The slight, short, Soviet spy is sitting at his trial, calmly wiping his nose with a handkerchief.

It’s 1957, and he’s been arrested by the Americans for espionage. He’s being represented by an American attorney, the system is pushing for the death penalty, and he’s just found out that his Soviet bosses have disowned him.

For a Russian operative captured in the thick of the Cold War, it doesn’t get much worse than this. Even the best captured spy would be sweating bullets right about now.

“Well, the boss isn’t always right,” says the spy. “But he’s always the boss.”

His attorney shoots him a look. “Do you never worry?” he asks.

Without missing a beat, the spy responds. “Would it help?”

I’ve always loved this moment. It’s a scene from Bridge of Spies, the Spielberg movie about an American lawyer (played by Tom Hanks) fighting for a fair trial for a captured Soviet spy.

Say what you will about the rest of the movie, there’s a killer piece of wisdom here about the way we deal with life.

And the reason I know it’s a killer piece of wisdom is that it’s actually — how do I put this without dissing Spielberg? — kind of boring.

Instead of ratcheting up the drama (you know, like movies are supposed to do), the spy totally undercuts the tension of the moment with an almost Buddhist approach to life.

Tom Hanks is basically asking his client to freak out, and his client is basically saying, “Nah, I’m good. I know enough to know that I’m already in a world of pain. I don’t also need to worry about it.”

And just like that, it’s almost as if he’s not in a world of pain at all. As if by separating his emotional reaction from his circumstances, he’s found a way to not worry in the first place — a skill I know we’re all eager to master.

Can this enlightened Soviet spy teach us something about how to avoid suffering?

Help, I’m alive.

If you’ve been listening to our new show, you know that it’s been a very tumultuous and exciting adventure.

The show was born from a period of massive instability, which has taught me more about hard work, compassion, and the possibility of starting over than I ever thought I’d learn.

It’s also kicked up more challenges than I’ve had to deal with in a long time. When you’re starting a brand new company after leaving the one you co-founded and built for over 10 years, I can tell you there’s no shortage of reasons to stress, worry and catastrophize.

Every interview, every payroll deadline, every difficult negotiation is like a punch in the gut — a message from the world to your brain saying, “Time to worry. Time to freak out. Time to suffer.”

And your brain is more than happy to comply, because that’s what your brain is designed to do. In a big way, the brain’s main job is to worry. Because worrying is what motivated us to build shelter and avoid getting eaten by mountain lions.

Which is why I remembered that Bridge of Spies scene.

Would it help? I’ve been asking myself that question a lot the past couple months, hoping it would do the trick. I mean, the guy in the movie was a captured Soviet spy in the 1950s. I’m a guy launching a podcast in California in 2018. If it worked for him, it should work for me, right?

Not quite.

Because even though the question did help me separate out my reaction from my circumstances — kind of meditation 101, and something we should definitely all be doing — it didn’t ultimately change the circumstances giving rise to the suffering in the first place.

At best, it reminded me to stop worrying more than I absolutely had to. But it didn’t remove the suffering entirely. It didn’t tell me how to deal with suffering once it already arrived.

Because for most of us, suffering isn’t really a binary thing. At least it doesn’t feel that way when we’re going through it. As much as I wish it were, suffering isn’t like a light switch we can turn on and off, no matter how many self-help articles teach us “how to stop suffering,” or “ways to avoid suffering” or “the one weird reason you can’t stop suffering!”

If I’ve learned anything these past few months, it’s that suffering arises largely out of our control — quickly, insidiously, imperceptibly — and it’s up to us to invite it in, study it, learn from it, and capitalize on it, all without letting is take over completely. Which is really hard to pull off.

To do that, we need to move beyond the usual tidbits and bromides that teach us how to deal with suffering. That’s one of my biggest priorities here on the new show — giving you real practicals that are both useful and unexpected, because those are the approaches that actually generate meaningful change.

That’s what we’ll be talking about in this article. Specifically, we’ll be talking about three surprising ways to cope with suffering that I’ve learned during this period of massive change, stress and uncertainty.

Starting with a principle you might find a little strange…

Let yourself suffer.

I recently noticed something really interesting about suffering.

When pain, stress or anxiety arises in our lives, it appears first as a thought:

I’m in pain. I’m suffering.

That thought is simple, stark and usually correct. If you’re suffering, you’re going to think about it. And if you think about it, then you must be suffering.

But then — almost immediately — comes a second thought:

I want to stop being in pain. I don’t want to suffer.

Which is also a reasonable thought. Suffering isn’t pleasant, it isn’t easy, and it doesn’t seem to contribute to our wellbeing. For most of us, you can’t have the first thought without the second thought.

The third thought is instantaneous, and a perfectly natural one:

How do I do that? How do I stop suffering?

These three thoughts — I’m suffering, I don’t want to suffer, how do I stop suffering? — are the basic architecture of our distress. They’re like the foundation, walls and roof of our emotional pain house.

But if you look a little closer, you’ll find that there’s actually another thought lurking behind all of them.

It’s a thought so basic, so innocent, and so natural that most of us don’t even realize it’s there.

The thought is this:

I shouldn’t be suffering in the first place.

If the first three thoughts are the basic structure of the house, then this thought is the like the space within it — the reason the house continues to exist at all.

Because if you think about it, there are really two layers to human suffering.

There’s the suffering itself.

And then there’s the suffering about your suffering.

And that second layer of suffering usually comes from the belief that you shouldn’t be suffering in the first place.

But why shouldn’t you?

For one thing, you’re a human being. You’re literally wired to experience the world in a heightened, self-conscious, highly sensitive way. Suffering is part of the human experience.

For another, suffering arises in response to pain, and pain functions to teach us, to motivate us, to help us understand how to change. (I’ll talk more about that in just a moment, but let’s just appreciate that suffering often serves us in this way.)

When you remember that, this idea that we shouldn’t be suffering actually starts to look kind of strange.

I mean, who says we shouldn’t suffer?

What evidence do we have that we should be exempt from that experience?

Is it possible — even remotely — that we should be experiencing some pain?

And even if you don’t like those questions, is it true that you’re suffering at this moment? If so, then it doesn’t matter whether you should or shouldn’t. The fact is, you are. Which means the thought I shouldn’t be suffering doesn’t matter all that much!

If you take a hard look at what you’re going through at any given moment, I’d be willing to bet that a great deal of your suffering — maybe even most of it, in some cases all of it — is actually coming from that second layer.

The thought that says you shouldn’t be experiencing what you’re experiencing.

We could call that meta-suffering. It’s a trap I fell into big time when I left my previous company and started the new show.

For the first month or so, I felt all the stress and fear and anxiety of the experience super acutely. My professional world had been stripped away, my career was placed in jeopardy, and my identity as a broadcaster and coach — a massive part of my life — suddenly felt like an illusion.

All of that would have been more than enough suffering for me to work through, until I noticed that I was also carrying around this other burden:

The thought that I shouldn’t be dealing with any of this to begin with!

Well, why should I? I thought. I co-founded that company. I helped build it up. I developed a great show with an amazing audience. I don’t want to deal with any of this! So why do I have to?

And that’s when it hit me.

I wasn’t just suffering because of my professional circumstances. I was suffering because I was convinced that I shouldn’t have to.

The second I separated those two thoughts, I could feel the shift take place inside of me.

The stress and worry and anxiety didn’t go away entirely (honestly, I would have been suspicious if they had). But they simmered down and reduced dramatically — all because they weren’t amplified by that second layer of suffering that I had imposed on top of them.

As it happens, someone way smarter than me put it this way back in 1917:

“You can hold yourself back from the sufferings of the world, that is something you are free to do and it accords with your nature,” he wrote, “but perhaps this very holding back is the one suffering you could avoid.”

In other words?

You’re totally free to avoid pain. That’s a normal thing for a human being to do.

But maybe trying so hard to avoid that pain is actually the one form of pain you don’t have to experience in the first place.

When Franz Kafka wrote that aphorism, he was staying with his sister in Germany, recuperating from tuberculosis. So this was a guy who really understood how suffering works — how it arises, how we create it, and how much of it we actually control.

So as you move through life, and you find that pain arising, take a moment to unpack the bundle of thoughts behind that pain.

Notice how this strange conflict — I’m suffering; I shouldn’t be suffering — is actually helping to create a lot of your suffering in the first place.

I’m not telling you not to suffer. That’s not something anyone can do. You either will suffer or you won’t, depending on your circumstances and approach.

But I am telling you that you can drop this one belief that’s contributing to your suffering — this belief that says, I’m above suffering, I’m exempt from suffering, I’m suffering right now and I shouldn’t be.

Instead, drop that thought, and allow yourself to experience whatever pain seems to be arising. The pain might still be there, and it might still be very acute. But I’m willing to bet that it’s a lot less painful without the added pain arising from the belief that you shouldn’t be experiencing this pain at all.

It seems counterintuitive. How can I avoid suffering by allowing myself to suffer? But it’s actually one of the most powerful ways to reduce suffering, by consciously avoiding that unnecessary meta-suffering under our control.

That’s how we can turn the brain’s peculiar wiring against itself to alleviate the layers of suffering it’s so good at creating.

Suffer at the right time.

Another interesting feature of the brain — one of its most powerful, and one of its most destructive — is that it can contemplate the past, present and future, often simultaneously.

Just a few minutes ago, I reflected on an interview I did with a guest last week, stressed about the laundry list of tasks I have in front of me, and worried about the advertising I have to secure next quarter — all within a matter of microseconds.

That ability to relive things that have already happened and imagine things that haven’t happened yet is a form of mental time-travel.

It’s an incredible faculty that allows us to learn from our mistakes in the past and anticipate challenges in the future, so that we can adapt, plan, and survive.

Unfortunately, it’s also a really great way to suffer over things that haven’t even happened yet. And that’s where it gets us into trouble.

Because when we can experience a source of pain before it even happens, then we suffer in advance — and then we suffer again, when the source of that pain actually shows up.

For many of us, that anticipated suffering is even more acute than the actual suffering when it arrives. That’s how powerful our forward-thinking brains are.

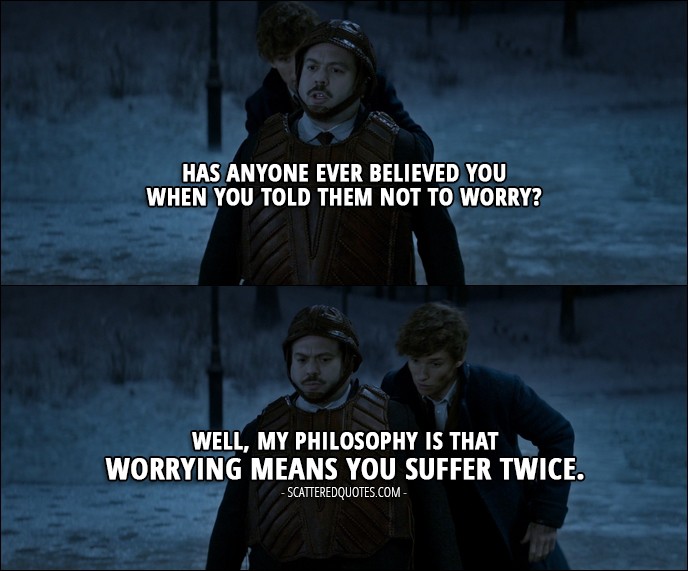

There’s a character in the movie Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them who captures this perfectly.

“My philosophy,” says Newton Scamander (magician names FTW), “is that worrying means you suffer twice.”

I know, I know. I’ve got a thing for cheeky characters with quippy one-liners about suffering.

(On a side note, can the Soviet spy from Bridge of Spies and Newt from Fantastic Beasts start a therapy practice? ‘Cuz I’d totally sign up for that.)

I should mention that J.K. Rowling is not the first person to capture this idea. You can find it in Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, for example, where one of his characters put it this way:

“If good things are coming, they will be a pleasant surprise,” said the seer. “If bad things are, and you know in advance, you will suffer greatly before they even occur.”

And the concept goes back thousands of years before that, to the earliest spiritual teachings.

All of which contain an amazing insight into the mechanics of suffering.

Because worrying, if you really think about it, is always anticipatory — it’s always looking forward.

We can’t worry about the past, because it’s already happened. We can obsess about it, or regret it, or feel ashamed about it. But we can’t worry about it.

We can only worry about the future, because we can only worry about things that haven’t happened yet.

That’s actually part of what makes those events so worrisome — the fact that they haven’t yet happened, but that we’re afraid they will.

Which means that when we worry, we’re really worrying about a thought — a thought about the future!

In other words, we’re not worrying about the actual thing we’re afraid will happen — the thing we think is going to bring us all this suffering — but the thought that that thing will happen.

And when that thing does happen — if it happens at all — then guess what?

We get to suffer twice.

First by worrying that it’ll happen.

And then again when it actually does happen.

And the best part is, we do all that while walking around with the thought, I don’t want to suffer!

I’m learning this firsthand as we build up our new show.

Almost every day, I find myself stressing about the dozens of tasks before me.

I worry about meeting my audience goals. I worry about hitting my ad targets. I worry about living up to the huge expectations my team and I have for our new show.

I worry about succeeding.

Or, to put it even more accurately, I worry about not succeeding.

But of course, what I’m really doing is projecting myself into the future — in my mind — and catastrophizing an outcome that hasn’t happened yet.

Then I turn that imagined suffering into a thought — a thought that feels like it exists right here and now, but is really just a mental fiction I’ve concocted — which allows me to obsess and stress about something that might not even happen.

And by doing that, I’m suffering right now, and setting myself up to suffer again in the future, if that imagined suffering turns out to be real. Which, if I’m being honest, it rarely does.

When you look at it that way, it’s kind of ridiculous, right?

I mean, this is the same human brain that discovered fission and painted Las Meninas and designed a reusable rocket.

That same brain is spinning mental fictions about things that haven’t happened yet — things that probably won’t happen, at least not the way we imagine them — and then torturing us with it.

Oh, humans. We’re pretty hilarious.

So when you notice yourself experiencing some form of suffering — big or small — ask yourself whether you’re suffering about something that is actually taking place, or about something that has yet to happen.

Oftentimes, you’ll find that your suffering is largely focused on the future.

In those cases, you’ve identified a form of suffering you’re free to give up whenever you’re ready — because until that future event actually plays out, you’re not obligated to obsess about it.

And once you see that, you’ll realize that one of the best ways to avoid suffering is to commit to only suffering at the right time.

When is the right time?

When the source of your suffering — the event, person, decision or outcome — actually arrives, and not a moment sooner.

Anything before that is just a thought in your head, and it’s a form of suffering you can easily avoid, as soon as you see it for what it is.

Remember To Kill A Mockingbird?

There’s a scene in the book where Jem, Atticus Finch’s son, destroys a woman’s flowers for insulting his dad. Scout, his younger sister, is concerned about what will happen to her brother when he goes over there to apologize. What Atticus tells her is something we all need to remind ourselves from time to time.

“It’s not time to worry yet.”

Choice words.

The time to worry, of course, is when the object of our worry actually comes to pass. Then we can worry. If we have to. But when we do, we often find that our worry is nowhere to be found — because our suffering is now in the present, and will soon be in the past.

Which brings us to our final principle…

Focus on sources over symptoms.

When the Founding Fathers sat down to do the unthinkable — defeat the biggest empire in the world and start a whole country — there was one overwhelming feeling they all shared.

That feeling wasn’t nobility or righteousness. It wasn’t passion or fear.

The feeling they all shared was pain.

For these guys — and all the women and men they represented — the tyranny and violence of colonial rule were the motivating force behind the (let’s be honest) insane decision to break away from England and form the republic.

They saw very clearly that people were suffering under British rule.They also saw that they could either live with that suffering, or they could choose to avoid it — if they were willing to address the sources of that suffering.

And that idea — that the key to dealing with suffering was to address its sources, not just cope with its symptoms — actually ended up in the Declaration of Independence.

“All experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.”

In normal language?

We all know that people would rather cling to their unhappiness than to actually fix the things that are making them unhappy.

We’ve all felt that. I’ve felt that.

Because as we all know, we humans love to complain about the things that make us miserable. But the second we think about actually doing something about them, we often realize that we’d rather protect our grievances — our suffering — than do the hard work to really address them.

And as long as that’s true, then we’re choosing — at least to some degree — to continue suffering.

This is by far my favorite epiphany I hear from our listeners.

When someone writes me saying, “I spent years being unhappy with my career, my partner, my health, my friends” — whatever particular form of suffering they were dealing with — “until I finally decided to do something about it,” I know they finally embraced this timeless principle.

This is where the rationalizations, the excuses and the self-pity stop, and honesty, commitment and decisions begin.

Which brings us to the final key to avoiding suffering at the end of the day: action.

It’s no surprise that Thomas Jefferson — the principal author of the Declaration — was also obsessed with doing something about it.

“Do you want to know who you are?” he once asked. “Don’t ask. Act! Action will delineate and define you.”

And if I’ve learned anything these past few months, it’s that who we are — for real, deep down — is the person obscured by the various forms of suffering in our lives.

If we allow ourselves the room to suffer when we have to — without beating ourselves up for suffering in the first place, suffering before we really have to, or accepting the symptoms of our suffering as unavoidable — then we dramatically reduce the pain, stress, and anxiety that are keeping us from doing the one thing we all know we really should be doing.

Changing. Acting. Becoming.