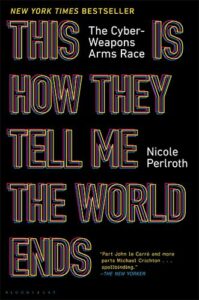

Nicole Perlroth (@nicoleperlroth) is an award-winning cybersecurity journalist for The New York Times and bestselling author of This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends: The Cyberweapons Arms Race.

What We Discuss with Nicole Perlroth:

- The startlingly simple reasons why most nation-states now resort to using cyberwarfare tactics before conventional weaponry in acts of aggression — to increasingly devastating effect.

- How industries are so interconnected that there’s almost no way for a cyberattack to target one victim without endangering countless others on all sides of a conflict (which is why you may have Putin to blame if there’s a Cadbury chocolate egg shortage next Easter).

- Why leaving the security of 85 percent of its critical infrastructure up to privatization makes the United States especially vulnerable to cyberwarfare attacks.

- The massive amount of intellectual property that’s been lost to hackers — from the formula for Coca-Cola to information that would allow China and other rival nations to catch up with the United States in the nuclear arms race.

- What Nicole believes the US should do to push back against these threats and the governments that perpetrate them — and ensure that it’s not inadvertently one of them.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

On this episode, we talk to award-winning New York Times cybersecurity journalist Nicole Perlroth about what she discovered while doing the research for her bestselling book, This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends: The Cyberweapons Arms Race. Here, we’ll discuss why cyberwarfare tactics beat conventional weaponry when a nation-state really wants to cause the most damage while risking little of its own citizens’ lives and resources, why the United States is playing with fire by leaving the security of 85 percent of its critical infrastructure in the hands of private companies, why the globally interconnected nature of modern industrial supply chains makes a surgical strike against one enemy likely to result in catastrophic collateral damage to all sides, how prepared the US is against existing threats (and how it can do better), and much more. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

Miss the interview we did with sleep doctor Matthew Walker? Catch up with episode 126: Matthew Walker | Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams here!

Thanks, Nicole Perlroth!

If you enjoyed this session with Nicole Perlroth, let her know by clicking on the link below and sending her a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Nicole Perlroth at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends: The Cyberweapons Arms Race by Nicole Perlroth | Amazon

- Nicole Perlroth | Twitter

- Nicole Perlroth | The New York Times

- How Does Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) Work? | Merchant Fraud Journal

- Colonial Pipeline Hack Reveals Weaknesses in US Cybersecurity | The New York Times

- Russian Cyber Threat: US Can Learn from Ukraine | Atlantic Council

- The Untold Story of NotPetya, the Most Devastating Cyberattack in History | Wired

- How Russia Used Solarwinds to Hack Microsoft, Intel, Pentagon, Other Networks | NPR

- Petya Cyber-Attack: Cadbury Factory Hit as Ransomware Spreads to Australian Businesses | The Guardian

- Who Are the Shadow Brokers? | The Atlantic

- Malware Naming Hell: Taming the Mess of AV Detection Names | G Data

- Prolonged AWS Outage Takes Down a Big Chunk of the Internet | The Verge

- Texas Power Failures Highlight Dangers of Grid Attacks | AT&T Cybersecurity

- A Hacker Tried to Poison a Florida City’s Water Supply, Officials Say | Wired

- Russian Trolls Promoted Anti-Vaccination Propaganda That May Have Caused Measles Outbreak, Researcher Claims | Newsweek

- Measles Outbreak: Anti-Vaccination Misinformation Fueled by Russian Propagandists, Study Finds | Oregon Live

- US Officials: Russia Behind Spread of Virus Disinformation | Voice of America

- Hacker Lexicon: What Is a Zero Day? | Wired

- What Is The Current State of Zero-Day Exploit Market? | LIFARS

- The Strange Journey of an NSA Zero-Day — Into Multiple Enemies’ Hands | Wired

- Is Huawei a Security Threat? Seven Experts Weigh In | The Verge

- How the CIA Used Crypto AG Encryption Devices to Spy on Countries for Decades | The Washington Post

- Here’s What Russia’s SVR Spy Agency Does When It Breaks into Your Network, Says US CISA Infosec Agency | The Register

- Pegasus: Who Are the Alleged Victims of Spyware Targeting? | BBC News

- If Saudi Arabia Did Hack Jeff Bezos, This Is Probably How It Went Down | Wired UK

- Mexico Says Officials Spent $61 Million on Pegasus Spyware | PBS Newshour

- Spyware’s Odd Targets: Backers of Mexico’s Soda Tax | The New York Times

- An Israel-Based Firm’s Spyware Was Found on Activists’ Phones | NPR

- UAE Government Hackers Targeted FIFA and Qatar 2022 Execs, Says Report | Inside World Football

- UAE Spies Monitored Michelle Obama, Sheikha Moza Emails: Report | Al Jazeera

- Saudi Operatives Who Killed Khashoggi Received Paramilitary Training in US | The New York Times

- The Million Dollar Dissident: NSO Group’s iPhone Zero-Days Used Against a UAE Human Rights Defender | The Citizen Lab

- North Koreans Stole $100M from Crypto Firms, US Alleges | CoinDesk

- Cybersecurity Questioned After Wolf Creek Nuclear Hacking | Think Energy

- Russia, US, and Other Countries Reach New Agreement against Cyber Hacking, Even as Attacks Continue | The Washington Post

- A US-UK Hacking Probe Offers a Fresh Approach Against Russia | Atlantic Council

- ‘They Are Hair on Fire’: Biden Admin Mulling Cyber Attacks Against Russian Hackers | CNBC

- Social Engineering: The Art of Human Hacking by Christopher Hadnagy | Amazon

- Jenny Radcliffe | Cat Burglar for Hire | Jordan Harbinger

- An Unprecedented Look at Stuxnet, the World’s First Digital Weapon | Wired

- A Timeline of Edward Snowden Leaks | Business Insider

542: Nicole Perlroth | Who’s Winning the Cyberweapons Arms Race? (Episode 542)

Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:03] Nicole Perlroth: Cyberwar isn't targeted. Cyberwar can take all of us down at a few clicks, but we're not acting like that. A lot of nations are engaged in developing these offensive capabilities, but they don't understand that the collateral damage is usually their own citizens or their allies or businesses.

[00:00:27] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We have in-depth conversations with people at the top of their game, astronauts and entrepreneurs, spies, psychologists, even the occasional four-star general, drug trafficker, or former Jihadi. Each episode turns our guests' wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better critical thinker.

[00:00:54] If you're new to the show, or you're looking for a handy way to tell your friends about it, we've got starter packs. These are collections of your favorite episodes, organized by topic. That'll help new listeners get a taste of everything that we do here on the show. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start to get started or to help somebody else get started with us. Of course, I always appreciate that.

[00:01:12] When I was a kid, I used to love finding bugs in software. I would be on a bulletin board system and I'd figure it out that some little ASCII color coding thing could crash the entire software and I'd report the bug to the sysop, the system operator. And I remember one time I did it and the sysop called the police and the police called my parents and they didn't really know what was going on, but my parents thought I was going to get in trouble. And you know, that just made me have a vendetta against this guy. Is it weird that I'm still mad about it? But law enforcement never really dissuaded me from hacking or from anything else. I later went to a hacker conference called DefCon and I found out how easy it is to get into our power grid. These scatter systems that mess with air traffic control and water and power using transponder hacking to trick aircraft. I mean, it really is just scary how quickly you can mess things up. If you are a bad actor. We regulate weapons and arms sales, and we work hard not to allow the proliferation of nukes, but we do nothing to stop the spread of what are called zero-day exploits and other hacks discovered in critical systems.

[00:02:17] My guest today, Nicole Perlroth, literally wrote the book on cyberwarfare. Today, We'll talk about why this is so dangerous, why we're not doing really anything about it, how it's being misused, both in the United States and abroad. We'll talk about hackers who forged documents, bride people hack computers, both domestically and abroad for money, white hat, black hat, and everything in between. We'll talk about massive attacks on Google from China and how nation-states are using cyberwarfare before pretty much any other weaponry these days. China has stolen enough IP from the Western world for the next decade, including the formula for Coca-Cola, Benjamin Moore paint, plans for the F35, and has stolen enough info to catch up with us in the nuclear arms race. But that might not be all we have to worry about right now. Today, we'll explore the cyberwarfare going on these days, how we're being attacked by our enemies on the regular, and how ready we are for the next catastrophic cyberattack against the west and/or the United States.

[00:03:11] And if you're wondering how we managed to book all these great authors, thinkers, and creators every single week, it's because of my network. I'm teaching you how to build your network for free over at jordanharbinger.com/course. And by the way, most of the guests on the show already subscribed to the course. Come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong. Now, Nicole Perlroth.

[00:03:33] The US is engaged in large scale cyberwarfare. And it seems like our critical infrastructure is more or less — I won't say undefended, but kind of undefended at the moment. How accurate would you say that statement is?

[00:03:45] Nicole Perlroth: That's incredibly accurate. You know, the statistic everyone throws around, although no one's ever actually furnished any proof that this is true, but it feels largely true. It's that 85 percent of our critical infrastructure is owned by the private sector. And the government has no say as of this moment over how secure or not secure it is. We leave it to every company to basically fend for themselves. And now, you're seeing ransomware attacks that are taking out pipelines and the food supply that just come down to a lack of two-factor authentication and bad password management. That's all it takes.

[00:04:26] Jordan Harbinger: For people who don't know, two-factor authentication is like when I'm trying to log into my bank and it goes, "Hey, we just sent you a text. Making sure that it's you please type in that four-digit, six-digit code." And there are people that are in control of like oil pipelines, power grid systems, water treatment plants that are like, "Eeh, I don't want to deal with that. I'm just going to use my — I've been using the same password for 20 years. Why change it now?" Right?

[00:04:50] Nicole Perlroth: That's right. I mean, even the Colonial Pipeline, you have to give them a little more credit and that it came down to some employee who'd come and gone — I don't even know how long they'd been gone — still had an active account with access to their network. And that account hadn't been used for a long time and didn't have two-factor authentication turned on. So all it took was someone getting his stolen password, seeing he worked at Colonial Pipeline, trying to get into the network and there being no obstacle to them doing so. And because Colonial Pipeline's network administrators weren't paying attention to some old employee's account. They weren't paying attention to the attack when they came in and started mucking around their systems and then deploying ransomware that held their data hostage in such a way that they couldn't actually see where gas was going off the pipeline. It's not like the ransomware hit the pipeline itself, but they're a business and they couldn't charge customers because their billing systems had been held hostage. So they took the step of shutting down the pipeline. So basically because they had this old employee account, that didn't have two-factor authentication turned on, an entire pipeline that supplies nearly half the jet fuel and gas and diesel to the east coast was held hostage. And all it took was this old employee with a stolen password that didn't have two-factor authentication turned on.

[00:06:11] Jordan Harbinger: And that seems glaringly — it's dangerous for that level of access to be sort of, it's kind of like leaving a gun in a room you never go in and you go, "Well, we never go in there." "Well, okay, but your kids are playing in the house." "Yeah. But I mean, I'm just never who would open that drawer.

[00:06:26] Nicole Perlroth: Right.

[00:06:26] Jordan Harbinger: And it's the same kind of thing, but we're thinking, "Ooh, but nobody has — it's kind of a tricky drawer. It's got—" "You know, there's a key lock. Where's the key?" "Oh, we leave it in the key chain with the house keys. They're not going to open that drawer." It's sort of the same thing, except for, we would never think that that gun is secure, but we think, "Well that employee's gone. So no one's going to log into that account." Well, okay, no one, nefarious. I guess to their credit sort of Colonial Pipeline, the oil pipeline that was shutdown for those of you who don't know what we're talking about. They shut that down themselves because they were worried about what might happen because the other elements of their system were compromised. And that's kind of a whole other discussion about, was that the best way to have your systems connected like that. And to their credit, they shut it down before somebody could do something really horrible, but not all cyberattacks have ended with just a rush on gas that ended up being a big nothing burger.

[00:07:19] We saw a massive Ukrainian cyberattack by Russia. So take us through that a little bit. And also why do this? You know, what's the message to Ukraine from Russia here by doing this?

[00:07:30] Nicole Perlroth: So the attack by Russia and Ukraine, and there have been several noteworthy attacks. One of the most famous was when they actually turned the power off to a large section of Western Ukraine for a few hours. And then a year later came back and did the same thing to their capital, Kiev, for a couple hours. That was a big one, but the one you're referring to is the one that security people call NotPetya. And it's a horrible name and it's worth just lingering on it for a moment. The reason they called it NotPetya was because it looked like a huge ransomware attack that looked like Petya ransomware, but it wasn't ransomware because there was no way for the victims to pay a ransom and get access to their data back. It was actually just an attack of destruction. So what happened was sometime around 2017 or earlier Russia breached a company. That's basically like Ukraine's TurboTax. Actually legally, most government agencies and banks and large corporations in Ukraine are required to use this tax software. That tax software company is run by mom and pop just outside Kiev, who never thought that their little tax software company could be used as a nation-state weapon. But that's what happened.

[00:08:45] Russia's preeminent hackers from the GRU, their intelligence agency, came in, compromised the tax software company, got into the software update. So that when all of these Ukrainian companies downloaded the latest, greatest version of this tax software, they weren't just downloading the tax software. They were downloading a GRU backdoor. And once they were inside their GRU unleashed, what was essentially a digital weapon of destruction. It looked like ransomware, which is just code that holds your data hostage with encryption until you pay up, only there was no way for the victims to pay. So all of a sudden, all of these Ukrainian government agencies couldn't access anything on their network. They can access email or anything else. They had to hop on Facebook to communicate with the country to say we're still standing, but it also hit railways. People couldn't get tickets on trains. It hit the postal service. People are still not getting pension checks that they were owed back in 2016, 2017. It held up the radiation monitoring systems at Chernobyl, the old nuclear site.

[00:09:58] So suddenly, the people at Chernobyl couldn't see how much radiation was leaking out of that blast site, but it also hit any company that did any business in Ukraine, even if they had a single employee working remotely from Ukraine, they were caught up in this attack. So it hit FedEx, FedEx suffered $400 million in damage from this attack. It hit Pfizer. It hit Merck. Merck's vaccine production systems were held up in this attack. It actually had to go tap into the CDCs emergency supplies of vaccines that year. It hit Cadbury's eggs chocolate factories in Tasmania. You name it—

[00:10:38] Jordan Harbinger: Dear Lord, no!

[00:10:39] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. And so it ended up being the most costly cyberattack known to man. It was a $10 billion in damages. Although we think it might've been worse because a lot of victims didn't even report their damages, but it was really a prelude in some ways to a lot of the attacks we're seeing now. You know, if we had been paying closer attention to how that attack happened in the United States, we might have been a little bit more prepared for the SolarWinds attack that we're still unwinding right now. Where another Russian hacking group — this time, less of a destructive actor, thank God — broke into SolarWinds, which is a Texas company that provides software to more than 400 of the Fortune 500 and to all of our preeminent federal agencies like DHS and the Treasury and the Department of Justice and the Department of Energy and our nuclear labs got into their software update. And all of a sudden, most government agencies downloaded this Russian backdoor. And we still don't know no the extent of damages as from that attack. We still don't know just how deep the Russians are into our government systems, but they also got into some of our electric utilities. We don't know what they plan to do with that access.

[00:11:54] So this is where we are now. We are seeing a tax come in through the software supply chain. And for years, people have been talking about this threat. But now suddenly they're asking the right questions, which is how do you trust that any of the software you're using is secure and not a Russian Trojan horse.

[00:12:14] Jordan Harbinger: Especially when you're updating. I mean, I update my apps all the time thinking, "Oh I'm in the latest version. I'm on the most secure version," but if there's some fake update that I install now I'm on the least secure version of that software that's ever been created. And it might disable my ability to update to a patch. I mean, it's really hard to say. I assume they did that. They went, "Well, okay, if they find out about this, we don't want it to then check the server for the latest undo. We want it to just not work anymore." And now you're in this sort of zone where you're going, "How do I manually update my TurboTax, my Ukrainian TurboTax?" Okay. I have to delete it. Then I have to download the fresh version. That's off their website, which I've never been to and find that, and then enter my code that I haven't looked at in three years because I bought it ages ago. And you're doing that hundreds of thousands of computers or millions of computers at the same time.

[00:13:04] Nicole Perlroth: Right.

[00:13:04] Jordan Harbinger: And it's pervasive. It does strike me as sort of like tragically comical, that vaccine companies are reporting these losses, shipping companies are reporting these losses, and then Cadbury's like, "Hey, and we can't get any of those chocolate eggs out. Like, we're going to be way behind this Easter for these little eggs." Just to nobody points the finger — blame Putin. Okay. Don't look at me.

[00:13:24] Nicole Perlroth: Right. And the only reason I ever bring up Cadbury in my list of NotPetya victims and I always bring it up is just because I want people to understand that we're so interconnected now that a targeted attack between Russia and Ukraine doesn't even exist anymore because we're so connected that something — you know, Russia decided to aim at Ukraine to basically take them offline ahead of their independence day — would actually cause disruption to a chocolate factory in Tasmania is really the best visual you get when you try and understand that cyberwar isn't targeted, cyberwar can take all of us down at a few clicks, but we're not acting like that. A lot of nations are engaged in developing these offensive capabilities, but they don't understand that the collateral damage is usually their own citizens or their allies or businesses. And what's really interesting from that attack is, you know, I mentioned some of the figures of damages, FedEx $400 million, Merck, I think at $600 million, when they tried to go get that money back from their insurers, because they had cyber insurance, their insurers said, "Uh-uh, you know, we have this tiny little clause in your policy. That's a war exemption clause. And it says that if you are collateral damage in a war, we don't have to pay out. And in this case you were collateral damage in Russia's war on Ukraine. And so we're not going to pay you out." And those lawsuits are ongoing, but American companies are on the hook for those damages.

[00:14:58] Jordan Harbinger: That is crazy because of course, it is a war damage, but also it's like, "Well, when I signed that, I thought you meant if there's a drone strike and it knocks out part of our headquarters, you're not going to pay for that. Not an actual cyber intrusion, which is the whole freaking point of the insurance." And the insurance company's argument is, "No, no, no. We're insuring you for when a kid comes into your office and installs some spyware and knocks out 50 of your computers and you have to replace them, or you have to scrape that data. We're not paying you when the GRU, the Russian military sort of hacker intelligence unit target something and your collateral damage."

[00:15:32] And so now there's probably a whole different type of insurance industry out there with much higher premiums that says, "Oh yeah, we'll insure you against that for $350 million or more on an annual basis, depending on how big your company is." You know, it's like this massive — now you're paying as much for cyber insurance as you are for insurance and all your FedEx delivery trucks at this point because the damage is equal or greater.

[00:15:55] Nicole Perlroth: Well, that's right. I mean, I and you live now in the wildfire zone and my neighbors are getting notices that their insurer will no longer cover fire insurance on their properties anymore. And I think that's what's happening now with cyber insurance. Yeah, sure, they'll still cover Pfizer and Merck and FedEx, but their premiums are going to be astronomical and there's going to be all sorts of fine print in there that says, "If you're a target of this kind of attack, we don't have to pay out." And so this is something businesses are reckoning with.

[00:16:28] Now, the good news is that cyber insurance companies will you say, "Okay, we'll underwrite you, but you need to have a much higher baseline of cybersecurity. You need to have two-factor authentication installed. You need to be patching your systems. We need a clear idea of what's in your network and how well secured that software is. We need to know that you have strong password management or your employees are using password managers, all of that." And so in some ways it's creating market incentives for these companies to raise the bar.

[00:17:00] But there's another thing about that NotPetya attack which I failed to mention, which is the reason it was so cataclysmic, why it destroyed so much is because it was sailing on a stolen weapon from the national security agency. So just a few months before Russia launched that attack on Ukraine, someone — we still don't know who they are. They called themselves the Shadow Brokers, had hacked the NSA and had started dribbling the NSA's best kept code and hacking tools online. And one of the tools that they dumped was some code that exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft Windows that allowed their malware or code to spread automatically across a network instead of a hacker, having to manually infect one computer after another, the NSA's tool essentially allows them to automate this attack.

[00:17:55] So after that was dumped online, North Korea picked it up for a ransomware attack. That was pretty bad, but fortunately the North Koreans had made some mistakes in their code and someone was able to neutralize it pretty quickly. And then Russia baked it onto its NotPetya attack, which is you saw their code sail around the world in the way it did and reaped that much destruction on companies, including American companies. And there's been no accountability for that. And people don't even realize that all of those damages were enabled by an NSA digital hacking tool.

[00:18:31] Jordan Harbinger: NotPetya attack — by the way, how do people name these things? Like WannaCry, Petya, NotPetya. How did the names come up?

[00:18:38] Nicole Perlroth: Okay. It's a huge point of frustration for me. If I run for president, it's going to be like a single platform which is, cut out the ridiculous names for these attacks and for these nation-state groups, because it's gotten crazy like CrowdStrike as a security company and they named Chinese attacks, something Panda, Russia something bear. You've all these names for these groups like Fancy Bear and Berserk Bear and every cybersecurity company's naming convention is different. So anytime we call out these groups, it's like, Nobelium AKA so-and-so bear, AKA APT 2372, you know, it's so frustrating. But usually the way it goes with malware ransomware is that it's after some word in the code. So the North Korea attack that I mentioned was called WannaCry because there was some little snippet of code in their ransomware that said something like W-N-A-C-R-Y, you know, something like that. But really it'd be great if we could get some central naming authority to avoid some of these ridiculous names and the confusion.

[00:19:47] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I figured there was something to that with the code. The NotPetya attack, something like 80 percent of Ukrainian computers had to be wiped clean because of this. So that's massive. And it sounds like what we're worried about is not just how much damage that can cause, but the fact that that might just be a dry run for something even larger. I mean, okay, you went after Ukraine, it went and destroyed a bunch of data, $10 billion in damage. What happens now, when you go after Canada and Mexico and the United States and Germany? Which you can easily do. I mean, I would imagine, it's not a huge squad of people required to pull off an attack like this against a nation-state. They chose Ukraine because they knew they wouldn't have any consequences to pay as a result, most likely.

[00:20:30] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. Well, it's pretty interesting. And I didn't really, I couldn't really wrap my head around this until I went to Ukraine and met with all the people who did forensics inside Ukraine on not just the NotPetya attack, but several of the attacks I mentioned leading up to it. You know, the attacks that took out the power, there were attacks that were aimed at Ukrainian media companies. For years, they'd been shelling Ukraine with all of these different kinds of attacks, but what was clear to the people who did forensics is that this was Russia really experimenting. This was their Petri dish. This was them trying out one method here, one slightly different method there, basically, like the scientific method of hacking. And so their theory on the ground there is that NotPetya, you know, it was designed to look like ransomware, but there was no way for people to pay the ransom. And that really, it was just a destructive tool. It was a way for Russia to wipe the slate clean, to erase any trace of everything they had done before that, so that no one would be wiser to the capabilities they do have. And what they said was we believe that we weren't the ultimate target. We believe that we were spring training. We believe that you, in the United States, in the west are the end target here.

[00:21:46] But when it comes your way, we should mention that it will be so much worse because we are actually not that digitized here. We still run our elections on pen and paper. Our power systems are still pretty archaic. NotPetya didn't take out the power across the whole country. It didn't touch our nuclear plant. But when it comes for you, there is a high likelihood that it will do a lot more than $10 billion in damage. And it will take a lot longer for you to get your systems up and running because you're so much more virtualized. And by the way, it doesn't seem like you're that secure either. So it was a wake up call, but we're not really treating it. Like it's a wake up call. We didn't change the fundamental ways we do business after the NotPetya attack. Most Americans have never even heard of the NotPetya attack.

[00:22:37] Jordan Harbinger: They wouldn't even need to do much to take down — to do billions of dollars in damage to the United States. I mean, if you took down Amazon web hosting, which a lot of people think, oh, Amazon, you buy things there that backbone of Internet hosting, there goes almost all of the services that you use, or if you took a chunk out of — I mean, remember when Gmail's down for like a day and people are like, "What the hell? We can't do any business?" What if you took down the Outlook and Amazon, or you just stopped airline traffic for a day or a week, like the Iceland volcano, except for the United States. And all you need to do — that's not even like kill people type of damage, that's just a massive, expensive inconvenience.

[00:23:19] Now, you're talking about what happens if they shut off the power in the south, in July when it's a hundred degrees outside and no one can turn on air conditioning or a fan. And the phone system doesn't work because the cell towers are down. So you can't even call 911 if you're passing out or you need an ambulance. Like that kind of thing could be done by a few people relatively easily, because a lot of those SCADA systems, I think they're called her from like the '90s, those power grid systems. And I remember talking with somebody who worked there a long time ago and they are people that go, "Oh yeah, our systems are so safe. They're buried underground. You have to go in this tunnel. And the tunnel is flooded half the time to get there." "Well, how do you control it?" "Oh, we hooked it up to a telephone line. I can log in from my phone." "Okay. So you did that and you never ever go down there for local access. You don't think anybody else can do that." And it's really shocking because these guys do connect the system to the phone line, it's like the young intern figured out how to do that. They didn't hire CrowdStrike to make their systems accessible remotely. They just freaking plugged it into Zoom, basically. It's just really, really pathetic a lot of the ways that these things have been made accessible.

[00:24:32] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. Well, you know, we don't even really have to use hypotheticals because there was a situation over the winter when Texas power went out. Was it S Scott? Is that the name of the company?

[00:24:44] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. That was it.

[00:24:44] Nicole Perlroth: You know, they went out and everyone in cybersecurity said, "Oh gosh, is this the attack we've been waiting for?" "Nope. It was just due to an underinvestment in winterizing." If they're making that level of, or lack of investment in winterizing, what do you think their cybersecurity posture is? And look at what happened. I mean, people were not, they didn't just lose power in the middle of this storm, they lost access to their water because their pipes were frozen. I mean, that's really what it would look like. Only in this case, you know, Russia might not turn it back on. They might make sure that the power stayed up. The one I actually worry about the most is water, because at least we've sort of wrapped our heads around a threat to our power supplies, but we haven't really wrapped our heads around the threat to the water supply. And most of the water or treatment facilities here in the United States serve communities of less than 10,000 people. And they barely have an IT guy on staff let alone a cybersecurity expert.

[00:25:51] And just the day my book came out, actually there was a hack on a water treatment facility. In Oldsmar, Florida, just outside Tampa were hackers got in remotely into the water treatment facility because they'd been using a decade old version of Microsoft Windows that hadn't been patched in years and they didn't have two-factor authentication turned on and they hadn't even thought about this scenario, but a hacker was able to get into their chemical controls and up the level of lye, L-Y-E, and the water from something like 1100 parts per million to 11,000 parts per million, which is enough to send everyone to the hospital in the middle of COVID when hospitals are already under strain and oh, by the way, they did it on the Friday ahead of super bowl weekend in Tampa.

[00:26:36] So thank God, some engineer was sitting at his computer and happened to watch his cursor move around and catch this thing in action but you know, in most cases there wouldn't have been an engineer sitting in front of their computer, watching that happen. And you know, it's just at a wedding last weekend and right next to our hotel was this little water treatment facility. And it was like, there is no way there is an IT guy sitting there on prem watching to make sure no one's mucking around with their chemical controls. And I guarantee you, there's a very easy way for someone to remote into their system and up the level of caustic chemicals in the water. So the scenarios are endless and we keep having these close calls, but we're still not changing the way we secure our critical infrastructure.

[00:27:24] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Nicole Perlroth. We'll be right back.

[00:27:29] This episode is sponsored in part by Boll & Branch. Now that I'm older, I prefer not to own a ton of stuff, but everything I do own and use, I want exceptional quality. And I also care whether it's made in a sweatshop situation or fair trade. Those children's tiny fingers. They do make the softest sheets, but I don't buy those anymore. And neither should you. I recommend Boll & Branch. It was started by a husband and wife team that wanted to create a textile company that cared about the details that would make their products last. And every part of the manufacturing process follows some of the most rigorous fair trade practices, which means safer working conditions and fair pay over industry standards. Moreover, we spend about a third of our life in bed, if you're like me, half. So it's important to feel good in comfortable sheets. You'll feel the difference in their best-selling a hundred percent organic cotton Signature Hemmed Sheets. I look forward to slipping into bed every day in my sheets, so smooth and soft. Boll & Branch stands behind their products and honors a 30-night worry-free guarantee if you're unsatisfied.

[00:28:20] Jen Harbinger: To experience an entirely new standard of comfort, visit bollandbranch.com. Get 15 percent off your first set of sheets with promo code Jordan. That's B-O-L-L-andbranch.com promo code JORDAN.

[00:28:32] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Sennheiser. If you bump into me, I'm probably wearing earbuds. I basically live in them. I'm working out to music or I'm walking and listening to audiobooks all day. When it comes to earbuds, it's all about sound quality. I've never really truly found ones that have blown me away until I tried Sennheiser's Momentum True Wireless 2. They make the best earbuds. If you care about sound quality, like I do, of course. For the past 75 years, Sennheiser has put sound first. We use their shotgun mics. I've been using Sennheiser mics forever. So I know they make great stuff. The noise canceling on these earbuds is amazing. You can dive into your favorite podcasts, hint, hint with their noise cancellation. And my absolute favorite feature is the up to 28-hour battery life. That's incredible as longer than a day, as you know, you can rock them on a flight, you can bring them on a trip. You don't need to keep recharging these things. They are really amazing.

[00:29:21] Jen Harbinger: Why settle for anything less than great sound? Come hear the difference with Sennheiser. Right now for our first 100 listeners who go to sennheiser.com/podcast and use promo code HARBINGER, you'll receive 15 percent off the Momentum True Wireless 2 earbuds or any of their amazing headphones. That's 15 percent off when you go to S-E-N-N-H-E-I-S-E-R.com/podcast, and use our promo code HARBINGER.

[00:29:44] Jordan Harbinger: Now back to Nicole Perlroth on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:29:49] I would imagine that that software that runs those plants, it's all the same stuff. It's all the same version of the same stuff. It all runs on Windows. Like you said, the Windows might not even be patched. That sounds like they just got remote access to Windows and then they use the software like you can do with a screen share on Zoom or any other remote software. Imagine if somebody found out how to — I'm sure they already did find out how to remotely access this software plain and simple because they make these things easily accessible so that, "Hey, your IT guy, oh, he's a consultant. He lives off site." "Hey, there's something weird going on with our software." They give him a call. He logs in remotely and handles it. That is absolutely not secure.

[00:30:28] There's like you said, there's probably one guy there just to make sure pipes aren't exploding and they're on their iPad watching Netflix. And they're just looking for giant spurts of water squirting out. They're not sitting there going, "Oh, that seems like a chemical imbalance on system number seven. Let me go look at that and inspect that." They probably don't even have anybody qualified onsite to even do that at any given time. So that is terrifying, especially because you can log in and do that to a thousand small town water systems, probably all at the same time or within a few hours before anybody figures out anything and they can unplug the Internet. I mean, the amount of damage is massive. And then you have no idea who did it in the first place. I mean, you can point fingers, but that's pretty much it.

[00:31:11] I remember reading that in Ukraine, Russia pushed a lot of the anti-vax stuff that sounds very familiar here. They tested that on the Ukrainian population said, "Hey, the MMR vaccine causes autism." And then there was a massive measles outbreak or something like that, right? Am I close here?

[00:31:27] Nicole Perlroth: Yes, you're close. I mean, it was really disturbing. And again, I cannot wrap my head around this until I actually went to Ukraine, but I met with officials at the embassy and I was there to talk about cyberthreat hacking threats but they didn't even have time to think about cyberthreats because they were so focused on Russian disinformation and Ukraine had at that very moment, there was this crazy measles outbreak that I had actually spread to Hasidic communities in New York, because some of them do this pilgrimage to Ukraine every year.

[00:31:58] But a lot of it, Ukraine has a disinformation minister or something. We don't still have here in the United States, but I met with him at the time. And he said, "Yes, they tracked a lot of it down to Facebook pages targeted at young Ukrainian mothers where you Russian trolls were flooding the comment section, trying to legitimize the vaccination debate, and seeding doubts among Ukrainian mothers that measles vaccines caused autism or was some, you know, nation-state tool of control. And so a lot of young mothers weren't getting vaccinated. Meanwhile, back in Russia, the vaccination rates were nearing a hundred percent. Whereas in Ukraine, they were dipping below 50.

[00:32:40] It didn't even hit me at the time because this was 2019, that a year later, less than a year later, we would have a global pandemic. But sure enough, here we are in the middle of this global pandemic and the biggest threat right now is vaccine hesitancy and oh, yep, some white papers are just now coming up that are tracing a lot of disinformation related to the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines to Russian troll networks. And they're playing out on Facebook. They're playing out on social media and this is where we are now.

[00:33:12] Jordan Harbinger: That is, of course, terrifying because it affects the public health of the entire country. And yeah, the joke is really on us because when you look at vaccination rates in Russia, "Oh, well, why are they so high?" "Oh, they have an oppressive government." Okay, but they're obviously not doing the same type of disinformation that they are over here. And of course, it's using our own sort of information, freedom against us, and that's a whole different probably podcast here, but I want to go back to what you mentioned before the Shadow Brokers hack and what this means, the gravity of it. I don't think most people know what zero days are, why they're valuable. Can you take us through that a little bit? Because this is one of the main reasons that we're having so many cyberattacks, correct?

[00:33:51] Nicole Perlroth: You know, it isn't, it is and just a backup. And I promise this is the most technical part of our conversation today, but what is a zero day? So a zero day is a flaw in software that the software maker is not aware of. And the day someone discovers it that's day zero or zero day because they've had zero days to fix it. And until they can fix it, everyone who uses that software is vulnerable to hacking. So just to take the most simple example, let's say I'm a hacker and I find a flaw in your iPhone's iOS software, and I can write a program to exploit it. So that flaw is called a zero day. The program to exploit it's called a zero-day exploit. And if I create a good program, I can use it to read your text messages, track your location on your iPhone, access your phone calls, use your camera without your knowledge record, all of your surround sound and conversations, your calendar appointment. That's basically everything a spy agency could ever want or need.

[00:34:53] And so there is a market where governments are not regulators, but governments are customers. The US government is one of the top customers in this space and they will pay hackers to sell them those zero-day exploits. The going rate for the zero-day exploit I just described in your iOS software is $2.5 million. US government brokers will pay you $2.5 million to sell them that exploit with the condition that you not tell anyone about it, because the minute you tell someone or the minute Apple finds out about it, they'll patch that underlying zero day, you'll get one of those annoying prompts on your phone to update your software. And suddenly that $2.5 million capability turns to mud.

[00:35:36] So there is a long history here since the '90s of US government agencies paying hackers, both in the United States and abroad to sell them these zero days and the code to exploit them, to add to their stock files. So I started writing this book about this because I was just fascinated by the moral hazard and the security dilemma baked into that marketplace. You know, we are all using the same software today. Three decades ago, when these programs started, this marketplace launched. We were all using different software. China was using Huawei. We were using Oracle and Cisco for the most part. Three decades later, Huawei is a glaring exception, but we're all using the same technology. We're all using Android phones and iPhones and Windows. Whether you know it or not, you might not have a Windows PC, but it's in the power grid and your water systems and your pipelines. And same for industrial systems, Siemens software, Schneider electric software, that's pretty much the market leaders when it comes to industrial systems.

[00:36:40] So when the US government finds a zero day in that software and holds onto it and make sure that it doesn't get fixed, it means that most Americans in our critical infrastructure, more and more so are left vulnerable. So I was fascinated by this. I never, in a million years imagined that the NSA's own stockpile of zero-day exploits would get hacked by someone — we still don't know who they are — three, four years later dumped online so that our adversaries like North Korea and Russia would pick them up and use them in these global destructive attacks. But that is precisely what happened. Now, the zero day that was used by North Korea and Russia was called EternalBlue at the agency at the NSA.

[00:37:27] I do know from reporting that it was developed in house. This is not something that they secured off the market, but that marketplace is alive and well today. Actually the going rate for that iOS zero-day exploit I described earlier, you can actually get more of these days if you sell it to a broker based in Abu Dhabi called Crowd Fence. They're offering $3 million or $3.5 million for that same one that US agencies will pay $2.5 million for, and in essence, what that market does is it closes the capabilities gap.

[00:37:57] So three decades ago, the US was still the top player in the space. We were worried about Russia. We were worried about China, not so much because China matched our capabilities. We're still sort of the top dog. No one's pulled off the same level of attack that the United States and Israel pulled off several years ago, but they were just so prolific with their attacks that we were worried about that.

[00:38:19] What the market has done is it's closed this capability's gap. So that countries that have had very little in the way of authentic capabilities or engineers with the skills to pull off these attacks can now tap into this market and buy things off the shelf that years ago they would have had to develop in-house. And that's why I focus on the zero-day market in the book, but you know, that is advanced nation-state level cyberwarfare.

[00:38:45] Unfortunately, on the defensive side, a lot of the attacks we're seeing right now don't come in through zero days. They come in through just the lack of basic cybersecurity hygiene. They come in through stolen passwords and a lack of two-factor authentication. 80 percent of the ransomware attacks we're seeing right now, come in through a combination of a stolen password or a phishing email, and a lack of two-factor authentication. Although as terrifying as that, just last month, the Department of Homeland Security warned that there is a new ransomware strain out there that does exploit zero days and does use zero days. And that's very scary because those are almost impossible to stop until you figure out what flaw they're using and how to patch it and get that patch rolled out to everyone and get everyone to actually implement that patch because these days, so many companies are too lazy to even run their patches on time.

[00:39:43] Jordan Harbinger: What about backdoors deliberately programmed into software? I mean, we've heard that, "Hey, don't use Huawei software, it's got a backdoor. China sniffed the traffic coming from any of your devices." You know, a lot of people say, "Oh, that's just BS. It's just non-competitive crap." But I would assume that there are backdoors deliberately programmed into many devices. I mean, why wouldn't there be, especially when you're talking about like industrial, supposedly secure networking devices. There's a big incentive for a company to accept a nice a hundred million plus dollar incentive or something like that to put something in there that's never going to get misused. We're only using this for national security, right?

[00:40:22] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. And there's a long history there. The most famous example was a Swiss company that offered encryption and they were called Crypto AG. And we learned later that they were getting paid off by the CIA and the NSA to put a backdoor into that encryption software because their encryption was used by countries that don't trust American software like Iran, Syria, North Korea, et cetera. And so the NSA basically went to them and said, "Use this backdoor. Put this backdoor in your systems. You'll be doing your country and ours a giant patriotic favor. We will cover your expenses." And that was in essence, the way that US intelligence agencies were able to spy on some of Iran's most sensitive systems for years before the Iranians discovered it and actually arrested one of Crypto AG's employees who had no idea that his employer was doing this. That was a long time ago.

[00:41:24] Now the people I interviewed for my book wouldn't speak directly to any of these operations, because obviously they're incredibly highly classified. But what they would say is that in the US intelligence community, there is a five-tier or six-tier system. And at the bottom are nation-states that have basically zero hacking capability, like we call them the script kiddies of nation-states. They might be able to pull off some silly denial of service attack. Although these days, they can tap into the market and buy some of their hacking capabilities off the shelf. Then in between there are countries that have the talent to pull off these attacks, they might not be able to pull off a sophisticated attack that would turn off the power somewhere, but they could basically fill up their capabilities gap by tapping into the market. And then at the top, there are countries that can hack into technology and place a backdoor into the software supply chain and use that sort of Crypto AG model to spy on their enemies. And at the very top is the tier six guys, the top dogs who can do that all at scale. And they said that is where the United States is today. We are at a place where we can plant backdoors into global technology so that we can spy on these systems at scale in real time.

[00:42:44] And I had the privilege, I guess you would call it of having a small slice of access to the Snowden document. And it was very clear from some of the NSA and the GCHQ documents that we were inside two of the leading encryption chip makers in the world. They never named the actual manufacturer, but they said, basically we have full capability to spy on anyone who uses this particular flavor of encryption chip. So we know that the United States and our closest allies in Five Eyes have been doing this for a very long time. And we never stopped to think that maybe our enemies would be doing the same to us, but that is an essence, what the SolarWinds attack is the one that we're unwinding right now. You know, it's not them planning a backdoor physically into the hard drives or the encryption chips. But they don't need to do that because they were able to get into this cloud application used by so many US government agencies and top cybersecurity companies and electrical utilities to do whatever they wanted.

[00:43:43] And the good news from that attack is that the actor was the SVR, which is really a traditional espionage, Russian espionage group. They're not the same actors that turned off the lights and Ukraine and launched the NotPetya attack. They're known for stealing emails and strategy planning documents and that kind of thing. The bad news is we know the SVR pretty well because they actually hacked the White House and the State Department between 2014 and 2015. And when I went and interviewed the guys who were brought on site to remediate and get the Russians out of those systems, they said, "We'd never seen anything like it, it was like hand to hand digital combat." It's not as if we would see a Russian hacker inside the state department's network and they would scurry away. They would stay and fight to keep their access. At one point, they even hacked investigators tools, the RSA NetWitness tool that they use to find further Russian backdoors and manipulated it. So it wouldn't find their backdoors.

[00:44:40] So that's the adversary inside our systems right now. And not only that they were inside our systems for nine months before a private company said, "I think we have a problem here." So it's going to be at least a year or more before we can stand up and confidently say we've eradicated Russian hackers from nuclear labs, the Department of Homeland Security, the Treasury, the Justice Department. And that's a real problem because, you know, maybe they don't pull off these destructive attacks, but we know that there's a lot of coordination between a lot of Russian nation-state hacking groups. And they could just as easily pass that access off to a group that is known for pulling off some of these more destructive attacks.

[00:45:22] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. If they have nine months of mapping out our network infrastructure and saying what works, where, and credentials and everything, they can just say, "We're done with this. We got the boot. But if you guys want to go in there and make a huge ass mess and detonate a cyber bomb on a nuclear facility. Here you go. Here's everything we know." Some of it's a little outdated, but the rest of it is probably still intact. We still know where all the facilities are. We still know what all the software they're using is with the exception of maybe the SolarWinds has a patch now, but everything else that the computers are still in the rooms they were in before. I mean, we're not rebuilding those systems from scratch. We're just trying to secure them. And any IP they stole, of course, is already gone. So that is quite arrogant of us to put a backdoor in hardware or software. And then think no one else is ever going to find this, especially when they might even be in the systems that we are using to plan the placement of those backdoors in the first place.

[00:46:15] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. And it really complicates the US response. You know, every time I cover one of these attacks, I post the story on Twitter and, you know, 60 percent of the responses are, "Why don't we just go shut off the lights in Russia already? You know, clearly, they're not deterred from these attacks. Time for us to flex a muscle and shut off the lights." Well, that really sounds good in theory, but the problem is that people don't realize just how vulnerable we are. So yeah, you know, how do you respond to SolarWinds? When number one, it's the same kind of attack the US government has been pulling off for years on adversary systems on Huawei and Crypto AG and all sorts of others that we don't even know about. Do we really want to take that kind of activity, that kind of traditional espionage activity, and say this is off the table? I don't think so. So because we do it all the time, we've been doing it for decades. We've just been doing it better. So it's harder for people to detect American stealthy supply chain.

[00:47:15] But the other thing is: how do you respond to an attack aggressively when you yourself are so vulnerable? And the language that I hear all the time is we live in the glassiest of glass houses. So yeah, we might have sharper stones than others. But our adversaries can just come back and say, "Hey, they just blew up this pipe," or, "Hey, they just turned off our lights." We have the right to respond proportionally, which means we can come hold up the Colonial Pipeline. Only in Russia, they have the luxury of basically outsourcing that kind of activity to cybercriminals or ransomware groups and say, "We had nothing to do with this." We don't have that luxury here. Any attack you see come out of the United States comes out of the NSA or cyber command or another intelligence agency. We don't have the luxury of saying, "Hey, Northrop Grumman, you go do this for us," or tapping the guy at Google on the shoulder at night and saying, "Hey, you're going to come and moonlight for us." So it's harder to hide these American attacks through these layers of attribution and plausible deniability. And that makes escalation that much more of a risk, particularly when we are so vulnerable.

[00:48:25] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Nicole Perlroth. We'll be right back.

[00:48:30] This episode is sponsored in part by Nuun. When you work up a sweat, dancing at a music festival or whatever, it's me working off my dad bod, you lose vital electrolytes and minerals that your body needs in order to keep moving and recover efficiently. Nuun Sport is optimized for hydration and mineral replenishment before, during, and after a workout. You drop a fizzy tablet into your water bottle to support your hydration, anytime, anywhere. Handy at concerts, festivals, flights because I'm sweating a lot on flights, I guess. Nuun Sport is made with only one gram of sugar and carefully sourced premium ingredients that are certified non-GMO, gluten-free, and vegan. Available in 13 delicious flavors, including fan favorite cherry limeade, which has an extra boost of caffeine.

[00:49:12] Jen Harbinger: To get your game-changing hydration, visit N-U-U-N.life/jordan and enter code JORDAN for25 percent off your first order.

[00:49:19] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Peloton. I've been home a lot, like a lot-lot, just like you have. And there are many like watching movies from the comfort of my own couch. And I can pause when I want, podcasting in my underwear, which is like something I've always done, but whatever, some things are just better at home, home sweet home. And Peloton delivers a workout experience that you'll never imagine is possible right in your own house. And better yet, I can create a full body workout that includes stretching to yoga to cycling, meditation, Pilates, whatever you want. Jen loves the dance cardio. One thing she likes, loves to do is high five everyone in achieving their milestones. I admit I get a little dopamine boost when I receive high fives too. The community aspect helps motivate, keep you going. When you purchase the Peloton bike, you get access to that live classes and thousands on demand. Plus access to the app to get you moving anytime, anywhere with a bootcamp between nap times or ride before brunch. You can seamlessly fit the Peloton into your life.

[00:50:10] Jen Harbinger: With the Peloton bike, there's nothing like working out from home. Learn more at onepeloton.com. New members can try Peloton classes free for 30 days at onepeloton.com/app. That's O-N-E-P-E-L-O-T-O-N.Com.

[00:50:25] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored in part by Progressive. What's one thing you'd purchase with a little extra savings? So a weighted blanket, a smart speaker, maybe some therapy, get a mattress here and there. I'm trying to get you to support our sponsors here, people. Well, Progressive wants to make sure you're getting what you want by saving you money on car insurance. Drivers who save by switching to Progressive save over $700 on average, and customers can qualify for an average of six discounts when they sign up. Discounts like having multiple vehicles on your policy, should you be so lucky. Progressive offers outstanding coverage and award-winning claims service. Day or night, 24/7 customer support, 365 days a year. So when you need them most, they're at their best. A little off your rate each month goes a long way. Get a quote today at progressive.com and see why four out of five new auto customers recommend Progressive.

[00:51:09] Jen Harbinger: Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. National Annual Average Insurance Savings by New Customers surveyed in 2020. Potential savings will vary. Discounts vary and are not available in all states and situations.

[00:51:20] Jordan Harbinger: Thank you so much for supporting the show. Your support of our advertisers keeps us going for all the links and all those promo codes that you hear on the show, those are all in one place. Go to jordanharbinger.com/deals. That's where everything is. No need to write anything down. Please consider supporting those who support us.

[00:51:35] Don't forget we've got worksheets for many episodes of the show. If you want some of the drills and exercises, main takeaways talked about during, they're all in one easy place. The link to the worksheets is in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast. Now for the rest of my conversation with Nicole Perlroth.

[00:51:53] You mentioned before the script kiddie country's buying nation-state capabilities. I looked this up this system called Pegasus. And I think — was it Saudi Arabia who essentially can send a text to like Jeff Bezos and they have full access to his phone? And I did that and they got some, I don't know, racy underwear photos of the guy that made it into the National Enquirer, I think. This is scary because I looked at Pegasus and I was like, "Well, how much does it cost?" I think a basic install is like 500 grand. So you don't have to be Saudi Arabia and have a $2 billion cybersecurity program running in your country. You can just be a really rich a-hole who's like, "Look, I want to blackmail this world leader, celebrity, whatever it is, because I'll make my 500 grand back. Are you kidding me? I'm going to make four or five million bucks off of this by threatening to release photos of the first lady or so-and-so on media. They're just going to pay this." So a $500,000 investment to a cybersecurity company to get me access to somebody's phone or multiple people's phones unfettered it — it's an obvious sort of good in air quotes, investment if you're a criminal. I'm sure they try and screen it. But like, are you really screening it? Do you really look at the target or you just hand over the install and it's good for one or two phones? I mean, I don't really know, but there's no way to detect it in the phone. I checked at least if you're a victim, maybe if you're working at the NSA, they can take a look at it, but you can't find it. You can't defend against it. It just does what it does. And it's like, we're really just helpless. And this was a private company selling this. It's not a hacker where you pay in Bitcoin. You freaking wire them the money to Israel or whatever.

[00:53:31] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. I don't know if the Jeff Bezos hack came down to Pegasus, but certainly, you know, we know that the Saudis used Pegasus to spy on confidants of Jamal Khashoggi. And that's part of the reason they were able to track his communications and find out he was going to go to the embassy that day. That he was picked up, tortured, and dismembered. And yeah, I worry a lot about Pegasus. This is spyware for your phone. That's manufactured by this Israeli company called NSO group, and they've been selling it to the Saudis. They've sold it to the United Arab Emirates. They've used it on a lot of dissidents and journalists. Mexico uses this. We don't necessarily think of Mexico as an authoritarian government. But a few years ago, I started getting calls from people who are reading my stories about Pegasus in Mexico. And they said, "I think I've been getting those same messages that the UAE was using to spy on dissidents' phones.

[00:54:30] And all of these people started calling and they were nutritionists. They were doctors, they were consumer rights activists. And it was like, "Why would these people have nation-state level spyware on their phone?" Well, it took a couple of months, but I put them in touch with Citizen Lab, which was able to do the forensics to find out that yes, they did have Pegasus installed on their phones. And what did they have in common? They were all people who at one point or another had publicly advocated for a soda tax in Mexico where Coca-Cola and Pepsi maintained some of the largest market share there.

[00:55:03] Jordan Harbinger: A soda tax?

[00:55:06] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. If NSO says it just sells to government, well, someone in Mexico's government was clearly getting kickbacks from someone in the soda or sugar industry and was using this nation-states spyware. That's usually reserved for terrorists and pedophiles and criminals. According to NSO group, that's what their technology is used for. But here was someone using it to intimidate nutritionists from not advocating publicly for a national soda tax. So there is a lot of room for corruption and misuse of these tools. So when I went back to NSO group and I said, "Hey, looks like abusing your spyware to spy on nutritionists and doctors in Mexico. What say you?" They said, "Well, we'll investigate." And I said, "Okay, so you'll investigate. Okay. So how do you know when your spyware is abused? Do you have any way of seeing how your technology is getting used?" "No." "Okay. So how do you find out when it's being abused?" "Well, journalists let us know.". "Okay. Well, I'm one of the three journalists who's written about this thing. So basically it'll take me a year to find out that your spyware is on these nutritionists iPhones, then I'm going to do all this reporting. Then I'm going to call you and then you're going to investigate. Okay, let's say you find out that yes, they were abusing it or someone was abusing it. What do you do?" He said, "Oh, well, we'll stop selling to them." "Okay, but this is hardware, right? You sell this hardware to these government agencies. How do you get it out of their building? You can't just go rip it out, right? They're not going to let you in." "Well, yeah, but we can starve them of features and software updates." "What?"

[00:56:39] You know, it's clear that even when there is clear cases of abuse, there's no kill switch for this spyware. These customers in government agencies will just hold onto it for as long as they can. And we just see that same story play out over and over and over and over again. And that's just with NSO group, which is one of the more expensive players in this space. And one of the more sophisticated, but below them, there are hundreds of other spyware companies that are selling to countries that have even poor human rights records than the Saudis and Mexico. And there's no oversight over this market at all.

[00:57:15] Jordan Harbinger: That's insane. The idea that it's going to take years to catch up and then they're going to go, "Well, that's it. We're not sending you the update patch that has the ability to change the app icons or whatever, right? Like it still freaking works." My parents are still using older iPhones. They're like, "I don't need an update." Okay. So what? We just let them have spyware hacking hardware that maybe in eight years is unusable because it's so outdated. And then what? Another agency says, "You know what? We fixed that problem. That was terrible. We can't — we fired that guy. He's gone. We want the new stuff though. Here's a check." "Okay, fine. We believe you because we want $45 million for the new sh*t." I mean, come on, let's be realistic here. It's insane.

[00:57:58] I also know that a lot of these countries are getting hackers from overseas. You mentioned in the book that there's like shady jobs where they kind of fly you out to — I don't know. I hate to name a country and then they're innocent. Let's say Qatar. And they're like, "You're going to be doing InfoSec." "Great." "Oh, by the way, it's all against dissidence and people that we don't like, and we're probably going to throw them in prison and they're going to die." And then they're like, "You know, I'm going to head back to New York. That's going to be a no from me, dog." But a lot of people stay and take the check, right?

[00:58:27] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. And actually, you know, just to Qatar's credit, they were actually the victims of NSO group. So—

[00:58:34] Jordan Harbinger: That's why I didn't want to name them. I screwed — I picked the one like good guy country, or at least in that respect.

[00:58:40] Nicole Perlroth: They're not really the good guy.

[00:58:41] Jordan Harbinger: Okay, fair.

[00:58:42] Nicole Perlroth: We later learned that actually they were paying off FIFA officials to hold the World Cup and all this stuff. So what happened was there were these NSA analysts operators who were starting to get job offers from contractors around the Beltway who say, "Hey, we're going to pay you four times or at least double what you're getting at NSA. And we're going to give you all sorts of fun perks. Come join us." So they joined them. They say, "Okay, we're going to fly you over to our satellite office in Abu Dhabi. And you're going to be doing the exact same work you were doing at the NSA. We're going to make sure that you're spying on terrorists and you're defending the UAE from cyber threats." Okay, it doesn't sound bad and you're getting $400,000 a year.

[00:59:25] They fly over there. And at first, sure, they're tracking terrorists' cells and ISIS' cells in the Middle East. And that's pretty much aligned with what they were doing at the NSA. Well, then very quickly it became, "Hey, we think Qatar is actually funding the Muslim brotherhood. And we think they're actually buying off FIFA officials to host the World Cup." "Can you prove that?" And these NSA guys were like, "Okay, well, this doesn't sound too far field from what I was doing earlier. Okay, but I'll have to hock into Qatar systems." "Sure. Go for it." So they hack into Qatar systems and the story, one of these former NSA guys told me it was that, you know, here they are. They're getting into Qatari Royal's emails and tracking their flight itineraries and seeing who they're meeting with and all the kinds of things that you would need to do to see if they're funding the Muslim brotherhood.

[01:00:12] Well, at one point, Michelle Obama, who was then first lady, was planning a trip to Qatar to speak about what her Let Girls Learn initiative. And she's emailing personal notes to this Qatari Sheikha and they're trading emails back and forth. And then the person who's reading them is an American, former NSA hacker stationed in Abu Dhabi who's like, "What the hell am I doing here?" And thank God, he's one of the few to say, "What the hell am I doing here?" and left. But a lot of them stayed and who knows what communications they've caught in their dragnet by now. But that's the state of play now is that even former NSA hackers, who were trained up on our taxpayer dollars, are now overseas spying on Americans or whoever gets caught in their dragnet. And it's just a great visual example of just how out of control this spyware market has become the market for hackers and their capabilities that a former NSA hacker would be sitting there reading Michelle Obama's emails from some Villa outside Abu Dhabi.

[01:01:18] Jordan Harbinger: That is shocking because it just shows you that once they get it, it's sort of like mission creep, right? I'm sure they got it to track ISIS. And then we're like, "Whoa, this is pretty awesome. Why don't we use this for some other things? I mean, just to see if there's an issue. We're not going to do anything. And then it's like, "Well, now we can look at everyone." It's kind of like — you mentioned this in the book, there's signals intelligence, there's human intelligence. And then there's like the joke, the sort of parody, the love intelligence, where people are like, "Hey, I'm using this to track terrorists," but they're like, "What my ex-girlfriend is doing, right? Like what is she up to? I couldn't find her on Facebook. Let me just — oh, look at her credit score sucks. I wonder why that is. Let me just take a look at this information. Wow. She got fired from this job. She's been up to no good." You know, and you're just in — someone says, "Wait, you shouldn't be doing that, but wait a minute, what is my ex-boyfriend up to?" So there's this mission creep thing like it's not going to be a big deal. And then it's like...you're spying on people that are supposed to have secure communication. You're using this to go after a dissident to keep a regime in power that maybe doesn't like criticism. And it's horrifying because it really is...chopped up with a bone saw when it comes to this kind of thing. I don't mean to make light of that, but that's how this goes.

[01:02:34] Nicole Perlroth: Yeah. And you know, there was a story that my colleagues at the time did — I think, it was last week, although everything's starting to blur together in the pandemic — about how the Saudi guys who dismembered Jamal Khashoggi received paramilitary training in the United States. And that was a big shock, you know, that sent all these shockwaves out. Well, the same thing has been happening digitally for a long time. We've been sending our best and brightest over to Abu Dhabi and to Riyadh and we're training up their nation-state hackers under the auspices of the war on terrorism requires that our allies in the Gulf and the Middle East have the same capabilities without thinking that one day they might think, "Oh, well, we have these capabilities. And this person is saying some things on Twitter about us, that we don't like, we're going to turn these capabilities on them. And, you know, I tell that story at one point in my book of Ahmed Mansoor, who we call the million dollar dissident, because any kind of spyware on the market has been found on this guy's phone, NSO group's Pegasus, Hacking Team's tools, other European spyware companies. All of that spyware has been found on his phone.

[01:03:45] And what he said to me was when I last interviewed him before he was locked up and thrown in solitary confinement was, "You might think you're just a voting rights activist, but one day you're going to find that someone somewhere has labeled you a terrorist and they're justifying the use of all of these tools on you and your family. And you might not think of yourself as a terrorist and every other country might not think of yourself as a terrorist, but it doesn't matter. You know, at some point you're going to get locked up and thrown in solitary confinement." And so to me, people like Ahmed Mansoor, really the canary in the coal mine saying we got to pay attention to this. We got to have rules over who are training up, who we're selling these tools to. I actually think United States as you know, the government that sort of kicked off this market long ago and it's still one of the biggest sponsors of zero days and spyware technology. I actually think it's time for us to use the power of our purse to say, "We're not going to do that business with any company that sell its tools to oppressive government. And I think we need to rework our idea of what an oppressive government is. It's not just Iran and North Korea. It's the Saudis, it's the Emirates, it's the Qataris, it's the Egyptians. We should not be training their intelligence teams to do this level of cyberwar and digital espionage. We just shouldn't. And maybe it's inevitable they'll get those tools somewhere else. But, you know, we hold ourselves to a higher standard here. We're just not meeting it and particularly not in this realm.

[01:05:21] Jordan Harbinger: We saw how the shadow broker theft of all those exploits led to ransomware attacks on British hospitals, all these different types of businesses that had nothing to do with anything. They were just trying to extort money out of it. I mean, it really is kind of like proliferation once these bad actors get it. They're like, "Well, I don't care if a bunch of people in Britain die. Who gives a crap? I want four million dollars. You know, I don't care." You're not dealing with necessarily rational actors that are thinking at the sort of nation-state level. You're dealing with somebody who is the equivalent of me, but grew up in rural Ukraine or a small town in Ukraine. And they're like, "So I never have to work again?" They'll figure out the health thing. I just want to put this into play and then it gets out of hand, especially when you get multiple players involved. North Korea has been hacking cryptocurrency exchanges to get money off. I assume, so they can buy weapons and keep working on nukes and things like that. I mean, they don't have any scruples about selling weapons, chemical weapons to Syria, for example, if they can get money. They don't care at all. So having these weapons in these different hands is really horrible, but I guess that leads to sort of my final question here was what would you say is the timeline for just a massive cyberattack against the United States? Not against Sony, you know, stealing movies or whatever, Fortune 500 companies, but against our grid, our critical infrastructure. Where do you think it will come from? And when do you think it might come? I mean, you've got to have an idea, right?