours.

[00:52:03] And this aid of this leader told me one thing, don't do, don't try to bamboozle the guy. Basically he's saying don't play the player. Don't bullsh*t the bullsh*t or don't sh*t, the sh*ter. That kind of advice he's giving me. And it's similar to the other advice a friend once told me, which is if you're in the room playing poker and you look around, and you can figure out the sucker is. There's a good chance it's you. And it's the same thing here, which is every smart person. And every really smart and wise understands that when they're being flattered, that the person who is flattering them is trying to claim them, gain them, get something out of them.

[00:52:36] And if you're really enlightened in that sense, the thing you'll be the most suspicious of, it's not someone who's unpleasant or confrontational, you just don't have to deal with that person if you don't want to, but at least, you know, that you have. Where you really have to be worried is when you get the flattery. And it's something very strange about people in power. And you don't have to go to comical proportions such as the last president, even generally, people in power, people can be very shrewd, very smart, and political. Economic power, media power, doesn't really. The one thing people seem really susceptible to is flattery. For some reason, that's our blind spot.

[00:53:10] And I don't mean when I say our, I just have to make the assumption with, even if I don't have power, that it's just a human flaw that people can figure out a way to flatter us in a way that we don't notice and we just enjoy the company of that person. Right? It just releases particular endorphins that make us happy. And the advice I got here is, "You may be really stressful. It may be really hard. You may be sweating like a pig when he'd makes you uncomfortable, but be honest with him. If you'd give him a dumb answer or an answer he doesn't like, it's always going to be preferable to giving him the sense of you're trying to play him. And if you flatter him, even the way you address him, don't use those stupid honorific titles. He's not Your Excellency, he's not Your Majesty, he's your whatever. You just call him Sheikh." And that's in fact what I had to address him at, "And just keep it real. And if he asks you a question. It maybe hard. He maybe asks you about being Jewish, and maybe asks you about America, whatever it is, give him an honest answer. I'm not saying you should go out of your way to insult him, but speak your mind and just be respectful."

[00:54:05] And it was really good advice because it was an extremely intense few hours I spent and that it felt like an interrogation. I always felt safe in that way because even when he disagreed with me, at some point, he said, "Look, I'm going to give you high marks for honesty, if not for intelligence." So there was an insult in there, but at least I knew I was safe. He didn't get angry at me because he felt like I was trying to manipulate him. It was really smart advice.

[00:54:28] Jordan Harbinger: That is interesting. Although I, I have to note that if he's saying don't use his honorific title, just call him Sheikh. It's kind of like saying, "Just use this other honorific title that I have." I don't know.

[00:54:38] Daniel Levin: Yeah. I know. And I wrote that in the book too, but it's so diluted. Sheikh is really much more common. I think in the Gulf, in the Gulf monarchies, UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, people use the word Sheikh with much more kind of pump and circumstance. It's much more puffed up. In the Lebanese, Levant kind of context, it's really not used that way. I have friends when they give me sh*t, they just say, "Hey, Sheikh, how's it going today?" Arab friends of mine. So it's really used in Palestine, Jordan, Syria. It's really used much more colloquially that way. So it really didn't have that flavor.

[00:55:12] Jordan Harbinger: Got it. Okay. Because that did sort of strike me as weird. You're right. I've noticed that you did write about that. I probably parked that in my brain. Because I did think that was strange too. It's like, "No, no, no. Let's be informal. Call me Dr. Jordan," right? It's like, what?

[00:55:25] Daniel Levin: Right. No, no, you're absolutely right. You're absolutely right. And it's in fact even occurred to me when he said it, but in the context that he said it didn't feel that way at all.

[00:55:32] Jordan Harbinger: In your conversation with, he gave you some insight into why some of these groups hate the West. And I thought, this is fascinating, right? It's not necessarily religious. He even noted that the United States is more religious than Lebanon and many other Middle Eastern countries who those countries have religious laws, but as sinful culture. And Sheikh thought America, of course, also has a sinful culture, but is more sort of, I don't know if pure is the right word, but like the people actually believe it. Whereas in some of the Middle Eastern countries, a lot of the people are just sort of performative because they have to be by law. It sounds like he mentioned that he doesn't want America to succeed, but for reasons that seem totally backwards. Can you take us through this? I'm not even sure I got this right because it seems so insane to me, his explanation.

[00:56:15] Daniel Levin: Right. So w we ended up in this discussion, he was drawing me into a discussion. I was getting really both nervous and also impatient, because I was really there just to get information on this hostage. And he was drawing me into this whole religious cultural discussion. I mean, he was challenging my thoughts of Judaism and the fact that I hadn't even realized that every time the symbol of the Eagle was involved, that the Jews were getting wiped out. It happened with the Romans, it happened with the Germans, and it's going to happen to America through a simulation with American Eagle.

[00:56:42] So it was really fascinating stuff, but it was also, I was getting kind of like, can we just get on, can you just give me the information I'm here for, but I could never really say that.

[00:56:49] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:56:49] Daniel Levin: He also gets into civil rights in America and misunderstanding. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, and the distinction between the two is really fascinating stuff. And one thing that he mentioned to me is, he said, "You and the West, you really don't understand us. You think we hate America. You think we just resented because it's a Christian country or because it's a Heredic country, that's not true at all. The reason we resent America is because it has something that we don't have. We here have this tribalism where tribes really—" Don't forget. This was happening 2014. This is before the last five years of that we endured in this country. So maybe he'd say something different today. But at the time, what he's saying is, "You're not beset by this tribalism. America's really founded on being a multicultural society."

[00:57:32] And he was very critical of America in terms of slavery, and in terms of not integrating properly, he had a lot of critical things to say, but nonetheless, he viewed America as a successful multicultural experiment. And he said, "Here, where we are, you take Lebanon. Lebanon is a failed state. It only works because we're able to pit various tribes and cultures and religions against each other. And so what really the truth is the people where we are, they want what America really has. And what we really hate America for is being that kind of a successful," it's a relative concept, "but that kind of a successful multicultural experiment," which I thought was pretty fascinating. So that what we misinterpreted as this deep kind of almost a religious hatred that we associate with this man, and we really do associate that in fact was really more, almost like a jealous resentment for an experiment that he wished could work where he is.

[00:58:21] Jordan Harbinger: It almost makes no sense to me, right? He wants to prove that this antiquated mindset of warring tribes and kind of like ethnic conflict that makes life literally just hell for so many people in that region. He wants to show that that's better than the melting pot salad bowl that he's envious of in the United States. Somehow that's even more disgusting than just blind religious hatred, which I could go, "Okay, this is like a stone age mindset of organized religion. He can't get out of it." No, he just wants, it's like saying, "Oh, this person is successful. I want them to fail miserably so that I feel better about myself," right? It's somehow even lower than just like, "Well, my God hates their God." That's more understandable than this line of nonsense.