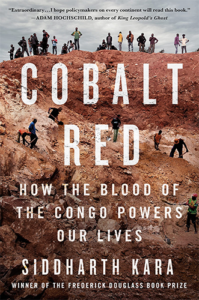

Siddharth Kara (@siddharthkara) is a British Academy Global Professor, an Associate Professor of Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery at Nottingham University, a Senior Fellow at the Harvard School of Public Health, and the author of the New York Times bestseller Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives.

What We Discuss with Siddharth Kara:

- Cobalt is an essential component of every lithium-ion rechargeable battery made today — the batteries that power our smartphones, tablets, laptops, and electric vehicles.

- About 75 percent of the world’s supply of cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, often by peasants and children in subhuman conditions who suffer and often die for their trouble.

- The environmental impact of cobalt extraction, including deforestation and pollution, that leaves behind toxic pits and wasteland unfit for sustaining life.

- The complex web of actors involved in the exploitation of Congo’s mineral resources, including smugglers, traders, and corrupt government officials.

- As consumers, what can we do to raise awareness and jolt ourselves out of the apathy that allows these atrocities to continue in our names while holding the multinational interests that perpetrate them accountable?

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

On this episode, we’re joined by Siddharth Kara, a British Academy Global Professor, an Associate Professor of Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery at Nottingham University, a Senior Fellow at the Harvard School of Public Health, and the author of the New York Times bestseller Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives. Here, Siddharth shares firsthand accounts from the Congolese people who have endured unimaginable hardships and even lost their lives in the pursuit of cobalt. He’s traveled to the toxic, militia-controlled pits where this crucial metal is mined, often finding children forced to unearth it in order to keep the global supply chains running smoothly and cheaply for the benefit of Western consumers — us. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- Nissan: Find out more at nissanusa.com or your local Nissan dealer

- Athletic Greens: Visit athleticgreens.com/jordan for a free one-year supply of vitamin D and five free travel packs with your first purchase

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- Peloton: Learn more at onepeloton.com/row

- European Wax Center: Book your free wax today at waxcenter.com

- The Missing Podcast: Listen here or wherever you find fine podcasts!

Did you hear our two-part conversation with the retired ATF agent who worked undercover for years to bust numerous criminal organizations — including a notorious motorcycle club? Catch up starting with episode 673: Ken Croke | Undercover in an Outlaw Biker Gang Part One here!

Thanks, Siddharth Kara!

If you enjoyed this session with Siddharth Kara, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Siddharth Kara at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives by Siddharth Kara | Amazon

- Other Books by Siddharth Kara | Amazon

- Siddharth Kara | The Carr Center for Human Rights, Harvard Kennedy School

- Siddharth Kara | University of Nottingham

- Siddharth Kara | The British Academy

- Siddharth Kara | Twitter

- Siddharth Kara | Instagram

- How Does a Lithium-Ion Battery Work? | Department of Energy

- Reducing Reliance on Cobalt for Lithium-Ion Batteries | Department of Energy

- The Democratic Republic of Congo | Human Rights Watch

- Cobalt Mining: The Dark Side of the Renewable Energy Transition | Earth.Org

- The Dark Side of Congo’s Cobalt Rush | The New Yorker

- Global Cobalt Reserves by Country 2022 | Statista

- Miki Mistrati | The Dark Side of the Chocolate Industry | Jordan Harbinger

- Chocolate | Skeptical Sunday | Jordan Harbinger

- Human Trafficking and Forced Labor in Global Supply Chains | International Trade Administration

- How to Identify Forced Labor in Supply Chains | SHRM

- DR Congo’s Faltering Fight Against Illegal Cobalt Mines | AFP

- Baksheesh | Wikipedia

- Nury Turkel | A Witness to China’s Uyghur Genocide | Jordan Harbinger

- Child Labour, Toxic Leaks: The Price We Could Pay for a Greener Future | The Guardian

- Uranium Flows from Congo Mines — In Burlap Bags | The Spokesman-Review

- Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | Wikipedia

- Congo Free State Rubber Regime Atrocities | ThoughtCo

- 5 of the Worst Atrocities Carried Out by the British Empire | The Independent

- The Barbaric History of Sugar in America | The New York Times

- The Abolition of Slavery In Britain | Historic UK

- To Meet Global Cobalt Demand, Companies Must Reform Mining Practices In The Congo | Forbes

- Modern Day Abolition | National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

807: Siddharth Kara | How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Special thanks to Nissan for sponsoring this episode of The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:04] Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:07] Siddharth Kara: When tech and EV companies at the top are the chain, say, "No. We buy our cobalt from ABC Industrial Company and there's no child labor involved," it's either dealing in utter falsehood or a demonstration that they are completely ignorant of the truth on the ground. Either way, there is child labor, forced labor, hazardous labor for cobalt feeding into the formal supply chain every single day.

[00:00:35] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We have in-depth conversations with scientists and entrepreneurs, spies and psychologists, even the occasional former cult member, Russian spy, music mogul, or cold case homicide investigator. And each episode turns our guest's wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better thinker.

[00:01:02] If you're new to the show or you want to tell your friends about the show, I suggest our episode starter packs as a great place to begin. These are collections of our favorite episodes organized by topics that'll help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on this — topics like persuasion and influence, disinformation and cyber warfare, crime and cults, China and North Korea, and more. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started.

[00:01:27] Don't forget, we've also got our AI search bot. You can search for any question on Feedback Friday, any interview we've ever done, or any little tidbit from any show we've ever done, jordanharbinger.com/ai is where you can find it. Let me know if you break it. Let me know if it needs to do something it's not doing. It's all a work in progress.

[00:01:44] All right, today, we're talking about cobalt. Never heard of it? Most of us haven't, but it's used in pretty much anything that uses a battery, almost certainly the device you're using to listen to my voice right now. Where is cobalt from? How is it mined? Never thought about that? Well, most of us haven't done that either until today. Today, you'll hear how something we use in enormous quantities every single day results in what sounds to me like pure human misery on the other side of the globe. You thought chocolate companies had blood on their hands just wait until you hear about cobalt.

[00:02:17] Now, here we go with Siddharth Kara.

[00:02:22] Your work is some of the most heartbreaking that I've read in a while. I read the whole book. I was like, there were times where I paused and I'm like, I got to take a deep breath here because I'm frustrated that I can't get this screw into the chassis of my remote control car that I've been working on for fun with my disposable income. And I was like thinking like, you know, some of these people who are buried alive in tunnels, they couldn't afford this literal toy that I'm playing with if they worked in this hellish situation for an entire year. And I've really had to like stop and pause just to be like, wow, I'm grateful for where I'm at. And oh my god, these people are living in hell. And we'll get to their situation in a second. But your work is documenting slavery and human trafficking. Is that accurate?

[00:03:05] Siddharth Kara: Yeah, modern-day slavery, child labor. I've been traveling around the world for more than 22 years now. 50, 60 different countries, documenting slaves and child laborers, human trafficking in just about every conceivable sector in industry and region around the world.

[00:03:20] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. We did a show on chocolate and child labor. Well, chocolate especially—

[00:03:23] Siddharth Kara: Yeah.

[00:03:24] Jordan Harbinger: —but child labor and chocolate. It's like, I guess it's Ghana, maybe Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast.

[00:03:29] Siddharth Kara: Yeah. Cote d'Ivoire.

[00:03:30] Jordan Harbinger: There's just tons of like kids, when the investigators go, they say, "Oh, it's, these are my kids." And it's like, "Well, then why are they locked in a shack in the middle of the field? And they don't look like you, and they don't speak the language that you speak," like none of it checks out.

[00:03:46] Siddharth Kara: Right.

[00:03:46] Jordan Harbinger: And then, when they're able to talk to the kids, they're like, "Yeah, I'm from Burkina Faso." And it's like, "Okay, so you just came here, you're nine. How did you get here?" Trafficked, right?

[00:03:56] Siddharth Kara: Yeah. I mean, and then you see that phenomenon across the underbelly of the global economy, the poorest people in the world, people across the global south being trafficked, recruited, exploited into serve our labor, child labor, and at the bottom ends of numerous supply chains. I mean, it would be hard for us to find a supply chain that's untouched by child labor, forced labor, another hazardous and atrocious labor exploitation.

[00:04:22] Jordan Harbinger: It's pretty disgusting when you look at it as an industry. You know, chocolate is bad, but this is even worse. We're all indirectly involved in slavery now because of especially cobalt. So you could swear off chocolate all you want, but let's talk about cobalt. What is this and why is it important?

[00:04:39] Siddharth Kara: Yeah, so people like you and I, we cannot function for 24 hours without cobalt.

[00:04:45] Jordan Harbinger: Facts.

[00:04:45] Siddharth Kara: I mean, our lives would come to a grinding halt if we did not have cobalt. And I say that because cobalt is used in the lithium-ion rechargeable batteries, almost every single lithium-ion rechargeable battery used today. So that's every smartphone, every tablet, every laptop, every e-scooter, e-bike, e anything. And then, of course, crucially electric vehicles. And about 75 percent, almost three-fourths of the world's supply of cobalt was mined in a small patch of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in utterly horrific conditions, which I know we're going to talk about but cobalt is our life force. I mean, we cannot get through a day without cobalt. So unlike, chocolate or seafood or apparel or other things that we participate in but could probably make choices, you can't make this choice. You can't forego cobalt. And so that's why it touches the lives of billions of people around the world and it's such an urgent matter to discuss.

[00:05:43] Jordan Harbinger: It's funny because I'm l reading this book or listening to the audiobook. Like I said, I'm in my garage working on this RC car and I'm surrounded by lithium polymer batteries and I'm looking at my Tesla and I'm patting myself on the back, like the pretentious ass that I am for using this vehicle that doesn't have emissions. And meanwhile, I'm surrounded by the element that these kids are pulling out of the earth with their hands. I want to go to like an earth science tangent here. How did the cobalt get there? Because Congo has so many minerals. I mean, it's got rubber and other natural resources, but it seems to have every rare earth metal that we need somewhere under the ground in this jungle or whatever. Just why are they all there?

[00:06:22] Siddharth Kara: Yeah. This is the great curse of the Congo. But let me just say one thing about your Tesla though, because you made what you felt was a good choice.

[00:06:30] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:06:30] Siddharth Kara: A responsible choice in transitioning to an electric vehicle, it's the manufacturer's responsibility to ensure that that vehicle comes to you without the appalling human rights and environmental violence that's taking place to create the battery part of that car. But we'll talk more about that. Let's get into, why is the Congo sitting on all cobalt and all these other valuable resources. And this has been the curse of the heart of Africa going back generations. It just is teeming with abundant treasures, gold, diamonds, coltan, tantalum, magnesium, zinc, copper, and of course, now cobalt. This small patch in the southeastern corner of the Congo has more cobalt in it than the rest of the planet combined.

[00:07:15] Jordan Harbinger: It's crazy.

[00:07:16] Siddharth Kara: It's all right there and it's just geographic fluke. I write in the book Cobalt Red, I spoke to a geologist, world expert geologist on cobalt to explain sort of, you know, 800 plus million years ago, there was some tectonic action that brought in seawater that leached minerals and metals into the soil. And then 600 million years ago, there was some more tectonic action that pushed everything upwards so that it's very close to the surface. And that's why this has become a human rights tragedy because you can just dig with your hands to get at the cobalt. So more than half the world's cobalt is sitting in the Congo. It's accessible by shovel. And so there's this scramble, there's this mad scramble on the ground that's devoid of any moral boundaries or any sustainability considerations. To feed cobalt up the chain into the gadgets and into the cars because there's this demand curve that looks into the future as we transition from 25 million EVs on the roads today to 300 million EVs on the roads in a decade or two. Almost all of them needing cobalt in the batters, up to 10 kilograms of refined cobalt in the battery pack. So there's a scramble going on to get cobalt out of the Congo and into the gadgets and cars.

[00:08:26] Jordan Harbinger: I used to know a guy who mined coltan in Sierra Leone, and I didn't believe him at the time. He was just a weirdo who I'd meet him in New York occasionally, and he'd have like a gold on his body and diamonds. And I'm like, "Why do you have that?" And he's like, "I wear this because if I have to escape Sierra Leon and I have it on my person." And I'm like, "Well, you're in New York. Now, you're just going to get robbed, you know, this is stupid." and he's like, "Well, I came straight from the airport and he showed me, he's got like a leg, an ankle thing with golden diamonds in it. And I was like, "What? This is stupid." And he showed me photos of what he was doing. And again, I didn't really believe that he was mining anything because it was him, a grass hut where with a hammock, a bunch of guys standing around with machine guns, and then guys with no shirts on panning for something in a muddy puddle and then another muddy area that they were working. And I said, "This is not a mine. This looks like, I mean, you know, I imagined heavy equipment," and he was just running this mine. And now I'm like, "Wow, you're kind of a bastard because you're running this operation and it's clearly not healthy for the people who are doing it." And he is like, "The whole area is full of mines run by guys like me." That's what he told me.

[00:09:33] Siddharth Kara: Exactly. And that's exactly what's happening in the Congo, except it's cobalt and there's no place else in the world to find enough cobalt to meet demand. And so, you know, stakeholders up the chain, the big tech and the EV companies, what have you believe, it's all done by excavators. And it's all done with human rights standards and sustainability principles, but you get on the ground and it's like stepping back two centuries in time where there's hundreds of thousands of people engaged in absolute brute labor with their bare hands, with pickaxes, rebar, shovels, digging in toxic trenches and pits and tunnels, and getting a dollar a day for it, maybe two dollars a day to feed cobalt up the chain to company's worth trillions.

[00:10:16] Jordan Harbinger: The companies that use this would have us think it's a bunch of Norwegian guys wearing hi-vis vests and hardhats that are directing, you know, those things you see on Discovery Channel, those giant machines and the giant dump truck. And it's like—

[00:10:28] Siddharth Kara: Right.

[00:10:28] Jordan Harbinger: —this is all done sustainably as he holds up his clipboard and it's like, "No, this is done with children who are wearing underwear, who are digging hu tunnels with, like you said, rebar and or shovels. The tunnels are crazy. Looking at these online, I was just blown away by how basic these are. How deep are the tunnels these guys are digging?

[00:10:48] Siddharth Kara: Yeah. So they're at least 10,000 to 15,000 tunnels dug by hand in the Congo. The reason artisanal miners, which is a ridiculous term—

[00:10:57] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:10:57] Siddharth Kara: —because it makes you think like they're quaint artisans doing craftsmanship work, but it's the term used by the mining industry, all this kind of obfuscation of the truth. You know, it comes down to, even to vocabulary that they use. So artisanal miners will dig these tunnels because a little bit below the surface, the grade of cobalt is a little higher. And so instead of earning maybe two dollars that day, you could earn four or five dollars that day. And that difference, of course, is an enormous amount. You know, you're talking a 100 percent increase in daily income for someone. So those tunnels are 40, 50 meters deep. The deepest I ever heard was about 60 meters. So we're talking 180 feet.

[00:11:36] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:11:37] Siddharth Kara: Straight down, dug by hand, no supports, no ventilation shafts, no rock bolts. And once they find the vein of ore that has cobalt in it, then they dig along that vein, so parallel to the surface and just enough room to crawl through and just pick at the wall. So they're crouched there, breathing in toxic particulates. Cobalt is toxic to touch and breathe. And each next little whack, the danger is the whole thing can collapse.

[00:12:04] Jordan Harbinger: I'm getting like anxiety thinking about being stuck in that tunnel.

[00:12:08] Siddharth Kara: It's a horror show. It's an absolute hellscape of human misery for a few dollars a day, and so these tunnels collapse all the time.

[00:12:16] Jordan Harbinger: I'm sure.

[00:12:16] Siddharth Kara: And everyone who's in there is just buried alive, and it's the most horrific death you could possibly imagine.

[00:12:22] Jordan Harbinger: How many people are in a tunnel at a given time? Of course, it depends on the size of the mine, but how many people are in these tunnels, and a lot of them, again, are kids? Is it like there's hundreds in one tunnel just chipping away?

[00:12:33] Siddharth Kara: Yeah, usually a few dozen. Some of the bigger tunnel complexes could have up to a hundred people down there at a time running 24-hour shifts while they just dig and they fill up a sack and pass it up, and it's pulled up to the surface using a rope. So you could have up to a hundred or more people down there. Usually, it's a few dozen though, because there's just not that much space to move around.

[00:12:55] Jordan Harbinger: How do they breathe under there? You mentioned that it's toxic, but there's no support. I assume they don't have a ventilation system as well.

[00:13:01] Siddharth Kara: No.

[00:13:01] Jordan Harbinger: I mean, if there's no support, there's no ventilation.

[00:13:03] Siddharth Kara: I came across a handful of these tunnels that had an air pump. You know, that might have been hooked up to a generator. That was like the dream scenario for some of these people to have access to an air pump. But for the most part, they're down there breathing toxic particulate matter, hour after hour, crouched in darkness. They have a little headband with a light on it to just see just in front of them. And it's very suffocating. It's very suffocating down there. And so you can't even imagine the mid to long-term health consequences of this kind of work. Again, for our cobalt, assuming of course they're not buried alive.

[00:13:41] Jordan Harbinger: I read that the OECD, which is a pretty reasonably good source, says up to 70 percent of the cobalt mining in Congo touches child labor. That alone is horrible. What percentage of cobalt is mined by machines versus hands? Do you know?

[00:13:57] Siddharth Kara: There's a lot of numbers thrown out there. No one knows the real truth, and I'll tell you why, but the rough split is probably two-thirds machine, one-third by poor peasants and children by hand.

[00:14:08] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:14:09] Siddharth Kara: Now, the reason no one really knows the exact figure and the artisanal contribution could be even more than that one-third is because, again, there's this story told outside of the Congo that there's industrial minds and then there's people digging and the two never meet, and so then they tally up industrial production divided by total tonnage that left the Congo to come up with a rough ratio. The truth of the matter is I've stepped foot inside many industrial mines in the Congo. Not all of them, because they're all guarded by guys with Kalashnikovs and machetes and so on.

[00:14:42] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:14:42] Siddharth Kara: But I managed to get into several of them, and in every single one that I did, there were artisanal mins digging inside. In some cases, thousands, 10,000 or 15,000 artisanal miners digging in these huge pits. So that production is being counted as industrial because it's inside the industrial mine, but it's not industrial at all.

[00:15:02] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:15:03] Siddharth Kara: Now, the second cross-contamination that takes place is a lot of the artisanal production. Is dug right outside the mine. So there's digging inside the mine and of course, the ore doesn't stop just where the wall of the mine is underground. So there's people digging there. And then it's just sold to an intermediary who takes it right into the mine. So, you'll never know the rough, the actual ratio, but the artisanal contribution is enormous.

[00:15:28] Jordan Harbinger: You can have a mine that's run by machines and then outside the fence there's a bunch of kids digging around looking for cobalt. And then, some shady dude who's a security guard at the mine or whatever, pays those guys a dollar a day, trucks in the sacks and says, "Throw this in with the rest of the stuff," and takes his cut.

[00:15:45] Siddharth Kara: Exactly.

[00:15:46] Jordan Harbinger: Got it.

[00:15:47] Siddharth Kara: And it's not just some shady dude, it's usually an agent of the mining company. When tech and EV companies at the top of the chain say, "No, we buy our cobalt from ABC Industrial Company and there's no child labor involved," it's either dealing in utter falsehood or a demonstration that they are completely ignorant of the truth on the ground. Either way, there is child labor, forced labor, hazardous labor for cobalt feeding into the formal supply chain every single day.

[00:16:16] Jordan Harbinger: I did an episode with this guy Miki Mistrati, about chocolate, as I mentioned earlier, episode, let me see, 754 for people who want to check it out. And he was saying that even the companies that supposedly mean well, they'll hire these third party, like, I don't know what you'd say, like an authenticator who's like, "We've followed the source all the way to the farm and we have these barcodes and these RFIDs on the sacks." And he is like, "Cool, show me how this works. What about that one?" And they were like, "Oh, they tried it and they couldn't find it." And he is like, "Oh, okay. That's weird. Try this one." And they're like, "Huh, we can't find that one either. And it seemed like the guys who worked even they didn't realize that their system of supposed third-party validation was just complete bullsh*t. And that whoever—

[00:16:57] Siddharth Kara: Yes.

[00:16:57] Jordan Harbinger: —had set this up was basically selling a certification to, let's say, Nestle or another company. And being like, "If you pay me 10,000 or whatever million dollars a year, I'll certify each sack that comes in." And they're like, "Great." And this guy's just slapping a stamp on each one and doesn't actually look at anything and nobody cares because the multinational company is satisfied and no one's going to follow up. And so he's like, "Who cares if I actually trace this back to the source?

[00:17:23] Siddharth Kara: Yeah, that's right. And that happens across the global economy from apparel to cocoa to agriculture, to seafood. I mean there's just these sort of sham systems set up that are supposedly monitoring and authenticating the supply chain. They're utter BS as you said, things like that are starting to happen in Congo where people are talking about blockchain and were following the sacks of cobalt and you get on the ground and none of it's happening.

[00:17:47] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:17:47] Siddharth Kara: Or if it is, it's just, again, total BS meant to just allay consumer concern or shareholder concern or maintain the image that these companies are good actors and they mean well, and they're saving the planet and so on.

[00:18:01] Jordan Harbinger: It must be so bizarre investigating this and going to a mine and knowing that on the earth you are standing on right now, a hundred feet or whatever below you, there are literal kids digging around for toxic rocks so that they can eat that day. You're standing on them.

[00:18:17] Siddharth Kara: What was extremely disconcerting about it, I mean, there are many things that were disconcerting, but the fact that this level of human degradation, yes, right beneath my feet, all around me is so intimately linked to our lives. You know, on the one hand, you stand in a place like the DRC where this mining is taking place, and it's like stepping into another century, another planet, another time like this can't possibly exist on the same planet as a shiny smartphone showroom in New York City. It just can't be connected. And yet it's so intimately connected and so directly connected. And so that's the pain of being in that place, knowing that this is not just some far-away offense that doesn't touch our lives. It's the basis of our daily functioning. The greater horror is that the people who live there when they walk around to follow through on this visual image you, you gave us, they're walking over the corpses of their family members who died in those tunnel collapses.

[00:19:20] And I talk in the book about a mother I met, her name is Jolie, and I met her in this neighborhood called Kasulo that is teeming with tunnels in the town of Kolwezi. And she lost her husband and son to a tunnel collapse, and she didn't want to talk about the details other than that this had happened and her life ended that she said, "After that I became a ghost." What she pointed out is the opening to that tunnel that collapsed was just a few meters from her home, and she walked over it every day and thought, "They're right there under my feet locked in their final poses of terror and horror," her son, her husband, and that was for a few dollars. So we can plug in those types of just bizarre, painful, painful horrors at the bottom of this supply chain that just, it's very painful, not just for researchers, but the people who live there. It's just the torment, the amount of torment in the Congo. It's just a place that is just an open wound in the middle of the planet.

[00:20:25] Jordan Harbinger: It really does look like what a painting of hell would look like that you see, I mean, first of all, it sounds medieval, but it looks like a medieval painting of where it's like, here are the demons tormenting the souls. And it's just kind of the same thing, right? It's you just don't have toothed creatures with wings. You have guys with AK-47s and machetes and the people are working to mine this cobalt or whatever else it is. And I know you mentioned in the book the mines also contained radioactive uranium, not that that's even the dangerous part of all this, because you're not going to live long enough to suffer the effect of that. But it's just another reason why this is so disgusting. There's no PPE, there's no hardhats.

[00:21:04] Siddharth Kara: No.

[00:21:04] Jordan Harbinger: There's no ventilators. You know, forget all that. That's not even a thing. Flashlights, if you're lucky.

[00:21:09] Siddharth Kara: The global economy has determined that these people don't count.

[00:21:13] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:21:13] Siddharth Kara: They count for nothing. So if they get sick, if they get injured, if they die, if their entire landscape around them is polluted and destroyed millions of trees, clear cut to make space for giant mines. None of that matters. That's the story that's being told by the global economy. Now, it can be denied and people can talk about their companies can talk about their zero-tolerance policies on child labor, and they adhere to human rights principles, and it makes you want to vomit.

[00:21:44] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:21:44] Siddharth Kara: You know, because none of them have gone and stepped foot there to see the truth and they don't feel that they need to because those people, those African people and the world around them don't count except for the loot, which they're trying to ransack out of the ground as quickly as possible to boost the next quarterly statement by making sure we buy the latest gadget and keep pushing the EV agenda forward, which is an important one, but it can't come at the consequence of destroying an entire population of people.

[00:22:16] Jordan Harbinger: Again, it's so much like chocolate in that all the companies that use these minerals, you've probably looked into this. I bet every single one has a policy that says we are dedicated to fair, sustainable, whatever. Some company down the line has that and they just buy it from another company that goes, "Yeah, that sounds good. Here's your blood cobalt.

[00:22:34] Siddharth Kara: Yeah. They all have these policies. They all proclaim them in their quarterly reports and their press statements and so on. The zero-tolerance policies down to the mining level, they'll always say that. We ensure human dignity of all participants in our supply chain down to the mining level. We ensure sustainability practices down to the mining level. I think, oh, okay, well, that sounds good. And then, you get into the Congo and you see it's all hot air. It's just sentences on a piece of paper. And the consequences of that hypocrisy, the consequences are utterly ruinous for some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in the world who just happened to be born in a place that was sitting on the treasure that the global economy had a voracious appetite for and that cobalt.

[00:23:21] Jordan Harbinger: And demand is going up primarily because of EVs, right? So how much cobalt is needed — tell me if you, this is just a weird question you don't know, but how much cobalt is needed in an EV versus my iPhone, for example?

[00:23:33] Siddharth Kara: Yeah, so the average smartphone, seven, eight grams of refined cobalt, maybe 10 at most if it's a big one, laptop about 30 grams of refined cobalt. Average battery pack in an EV can take up to 10 kilograms of refined cobalt. So that's 1000 times what's in the smartphone.

[00:23:53] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:23:54] Siddharth Kara: You'll say, "Okay, yeah, but smartphones is like millions are sold all e every day." Yes, and so that adds up.

[00:23:59] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:24:00] Siddharth Kara: It adds up to a lot. But if we're talking about putting two, three, 400 million EVs on the road by 2040 and many countries saying by 2035, 2040, there will be no more sales of internal combustion engines, only EVs. And you multiply that number by eight, nine, 10 kilograms of cobalt per battery pack, we're talking millions of tons of new demand on top of existing demand, and there's no place else to get that kind of cobalt, that amount except for the Congo. And that's why this, there's this scramble taking place. So every industrial mine is buying every ounce of child-mined and peasant-mined and artisanal-mined cobalt because they can't keep up with demand.

[00:24:49] Jordan Harbinger: What does cobalt actually do? I know it's in batteries. Okay, but what is the function? I assume there's a reason we can't just replace it with something else right now.

[00:24:57] Siddharth Kara: Alternate battery chemistries have been developed and I'm sure there will be future ones that are better. But the reason cobalt is so important is it allows the battery to hold maximum energy density while remaining thermally stable.

[00:25:11] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:25:11] Siddharth Kara: Now what does that mean? That means it holds more charge and won't catch on fire.

[00:25:16] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:25:16] Siddharth Kara: And the reason you want to hold more charges is because you don't want to plug in your phone three times a day and you don't want to plug in your car two times a day. It's all about holding charge. Now, the more charge you hold, the more unstable things can become thermally, and you don't want your phone and certainly, your car to catch on fire.

[00:25:31] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:25:32] Siddharth Kara: Cobalt locks down that energy, okay? So that's why it's so valuable. Now, you can horse trade, you can use a little less cobalt, and then you've got a little lower energy density, so the car won't go quite as far and your phone won't last quite as long. You can forego cobalt and then your horse trading again, energy density, thermal stability, and so on. And there are, I don't know about phones. I think all the phones are using lithium cobalt oxide batteries, which means quite a bit of cobalt. There are EVs on the road that don't have cobalt right now, but when we're talking hundreds of millions of EVs into the future, most of which are going to have cobalt, it's all Congo and it's just going to be an utter hellscape for the people living there.

[00:26:11] Jordan Harbinger: It makes sense. Again, I'm like a nerd with the RC cars and there's batteries that you get that discharge really quickly and if they get too hot, they will explode or catch on fire. So they, the high quality ones, they just get a little bit warm and they discharge really quickly and they can charge quickly. They probably have a crap load of cobalt in there.

[00:26:29] Siddharth Kara: Yeah.

[00:26:29] Jordan Harbinger: Because it's a lithium polymer that basically can just spontaneously combust if they, and if it gets exposed to air, it's a whole thing. So like they probably use a ton of this stuff. They're already kind of like a ticking time bomb if you don't treat them well.

[00:26:42] Siddharth Kara: Quite right. Yeah.

[00:26:43] Jordan Harbinger: Is there a such thing as clean cobalt? I mean, these mines obviously not, but is there a way to do it for five, 10 times the price where it just isn't horrible?

[00:26:52] Siddharth Kara: No, there's no clean cobalt from the Congo.

[00:26:54] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:26:54] Siddharth Kara: Okay. And that's three-fourths of the world's supply.

[00:26:57] Jordan Harbinger: Oh wow.

[00:26:57] Siddharth Kara: There's also cobalt mines in Australia, Canada, Morocco. If you look at the pie chart for global contribution of cobalt, as I said, it's roughly three-fourths Congo, and then, there's a lot of other countries that are two percent, three percent, two percent. So none of that cobalt, which I'm sure is mined in perfectly reasonable conditions in Australia and Canada and so on, that's not going to meet demand today, let alone into the future. So the cobalt that's coming out of the Congo, that's the human rights tragedy that has to be addressed as well as the environmental tragedy that has to be addressed.

[00:27:33] Jordan Harbinger: There are so many birth defects, there's heavy metals, rare minerals in people's blood in the Congo. I know you mentioned that in the book, the medical, so the blood work from these people is just horrific. I mean, you're looking at people that have tend to a hundred times the concentration acceptable of, what was it? Lead, lithium—

[00:27:52] Siddharth Kara: All kinds of heavy metals, yeah. So I mean, after my first trip when I was there, looking around and the air is a toxic haze. Your eyes are burning, throat is sore.

[00:28:03] Jordan Harbinger: Ugh.

[00:28:03] Siddharth Kara: And you go to little streams or ponds and there's sludge and so on, and lakes are covered. Everything has just been contaminated. And so I thought, what is this doing to people? Like even if you don't dig for cobalt, all this mining activity is still having an enormous public health impact. And I met one researcher, a toxicologist who I write about in Cobalt Red who started doing some of these tests, like getting people's urine and blood and hair and seeing what is in it. And they had 30, 40 times the maximum recommended WHO, World Health Organization, levels of an array of highly toxic, heavy metals, including cobalt, chromium, germanium, lead, and then they had industrial acid buildup as well as some uranium exposure because all of that gets kicked out during the mineral processing into the air, and it settles in the dirt and settles in the water.

[00:28:59] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Siddharth Kara. We'll be right back.

[00:29:04] This episode is sponsored in part by Athletic Greens. Jen and I take AG1 by Athletic Greens every morning. We add a scoop of AG1 to a bottle of water, you shake it up. We started taking AG1 because we don't always have time to eat a balanced, perfectly nutritious meal. Some days I just eat a meat stick for lunch. That's all I got time for. That's beef jerky to the layman. So I'll take my AG1 as a quick and easy way to make sure I'm getting all the nutrients I need. Surprisingly, beef jerky doesn't have vegetables in it. Who knew? In a way that's easy for my body to absorb. AG1 is like an all-in-one nutritional insurance. Each scoop has 75 vitamins, minerals, whole foods source, superfoods, probiotics, and adaptogen. 75 different things that most of us don't even know what they are. Can you imagine sourcing all of that on your own? I cannot. I don't even how I'd find these. Plus no GMOs, no nasty chemicals, no artificial stuff in there. Taste great too. Tried similar products. Usually they're disgusting. Got to plug your nose and drink it. AG1, I won't say it's delicious. I will say it's good for a green drink. How's that? I just add one scoop of water. That's how good it is by itself. I don't need to throw in like juices. It's time to reclaim your health and arm your immune system with convenient daily nutrition, heading into the flu and cold season, or heading out of the flu and cold season, or staying in the flu and cold season, which is what happens when you have kids.

[00:30:12] Jen Harbinger: To make it easy, athletic Greens is going to give you a free one-year supply of immune-supporting Vitamin D and five free travel packs with your first purchase. All you have to do is visit athleticgreens.com/jordan. Again, that's athletic greens.com/jordan to take ownership over your health and pick up the ultimate daily nutritional insurance.

[00:30:30] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Better Help. The other day, my dad told me his friend kept him on the phone for hours complaining about his wife and all their personal issues. I'm sure that was a fascinating conversation. Look, he was probably venting, which is fine, but for advice on what to do, my dad is not the right person to go to for that. What he needs is a therapist, or literally anyone else, but also preferably a therapist. If you're going through a tough time, speaking to a therapist can help you get out of that rut faster. If you're feeling depressed, getting out of the house to see a therapist can feel downright impossible. That's why I highly recommend Better Help. You can do chat, phone, video sessions for me. I have an easier time opening up when I'm in the comfort of my own home, talking on the phone instead of in front of some stranger. Therapy is vulnerable work and Better Help understands that you're just not going to mess with everyone. In fact, some people are just downright annoying. I don't care how qualified they are. You can easily switch therapists whenever you want until you find one that you do click with. You're going to be vulnerable. So it's important you like your therapist. Better help also has group therapy sessions. You're among people experiencing similar issues. Check out Better Help's reviews on the iPhone app over 94,000 last I checked. That's a good skepticism remover. And if you're on the fence, take this as your sign from the universe to go and try it.

[00:31:38] Jen Harbinger: If you want to live a more empowered life, therapy can get you there. Visit betterhelp.com/jordan to get 10 percent off your first month. That's better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan.

[00:31:49] Jordan Harbinger: Hey, if you're wondering how I managed to book all these amazing folks from the show, all these authors, thinkers, and creators, it's because of my network. I don't like being schmoozy or gross, and I wanted to make a course about not being schmoozy or gross, but also still making connections. It's a free course. It's at jordanharbinger.com/course. It's about improving your relationship-building skills, and I've taught this to police, military, corporate. It's not cringey, it's not gross. It's not, like I said, schmoozy. No awkward strategies, nothing cheesy. It's just going to make you a better colleague, a better friend, and a better peer. Just a few minutes a day. No weird mixers, no driving across town, no parking. Many of the guests on our show already subscribe and contribute to this course. Come join us, you'll be in smart company. Again, all free jordanharbinger.com/course.

[00:32:33] Now, back to Siddharth Kara.

[00:32:36] It's horrible, but it gets worse, right? It's there's women get assaulted in these areas because it's a bunch of dudes in an unregulated wild west environment. There's death all around. There's one woman in your book that says something just so heartbreaking. I think she had a couple of miscarriages because of all the crap that's probably in the air, in the water. And she said something along the lines of, "I'm glad God took my babies, because here it's better not to be born," which is just like horrible.

[00:33:01] Siddharth Kara: It's one of the sentences that just struck me, that pierced me, and I realized the appalling truth of it. You know, for a mother to say, "I'm glad—" imagine that. Imagine a mother saying, "I'm glad my child was taken," because their life would've been hell here is basically what she's saying. And you're right, women and girls suffer sexual violence. Is anyone up the chain talking about zero-tolerance policies on rape of teenage girls in cobalt mines, and yet they're the backbone of this industry. You know, there are women and girls by the hundreds of thousands across digging, scraping, scrounging, filling sacks, doing all that work and suffering violence, sexual violence, physical violence every day. None of these companies bothered even step foot for a minute to say, "Can we make sure the young girls here are safe? The women are safe," quite apart from all the other horrible things that are happening.

[00:34:00] So yeah, there are certain sentences that were said to me that, you know, stand for the voice of a million. There's a truth in them that is just so undeniable and representative of what's happening there. And that was one, Priscille who said, I'm glad God took my babies because here it's better not to be born." What that sentence represents in terms of the utter failure of the global economy, the utter failure of contemporary human civilization that a mother would be brought to that conclusion is something that really should be reflected on by all of us.

[00:34:35] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I mean I, that was one where I'm like, okay, stop the tape and just like take a couple of deep breaths and go get some water. I mean, I really had to, because I'm a parent of young children and I would never think, "Oh, I hope my kids die instead of living here." I mean, because I live in Silicon Valley, which ironically is where we design things that use all this freaking cobalt. It's so sad that any mother would ever think, "I'm so glad my children died because then they would've just had a horrible life and died anyway." It's so, so sad.

[00:35:06] Siddharth Kara: It's heartbreaking. And that's the pain. That's the pain that's in every battery we plug in. You know, that's the cry of agony from a mother. Every time we plug it in, we're plugging in that torment, and it doesn't matter what the tech and EV companies say, they're talking fiction until they get on the ground and see for themselves. And I've done this a hundred times and I'll do it as long as I have breath, I have open invitation. Any tech executive, CEO, C-suite, whatever you want to see how the cobalt is mined, how your cobalt is mined, I'll take you to the Congo, you see it for yourself, hear the voices of these people, and then stop putting out marketing puffery that the supply chain is clean and let's get to the constructive business of actually protecting the dignity of these people, addressing all this pain and torment and cleaning up their environment that they're going to have to live with when the cobalt scramble is done and everyone's moved on to the next thing. What will the Congolese people be left with? But dirt, a toxically destroyed environment.

[00:36:12] Jordan Harbinger: Who runs these mines on an international level, right? So they're artisanal. So it's individuals, but then they give the cobalt to who, who gives it to who, who gives it to who, who gives it to whatever Tesla or the battery supplier for Tesla.

[00:36:26] Siddharth Kara: So the supply chain works like this. And one of the things I really spent time on trip after trip was understanding and tracing the supply chain, because the companies at the top rely on the ability to describe impenetrable wall that exists between their supply and all this other activity. And just as a rational matter, if you have hundreds of thousands of people digging out tens of thousands of tons of cobalt, if it's not in the formal supply chain of these companies, where is it all going? I mean, it's not just being dug for sport. It's not going to some other planet to their tech companies. Where is it all going? So there's this informal shadow economy beneath the formal economy. You have a child in a pit covered in toxic grime, digging cobalt, filling a sack. That child will sell a sack to a trader for a dollar or two or something called a buying house, a depot, or their agents for mining companies for a dollar or two. Either way, either the middleman trader or the buying house, they sell it to the formal mining company, full stop. That's it. It's not that they sell it to some other supply chain, some other planet, some other place. It's not going anywhere but into the formal supply chain because there's this massive demand-supply imbalance.

[00:37:47] Now, once they sell it to the industrial mine, that sack of cobalt or is mixed in with the industrial production in a preliminary processing stage because Cobalt's never found by its own in nature, it's attached to copper, nickel, sometimes silver, sometimes uranium. So those little different metals have to be separated before it can be exported from the country because each one has a different royalty rate that has to be paid to the government. Anyway, they use sulfuric acid to separate the metals, and then it's exported up the chain and into the batteries. So it's that shadow economy of these informal depots that basically launder child-mined cobalt into the formal supply chain.

[00:38:30] Jordan Harbinger: What do they do with the so-called waste products? They're not going to throw away silver, copper, and especially uranium. I mean that stuff's super valuable too.

[00:38:37] Siddharth Kara: They use all of it. Well, nickel, copper, and cobalt, which are found in the ore bodies. They're almost always together. They're all used for batteries.

[00:38:46] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I was going to say that's like a battery, the trifecta.

[00:38:49] Siddharth Kara: You know, the coppers in the battery, the nickels in the battery, and they have silver, of course, there's gold out there as well. So people are digging up a stone that's got all this valuable stuff in it. Now, the most valuable right now for the rechargeable economy is cobalt because you can get copper in a lot of places. You can get nickel in a lot of places. You cannot get cobalt in a lot of places.

[00:39:10] And those mines, you ask, who's running these mines, right? 15 of the 19 major industrial mining concessions in the Congo are run by Chinese mining companies. So they dominate mining production on the ground, and they are the primary buyers of artisanal cobalt. All the agents that buy up this cobalt at the depots, most of them are Chinese buying agents for the Chinese mining companies.

[00:39:35] Jordan Harbinger: I don't know a lot about Chinese mining companies, but what I do know about shady child labor and Chinese mining companies is they're not going to be super happy if some dude from the United States is over there taking cell phone videos and asking people questions. So I assume this was not just a book a ticket to Congo and roll around with your video camera crew, kind of thing.

[00:39:57] Siddharth Kara: No. You one does not just waltz into copper, cobalt mining capital of the world and start chatting up artisanal miners, walking around industrial mines, and snapping photos and videos. No, it's highly militarized, highly secure. So there's the army there, the Republican Guard. Most dangerously, these roving militias that are just on the payroll of the mining companies, usually Chinese mining companies that just are securing territories, securing mines, keeping people out, making sure no one's talking to outsiders. So it took me a lot of time to build ground relationships to the level that I could get into some mining areas. Many artisanal mining areas, many industrial mines, many places I never got into because it was just impossible to get by or around the guys with Kalashnikovs. But in that case, I would speak to the people working in those mines, the artisanal mins back in their homes in huts if I couldn't get into the mine. So they're heavily secured and one is not supposed to be asking questions waltzing around there. There are a lot of Indians in that part of the Congo as traders, laborers, hotel workers. So I was able to blend in because I'm Indian, more so than if I was like a white-skinned person because that immediately signifies journalist or maybe mining company executive, but they wouldn't be walking around inside the mine. They'd be sitting at a hotel somewhere. It's not easy getting there and getting people to talk because there's a lot of risk to revealing the truth of what's happening.

[00:41:26] Jordan Harbinger: I assume you had to probably bribe some folks here and there to let you do your work in any area that has the curse of natural resources like this, there's a lot of corruption. So I would imagine money talks if you're driving around and you get caught by a militia, the cops, the army, whatever.

[00:41:42] Siddharth Kara: There's a lot of corruption, of course, because this is largely a lawless, violent, poor area. So everybody's looking for their buck and that includes guys with guns, it includes people at toll crossings and checkpoints and so on. The police are always there. They first thing they do at checkpoints is ask for your paperwork because if you happen to have paperwork that isn't quite right, it's either jail or a large sum of money. And so of course, I made sure my paperwork was always fine because I didn't want to ever be in that kind of a situation. But then they'll look through your bags and they'll rummage around and eventually you have to just sort of pay a little toll, you know, quote-unquote, "for them to let go and just to move along." But there's no amount of money that will convince an armed mining official to let you in like that. It didn't work that way, that they were paid to keep people out. So, as I said, there were sometimes I managed to get in and sometimes I would talk to people outside of the mine.

[00:42:39] Jordan Harbinger: That's got to be pretty scary. I think it might have been you who said they call bribes cold drinks, so it was a little confusing because you're like, where the hell am I going to get a cold drink in the middle of the — oh, you want $10? Got it.

[00:42:50] Siddharth Kara: Yeah. The first time it happened, I was at a checkpoint and this guy started giving me a hard time, you know, about something or the other and wanted to go through all my stuff and waste half of a day. And he said, "Well, if you can give me a cold drink, you know, things will move along." And it was like halfway into the bush, I said, "What? Where are we going to get a cold drink?" And my guide told me, "You know, that's the term for paying him a little something so you can just let go and move along." And so that happens a lot as it does in a lot of developing economies. Whenever someone's in a position where they can make your life difficult. I mean, just leaving the airport often requires, you know, parting with some cash because people will just make stuff up that your paperwork isn't right or you've got something in your bag that they don't like. So everyone's looking for their buck when you're in a war-torn impoverished country.

[00:43:41] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. When I was in Egypt 20 years ago, I think it was called bakshish. And it was like everything required bakshish.

[00:43:48] Siddharth Kara: Yeah.

[00:43:49] Jordan Harbinger: And it's like it was the first word you learn when you're there because the cops wanted bakshish. Your guide wanted a little bakshish. People at restaurants wanted bakshish. I mean, the taxi driver would say bakshish, and you just learn, you hear that word all day the whole time. I mean, it became like a meme, like a joke. Like, you'd give your friends something and you'd say bakshish and you know, you'll start laughing.

[00:44:10] Siddharth Kara: It's how the economy works, you know?

[00:44:12] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:44:12] Siddharth Kara: In certain parts of the world. And you either come to terms with it or you're just not going to get much done or get, get moving very far.

[00:44:19] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned paperwork. Did you need like a letter from the president or something? I mean, how do you even get paperwork that says that you can be there?

[00:44:27] Siddharth Kara: Yeah, the visa process is pretty extensive. I mean, it takes months. You have to get someone who's a local Congolese citizen who offers an invitation letter and then that letter has to be stamped and certified at the local government office. You have to show a certain bank balance and so on. And then all that paperwork gets sent to the embassy and then, they sit on it for like two months and then it gets sent back and it gets approved in Kinshasa, the capital of Congo. And then, you have to start this process months in advance. It's not like you can just say, "All right, I need to get into Congo and start running around next week." The whole process takes time. Unless maybe, if you're a VIP or a diplomat or you're coming in as part of a major news network and so on, probably, those things are formal and move along more quickly, I imagine but just someone who wants to come to Congo, it takes some time.

[00:45:15] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I suppose it's how readily you can access somebody at the embassy because I would imagine if you take that guy out for a nice steak dinner once a month or something like that, your visas get approved in 24 hours.

[00:45:25] Siddharth Kara: Yeah.

[00:45:25] Jordan Harbinger: Definitely experienced that kind of thing before.

[00:45:27] Siddharth Kara: Yeah.

[00:45:27] Jordan Harbinger: How did you have ground support? Are there local activists that also realize just how terrible this situation is?

[00:45:33] Siddharth Kara: Yes. There's a very, very thin civil society in the Congo. It's perilous work standing up for human rights in the DRC, speaking out against corruption or lawlessness or any violation of human rights. So that was my starting point, was a couple of, not even organizations sometimes, but just people who were quiet activists and I would establish relationships, build trust because these are people who then live and work in the mining communities. So through them I was able to gain access to people, talk with them, understand their truth, and then move around in artisanal mining areas in the major towns and villages, and ultimately into some industrial mines as well. In many cases, there's a way in these mines. This is what people have to understand, some of these mining concessions are enormous. I mean, the biggest mining concession in the Congo is about the size of London.

[00:46:27] Jordan Harbinger: Geez.

[00:46:28] Siddharth Kara: That's insane. That's right. You can see these things from out of space. I mean, that's a swath of territory under the control of a single mining company that is largely gouged up. Imagine the number of trees that used to be there. Gouged up for this sort of ransacking of valuable metals needed for the rechargeable economy.

[00:46:49] Jordan Harbinger: Is mining the majority of the income for Congo, the country?

[00:46:53] Siddharth Kara: Yeah.

[00:46:53] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:46:54] Siddharth Kara: It's at least 70 percent of the government's income is mining in the southeastern provinces along the Zambian border. I mean, there's not much else that generates money in the Congo. It's not like it's a tourist place. I mean, they've got timber, you know, they've got seafood, they've got some petroleum. They still have rubber, of course, but it's all mining for the last 12 years, especially cobalt.

[00:47:17] Jordan Harbinger: So it's just extract, extract, extract. Oh, man, that poor, that poor country.

[00:47:21] Siddharth Kara: Yeah.

[00:47:21] Jordan Harbinger: I assume the government then also doesn't like this. So whatever sort of support you have or letter you have, I mean, you now are never going to go back there. You can't ever go back to the Congo.

[00:47:30] Siddharth Kara: Now, that Cobalt Red is out. It will be challenging. I'll have to get a sense from people locally, whether and when it might be safe to move around. I mean, my hope is because ultimately the blame for this human rights catastrophe sits squarely at the top of the chain.

[00:47:48] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:47:48] Siddharth Kara: Demand for cobalt by tech and EV companies is what has created this entire chain of atrocities. If that demand wasn't there, we wouldn't be talking and no one said, you must use cobalt, right? It works for the purposes they need better than anything else. And the cobalt all happens to be in some place, and so that started this cycle of misery. It could have been done right from the outset, but it wasn't. So that's where I assigned the lion's hare of responsibility. There's responsibility at the Congolese government level as well because there is corruption and there is a misallocation of resources. But my hope is now that the voices of the Congolese people are being read around the world. That major stakeholders will see fit to sit down in a constructive way and solve these problems. And I'm happy to help and happy to get back on the ground and do whatever I can to help steward this energy that's being released by the book into something constructive for the people in the Congo.

[00:48:45] Jordan Harbinger: You talk a lot about the Chinese mining companies in the book, and we don't have to get into too much detail, but basically it's like a slave operation in many ways, and there's lot of corruption, a lot of adding insult to injury in terms of the way they treat their workers. And I want to be clear, we pin a lot of this on the Chinese mining companies because they're the buyers. But we are then, like you said, buying our electronics and phones from the Chinese so they're on the front line, sure. But we are the end user. And you can't really blame a drug dealer for a drug issue because the end user has to take some responsibility too.

[00:49:15] Siddharth Kara: Yeah, that's right. I mean, they are the inevitable consequence of a chain, a value chain that says, "I want maximum resources at minimum cost." Okay. And so the inevitable consequence that of that is the most vulnerable people are going to be exploited, the most downtrodden people are going to be degraded and the resources are going to be pillaged. Now, had the opening sentence been, "We need this resource, let's do it in a way that adheres to the proclamations we make—"

[00:49:47] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:49:47] Siddharth Kara: —that it's done with dignity and respect and all of this business, we would not be having this conversation. We would be having a completely different conversation about how uplifting and empowering the rechargeable economy has been for the people of the Congo, not how destructive and ruinous it has been. So everything is a consequence of an economic order that made a declaration, "I want that at minimum cost. Do what you must." But that said, it's not like these Chinese companies were operating in some magnificent manner beforehand.

[00:50:20] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:50:21] Siddharth Kara: They don't maintain human rights standards. You just look at what's happening to the Uyghurs in Xinjiang province, and when you're on the ground, there's just this animus, you can sense it, this animus that the Chinese have. I mean, I'm speaking generally because I've spoken to some of the people working at these companies, some of the middle management people, and there's just this racist undertone, not unlike the racist undertone the Europeans had when they first arrived in Africa. It's all the same, but it means that there's this callous disregard for the dignity of the people who were there, let alone preservation of their environment.

[00:50:54] Jordan Harbinger: Are there any American companies operating there in Congo?

[00:50:58] Siddharth Kara: No. Not one.

[00:50:59] Jordan Harbinger: Not one. Wow.

[00:51:00] Siddharth Kara: The last time there was an American mining company operating in the Congo was 2006. They had the biggest concession actually in the Congo. This is Freeport-McMoRan. And they sold it to a Chinese mining company called China Molybdenum for two and a half billion dollars at the dawn of the cobalt explosion. It was an awkward try. I actually spoke to one of the executives at Freeport who ran that concession called Tenke Fungurume for Freeport. And I said, "Why? What? What was the thinking here?" Because surely you could see where things were going. And you know, he said, and I write about this in the book, "Freeport was on the wrong side of some oil and gas bets, and they had made a commitment to the market to have cut in half the companies debt load and that meant selling assets. And this was one of the prized ones that they could get a nice price for." So they sold it to CMOC, China Molybdenum. And China Molybdenum is now one of the biggest cobalt-producing mining companies in the world.

[00:52:01] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest, Siddharth Kara. We'll be right back.

[00:52:06] This episode is sponsored in part by Peloton. Trying a new workout is like learning a new skill. It can be overwhelming, and the uncertainty can be a major barrier to actually getting started. Peloton's approach to convenience is very helpful for people who are looking to take on a new fitness skill or routine. Everything is designed to be as simple and streamlined as possible from the easy-to-use touchscreen interface to the wide range of class options and personalized recommendations. You can access a variety of live and on-demand classes, including cycling, running, strength. Now, there's an incredible rower, which I really enjoy, all from the comfort of your own home. Rowing is great as a full-body workout, which means you'll be engaging multiple muscle groups at once, including your legs, core, arms, and back. This will help you burn more calories. Of course, it'll help you build more strength especially, and improve your overall fitness. Correct rowing form isn't intuitive, at least it certainly wasn't for me, and doing it correctly is harder than it sounds, especially once you start getting tired because, of course, your form always breaks down when you get tired. Form Assist shows you a figure of yourself as you row, and when you screw up a portion of the body, your body turns red. That's a good way to avoid getting super, super injured or tweaking something and not being able to work out, which stops a lot of people who are diving in either for the first time or getting back into it after a long time. So try Peloton Row risk-free with a 30-day home trial. New members only. Not available in remote locations. See additional terms at onepeloton.com/home-trial.

[00:53:30] This episode is also sponsored by European Wax Center. Don't wait for spring break to get away. Book your smooth escape with the wax experts at European Wax Center. I see what they did there. This spring, whether you're going far away or sticking close to home, the relaxed confident feeling you're dreaming of is closer than you think, just visit your local European Wax Center. Can't afford to go to Europe? Go to European Wax Center. Better smooth than not a prickly cacti. Am I right? It would be cactus, I think, unless you're more than one cactus. European Wax Center are the experts in waxing for everyone. It's where I go to get things waxed. I'll just leave it at that. Every time I visit a European Wax Center, I know I'm in good hands, literally. Their certified wax specialists are expertly trained and they're very friendly while they're ripping out your hair brutally. I mean, there's only one way to do it effectively. You wouldn't want your hair ripped out any other way, let me tell you. The experience is surprisingly not painful, like I'm sort of hinting at, or like you might expect, their secret is their signature comfort wax. It's a proprietary blend of beeswax sourced from Europe and other skin soothing ingredients that allows them to remove hair easily. The wax only sticks to the hair and not to your skin, and trust me, that's important, folks. I have little bit of spider legs in the nose. A nose trimmer just can't compete with the wax. That's the service I often go for. The wax experts at European Wax Center can help you with your browse, your shoulders, your legs, your back, wherever you got hair, folks. I don't want to know. They offer personalized consultations so you can find the wax that works for you. So book your smooth escape with the experts at European Wax Center. Make a reservation today. Your first wax is free.

[00:54:56] This episode of The Jordan Harbinger Show is brought to you by Nissan. As a pioneer in the electric vehicle space, Nissan is always looking for ways to deliver new, meaningful technology to EV owners. After all, Nissan has been making EVs since 1947 and their EVs have now traveled eight billion miles by Nissan LEAF owners since 2010. Eight billion miles, that's the equivalent of driving to Pluto and back. I guess it, I don't know, doesn't matter if it's a planet, maybe when we're doing this. Think that's electrifying? One of their EVs tracked all the way to the North Pole, and Nissan even tests their EV technology on the Formula E racetrack. But Nissan knows you can't get an EV just for the E. You get a Nissan EV because it makes you feel electric, because it sparks your imagination. It ignites something within you. It pins you to your seat, takes your breath away. At least that's what Nissan thinks about when they're designing their EVs, like the Nissan ARIYA and the Nissan LEAF. It's about creating a thrilling design that electrifies its customers. I like Nissan's focus on creating a thrilling drive and electrifying life. In today's world, it's so important to look around you, pay attention, look for all the tiny ways that life can electrify you. For me, that's reading an audiobook outside and preparing for this show. Nissan, EVs that electrify.

[00:56:00] Hey, if you like this episode, I invite you to do what other smart and considerate listeners do, which is take a moment and support our amazing sponsors. I know you think, "Oh, this guy's got a lot of people listening to this. He doesn't need my clicks," but I really do need your clicks. That's what keeps the lights on around here. All the deals, all the discount codes are, by the way, they're all in one searchable, easy-to-find place, jordanharbinger.com/deals. You can also use the AI search bot that should pop up any promo code. You can even search for, like what's the company Jordan recommends for therapy and it should find the promo code for Better Help. That's on the website at jordanharbinger.com. Thank you so much for supporting those who support the show.

[00:56:34] Now for the rest of my conversation with Siddharth Kara.

[00:56:39] Oh, man, I mean, and this is a strategic mineral for obvious reasons, and it's just, we're totally, that's a whole different show is how we're just completely reliant on China for rare earth metals and other things like that. You mentioned the Uyghurs and the way they're treated by the CCP, that's episode 730. We did a whole show about the Uyghur genocide with the Uyghur attorney.

[00:56:59] Is there other significant industry in Congo? Because where there's mining, I mean, you already mentioned that the rivers are polluted, I would imagine you can't farm very well if people are digging your land up and dumping acid all over it.

[00:57:11] Siddharth Kara: You know, with each trip I took to the Congo, each time I went back, the people living there were being pushed further and further into the fringes because the mining concessions just kept growing and growing and growing. It's that supply-demand imbalance again. It just kept taking over more countryside, more land, and that was cutting down agricultural land. Entire lakes and rivers were disappearing. So people are pushed more and more to the fringe and there's literally almost nothing else people can do there to survive other than dig and hope to get that dollar or two for that day, which is the difference between eating or not. So when agricultural land is destroyed or polluted, when entire villages are bulldozed and people are displaced and left defend for themselves, you have this cycle, degrading cycle of vulnerability and poverty that leads entire families, including children, to just scrounge back onto the land they used to live to try and get a sack or two of cobalt to earn those few dollars because that's how they'll eat that day. And so they're living day to day just to survive. And that's the reality at the bottom of the rechargeable economy.

[00:58:21] Jordan Harbinger: In your opinion, why isn't this problem solved? Would it be prohibitively expensive to do this in a way that isn't horrifying?

[00:58:29] Siddharth Kara: It would be a rounding error on the balance sheets of tech and EV companies to solve this.

[00:58:36] Jordan Harbinger: Really?

[00:58:36] Siddharth Kara: And it could be done relatively quickly and easily. I mean, some of the simple things that could be done in a week to eliminate more than half of the harm that's taking place is buy some PPE for these people, boots, gloves, goggles, masks. It's a one-time cost. How much does a suit of PPE cost for a person? One time, not that much, right? That cuts down their daily toxic exposure to cobalt, that buildup of heavy metal that they're suffering. How about pay people a fixed, simple daily wage. Instead of earning two dollars in a day, that is not enough to survive. Pay people a day wage of $10, $15. Now, they don't have to bring their children into the mine to dig, to try to earn another two dollars because mom and dad are getting a decent wage that's enough for the family to eat, have clothes, and keep the kids in school. $10 a day, bankrupt Apple, Tesla, or any of these companies? They wouldn't notice it. It's a de minimis sum to them to pay their Congolese employees who are digging their cobalt out of the ground, a basic surviving day wage plus some PPE.

[00:59:43] Jordan Harbinger: Does the day wage solve the problem? I mean, look, I'm not trying to pop a hole in this, but like people say, "Well, you can't just give people more money because then you know, you'll have inflation which will just end, you'll end up with the same problem.

[00:59:54] Siddharth Kara: That day wage is what helps keep children in school, and that solves a lot of the child labor problem. And most people, they're just bringing children in. They don't have a choice because they need that extra two dollars to survive. Every parent there that I ever spoke to understands the importance that their children should get in education, but as a matter of basic survival. So pay them enough to keep the children in school. And that solves a lot of the child labor problems. It also enhances future development for the entire community. Why not build a few schools? Do you know how expensive it is to build a few schools? It's not much. It's a concrete structure with some chairs and buy some books and a teacher. Build some schools while you're at it. How about expand sanitation so we can reduce waterborne illness? And so there's so many things you could do to support and help those communities that don't cost that much and would make a huge difference in their basic livelihood. If they're getting a basic dignified day wage of 10 or $12, there's not this push to dig those tunnels to try to get the higher grade that's going to give them four dollars. And then all the associated suffering that comes with that is eliminated. That doesn't solve the problems. There's still other issues relating to the environmental impact and making sure mining companies operate sustainably. There's local corruption that would've to be dealt with, sexual violence would've to be dealt with. There's a lot of other things, but there's some immediate low-hanging fruit that could be deployed very quickly to eliminate a substantial amount of the day-to-day harm that people are suffering.

[01:01:22] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like a relatively simple proposition compared to the problems that Silicon Valley geniuses have solved that end up using these minerals. Like look at a smartphone in how amazing this device is. It seems far more complex than solving for basic human dignity at the bottom of the supply chain.

[01:01:39] Siddharth Kara: I couldn't agree more. Actually figuring out how to manufacture that smartphone or an electric car and erect the supply chains and all of that efficiently, that is way more complicated than figuring out how to maintain basic dignity for a people in the Congo. That's a simple problem. It's a simple problem. So the question, Jordan, is why haven't they done it and that comes back to this uncomfortable truth, that the perception is they're not worth it. They're not worth the effort, they're not worth the attention. They're not worth the modest amounts of money required to transform and improve conditions at the bottom of these supply chains. And that's been the curse of being African for generations, for centuries, that they're somehow perceived to be worthless. "Oh, yeah, they don't mind taking their kids to work because parents don't care over there." I mean, this is the nonsense that you hear at the top of the chain. No, they love their children as much as we love ours, they want a better life for their children just like we do. But treating them as if they're somehow worthless, feel less, careless and that their environment can be sacrificed in order for us to preserve ours with this green transition to EVs. All of that is predicated on the assumption that they aren't worth the same as us.

[01:03:05] Jordan Harbinger: Right. There're expendable. Yeah, it's so vile. How close are we to, I don't know, cobalt-free batteries or is that like a wind farm that runs without wind?

[01:03:15] Siddharth Kara: There are cobalt-free batteries that are being used in some EVs right now.