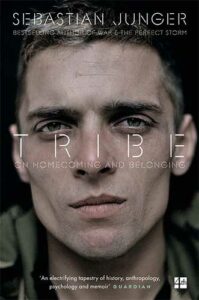

Sebastian Junger (@sebastianjunger) is a journalist, filmmaker, and bestselling author of The Perfect Storm: A True Story of Men Against the Sea. He joins us to discuss his book Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging and what he’s learned by covering war for the past 20 years. [Note: This is a previously broadcast episode from the vault that we felt deserved a fresh pass through your earholes!]

What We Discuss with Sebastian Junger:

- Why do some people get addicted to war and recall times of crisis with fondness?

- Does an affluent society free of hardship and danger deprive its citizens of an intrinsic need to be useful?

- Are war journalists armed, and do they contribute to group defense in the field?

- What happens when someone who’s been through war comes home, and why is it often so difficult for them to reintegrate into society?

- Why is there a phrase for “going native” but not “going civilized?”

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

On this episode, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging author Sebastian Junger tells us what he’s learned about human nature over 20 years of covering war as a journalist and documentary filmmaker. While you might not be surprised to learn it brings out the worst in human nature, it also facilitates the best.

Listen to this episode in its entirety to learn more about why the chance of an individual’s survival in a group goes up when they value the lives of their comrades over their own, how much a war journalist contributes to group defense in the field, why it’s often difficult for people who have been through war to reintegrate back to civilian society, why there’s a phrase for “going native” but not “going civilized,” how natives would hold ceremonies to psychologically prepare warriors to return back to the tribe, why PTSD is healthy when we’re in dangerous situations, how PTSD becomes a problem when it outlasts its usefulness, why readjustment from communal living to civilian life may be one of the major unaddressed causes of depression in people returning from war, how democracy has gotten especially messy over these past few years, and lots more. Listen, learn, and enjoy! [Note: This is a previously broadcast episode from the vault that we felt deserved a fresh pass through your earholes!]

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- TextExpander: Get 20% off your first year

- Ramp: Get $250 when you join at ramp.com/jordan

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- Progressive: Get a free online quote at progressive.com

Miss the show we did with Molly Bloom — the woman behind the most exclusive, high-stakes underground poker game in the world? Catch up here with episode 120: Molly Bloom | The One Who Makes the Rules Wins the Game!

Thanks, Sebastian Junger!

If you enjoyed this session with Sebastian Junger, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Sebastian Junger at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging by Sebastian Junger | Amazon

- The Perfect Storm: A True Story of Men Against the Sea by Sebastian Junger | Amazon

- Other Books by Sebastian Junger | Amazon

- Restrepo

- RISC (Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues)

- Sebastian Junger | Website

- Sebastian Junger | Facebook

- Sebastian Junger | Instagram

- Sebastian Junger | Twitter

710: Sebastian Junger | How War and Crisis Create Tribes

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:03] Sebastian Junger: Affluent societies don't produce communities that need the individual for anything. That great human capacity for serving the group goes unused in affluent society. We're just bothered for a while and all of a sudden that quality becomes important again, and people suddenly feel like it was the most meaningful time in their lives.

[00:00:24] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show. We decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating. We have in-depth conversations with scientists and entrepreneurs, spies and psychologists, even the occasional Fortune 500 CEO, national security advisor, undercover agent, or former jihadi. Each episode turns our guest's wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better thinker.

[00:00:52] If you're new to the show, or you want to tell your friends about the show — and of course, I always appreciate it when you do that — I suggest our episode starter packs. These are collections of our favorite episodes, organized by topic that helps new listers get a taste of everything we do here on the show — topics like persuasion, influence, disinformation and cyber warfare, China and North Korea, investing in financial crimes, and more. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started.

[00:01:18] Today, one from the vault, recorded several years ago, I'm thinking five, six, seven years ago now. We're talking with Sebastian Junger. He's a journalist, former war correspondent, and most famous for the bestselling book, The Perfect Storm, you know, the one with the waves and the boats. He's also got a handful of award-winning films under his belt, including Restrepo, Korengal, and The Last Patrol, his newest book at the time of this recording was Tribe. I may or may not have consumed all of the above in preparation for this interview.

[00:01:44] In this episode, we discussed going off to war, why humans get addicted to war, what happens when we come home, and why it's so difficult for soldiers to reintegrate into society. Even if you're not a soldier or you're not even American, you'll find the values and concepts we're talking about here in this episode, important and applicable to your life as part of society as a whole. Sebastian is a deep thinker, and I know you're going to enjoy this episode from the vault with Sebastian Junger.

[00:02:13] So Sebastian, tell us what you do in one sentence.

[00:02:17] Sebastian Junger: I'm a journalist and author and filmmaker, and I attempt to experience and understand the world so that I can explain it to others.

[00:02:25] Jordan Harbinger: Why do you say attempt to understand and explain?

[00:02:28] Sebastian Junger: Because I was raised to have a certain amount of humility about the things we all do in our lives.

[00:02:33] Jordan Harbinger: How close do you think you come to understand those topics? Because you do obviously immerse yourself really well in the topics, in what you're doing. I mean, you're in the war zone with the guys sleeping on the ground. You can't get much closer than that.

[00:02:44] Sebastian Junger: My experience with American soldiers was probably in some ways the easiest of all of my wartime experiences. I mean the really rough trips were, you know, Afghanistan in the '90s. African civil wars that I covered, those are really hard on me. And how close do I get? I think I get pretty close. I mean, I'm trained as an anthropologist and I feel like that discipline gives you a way, gives you tools for understanding human society in very, very basic terms. And those basic terms are still very much operational in what we think of as modern society. It doesn't mean humans haven't changed that much.

[00:03:17] I think I get one level of things. I mean, I get the sort of anti-anthropological deconstruction of our behavior. There's all kinds of other ways of understanding us. There's the political. You could look at the war in Afghanistan in completely political terms. I don't, but other people do as they should. It's important. You could look at it in historical terms, strategic terms, whatever. What I choose to do is understand things anthropologically so that we can understand the human behaviors that might otherwise not really make sense.

[00:03:44] Jordan Harbinger: Why were the African wars so much harder? I mean, I can venture a guess, but I am curious.

[00:03:49] Sebastian Junger: Well, I mean, if you're in a platoon of American soldiers in combat, you know that you can completely trust everyone around you. You know no one's going to shoot you in the back of the head because they're high on methamphetamine and drunk out their mind, you know? I mean, you don't have to doubt their trustworthiness, their sobriety. If you get hit, if you get hurt, there's a medic right there. You'll be better back. I mean, you're among countrymen and friends.

[00:04:11] In West Africa, the thing that was terrifying about it was the sheer level of sort of nihilism in the society and, you know, eight-year-olds with machine guns who were cranked out of their mind on drugs. And not only did they not care if you lived or died, they didn't really care if they live or die. And it's just, there's no comparison in those situations.

[00:04:27] Jordan Harbinger: We've heard of child soldiers and things like that, but very rarely do we take any kind of deep dive into that? I mean, other than watching — what was that movie? Blood Diamond, where they have a sort of a glimpse into that world. Maybe Hollywood couldn't even relay the truth because it would've just been too much for the viewer. That kind of experience must take an emotional toll that — do you still think about that stuff? Do you still wake up thinking like, "Oh crap, I'm back in Sierra Leone," or whatever?

[00:04:53] Sebastian Junger: No. I had a lot of bad dreams, a lot of psychological consequences from the civil wars that I covered in Africa, but you know, it's been a long time now. It's been 15 years. The last civil war I was in was Liberia in 2003. That was a complete and utter nightmare. And I had a lot of issues after that, but you know, that stuff goes away.

[00:05:10] Jordan Harbinger: How does it go away? What do you have to do? Or what happens?

[00:05:13] Sebastian Junger: I mean, you know, humans were animals. We're adapted to survive trauma and adapted for that matter to survive almost anything. You know, if you have a car accident, if you experience a violent assault, if you're in a war zone, whatever, like the most severe consequences come quite quickly and then they diminish over time. And eventually, it's not that you're unchanged. I mean, of course, you're changed by those experiences, but you recover psychologically and can function fine. I mean, most people recover psychologically and can function fine. So, you know, if you experience a great tragedy and you grieve, you're not functional for the first week. If your girlfriend or boyfriend dies in college, in a car accident, you're probably not functional for about a week and you're probably seriously messed up for a month. And you're definitely like, you're still grieving, you know, a year later, five years, 10 years later, you're probably not still grieving them. And yeah, it's the same thing with PTSD.

[00:06:02] Jordan Harbinger: You've got multiple films, the latest book that I read as well, Tribe, and I'm watching Restrepo and sort of these documentaries where you're embedded in Afghanistan. It was amazing to me to see these guys because there's really candid footage of guys reacting to people, getting wounded and people dying in firefights. And what they're thinking when other guys they see as better fighters than them or more athletic or guys, they look up to when those guys are killed, what it kind of does.

[00:06:27] To these guys psychologically, and they can't sleep anymore. And they don't know how to process the images and the memories. You juxtaposed that with these guys blowing off steam by dance, ambushing their teammates and blasting this like ridiculously cheesy house music and showing up in their underwear to wake somebody up. These guys are basically young guys. I'd consider kids back home in the states. Like I would expect to see these guys working at some place downtown San Jose or San Francisco hanging out, basically knowing what I knew at age 22, which was nothing. You can still see that part of them as still a kid, but they've been thrust into what seems like the worst possible part of human nature or adulthood for some of us virtually overnight.

[00:07:07] Sebastian Junger: I would say it's also in some ways the best parts of human nature. I mean, they're trained to value the lives of others as highly as they value their own lives. I mean, it's an extreme generosity and they do everything collectively. There really is an ethos of serving the group. I mean, all of these like very, very ancient, noble human ideals for very pragmatic survival reasons are abundantly in evidence in combat. And so, yeah, it's the worst environment in the world. It also oddly creates the best behavior and the best practices that is the self really devoted to the group. That's our evolutionary origins, and they reproduced pretty closely in combat in a platoon. And it's amazing to watch platoons with these all men. It's amazing to watch these young men who clearly, as humans were sort of wired to do this. Like watch them respond to that environment and react for the most part, like incredibly well. There wasn't a guy in that platoon who wouldn't have risked his life for any other person in the platoon. Those are very noble human behaviors. We actually don't see that in "better situations" like the kind of suburb I grew up in, in the '80s.

[00:08:14] Jordan Harbinger: Well, what kind of suburb did you grow up in, in the '80s? What was the situation when you were growing up that was different?

[00:08:19] Sebastian Junger: You know, I grew up in a pretty affluent, mostly white suburb of Boston. You know, there was virtually no crime. There was certainly no hardship. There was nothing that would test a young man like myself. I didn't have to somehow decide that my community needed me and that I should make sacrifices for my community because they need me. I mean, that has been the human condition for hundreds of thousands of years. And all of a sudden, you know, we live in a Western society, which is affluent enough that young people aren't really called to make sacrifices for their people, for their community. And I mean, this is the first time humans have lived like that. You know, frankly, it leaves a part of you, really that's the part of me, feeling deeply unsatisfied, deeply sort of underutilized.

[00:09:00] Jordan Harbinger: And that's how you got into war reporting, right? You wanted some kind of test of manhood, some kind of trial by fire.

[00:09:07] Sebastian Junger: Yeah, there were a number of strands to it. I mean, I went to Bosnia in the early '90s during the civil war I was in Sarajevo. Nothing particularly horrific happened, but you know, still it was an intense experience. I was in my early 30s, I worked as a climber for tree companies for years. I wanted to be a writer. Going to a war zone was a kind of practical solution to the problem of how do I break into the trade, the craft of journalism. And it was partly, a practical solution to that. And it was partly, you know, I felt like having grown up in this fairly comfortable way that I'd never really been tested and I wanted to be tested. And it is in many ways to test yourself. I mean, I could have had a kid at that age and been tested as a father. I mean, that's another way of being tested. There's all kinds of ways. The way that compelled me was putting myself in a situation where I didn't know if I would literally physically survive it. That was a war zone.

[00:09:55] Jordan Harbinger: I've been to Sarajevo as well actually. It was a life-changing experience. I wasn't there in the early '90s. That's for sure. But it was amazing to see and hear from people how horrible everything was back then and how fresh the memory was in everybody's minds. I was there in 2004, so it was already a decade later, but it was like a lot of the people that remembered it, like yesterday. One thing I thought was really strange was a lot of people were happier during the middle of this absolute horrendous crisis. And that experience was mirrored in Belgrade when people said their favorite time when they were younger was when the US was bombing Serbia.

[00:10:31] Sebastian Junger: Well, that's one of these counterintuitive things that once you start looking into it, it's just incredibly common. That hardship and danger produced positive emotional reactions to people. If you think about it, in evolutionary terms, it couldn't be otherwise. I mean, if hardship and danger produced bad human behaviors, produced selfishness, produced people, just looking out for themselves, not taking of the group, if those kinds of antisocial behaviors, the human race wouldn't survive. We evolved in a very, very dangerous environment. We are the descendants of people who responded in socially positive ways to hardship and danger, and therefore we do.

[00:11:05] So if you take a pretty affluent society and then you bomb it for a while. And of course, people die and there's tragedies and it's horrible, but people rally around the community in very selfless ways. You know, humans want to be needed. We want to be necessary. We want to be essential to our community. Affluent societies don't produce communities that need the individual for anything. That great human capacity for serving the group goes unused in affluent society. We're just bothered for a while and all of a sudden, that quality becomes important again. And people suddenly feel like it was the most meaningful time in their lives.

[00:11:40] I don't think many people would voluntarily go back to it, but they certainly look back on it with the kind of longing. And that was true in Sarajevo. It was true in London during the blitz. It was even true in Germany. I mean, I read this one study where American psychologists had talked to German psychologists after the war and the German psychologist said they couldn't understand it. The cities in Germany with the lowest morale were the cities that were not bombed by the allies and the cities that were bombed the worst bombed the hardest, like Dresden with the cities that had the highest morale. It's incredible.

[00:12:12] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, completely counterintuitive and only makes sense in the context of there being some kind of switch in the back of our brain that requires extreme adversity in order to trigger. When you're up on the mountain, when you're up in Restrepo, the operating posts, you must be constantly worried about losing someone. And I would imagine if I were there, I would've been very attached to these guys and worrying about them all the time.

[00:12:35] Sebastian Junger: When you're sort of in the moment, I wouldn't quite phrase it like that because I was also worried about myself getting hurt. What was very, very hard was being away from there. When I really worried about them was when I was safe. And that was a kind of intolerable feeling. And I'd be back in the United States. I came and went, you know, Tim and I came and went pretty regularly and I'd be back in the United States. I had enormous anxiety that something would happen to one of those guys while I was gone, not that I could have done anything about it. And I was a civilian, I'm not even a soldier. I mean, my reaction shows you the power of those feelings of concern and sort of collective outcome. We all survive together or we die together. Ironically, that mentality increases the chances of survival. That's why it exists.

[00:13:20] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Sebastian Junger. We'll be right.

[00:13:26] This episode is sponsored in part by TextExpander. TextExpander is probably one of the best productivity tools that I've ever used in my life. I use it every single day. It saves me and my entire team, literally hours or dozens of hours each month. I am really the one who responds back to all the LinkedIn messages, all the emails from you, all the DMs on Instagram, et cetera. It's not just because I don't have a life. It's because I have TextExpander, which is basically keyboard shortcuts, but on fire. And I know what you're thinking. I can copy and paste, or I already have keyboard shortcuts built into my phone. TextExpander is much more powerful than that, of course, on the desktop as well. Create customized message templates, where you can fill in a name or a date. There can be dropdowns of different message options, depending on what you want to send. TextExpander is really smart. It'll also suggest snippets based on your typing. So if you type the same thing over and over, it's like, "Hey, you might want to make this a snippet so that the current date is just FD or that the word right with a question mark after it is just the letter R type twice in a row. This is really just the tip of the iceberg. Try it out for free. Let me know how much time it saves you. A few of you wrote in and told me you implemented it at work for your entire team as well. Love to hear that.

[00:14:31] Jen Harbinger: And when you're ready to sign up, get 20 percent off your first year at textexpander.com/jordan. Go to textexpander.com/jordan to learn more about TextExpander.

[00:14:41] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Ramp. If you have company credit cards and you want more control in your spending, you've got to check out Ramp. This is such a smart idea. Ramp is a corporate card and financial software suite designed to help you save time and put money back in your pocket. With Ramp, you can create unlimited digital credit cards, each with its own set of spending limits or rules. Like, okay, Jordan's having too many tacos on the company dime make category restrictions, like no gambling sites. You can't use this card at this category of businesses. You can get instantly alerted via text if someone breaks the expense policy and no more digging and seeing what people are up to, and you can get insights on spending patterns across merchants and vendors, so you can easily see where you could be cutting costs. One thing I love is Ramp automates matching and verifying the receipts. So you text or email a photo of your receipt instead of crumpling the freaking thing up and putting it in your pocket or losing it. And it integrates with over a thousand apps like QuickBook, Zero, NetSuite, et cetera, and Ramp is really smart. It can tell if you have duplicate subscriptions and where you could be saving. So if I buy a subscription to a piece of software and someone else in my company goes to buy it, it'll be like, "Hey, you have this twice. Consider canceling one of them." So that, of course, pays for the whole dang thing. Just in duplicate subs on stuff we don't use. Plus Ramp gives 1.5 percent cash back on every purchase.

[00:15:57] Jen Harbinger: And now get $250 when you join Ramp, just go to ramp.com/jordan, ramp.com/jordan. That's R-A-M-P.com/jordan.

[00:16:08] Jordan Harbinger: If you're wondering how I managed to book all these amazing folks for the show, I've got a great networking course for you. It's a free course. It's just about how I've built my network over the years, not in the schmoozy gross way. It's about developing your networking and your connection skills and helping people develop relationships with you. It'll help you at work. It'll help you in your personal. It'll make you a better thinker. It's again free at jordanharbinger.com/course. And by the way, most of the guests on our show, they subscribe and they contribute to the course. So come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong.

[00:16:38] Now back to Sebastian Junger.

[00:16:43] I can see that. I mean, even while watching and hearing the guys talk, me and Jen, I was watching this with my girlfriend. She would say something like, "I really hope that guy is alive at the end of this." And I'm thinking, "I hope they're all alive at the end of this," because you'd find yourself just even just by virtue of watching it through this screen, you feel a little tiny percentage of that adversity when the bullets are flying in and the guys are firing back and then they're talking about, "Yeah, when we go home, we're going to visit this guy." She's like, "Oh my god if he dies, I can't handle it." And I'm thinking, it's just like, I don't want to see anything happen. And so when you're there, it's got to just be that much more intense. Although yeah, at that point, you're also worried about yourself getting something taken off. I think you're right when you're safe and you know that you're safe, it's harder to see that happen among other people. And that might explain the low morale among the German cities that were outside the war.

[00:17:30] Sebastian Junger: Well, you know, I found this amazing study from Ireland. The Irish psychologist was looking at depression rates within Irish society during what we're called the Troubles, 1969, 1970 riots in Belfast, Northern Ireland. So, what he found was that the depression rates declined in the areas that saw the most violence. They literally went down and the only area in Northern Ireland that saw depression rates rise was County Derry that saw no violence at all. You know, it's funny because he said, look, obviously we don't want to start wars in order to treat societal depression rates. But his theory was that the people in the peaceful counties knew that their brothers and sisters were suffering in other counties suffering this violence.

[00:18:14] They knew it was going on, but they couldn't do anything about it. And they weren't part of the fight, but they knew the fight was going on. That didn't make women more depressed, but it made men more depressed. They clearly felt the moral responsibility to help their brothers, but they couldn't do it. And that was intolerable. So think about veterans coming home, they know people who are still overseas fighting, and part of them is just like, "Damn, what am I doing here? Like I got to help." And that's where you get depression and you know, other related problems in veterans.

[00:18:42] Jordan Harbinger: We spoke to Dan Harris who wrote a book called 10% Happier, and he's a Nightline guy in ABC, and he had covered Afghanistan, a little bit of Iraq, I think as well. And the guy was in Restrepo as well. We're talking about the high of gun fights and they're on constant patrols where they're in firefights daily and Dan Harris had mentioned that when he was there, he didn't realize it, but when he got home, he also felt like not only did he have some sort of obligation for the people that he was around, but there's a certain high that comes with being in a war zone. It's probably part adrenaline and probably a mix of all kinds of different things from oxytocin to adrenaline and fight or flight. And he ended up self-medicating when he got back to the United States because he was hooked on different feelings that were not present in Western civilization where you can order a pizza with your phone without even making a phone call.

[00:19:31] Sebastian Junger: Yeah. I mean, I should say that there are situations, firemen and firehouses get a lot of what happens in combat and very intense bonding, the group affiliation, and of course, the adrenaline up fighting an enemy that could kill, you get a lot of that. There are other jobs, you know, logging, forest firefighting, drilling for oil, very, very dangerous work, commercial fishing. I mean, there are situations that call on a lot of those skills and a lot of that sort of human loyalty to get through it. But yeah, in American society, in general, the stakes aren't as high. When the stakes aren't as high, the sense of meaningfulness is not as high. I mean, meaningfulness goes up with consequences. And when consequences are low, the sense of meaning is quite low. And we like meaningfulness.

[00:20:13] We'll actually risk our lives in order to achieve a sense of meaningfulness in our lives. I mean, it's amazing. Clearly, that sense of meaning and purpose and belonging to a group were absolutely vital in our human evolution because we will literally risk our lives in order to have those feelings. And modern society is blessed in many ways. And you know, one of the ways in which it's blessed is that it's not life and death stakes at every moment as you're walking down the street usually. We have safety. We have a certain amount of comfort and material security, but there is a downside to that. And the downside is that there's less of a sense of meaning.

[00:20:48] Jordan Harbinger: It's not patriotic, right? I noticed that they weren't fighting for patriotism necessarily. Maybe that's what got them to join up, but they were all fighting for each other. The guys were bleeding and they're missing limbs or whatever. And they're asking, "Is this guy okay? Is that guy okay? Where's this guy? Where's this other guy? Oh, he's back there. Oh, okay." It's like, they're not even concerned as much with themselves. Is that training or is that just what happens when you spend tons of time with people or fight next to them in situations like this?

[00:21:14] Sebastian Junger: I mean, you can't train someone to value another person's life over their own. You can't train say a parent, a mother, to be more worried about their child's life in their own life. That's evolutionary wiring. Interestingly, when you have a group of people that feel that way about each other, that unit is more effective in combat than a group of people that don't feel that way about each other. And as a result, their chances of survival go up. Individually, their chances of survival go up because they're prepared to risk their life or sacrifice their life for other people that makes them tactically more effective. And then all of their chances of survival go up. And that means there's really sort of strange irony. If you're in a unit where everyone's just trying to save their own ass in combat, everybody dies. I mean, that's the irony of like trying to save yourself and only yourself as everybody dies in combat. Obviously, the human virtues of generosity and altruism and heroism and courage, I mean, we venerate those ideals, those behaviors precisely because they had enormous survival value in our evolution.

[00:22:19] Jordan Harbinger: When you're filming this, are you filming the entire time? I mean, are you filming like all day, every day?

[00:22:24] Sebastian Junger: Well, yeah, we filmed every day. We didn't produce 24 hours of footage per day. I mean, we were being a little bit selected, but yeah, yeah. My video camera never left my shoulder.

[00:22:34] Jordan Harbinger: You're not armed at all when you're up there or are you kind of like, "All right, look, I need to have something in case—"?

[00:22:38] Sebastian Junger: Anything that happens to me is going to be happening to the whole platoon. Not in any kind of individual situation ever. No, I wasn't armed. I mean, there's an ethical problem, but also you're just not contributing to the group safety unless you've been trained. It's like trying to help out the New England Patriots, like on the football pitch, right? Okay. You got one more guy on the field. You're really going to help? No, probably not. Unless you know what you're doing unless you've been trained with that team. Well, that's the same with the platoon in combat. You have to know what you're doing. You know, if someone needs you to carry a can of ammo across the outpost because they're running low on 240 ammo. Like, I mean, yeah, but the monkey could do that. I mean, that's not really participating in group defense.

[00:23:14] Jordan Harbinger: Why is it hard for guys to come back from war? Why are we developing disorders and things like that when we come home?

[00:23:19] Sebastian Junger: Well, it's hard for civilians too. And again, going back to Sarajevo as you said, and as I encountered in Sarajevo, a lot of people missed the war. A lot of people in London missed the Blitz. War and for that matter, any kind of catastrophe, an earthquake or whatever, requires people to function communally and to put their own needs sort of in the back seat to support their community first. And then, because they're part of that community, they will get taken care of second.

[00:23:45] There's something about that, that humans are wired to really respond in positive ways. And war is one of the situations that does that. Then the war ends and you go back to your old selfish, independent behaviors, and you know, it's a great Liberty, but it doesn't feel good. So when you say, why is it hard to come back from war? What you're really saying is why is it hard to go from communalism to individualism. That's actually the transition that's being made. The reason that's hard is because we're communal social species and we're wired to exist in communal groups where we're dependent on the group for our survival and the group is dependent on us to contribute.

[00:24:25] And all those things are reinforced psychologically, hormonally, culturally, socially. And then when you lose that, when you leave your platoon and wind up back in your cul-de-sac and the great American suburb, it's going against two million years of human evolution and it does not feel good.

[00:24:42] Jordan Harbinger: And this is nothing new. As you noted in Tribe, tons of white settlers in early America defected to Indian tribes. And it almost never happened the other way around. That was super interesting. I never heard about that. Obviously, it wouldn't be a popular topic in the '80s and '90s teaching American history generally and probably still isn't.

[00:25:01] What does civilization, especially Western civilization do to people and their mental and emotional health that causes us to want to run back to something different? I mean, obviously, this phenomenon's been going on for so long, this communal living. Is there any way — one, how does civilization destroy that? And two, is there any way we can get that back without destroying everything that we've built?

[00:25:21] Sebastian Junger: Yeah. It's interesting to note that we have this nice phrase to go native, right? And we all kind of know what that means and why it's appealing. And we don't say to go civilized. Like no one goes civilized, right? It's the thing we're all trying to escape. Really what you're talking about, you talk about to go native is to join a society that sort of organic tribal society, that's functioning communally. And that has enormous appeal. And I think it always has, I think it always will.

[00:25:47] Not only were settlers along the frontier, sort of absconding to pick up with the Indians, but even people who were captured in Indian raids, on frontier settlements and isolated farms, and they were captured and adopted into Indian tribes. And often when given the chance, you know, a year or two later or whatever, to be repatriated, often they refused. They didn't want to leave their adopted tribe.

[00:26:09] And that made me think of the American soldiers. I mean, a lot of the soldiers that I was with said that they didn't want to go back to the United States. They were called white Indians, actually. They're white captives of the Indians who didn't want to come back, like they were called white Indians, maybe think of the white Indians. Like, what is it about this society that makes everyone not want to return to it?

[00:26:27] You know your question basically, can we have it all? I mean, can we have the amazing benefits and blessings of this modern society? The list is endless, how fortunate we are to live in this society. I mean, your rule of law science technology, I mean, the list goes on and on. Can we have those benefits and have the kind of communalism and group identity that clearly make people feel good? I don't know. That communalism arises spontaneously during times of hardship. Can it arise by choice during times of punty? Who knows?

[00:26:58] I would like to think there's things we could do to make our society more cohesive, more organic, socially organic, but it would be a new trick for the human race. On the other hand, so does walking on the moon, and we figured it out.

[00:27:09] Jordan Harbinger: It looks like earlier civilizations like Native Americans and other cultures they'd figure this out, right? The Indians had. And I know that there's something around that word that you'd explained in your book, but you used the word Indian. So I guess, I will too. Indians and other cultures have after-war rituals and ceremonies to integrate veterans back into society. How do those work? That was really interesting. Do you know what's going on there?

[00:27:33] Sebastian Junger: Yeah. The native tribes in this country, probably most tribal societies in the world understand that the psychological stresses of combat are enormous and that the transition from a combat state of mind, to being back in your community with women and children and when there's no physical threat, that transition is difficult.

[00:27:52] And so a lot of native peoples have ceremonies, rituals that help people transition from the battlefield to the home, to the community. And often they involve a kind of dramatic retelling of your battlefield exploits and those exploits are danced and sung and drummed and recounted in many different ways. And you know, basically, you're saying to your community, "This is what I did for you. This is what a badass I am. This is how close where I came to almost getting killed but we beat the enemy. And here we are back victorious. And we lost all of our brothers and we're going to mourn them. And then we're going to go out again and take revenge on the tribe that killed our brothers."

[00:28:32] And I remember when I was at Restrepo, it wasn't my trip. Tim was on this trip and filmed it. But the footage he shot was incredible. It was after some guys were chosen. Company guys were killed in the town of whatnot and they lost a bunch of guys. And every one that was struck in the Korengal in battle company were devastated when they got the news. And Captain Kearney said basically like grieve as much as you want for like an hour. Like, "I want you to grieve and I want you to get over it, and then you're going to do your jobs. And tomorrow we're going to make the enemy feel like we feel right now. We're going to go kill them. And we're going to make them feel as bad as we feel right now."

[00:29:08] So in these ceremonies, they allow the warrior to explain what he did for the community. And they give away, you know, a proactive way to deal with feelings of grief, which is revenge, which obviously keeps wars going. But just in terms of the sort of psychological benefits to the individual. I mean, unfortunately, today, whether we go to war or not those choices are not made by 20-year-old males who grow up wanting to be soldiers. Like those choices are made by older people that hopefully are more rational, but nevertheless, those ceremonies can be incredibly therapeutic just in terms of the catharsis of telling your community openly and directly what you did for them and forcing them to hear it.

[00:29:50] I mean, that's the problem, in our society, we waged war and we actually never have to hear from the people who fight for us, what they did for us and how it made them feel. If that happened, if we could do that, liberals would feel very uncomfortable at how much many soldiers enjoy combat. I grew up in a liberal household, I know exactly what that reaction would be. Conservatives, I think, will be uncomfortable and honestly, accounts of how angry being forced to fight war can make people. And no one is comfortable with the incredible levels of grief that every war creates on all sides. Because you lose people, you lose brothers, you're never going to get him back, and you feel like you will never get over that tragedy.

[00:30:33] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Sebastian Junger. We'll be right.

[00:30:37] This episode is sponsored in part by Better Help online therapy. Life can be so overwhelming. It's important to invest in your mental health, especially during big life transitions. A friend of ours used Better Help to talk about how stressful wedding planning was and her feelings about having kids when it's more something her husband wants. She said it helped her work through the relationship issues. And if she hadn't been talking to a therapist, they might have just been useless fights. That's really good news, man. I know a lot of you think, "Oh, I don't really need therapy for that," but a lot of you have been sort of sleeping on this. Better Help is great because you can do weekly video, chat, text, phone call. You don't need to have your camera on if you don't want to. You don't have to drive anywhere if you don't want to. The convenience factor is just so huge. Especially if you think, "Oh, this isn't critical. It's not like my life is on hold because of this." You should still get therapy, but you can't really make time to do it. Now you kind of have no excuse. I always have something to talk about for an hour. I always feel better just having expressed myself as well. And our friend said it helped her stick with therapy the longest, and I can see why. Plus it's more affordable than in-person therapy. And you get matched with a therapist in under 48 hours. Jen got matched with her therapist, what? Was it 20 minutes or something like that? Less?

[00:31:43] Jen Harbinger: That's right. And our listeners get 10 percent off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan. That's better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan.

[00:31:52] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Progressive insurance. Most of you right now are probably multitasking. So while you're listening to me talk, you're probably also driving, cleaning, exercising, maybe even grocery shopping, but if you're not in some kind of moving vehicle, there's something else you could be doing right now, getting an auto quote from Progressive insurance. It's easy and you can save money by doing it right from your phone. Drivers who save by switching to Progressive save over $700 on average. And auto customers qualify for an average of seven discounts, discounts for having multiple vehicles on your policy, being a homeowner and more. So just like your favorite podcast, Progressive will be with you 24/7, 365 days a year. So you're protected no matter what. Multitask right now. Quote your car insurance at progressive.com to join the over 27 million drivers who trust Progressive.

[00:32:37] Jen Harbinger: Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. National annual average insurance savings by new customers surveyed who saved with Progressive between June 2020 and May 2021. Potential savings will vary. Discounts not available in all states and situations.

[00:32:50] Jordan Harbinger: Thank you so much for supporting the show or at least for listening to the show. Hopefully, you're also supporting the show. The advertisers, the discount codes, all those fancy-pants URLs, they're all in one place. jordanharbinger.com/deals is where you can find them. You can also search for any sponsor using the search box on the website as well. Please consider supporting those who support this show.

[00:33:10] Now for the rest of my conversation with Sebastian Junger.

[00:33:16] So what is PTSD? Speaking of grief and emotional trauma, what's going on here? Of course, it's going through the roof because there's more conflict and we are fighting on multiple fronts, but what else is happening here?

[00:33:27] Sebastian Junger: PTSD is post-traumatic stress disorder. You don't have to be a soldier to get it. You certainly don't have to be in a war zone. In the short term, it's a healthy reaction to trauma. So if you've been traumatized, your life is probably in danger and I'm speaking as an animal, the human animal is designed to survive. If it's been traumatized in some way, if it's seen dead bodies, if it's experienced a direct threat to its life, the human animal responds in pretty predictable ways.

[00:33:52] You want to be alert. You want to jump at unexpected noises because it may be that thing coming back to kill you again, you know, the tiger or whatever it was. You want to be a little bit depressed. It keeps you out of circulation until the danger has passed. You want to be quick to anger. You know, in case you are confronted, you're prepared to fight. You want to have dreams and nightmares that remind you of the threat that almost killed you, or that did kill your family or your friends.

[00:34:14] In the short term, those are all adaptive behaviors that typify a healthy response to trauma. The problem is when those behaviors get sort of ingrained permanently and you're in a perpetual trauma loop that lasts for years or your whole life. That's long-term PTSD. For most of human history, trauma was experienced collectively just because life was experienced collectively for most of human history. And the recovery from trauma was a collective process.

[00:34:45] What's very, very hard on people now is that the trauma is experienced collectively in a platoon or what have you, but the recovery happens individually because the deployment ends, everyone gets picked up and drop back down in their cul-de-sac and their suburb or wherever they live. They're not with their platoon, they're not with their wartime community. And they're trying to recover alone in isolation and not with the community that they experienced that trauma in. That is not natural, and I think that probably leads to very high rates of long-term trauma.

[00:35:15] In addition, it should be noted that only around 10 percent of the US military is regularly engaged in combat. So most of the military actually isn't even traumatized. And a much higher percentage than 10 percent experience transition disorders when they come back to this country. Because PTSD is the word that everyone knows, it gets called and even gets diagnosed as PTSD, but for a lot of these people that weren't traumatized by definition, it can't be that. But it is certainly a kind of depression that comes from the transition from a communal life to an individualized life.

[00:35:49] Peace Corps volunteers who obviously are, you know, aren't in war zones, the Peace Corps, but they are in very communal organic often even travel, or at least like agrarian communities in the developing world. And they come back to this country after two years and around 25 percent of them slip into a significant depression. It's not trauma. It is the very real difficulty of going from a communal life to an individual life. And a lot of soldiers experience that. They try to match it with something like trauma, even though maybe they weren't in combat, but maybe a rocket landed on their base one day or something, you know, they try to connect it to something because they are seriously depressed. They just don't know what it's from. And I think it's the transition to an individualized life.

[00:36:31] Jordan Harbinger: So it's almost like our Western view of PTSD as some kind of individual disorder based on trauma, looking at it like that prohibits, or basically prevents successful reintegration of veterans into our society because we look at it totally wrong. We're not even addressing the right problem. We're looking for a cause that trying to attribute that to something that wasn't necessarily there, the trauma, instead of saying, "Hey, the problem is this communal living thing," they say, "Well, all right, let's see if where the trauma is." "Well, there really wasn't that much." "Well, I guess you probably kind of don't have that. Or maybe you feel like you shouldn't have that because you weren't in combat." So now you're in limbo. All you know is you feel awful and there's no real explanation for it.

[00:37:09] Sebastian Junger: Well, yeah, there's two things. If you really truly were traumatized, and plenty of soldiers were, you'll recover more quickly and more successfully in a group situation rather than as an individual. And they've done experiments with rats. They've shown that. They've looked at child soldiers in Nepal who return to different kinds of villages. Some are socially stratified, some are not, but the ones that return to the unstratified, cohesive villages recover much, much more quickly than the others.

[00:37:35] So there's a lot of data that if you're traumatized and you remain, or you return to a communal existence, a group existence that you recover more successfully. So the first part of it is if you truly were traumatized in combat, if you're in the 10 percent that saw a lot of combat and you return home all messed up, if you return to a more communal situation, you're going to recover more successfully, more quickly.

[00:37:58] But then there's a lot of people who were never traumatized at all, but they're experiencing a very real, psychological struggle when they come home and they don't know why. Right? They're like, "Well, you know, I was a cook on a big base. I didn't fight. I never fired my weapon. Like, what the hell? Why am I so messed up here?" Well, it's possible that they're not experiencing PTSD. They're not dealing with trauma. They weren't traumatized. They're not experiencing that. What they're experiencing is the difficulties of transitioning from communal life to a solitary individualized life. That doesn't have a diagnosis. I mean, there is no diagnostic term for that, but we have the word PTSD. It gets sort of channeled through that through the paradigm of trauma, even if the trauma isn't necessarily there.

[00:38:40] Jordan Harbinger: What can I do if I'm listening to this right now, and I'm a veteran and I've come back and I realize, I feel like I'm in limbo, I feel terrible, or somebody close to me is? What recommendations can you give? I mean, I realize you're not a physician or a therapist, but what have you seen that's effective or even the beginning of effective to somebody who is affected by PTSD or whatever.

[00:39:01] Sebastian Junger: Depression, PTSD, a lot of this are not borderline so much, but there's a lot of mental health issues that are, you know, really respond to counseling, to talk therapy. And there's a lot of techniques, therapeutic techniques for helping people who have survived trauma. And again, not just soldiers, I mean, we keep thinking of PTSD is something that soldiers get. Life is traumatic. I mean, people have car accidents, they survive assaults, they have children who get cancer. I mean, life sucks for a lot of people. For everybody, eventually, life's going to suck and there's real trauma. We're really talking about all of us. I mean, we don't want to create a special case for soldiers as if they're the only people who get traumatized.

[00:39:37] So broadly speaking, like the more you are part of a vibrant connected community that needs you and you need them in order to literally survive physically. Like the more you're part of that kind of community, the better off you're going to do psychologically in all kinds of ways, not just from recovering from trauma. Women are way less likely to experience postpartum depression, for example. So that's just a helpful, good human thing, no matter what, no matter who you are.

[00:40:05] What I would say is whether you were traumatized or not, whether you're a soldier or not, if you're a human being and you've gone through a certain amount of rough stuff, as we all eventually will, the more you're part of a connected communal situation, the better off you're probably going to be. There are a lot of therapeutic techniques for helping people have experienced like real trauma.

[00:40:24] Jordan Harbinger: Thanks so much for this. I really appreciate it. And is there anything else that I haven't asked you that you want to make sure you deliver?

[00:40:30] Sebastian Junger: You know, one thing that I say to people when I talk to them, is we've lost a lot of our communal connection in our neighborhoods. You know, soldiers come back and they struggle to reintegrate into a society that's just not connected. There's nothing to reintegrate into. You know, that's all true, I think, and explains a certain amount of stuff. But in addition, one can get a sense of community from one's nation. I mean, it's different. You know, we, humans, have been used to living in groups of 300 million. We're attempting it now. You can get a certain amount of solidarity going in very large groups if you think about them in the right way.

[00:41:02] And I think one of the psychological ills of the time, that I think probably affecting soldiers quite a lot is this new idea. And you hear it in the political discourse, this new idea that somehow we're not all part of one nation. That there are groups of people who are somehow lesser or somehow exploiting other people. I remind people, which is in basic human terms, when you talk with contempt. And they are very, very powerful people who are, you know, basically running our lives and they talk with contempt about other people inside the wire, as it were. Imagine we're all soldiers like you would never talk with contempt about someone inside the wire that you may depend on for your life. When you have very powerful people in this country that do that in their political discourse, they're creating the idea that it actually isn't one unified country, that there are antithetical interests competing within the same country and only one person is going to emerge the winner.

[00:41:53] And that's a psychologically, a very, very difficult place to be. And I think it's hard on soldiers. I think it's hard on all of us. Frankly, honestly, personally, I think that kind of rhetoric is a threat to our democracy in a way that, you know, Al Qaeda and ISIS just like never will be. I mean, democracy is messy, it should be messy. That's one of the things that's very rich and amazing about it. And there's going to be a lot of conflict and disagreement and argument and differences of opinion and all that stuff. It's all great for democracy. It's great for society. It's human, but having contempt like derision and mockery and contempt for someone inside the wire, inside the tribe, is a very, very dangerous thing to do.

[00:42:30] You know, honestly, I think it can be stopped. I mean, 50 years ago, racism and public speech happened all the time. I mean, you know, soldiers came back from World War II, African-American soldiers and white American soldiers who fought side by side on the battlefield of Europe and South Pacific. And they came back to a country where in many states they could not sit side by side at a lunch counter together. Imagine what that felt like. And within the lifetime of some of those men, they saw an African-American president, like things can change and that kind of really revolting public racist speech.

[00:43:05] It's still protected under the First Amendment. It's still protected under freedom of speech as it should be, but there is such severe social sanctions against it that basically no politician, no powerful person, no matter how racist they are, really dares say that kind of thing in public. Using contempt against your fellow citizens, against your president, against your government, that also protected by free speech, of course, but it could be seen as so antithetical to American interest that is basically prohibited. Prohibited meaning that there are severe consequences for doing it. And that no one who wants to be elected in the public office does it because they'll get spanked, basically spanked at the polling booth.

[00:43:42] So I think there's a way, it's our decision. We, the people of this country, if we don't want to have our political leaders talking with that incredible disrespect about people we elect to office, about our own fellow Americans in this country, if we don't want that, we don't have to accept. And if we want to see our fellow Americans in that light, well, maybe we're not one nation. Maybe we're actually several nations and we should just get down to business and make that happen. But if we're going to stay one nation, you better start acting that way. We better start acting that way. It's within the power of we, the people, to enforce that on our political, our cultural leaders.

[00:44:17] Jordan Harbinger: Sebastian, thank you so much.

[00:44:22] Now, I've got some thoughts on this episode, but before we get into that, here's what you should check out next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:44:28] Molly Bloom: I went to LA and needed to get the first job that I could and got hired by this guy who was a pretty demanding boss. I was his personal assistant. He said, "I need you to serve drinks at my poker game." So I'm like, okay, great. And I bring my playlist and my cheese plate, and I'm thinking, you know, the players are going to be these overgrown frat boys, but Ben Affleck walks in the room and Leo DiCaprio and a politician that was very well recognized and heads of studios, heads of banks. And all of a sudden I had this light bulb moment that poker is my Trojan horse. I just need to control and have power over this game because it has this incredible hold over these people. Why do these guys with their access to anyone and anything come to this dingy basement to play this game?

[00:45:17] Jordan Harbinger: What is the most money you've seen someone lose in one night?

[00:45:20] Molly Bloom: A hundred million dollars.

[00:45:22] Jordan Harbinger: How did the mob get involved?

[00:45:24] Molly Bloom: Around Christmas, door opened and this guy that I'd never seen before pushed his way in, stuck a gun in my mouth, then he beat the hell out of me. And he kind of gave me this speech about how, if I told anyone about this or if I didn't comply, then they would take a trip to Colorado to see my family.

[00:45:40] Then the Feds got involved. And the first thing they did was they took all my money. I moved back to LA. I'd gotten a pretty decent job. 10 days later, I get a call in the middle of the night. "This is agent so-and-so from the FBI. You need to come out with your hands up." I walked into my hallway. When my eyes adjusted to the high-beam flashlights, I saw 17 FBI agents with semi-automatic weapons pointed at me.

[00:46:03] Jordan Harbinger: If you want to learn more about building rapport and generating the type of trust that Molly Bloom needed to run her multi-million-dollar operation and hear about how it all came to an end, check out episode 120 of The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:46:18] I love the ideas behind community and integration. I really do feel like we've moved well away from that even over my short lifetime. It's pretty prescient. We've definitely seen more discussion about this now than we did five, six years ago when I recorded this one. I was surprised to hear though, that there can actually be real-world mental health consequences. I guess that should not be a surprise, and yet somehow it was.

[00:46:40] It also doesn't surprise me that this is part of a problem that soldiers are facing reintegrating back into our society. A society which doesn't understand, maybe doesn't want to understand, and in fact, profoundly misunderstands these soldiers' experiences. So hopefully, if you're a soldier, you found some value here. And if you're not, you found some concepts here that you can use to improve the way you treat other people and even the way you treat yourself.

[00:47:04] Big thank you to Sebastian Junger. All things Sebastian will be in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com. Books at jordanharbinger.com/books. Please do use our website links if you buy books from anyone on the show. These links we have on that page work in other countries, they work for audiobooks. Just go ahead and use the links. And if you find any problems, please do report them to me. Transcripts are in the show notes. Videos up on YouTube. Advertisers, deals, discount codes, all of them are in one searchable place, jordanharbinger.com/deals. Please do consider supporting those who support this show. I'm at @JordanHarbinger on both Twitter and Instagram. You can also connect with me on LinkedIn.

[00:47:40] I'm teaching you how to connect with people, great people in fact, well, hopefully anyway. I'm teaching you also how to manage those relationships using systems, software, tiny habits. Dig the well before you're thirsty, folks. Build those relationships before you need them. Our Six-Minute Networking course is free. It's all for you at jordanharbinger.com/course. I don't want your credit card. I just want you to learn these skills.

[00:48:01] This show is created in association with PodcastOne. My team is Jen Harbinger, Jase Sanderson, Robert Fogarty, Millie Ocampo, Ian Baird, Josh Ballard, and Gabriel Mizrahi. Remember, we rise by lifting others. The fee for this show is that you share it with friends when you find something useful or interesting. If you know somebody who would benefit from this particular episode, somebody who's returning from war, feeling a little bit on the outs, go ahead and share this episode with them. The greatest compliment you can give us is to share the show with those you care about. In the meantime, do your best to apply what you hear on the show, so you can live what you listen, and we'll see you next time.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.