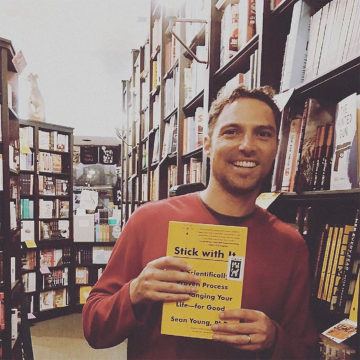

Sean Young (@SeanYoungPhD) is the Executive Director of the University of California Institute for Prediction Technology and the author of Stick with It: A Scientifically Proven Process for Changing Your Life — for Good.

What We Discuss with Sean Young:

- Archaic strategies for behavior change that almost certainly never work — even though people every day who should know better act like they never got the memo.

- The ABCs of behavior: Automatic, Burning, and Common.

- The SCIENCE model of lasting change: Stepladders, Community, Important, Easy, Neurohacks, Captivating, Engrained

- Which of these behavior change tools we can apply to each behavior type.

- How to formulate strategies to uncover, classify, and eradicate bad habits or build good habits — and make the desired changes stick.

- And much more…

- Have Alexa and want flash briefings from The Jordan Harbinger Show? Go to jordanharbinger.com/alexa and enable the skill you’ll find there!

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

Whether we have bad habits we want to eradicate or good habits we aspire to cultivate, the control required to change our behavior permanently doesn’t usually come easily or automatically. We’ve all experienced the elation of temporary change only to feel somewhat defeated when we backslide into our old behaviors. So what can we do to make these changes stick?

Sean Young, Executive Director of the University of California Institute for Prediction Technology and the author of Stick with It: A Scientifically Proven Process for Changing Your Life — for Good, joins us to share strategies for taking control over our own behavior and making the life changes we desire last for good. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

More About This Show

Is there a difference between habit change and behavior change? To someone like Sean Young — a psychologist with a PhD who specializes in digital behavior and prediction technology and authored the best-seller Stick with It: A Scientifically Proven Process for Changing Your Life — for Good, distinctions can be made depending on who you’re talking to.

“There are so many different terms for behavior!” says Sean. “People say behavior change, behavior transformation — are you talking to a wellness group? Are you talking to an HR group? Are you talking to researchers?

“I actually do separate between habit change and behavior change; on a basic level to me, the real meaning of habit is something that happens unconsciously and behavior is more broad — it’s things that we do unconsciously and consciously. [But in the context of this interview], behavior change works for me; habit change works for me. As long as we know what we’re talking about.”

So for the purpose of this episode, you’re safe using habit and behavior interchangeably.

Whatever we want to call it, it can be frustratingly difficult to switch off or on with sheer willpower. We need an actionable strategy that works.

You Can’t Be Someone Else

First, let’s look at strategies that don’t work.

Conventional wisdom once held that modeling our behavior on someone else who expressed the behavior we desired was the best course of action for behavior change. For example, someone who wanted to become healthier might try to adopt the behavior of Richard Simmons. (Never mind that someone out of shape would have a hard time keeping up with that level of energy — Simmons is a perpetual motion machine!)

“We have learned through our research that not only is that not true…but it’s pretty difficult to become a different person,” says Sean. “It doesn’t stick, and it makes people feel badly about themselves.

“Don’t change the person; change the process.”

We also know — and have known for a long time — that education alone isn’t enough to make us change our behavior. Marketing dollars spent to advertise that people shouldn’t smoke, or should get more exercise, or would be better off eating vegetables instead of cake with lunch is money wasted.

A Two-Step Process for Change

If you’re looking to get rid of bad habits or adopt good ones, Sean identifies a two-step process you can use for changing your behavior.

Step one is to identify the type of behavior you aim to change: A, B, or C.

- Automatic Behavior: Something you do without conscious awareness. Examples: biting your nails or interrupting people without even thinking about it.

- Burning Behavior: An irresistible urge or burning desire to do something. Acting on these thoughts feels almost impossible to resist, and they are nearly automatic. Examples: the need to check email immediately upon waking or a video game addiction.

- Common Behavior: Things you do repeatedly and consciously at least part of the time; these are the most common behaviors people try to change. They are not as deep-seated as automatic or burning behaviors, and they don’t cause obsession like burning behaviors. Examples: lack of motivation or making excuses for not behaving in ways that you know would be beneficial, like going to bed early, exercising more frequently, or eating healthier.

Step two is to identify the forces or tools for changing the behavior using the SCIENCE Model of Lasting Change below.

SCIENCE Model of Lasting Change

Sean devised this set of seven tools for changing behavior that uses the acronym SCIENCE for the sake of easy recall.

And yes, “engrain” is a less-common spelling of the word “ingrain,” but it’s completely valid no matter how weird it looks. We checked! So please just go with it; SCIENCI would be a pretty lame acronym.

Stepladders: Little by little, move forward using the model of steps, goals, and dreams.

- Steps: Little tasks to check off on the way to a goal.

- Goals:

- Long-term goals will take one to three months to achieve. They could take more than three months, but only if previously achieved.

- Short-term goals will take one week to one month to achieve.

- Dreams: These take more than three months to achieve and haven’t previously been achieved. Remind yourself of your dreams, but don’t keep your focus here.

Community: Be around people who are doing what you want to be doing. Social support and social competition foster change. Communities are composed of two or more people who create a social bond and facilitate lasting change (if members are engaged).

Important: To ensure that change lasts, make sure it’s really important to you. People have more success changing when it’s important to them, and if it’s important, then Stepladders and Communities can help.

Easy: Make it easy. People will do something if it’s easier for them to do it than to not do it. People want things to be easy for them to do; people enjoy things that are easy for them to do; people will keep doing things that are easy for them to do. When barriers are in front of people, they quickly stop doing something, so if you learn to remove the barriers, you’ll easily be able to keep doing things.

Neurohacks: These are psychological tricks that get someone to reset their brain by looking back on their past behavior. Our minds play tricks on us. Use these tricks to your advantage. Change begins with action. Change your actions and the mind will follow. People often decide whether to do something based on how they think of themselves. If you want to be different, start by being different, and that self-identity will make it a lot easier for you to be that person.

Captivating: People keep doing things if they’re rewarded with things they need. People will keep doing things if they feel rewarded for doing them. The reward needs to feel just as powerful as it would feel if the person were actually in a cage yearning to get out or get fed.

Engrained: This is the process the brain uses to create lasting change. Do things over and over. The brain rewards people for being repetitive and consistent. The secret to making things engrained is based on repetition: repeating behaviors, especially if they can be done every day, in the same place, and at the same time. This teaches the brain that it needs to remember the behavior to make it easier to keep doing it. Engraining causes people to favor things that are familiar.

| Automatic | Burning | Common | |

| Stepladders | T | S | |

| Community | T | P | |

| Important | T | S | |

| Easy | P | P | S |

| Neurohacks | S | S | T |

| Captivating | S | S | S |

| Engrained | P | P | S |

P = Primary

S = Secondary

T = Tertiary

Primary methods will be the most important to changing the behavior while secondary will be second and tertiary will be third. For example, for A behaviors you will use the Easy and Engrained tools first, then secondary will be Neurohacks and Captivating.

THANKS, SEAN YOUNG!

If you enjoyed this session with Sean Young, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Sean Young at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Stick with It: A Scientifically Proven Process for Changing Your Life — for Good by Sean D. Young

- Sean Young’s website

- Sean Young at Facebook

- Sean Young at Instagram

- Sean Young at Twitter

- Contagious: Why Things Catch On by Jonah Berger

- Tetris

Transcript for Sean Young - Changing Your Life for Good with SCIENCE (Episode 64)

Jordan Harbinger: [00:00:00] Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. And as always, I'm here with my producer, Jason DeFillippo. This discussion today includes insights from Sean Young. He's the Executive Director of the University of California Institute for Prediction Technology along with other accolades. He's also the author of Stick With It. He studies digital behavior and prediction technology and helps people and businesses apply this knowledge to change behaviors like sticking to new year's resolutions, and predicting what people will do in the future, especially in areas like health, medicine, politics, and business. Today, we'll discover the ABCs of behavior, these types of behavior that we do unconsciously, compulsively, or just plain bad behavior that we've rationalized when we shouldn't. We'll also explore seven forces of behavior change, each of which can be applied to a different behavior type. And last but not least, we'll learn which of the behavior change tools to apply to each behavior type so we know where attacking each specific problem with the right tool.

[00:01:02] By the end of this show, you'll have a strategy to uncover and classify habits that you don't like, or that you want to build as well as have the tools to make those changes stick. Don't forget, we have a worksheet for today's episode, which will be especially useful for this one because there's a lot of lists and things like that that you'll have want to have taken notes for, but if you're at the gym, you're driving or just walking around, you can always go grab the worksheet and it'll be done for you. And you can also solidify your understanding of the key takeaways here from Sean Young. The show is free, but the fee I ask is that you share it with friends when you find something useful, which should be every episode, and the worksheets are how we make sure of that. The link to the worksheets is in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast.

[00:01:43] Now, here's Sean Young. So behavior change. This is one of those, well have a change in behavior change, actually, is there a difference between those two things? Because I feel like we use those terms interchangeably.

Sean Young [00:01:55] Oh, man. There's so many different terms for behavior. People say behavior change, behavior transformation. It depends. Part of it is are you talking to a wellness group? Are you talking to an HR group? Are you talking to researchers? So many different ways of calling it. I actually do separate between habit change and behavior change, but yes, I mean at a basic level to me, habit change, the real meaning of habit is something that happens unconsciously, and behavior is more broad. It's things that we do unconsciously and consciously, so behavior change works for me. Habit change works for me as long as we know what we're talking about.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:02:33] I think one of the key distinctions here that maybe scares a lot of us away from habit change or behavior change is we think, well, you can't teach an old dog new tricks or I've been doing this for so long, or I've tried to change other aspects of myself and I can't do it. But in the book, you discuss that this isn't about changing the person. It's about changing the process. Can you sharpen that distinction for us as well?

Sean Young [00:03:00] I've been studying this stuff now for more than 15 years, and figured out that there are a lot of problems and reasons why people aren't able to stick with what they want to do. And there's the conventional wisdom that'll say, okay, if you want to change your behavior then become like someone else. If you want to exercise more, become like some fitness guru. Richard Simmons as the example of look how happy he is when he's exercising. If you want to exercise more, become like him. If you want to become better at business or become a social butterflies so you can sell more, become like someone else. But we've learned through our research that not only is that not true about become like another person, and really trying to change yourself, but it's pretty difficult to become a different person. It doesn't stick and it makes people feel badly about themselves. Also, if I do a lot of work, I'm a medical school professor and do a lot of work with patients and in public health.

[00:04:08] And if you start telling people that they're not having good health or not having good health behaviors because there's something wrong with them, as a person starts to feel pretty bad, starts to make them feel bad, and makes ourselves feel bad for when we're in that situation. So it turns out it's the wrong science. It's not about changing the person, you don't get behaviors to stick by changing the person and becoming someone else. It's actually, I say don't change the person, change the process. So through small tweaks in the way we do things through just little changes in our lives and there's a process for doing it, then I'll go into, we can be able to get ourselves and others to stick with things. And I think that's a really important point that's been missing for many years. And that's what's one big factor of what's been causing people to just jump to the next book, to the next motivational speaker to the next thing, and try to figure out how to be like someone else. We can't, and shouldn't try to do that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:05:05] Yeah. Moving from book to book to self-help course or video class or whatever, this stuff is ineffective. So what that signals to me is that more education, more advertising or the latest and greatest sort of habit change, trickery material that we absorbed passively isn't getting people to stick to their behavior. And it seems like we've found that a lot of these ways are just dead ends, especially for not supposed to change ourselves into a different person to do it, which is a huge relief. So how do we get people to keep doing things? And of course, later, I'll ask you how he stopped doing things, but how do we get people to keep doing things if it's not just willpower or grit?

Sean Young [00:05:46] Yeah, it's pretty unbelievable. You just said, so it's education alone is not the answer. Marketing, spending more money is not the answer, but it's unbelievable to me. We've known this stuff for years actually. I mean, good for me that it allows me to write a book and has me in a doing business in this area. But we've known for years that just educating people does not change their behavior yet. I mentioned the examples with doctors every day there's a conversation, okay, well patients aren't taking their medication and there's a belief that they're not taking it because they don't know that they're supposed to be taking it, or they don't know what the medication does for them, or even people thinking, let's educate others more about why they shouldn't smoke. And then people will quit smoking. It's not about education. It's not about pumping more money into something and advertising and marketing that there's very specific research and we know how to do this in psychology.

[00:06:51] So, what I did and stick with it, I put together that research both, the historical research over the past decades of how to get people to change their behavior as well as cutting edge work from our own group and from other friends and colleagues. And really I had narrowed it down to there's a two-step process for getting people to change their behavior. So step one is figuring out what type of behavior you're trying to change. There are three types of behaviors or what I call A, B, and C behaviors. First step is figure out which type of behavior you're trying to change A, B, or C. The second step is there are a different set of tools for changing A, B or C behavior says second.

[00:07:37] Second step is figure out which are the tools or they call forces needed for changing that type of behavior and then stick with it. There's a figure that you can look at where it will show A, B and C behaviors and then what are the tools that you can use for changing it. That's what we've done. And the research that I do, it's not just taken, like I said, from decades of research, but I've found this in my own work with patients at UCLA, with research participants in public health, in consulting that I do, and even in my own life, I've applied and found this works.

Jordan Harbinger: [00: 08:13] Perfect. Okay, well good. We know that habit change is tough because people will often, well usually even not make or keep changes even if their lives literally depend on it. You know, we see addiction and things like that. But even your own cousin, he suffers from Crohn's disease, and in the book and stick with it, you say, well, of course, what he did was he immediately changes his diet and never eats these things again and lives happily ever after. But that wasn't really the case.

Sean Young [00:08:39] So I mean, that brings up something personal and I got into this, I mean like most of us, I think especially in the public health medical field, you get into something because of some kind of personal attachment to it. And in my case, it was this related to a family member. We were in a band together. I mean, I'm a musician by training. I was in punk bands in growing up and would play with him and we played the show. I was in grad school. He came up, I was at Stanford and he came up for us to play this show and he has Crohn's disease, and he wasn't able to go back home with the rest of the bandmates after the show. And he said, you know, Sean, I'm in too much pain. And so I took him to the hospital and it turns out that his intestines had burst, which is really, really serious. He was a couple of minutes, they said away from dying. They rushed him into emergency surgery. We're able to take care of him, saved his life. He spent two or three weeks in the hospital recovering. And during that process they said, okay, look, you need to change some things around. You need to take medication, possibly for the rest of your life. You need to change the way you exercise. And Ian and my family were really close. My mom was up there, our family. And we were saying exercise, meditate, do all these things. And he said, I'm going to do it. I'm going to change my life, and start doing these things.

[00:10:17] But turns out he didn't follow through 100 percent with doing that. And it really freaked me out. I was next to him when he almost died, and here he is not following through with what needs to be done to prevent this from happening again. And so it started getting me questioning. I had been, at the time I was studying psychology, I was studying behavior change, I was working with technologies. And it got me thinking why not only he wasn't following through, but so many of us, pretty much all of us, and at least some parts in our lives don't follow through with things that we plan to do. So why is that? I was finding it with students where the students I was teaching, they would wait until the day of the test and then say, I need an extension. I didn't study for it. Or I was finding it with our band and questions like, how do we get people to come to our shows? I was working in the technology industry and finding that some friends of mine were building a software that we're getting millions of users overnight and getting people to stick with it and others weren't.

[00:11:27] And so what's the difference? What's driving engagement? So I started studying it pretty systematically, scientifically. And that's where over the past 15, more than 15 years, we've come up with some answers from doing this, and doing it in classical psychology studies in a lab, to doing it outside in the real world where we work with people who are at risk for HIV, trying to get him to get tested. We just finished a study with UCLA chronic pain patients who are on opioids, where there's an opioid crisis going on. We're applying this to suicide prevention, so many areas of public health and medicine, but then, it just applies to people's lives in every aspect of it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:12:14] So you'd mentioned A, B, C behavior or the types of behavior are A, B, and C. can you define what these are? Because I think a lot of people think, well yeah, there's addiction and then there's kind of everything else. Or are there things we think about doing? And then we do them consciously. And there's other things that we don't, what types of behavior really are there and how are they different in terms of how we attack the problem?

Sean Young [00:12:39] Yeah. I narrowed it down to three types of behavior and stick with it. So there's A, which stands for automatic behaviors. Automatic behaviors are things that we do automatically. We're not even aware of what we're doing. So we're having a conversation and if I kept interrupting you while you were talking, then I probably wouldn't even be aware that I was doing that. That would be something that was happening automatically, and that's in A behavior. Then there are B behaviors which stands for burning behaviors. Burning behaviors are things where, so unlike A behavior is where we're not aware of it, B behaviors, we're aware of it, but we feel like we can't stop ourselves from doing it. So the common one is people wake up in the morning and the first thing that they do is they'll check their phone for messages or they'll check email or if they get a ding on their phone, they'll want to check a message digital, you know what we call digital addiction is a common one. And so these are burning behaviors, and then C behaviors or common behaviors. These are the most common of all behaviors. It's why it's common behaviors. These are things that are more due to motivation. So we're aware of what we should be doing. We're aware of what we want to be doing, but other things get in the way. So I want to go for a run later on today, or I want to go read a book, whatever I want to do, but I've got work to do. I've got friends of mine come over and say, “Hey, let's go for dinner, let's grab some drinks,” things get in the way. And that stops me from being able to follow through with what I plan to do even though I'm aware of it. That's a C behavior.

[00:14:25] And the reason why it matters, so that's step one, figure out if something's an A, B, or C behavior. But this matter is these three types of behaviors because there are different tools that you can use for addressing them based upon if it's an A, B, or C behavior.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:14:41] You're listening to the Jordan Harbinger Show with our guests, Sean Young. Stick around and we'll get right back to the show after these brief messages.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:14:47] This episode is sponsored in part by Panacea skincare. Now, it's something you'd probably thought you'd hear about on this show or from a dude at all. But we have a new sponsor I want to tell you all about which is Panacea. Panacea, I believes that having great skin doesn't have to be complicated and I'm a fan of that because honestly I don't put stuff on my face usually unless I'm shaving, and I get dry skin, and I often forget to wear sunscreen and what they've got over at Panacea is a three-step essential kit for an easy skin care routine you can actually commit to. Three all-inclusive products for women and men. Cleanse, replenish, protect your skin, of course. And if you're a guy, you don't want to put any brainpower towards skin care. This stuff designed to work together. It's not a whole like routine. It's not American Psycho. Remember that, Jason, where he's like—

Jason DeFillippo: [0 :15:34] Oh yeah.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:34] He's talking about his skincare routine and you're just like, that's weird. This is just like clean, moisturize, hydrate SPF. I think I said four things, but there's three. Some of them do multiple, but the point is it doesn't smell. It's not greasy or not shiny. They all work together the products. It's easy. You can get it done. It's not a whole big to do and you don't feel like I'm in, you know, Patrick Bateman from American Psycho when you do it, and of course, we have an offer for you. Go to the panacea.com/jordan for 20 percent off.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:16:03] That's the Panacea, P-A-N-A-C-E-A.com/jordan for 20 percent off.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:16:09] This episode is also sponsored by SimpliSafe. I love this. This is like the security system of the future slash of present day because if you've looked at a security system in the past, it's something from like 1993 that somehow they've managed to raise the price but not the level of service with SimpliSafe, that is not the case at all. Easy to set up ever by the way. No drilling, no wiring, you don't need any tools. You plug in the base station, you plug your sensors wherever, doors, windows in a few minutes your whole home is protected. You don't have to have like a handyman come in and drill holes in the wall so that it can go through your landline because it's 2018, and there's no contracts. Period. Common sense. No contracts. They don't get paid unless you're happy. It's exactly the way it should be.

[00:16:52] There's no weird gotchas and they've got six monitoring centers, so if there's an earthquake, they're not like, “Oh sorry, everything's down, and it's the purge and thanks for buying our stuff.” They got backup coverage, overkill. There's power outage protection. So in a blackout, the battery backup kicks in. Like I said, purge proof, protects you for 24 hours. It's also got a cellular kit in there, so you don't need a landline like you do for every other security system. They also have 2 million clients. It sweeping up Editor's Choice Awards from all over the place. Really good at what they do. They make great products, they treat people right. Go to SimpliSafe.com/jordan to learn more.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:17:28] That's SimpliSafe. S-I-M-P-L-I-S-A-F-E.com/jordan to learn more. Thank you for listening and supporting the Jordan Harbinger Show. To learn more about our sponsors, visit jordanharbinger.com/advertisers. And don't forget to check out our Alexa Skill. Go to jordanharbinger.com/alexa, or search for Jordan Harbinger in the Alexa App and enjoy us every day with morning briefing.

[00:17:50] Now let's get back to Jordan and Sean Young.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:17:54] Okay, so A, is automatic. That's like, “Oh crap, I've been reading for an hour and I just realize I'm chewing on my thumbnail or something like this.” Right? And burning behavior is, I know I should not turn on the TV when I get home, but I really, really want it. I'll just play one round of, I don’t know, Wii tennis, I just want just one and then it's 2 o'clock in the morning, and we're like, I didn't do anything. I didn't cook dinner. I didn't talk to my wife. What's going on? That's sort of this addiction. And then can you give us a clear example of common behavior? Because I feel like that's the confusing one. Or it's like, well, wait a minute. You know, a lot of people chew their nails without thinking, “Oh wait, that's automatic.” Or a lot of people watch too much TV or play too many video games, but wait, is that burning behavior? What's common behavior as opposed to these other two?

Sean Young [00:18:42] Yeah, yeah, so, and with burning behavior, we can just in the way colloquially, we can call it addiction, but it's, but there's a clinical definition for addiction. So I use it pretty much in the way people talk about addiction, where you feel like you can't stop doing something like you mentioned, but just needed to bring up that it's different than a clinical definition of addiction. So it’s C behavior if, let's say I want to be able to exercise more, but I don't really want to exercise more that much. I'm not that motivated so that I'd rather just sit and watch Netflix shows instead of running. That's a C behavior. I know as I'm about to turn on TV or turn on a show or turn on a ball game, I'm looking at my shoes, I'm looking at my running shoes, I'm looking at my gym clothes, but saying, “No, I'm just going to stay here and grab a drink and watch TV.” That's a C behavior. We're aware of it, but we decide we're not going to do it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:19:42] Okay. So it's more of a conscious decision that we wish we could do. Maybe like go into the gym. I wish I could do more of this or less of this theoretically like maybe eating junk food, but I'm going to rationalize the behavior instead.

Sean Young: [00:19:57]Yeah, exactly. People sign up for gym membership. You know, you give the gym example, people sign up for a gym membership. They expect to be going, they’re paying for it. But then different things get in the way so that they don't end up going, it's not that they just, “Oh I completely forgot to go to the gym,”usually, can be, but usually it's,

“No, I'll go tomorrow.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:20:20] So how do we decide if something is A, automatic, B, burning, or C, common? Obviously, we can evaluate this through sort of a common sense filter, but automatic, we really have to be unaware of it. So we have, we find out because you go, “Oh, my finger's bleeding cause I've been chewing on it. Dang, I wish I could stop doing that.” But you don't have that conscious moment. All right, so we find that automatic behavior like that usually by looking at the outcome of the behavior, right? But with burning, how do we separate that? A true addiction, a true compulsion from something we just sort of feel like doing.

Sean Young: [00:20:54] Yeah, burning behavior that it is something that you feel like you've got to do. there's a small distinction. I think B and C are closer to each other than A and B. A B behavior like you said, if you find yourself just playing video games and I mean a time or that's probably closer to a B behavior where you are so distracted by it, you're so into it and you're convincing yourself, I'm just going to play one game, just one game, and then I'll be fine. That's more of a B behavior. But they're similar and oftentimes it's difficult to tell the difference and we need to, I need to talk with people or we need to kind of coach them on figuring out what the differences,

Jordan Harbinger: [00:21:39] Okay, so when we're looking at this types of behavior, this matters, right? Because in order to figure out what elements of your science acronym we applied, the behavioral change techniques we apply, we have to know whether it's burning or common because if we get it wrong, we apply the wrong elements for change. And then it fails.

Sean Young: [00:21:59] As it goes from A to B to C, you gradually need more of the tools for fixing C behaviors. In other words, you could say it's more difficult to fix a C behavior than a B behavior and A behavior. And that's probably one of the reasons why we have so many C behaviors we're trying to fix all the time. Like going to the gym and exercising and trying to work harder, read more. We have so many procrastination. So if you just kind of default to it's a C behavior, you'll be more likely to fixing in any way because there's a lot more that it takes to be able to fix a C behavior. But you're right, I think if we are just trying something and trying the tools for C behavior, it might not be as effective as if, then I'll have that with people where then they'll meet with me and I'll say, you really got to focus on making it easy, which we'll talk about in a minute, which that is important for fixing B behaviors.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:22:58] Perfect. Okay. And I'm finding it surprising that it's actually harder to change a common behavior than a burning or addictive behavior. Why do you think that is?

Sean Young: [00:23:06] Yeah, well we'll get into it. I'll get into it when I explain what the different tools are and then I think it will make more sense. But part of it is just the mind is, our brains are crazy things and we can convince ourselves of all kinds of things. We can rationalize things, and so when something's unconscious, it's almost like, A behaviors are almost animalistic. We just act without thinking. And it's a lot easier to train a dog or an animal than it is to train a person. Because we just do all kinds of mind tricks on ourselves and others

Jordan Harbinger: [00:23:42] In the book Stick With It, then you have come up with the of the acronym science to remember these seven tools are seven forces of behavior change. Take us through each one of these. Because this I thought was interesting and I love of course I'm a sucker for acronyms, especially when they actually make sense. And so these forces for habit change, not all of them apply to each type of behaviors. So to give people a sort of an overview of this. Automatic behavior isn't changed using each one of these burning behavior or addictive behavior, not change using each one of these. Common behavior, same thing. We pick and choose the forces that, the tools that we're going to use based on the type of behavior. So let's outline the tools first and then we'll talk about how to match the tool to the type of behavior.

Sean Young: [00:24:26] Yeah. So the science framework, like you said, so each one of the letters of science, it's an acronym. Each one of the letters of the word science is a different one of these seven tools or forces. It's not called science because you need to be a scientist. We need to be a doctor to know them. But just so that you remember, it's rooted in decades of scientific research on this topic. And I kind of became in writing this book, I became a sucker for acronyms like you're saying. This was actually, I've got to give the credit in creating an acronym, the idea behind it to my buddy, Jonah Berger, who wrote a book called Contagious. Jonah and I used to, we taught together at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, and he had showed me using acronyms for business people there. And then in his book Contagious, he did the same thing with something, a steps acronym, framework. And so I thought I got to have one too. And it just worked out that a science, that all the letters and science were able to be an acronym for these seven tools.

[00:25:29] So first one, that essence science stands for stepladders. Stepladder is the idea that we do things, we need to do things in small incremental steps, in order for them to be more likely to last. Oftentimes we pick things that are way too difficult, too much for us to be able to do, and then we fail at it. And there's an example, there was a guy that I ran into at the market, ran into someone at the market who was, he had been a cross country runner in high school. Then he went off and he went to the military, was trained in military intelligence, many went to Afghanistan, and served our country there and spent time there and then came back and he was telling me how he had just tried to run a marathon. And he tried to run a marathon, but he had failed. And this is a guy where we would think on this guy has everything that you'd run a marathon. He ran cross country in high school. He's smart. He went to the Language Institute and learn different languages, an army intelligence. He is dedicated and diligent. He was in the military, went through that routine process every day, but then he comes back and he can't finish a marathon. So what the hell happened? He got to mile 19 and then he just collapsed. Well, the answer is he didn't train for the marathon. Just thought I have willpower, I have the energy, I have the knowledge of how to do this. I ran cross country. I know how to do this. I can run this marathon. But he didn't go through the day to day training that we need for it.

[00:27:14] And when I started telling people that, I talked to a couple of people about this and they said, you know, that makes a lot of sense. It's pretty obvious, but even though that's obvious to us, we all do things like that in our own lives. So we all plan things that are much more difficult than we actually need to or should. So we might say, we plan new year's resolutions or summer's coming up and people say, okay, the summer is coming up. I need to look good. I'm going to start going, I'm going to exercise every day for the next four weeks so that I can hit the beach. But the past three months, six months, 12 months, maybe they exercised once a month. It's not realistic to someone exercise every day if you've been doing it once a month. And so we need to plan steps that are small steps in order for us to continue doing things.

[00:28:12] And so in this case, training for a marathon or doing things in small steps is really important. But then there's a question, how do you know, what does small step actually mean? And so in Stick With It, I created a figure called steps, goals, and dreams, which helps to quantify what a small step is by saying a dream. What I call a dream is something that takes three months or longer to achieve. So for me, running a marathon would be a dream because it's something I would have to train for a few months to be able to achieve. Goals are something that take about one month. And then a step is something that we can do today or definitely within a week. If I exercise once a month or less than that, or not very much, then maybe just getting a pair of running shoes is a first step for me. And that's what we need to focus on. That model of steps, goals, and dreams, because that will keep us on point. It will keep us on track to be able to stick with things we want to do. So that's the idea of step ladders.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:29:18] Right? So we plan these small steps towards our goal, which might be, and I think the problem that a lot of people have with this is these small steps are maybe a little bit less exciting, but they're more realistic, right? So we go, all right, I've got to go and get a pair of shoes. And then I got to do this couch to 5K running plan where I'm running for 60 seconds, walking for 60 seconds, and I got to do that for a week. And it's pretty lame because I'm only going like half a mile. But I really just want to run a marathon. But this is how you get there, right? It's that how do you eat an elephant, one bite at a time kind of thing. And you mentioned in Stick With It that big dreams can really have a reverse effect and end up demotivating you. How does that work? So if we come up with a grandiose idea, how could that demotivate us? Because you see a lot of advice online like all right, if you're going to start a business, write your big hairy audacious goal on a whiteboard and leave it in your office. You know, you hear that all the time.

Sean Young: [00:30:15] Yeah. That’s the dominant thing people say, the conventional wisdom says, I always wanted to be a rock star and I just focused, every day I thought about all the parties I would go do, and being up on stage and all the girls I would get. And that's what kept me on track to be in rock star. But that's not what the science supports. It's definitely, it's good to have that dream. It's good to have that vision. It definitely motivates us, but that's not the kind of thing that's going to allow us to stick to the day to day problems that come up because there's not always going for musician, and I know this first hand, you're not always going to have concerts where thousands of people are coming to your shows. So what do you do when you're focusing on that and you play a show and there are two people in the audience and they're checking their phones? You need to focus on the small steps in order to get you through it and keep you on track.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:15] So how small is small when we're talking about these steps? You'd mentioned these small digestible steps, small concrete goals that make us less likely to quit. What are we looking at here and why does this work? Why did these small steps work? Other than that, they're easier to accomplish.

Sean Young: [00:31:33] So in Stick With It, I get in to some of theirs, there are a bunch of reasons why it works. I mean, I get into some of the neuroscience behind it. If you think about every time you succeed at doing something or every time you feel like you succeed at something, your brain rewards you for it. Every time when you feel good, you get a rush of chemicals in your brain. And when you accomplish something, you get that rush of chemicals. Well, if we're setting our sights, if we're focusing all of our time thinking about that end goal, let's say it's I want to run a marathon. If I'm thinking about running a marathon, then I'm not going to get that rush into my brain until I run the marathon. I'm going to have to wait a really long time. But if we can get ourselves to focus on the day to day steps, and this is the tough part, but the steps literally means things that take one day or less than a week to achieve.

[00:32:28] But if we can focus on those and really ultimately after we do them reflect and say good job to ourselves or somehow reward ourselves for achieving what we did today, then we'll be able to get that rush to our brain more frequently and it will keep us on track and continue rewarding us. That's one way and there are a bunch of other ways that I talk about in Stick With It, but I think that's an important one because we need those brain chemicals to keep ourselves on track and keep doing things and so we need to divide things up into small steps so that we can do it frequently.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:33:08] Hey, we'll be right back with more from Sean Young after these extremely brief announcements.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:33:12] This episode is sponsored in part by HostGator. You have to have your own home on the web. It's that simple. With the ever shifting landscape of social media, people need to be able to find you anytime, anywhere. And I know you think, “Oh, I have a LinkedIn profile. I got social media.’ Yeah. Until something changes or your data gets jacked or they change the config and you hate it. That's why we recommend HostGator's Website Builder. You can easily create a professional looking and feature packed website and the best part there is no coding. Choose from over a hundred mobile friendly templates. Your site's going to look great on any device, smartphone, tablet, desktop. HostGator also gives you a ton of add-ons, so you can do things like increase your search engine visibility without being an expert in SEO or integrate with PayPal and allow customers to buy directly from your website.

You also get 99.9 percent guaranteed uptime. Their support team is there to help with any issues you experienced 247, 365. And HostGator's giving you guys and gals up to 62 percent off all their packages for new users. So go to hostgator.com/jordan right now to sign up. That's hostgator.com/jordan.

[00:34:16] Oh by the way, if you go to jordanharbinger.com/course and you click on Six-Minute Networking, that's our networking mini-course. So what I put in there are drills, exercises, ways to reach out to other people, create and maintain relationships. The systems I use, the little drills I use in just a few minutes a week to keep in touch with hundreds slash thousands of people and I threw that together in a little course for you all. I want everybody to have it because if I'd had it 10, 15 years ago, who knows where things would be now. This is one of the life changing game changing things that I've really implemented over the past half-decade or so that have made a huge difference. Jordanharbinger.com/course. It is free by the way. I'd just in case that wasn't clear. Jordanharbinger.com/course. And that'll be linked up in the show notes of course as well.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:35:02] Thanks for listening and supporting the Jordan Harbinger Show. Your support keeps us on the air and for a list of all the discounts from our amazing sponsors, visit jordanharbinger.com/advertisers. And if you would be as so kind, please drop us a nice rating and review in iTunes or your podcast player of choice. It helps us out and helps other people find the show. If you want some tips on how to do that, just head on over to jordanharbinger.com/subscribe. Now for the conclusion of our interview with Sean Young.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:35:30] Yeah, the stepladders process for me was a really interesting, not only in Stick With It, but looking things in my own life where I've created habit change. Stepladders have been crucial and I never really thought about the fact that it works in reinforcing consistent dopamine release. I just thought, “Oh, it's easier to put on my shoes first if that's my goal and then go out and run.” But really there is something about going, yeah, I released a bunch of dopamine into my brain, but putting on my shoes and then making it to the gym and then doing one set of one thing and now you get momentum not just physically or emotionally, but your brain is literally getting a nice feel good bath the chemicals that says you like running Jordan, keep doing it.

Sean Young: [00:36:12] Reflection is a really big part of this. A lot of what people don't do is that they don't congratulate themselves enough, and they don't realize that it's actually a pretty big task to do things that they think are pretty small. So someone will come up to me and they'll say, I want to be able to exercise is a really common one. I want to be able to exercise more. They'll tell me they don't really exercise much at all. And I'll say, okay, go out and just take a 15 minute walk today, and then text me when you're done and let me know. Just from doing that and when they come tell me and we talk about it afterwards, they don't realize how taking just that 15 minute walk as a first step is getting started with things and that they should actually congratulate themselves and reflect on it and feel good about that.

[00:37:04] Don't just muddle it up and you don't just pass it over and say, “Okay, it was 15 minute walk that was nothing.” But people really need to plan out what they're going to do, plan out the small steps and then once they do it, congratulate themselves. I mean, I'm a sucker for having task lists and just checking off, okay, I did this, I did that, I did that and that's the kind of thing where going through that process of checking something off and realizing I did this, reflect on it, let yourself feel good. And that's what helps give that rush, and keep it going.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:37:41] What about the community aspect? The accountability, the C in science?

Sean Young: [00:37:46] Yeah. So I just mentioned, you know, I'll tell someone, go take a 15 minute walk and then texts me, why do I tell them to text me? That gets into community. Community is the idea that if we get other people involved or if we're doing things with other people, we'll be more likely to stick with it. And there's part of it is sometimes social support part of its competition. It depends on the person and it depends on what you're trying to do. But general idea is that we are more motivated to do things, if other people are doing them too.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:38:22] And the easy, this one sort of self-explanatory, right? We want to keep it as simple as possible and we don't go, all right, first what you got to do is redesign your entire diet so that you don't have any gluten in. It's like, “Oh gosh, it's like cleaning the basement. I'm not doing that tomorrow.” Right?

Sean Young: [00:38:39] Yeah, and we skipped that I is for important, which is this one's pretty easy or obvious one, which is things that are important to people they'll keep doing. If I care about something, if I'm motivated to do it, then I'll keep doing it. But the interesting thing about important is that most people think if I'm not motivated to do something, if it's not important to me, I'm not going to do it. We've actually found in a bunch of studies, you can still get people to do things and we can get ourselves to do things even if they're not important to us, even if we don't care about them. E stands for easy, and easy is, it's a pretty easy concept to understand, but it's really difficult for us to implement in our lives often. So easy as the idea that things that are easy for us to do, we'll keep doing.

[00:39:29] I used to go to the gym, I used to go for runs a lot. It was exercising a lot and then I stopped going after a certain period of time. I just wasn't going as frequently. And if most people had seen or heard that that happened, they would say, “Okay, he got lazy or you know, Sean turned old and now he, now he won't exercise it. He's just tired of doing it.” But that wasn't what it is. What happened was I was working on campus at UCLA and I switched and I moved to work about a mile South of campus in a medical school, a place off campus. So now the gym that I would go to on campus was about a mile away. I had to walk, 40 minute walk just to get there. You can't really bike or get through there. And it was just a lot more difficult for me to now be able to keep exercising.

[00:40:24] So what I did, I switched. I moved to a gym that's across the street from my work and every day when I go to work, I bring a gym bag with me, a backpack, so that I have to, when I'm walking back to my car, when I'm walking back from work, I have to pass the gym and I’ve carrying my gym bag. It's almost harder for me to keep walking than it is for me to just walk into the gym with my bag. That's how you leverage easy for being able to stick with things,

Jordan Harbinger: [00:40:52] Right. So we maybe limit our choices so that we go down the path of least resistance, which is going to the gym or something like that. We create, we remove those barriers and last but not least, control the environment. We spoke with Benjamin Hardy about a willpower doesn't work and about controlling the environment and yeah, if you are already in the habit of getting dressed for work or getting dressed to work from home, but your daily wear on days where you're supposed to go to the gym is your shoes and gym clothing, because that was what was laid out right in front of you when you woke up that morning. That's an example of I think keeping things easy because instead of going, “Oh, I got to change and then go to the gym,” you go, “Well I'm already my gym clothes and I happened to be on my way to that area because I have a meeting or lunch there.” You really try to have the path of least resistance leads you towards your goals. What about N neuro hacks? It's a little vague. Can you tell us what that even means?

Sean Young: [00:41:48] Yeah. Neuro hacks is one of those where I said, I created this acronyms. I created the science framework and then I had to figure out where do I fit this idea. And so I came up with, I just called it neuro hack, so it fit. Neuro hacks is the idea that there are tricks that we can do with our brain to get ourselves to stick with things, that there are mental shortcuts that can get us to stick with things that we were never able to do before. There are ways of turning on or off a light switch in your brain so that, so that we can be able to stick with things. So an example of this, there was someone who I had who was in Stick With It, who I talked about, his name is Mauricio. He had just come out of a tough relationship and he had just gotten divorced and he's feeling down. He's a designer by trade, but he didn't really want to be working. He didn't want to be designing things. He didn't know what to do. He was just feeling depressed, focused on his ex-wife. And so he decides I'm going to, he's, he's sitting at his computer and he gets this, the flash on the screen that you get where it's okay, it's time to change your password. And he says, I'm going to use my password to change everything in my life here. And so we changed this password and he changes it to number four, give her a, forgive her, pretty simple statement, simple idea. But every day now when he'd come in and he'd have to enter in his password, now he has to think of this idea of forgive her.

[00:43:30] And when you first started doing it, it was pretty tough because it would remind him of her and he was angry. But over time he realized, I can continue type in this password. I don't have to change the password to something else and continue doing it and it's actually getting easier for me to type this forgive her. So he realized, this act of just the simple thing of typing, forgive her, was changing his brain and getting himself to actually forgive her and it worked. And he's moved on and got remarried and then he actually wanted to apply that to a different area. He was smoking and he said, “I'm going to use this to, to stop smoking.” So he changed his password to, I think it was quit smoking forever or quit smoking. And at the date of, when I had last talked to him was I think five years later, he had continued quitting smoking just overnight. That's power of neuro hacks.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:44:28] So we formed these habits because the brain wants to be efficient, right? Our brain wants to be an automatic mode, like a computer storing a username and password, for example. So the downside to some of this stuff is of course addiction. And the upside is that lasting change is really possible. And so I can see the neuro hacks working in that in that way. Do you have some exercises where people can come up with their own neuro hacks that are different than just retyping a password? Because for me, I never have to type a password in the first place. So what other types of neuro hacks are there that we can use to our advantage?

Sean Young: [00:45:04] Yeah, so some basic ones, which go along with what we've talked about already with things like step ladders is, let's say I want to learn how to play guitar by doing it every day, by setting aside, I'm going to practice for 15 minutes or an hour or whatever it is. We reflect back on our behavior and that creates a neuro hack. I wasn't someone who practiced guitar before, but now when I look back for the past week, two weeks, one month, I've been practicing guitar every day. That fundamentally resets our brains, and gets us to realize I'm capable of doing this. And in fact, I must be a guitar player, otherwise I wouldn't be doing this every day. So I have a dog named Nora Jones and she's a lab shepherd mix. And when she was a puppy, she was just kind of a nut ball, like other puppies like that. She would run around and eat things and break everything. And I'd come home and she'd run up to me and just, ah, ah, ah, run up and jump all over me.

[00:46:10] And what I did is I noticed that when she was really submissive, she had these huge, she has these huge satellite German shepherd style ears. And when she was submissive, she would sit and her ears would fall back and her eyes would kind of go down, she would look down. And so when I'd come home and she'd start jumping on me, I wouldn't just say sit or try to put her down. I would actually push your ears back. So I'd get her to sit and then push your ears back and the rest of her body would just turn into submissive mode. Like she was used to these ears controlling her and remembering that when her ears go back, that's time for her to be submissive. And that just continued to work in training her to not jump on me and not be as crazy.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:46:57] Next we have C which is captivating. And this one was interesting for me because I don't, and I'm not even sure I understand this, but somehow David George has PTSD and Tetris was able to solve the problem. How can Tetris work as a cognitive vaccine?

Sean Young: [00:47:13] There is a research study of Tetris being able to you to be used to prevent PTSD and you know, it's uncertain what actually is happening. I mean, my guess is it's a distraction. What they found is that so people who have recently experienced some kind of psychological event that could lead to PTSD, or commonly does, by having them play Tetris, it reduces likelihood of that. And that's, I think it's probably due to distraction. Again, this hasn't been studied, but my guess is, if someone is about to have some idea that's wired in their brain, like they experienced something that's really scary, that causes their brain to encode it as this is a tragic, traumatic event. But if you get distracted, then possibly the brain stops that from actually happening, and that's what Texas is maybe doing. The idea of captivating those, so captivating is the idea that we need not just any reward. So the idea of if you want people to keep doing things, you should reward them. That's pretty common sense nowadays. But people misinterpreted. It was based on research that was originally done on animals, on cats and rats, and that if you reward them, then they'll follow what you want them to do, getting out of their cage or whatever you want them to do.

[00:48:46] But people generalized it to say, okay, if you give people a reward, then that'll keep them motivated. If you give them points or badges for doing something, then they'll keep on coming to your website or using your app or doing whatever you want them to do. But the idea of captivating is it's not just any reward, not everyone cares about points or badges or they don't care about it all the time. You can't just use any reward. Just like for the initial studies that were done on animals, on cats and rats. They were given food, they were in a cage and they were allowed to come out of the cage and get some food. That's a pretty big reward. That was literally a captivating reward.

[00:49:31] And so we need, if we want to get ourselves or others to be motivated, you can't just give people any reward. It's got to be something that's what I call captivating, almost the equivalent or you know, as close as possible the equivalent of that cat or rat getting the food. The name captivating came from, we did this study on at UCLA on chronic pain patients who are on opioids and we have an online community. So we leverage the force of community that I mentioned. There was one individual on in this study who said, “Damn, this is so captivating, being in this online community. Hearing the other people like me talking about their chronic pain, their addiction risk and all these things.” He couldn't get himself up from the device, from looking at these conversations. And that's the way we want to build our technologies. That's the way we want to build programs to get people to stick with it.

[00:50:32] So just quickly, the last one, E stands for engrained and that's the idea of if you do something over and over, if you do it routinely, then it will become engrained in your brain, and it will be easy to do in. Engrained is important, this gets into your question of how do we now figure out what's important for A, B and C behaviors. Engrained by making something routine, we can turn it into a habit, we can turn it into something that's unconscious possibly. And so behaviors that are a behaviors are typically already engrained in our brain. We're not aware of it. And so we need to use that same process of trying to make something engrained to undo behaviors we want to change. If I'm not standing up straight or on walking across the street and checking email or walking across the street, that may be something I'm not even aware that I'm doing. And then we need to use that tool of engrained to engrain a different type of behavior.

[00:51:38] Another one that we need for both A and B behaviors is easy. So easy is one of those things where if we can be able to make it easy for us to do something else, we’ll no longer do it. And so then it doesn't matter if you're conscious of it or not. And the reason why we need to know the difference between A, B, and C behaviors is that, like I gave the example earlier on of interrupting, interrupting is often in A behavior, and for C behaviors, all of the seven forces, all of the seven tools are helpful for changing C behavoirs.

[00:52:19] Community is especially helpful. So that's why we use a community in many of our social interventions. But for A behaviors, something like stepladders is an important, and the reason why stepladders doesn't matter for an A behavior is if I'm interrupting you and I'm not even aware that I'm interrupting you, then I can't say, okay, I'm going to gradually interrupt you less. I'm going to just interrupt you for hanging out part of the time now. And then it just doesn't even make sense in the context of something we're not aware of what we're doing. Doing something in small steps doesn't even make sense. So that's why applying something like stepladders to A behavior, it's not going to hurt it, but it's not going to solve the problem. For A behaviors, we would use easy and engrained are the most important. But we'll also use neuro hacks and have captivating rewards for B behaviors, B are pretty similar to automatic behaviors in that we use easy and engrained and captivating rewards and neuro hacks are also a little important. And for burning behaviors, we can use stepladders community and important, but those are not the most important. The most important ones are easy and engrained. And then for common behaviors, community is the most important and neuro hacks is the least important, but stepladders important, easy, captivating and engrained are in the middle of, they're also kind of important.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:53:56] So for the worksheets for this episode, we'll have that guide to which tools to use for each type of behavior so that you can match these tools to the type of behavior that you're actually trying to eliminate. Sean, thank you so much. I love the idea that we can break our behavior down into three different types and then use the science tools, these seven tools to attack and change those types of behaviors. I think that's really powerful and I love that somebody is researching the science behind this and not just spreading wives' tales. And that's what we're all about here.

[00:54:26] Jason, I found it interesting that you could classify behavior types and I just guess I've always tried to attack the problems in the same way. Not really thinking that, yeah, unconscious behavior, compulsive behavior and thing, just plain bad behavior that I rationalize is actually different. So of course it would require a different tool to solve the problem and to make the change.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:54:46] So what are you going to change after this episode?

Jordan Harbinger: [00:54:49] Yeah, well I'll have to think about that. Slash I don't want to talk about it. I don't want to talk about it. But now, I have the tools to do it. I'm going to fill it out in the worksheet. That's what the worksheets are for. Great big thank you to Sean Young. The book title is Stick With It. And if you enjoyed this, don't forget to thank Sean on Twitter. That'll be linked up in the show notes for this episode, which can be found at jordanharbinger.com/podcast, and also tweet at me your number one takeaway here from Sean Young. I'm @jordanharbinger on both Twitter and Instagram. And don't forget, if you want to learn how to apply everything you heard from Sean Young, make sure you go grab the worksheets. Also in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast.

[00:55:27] This episode was produced and edited by Jason DeFillippo. Show notes by Robert Fogarty. Booking back office and last minute miracles by Jen Harbinger. And I'm your host, Jordan Harbinger. Throw us an iTunes review, those are always helpful and don't forget to pay that fee and share the show with those you love and even those you don't. We've got a lot more in the pipeline. We're excited to bring it to you. And in the meantime, do your best to apply what you hear on the show so you can live what you listen and we'll see you next time.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.