“Nothing is as obnoxious as other people’s luck,” said F. Scott Fitzgerald, which is actually pretty funny, considering he’s one of the greatest American writers in history.

But maybe it’s funny for another, more disturbing, reason: If F. Scott Fitzgerald wasn’t above envy, what hope is there for the rest of us?

We don’t talk much about envy as a society. There aren’t a ton of self-help books about it, and it’s not exactly a conversation-starter at dinner parties.

Who wants to cop to wanting what someone else has? Who wants to open up about resenting a friend’s success?

The answer is approximately no one, despite the fact that Instagram and Facebook and most of TV are basically one nonstop envy-palooza.

And so envy becomes another one of those secrets we all share. And as you know, whenever I find a secret we all share, I know it’s time to talk about it.

Like all ugly emotions, envy can be insidious and paralyzing. It wears us down. It consumes us. It hurts. But it also contains a ton of information about who we are on the deepest level.

In that sense, it’s a gift. We just need to know how to unwrap it.

In this piece, we’ll be exploring the mechanics of envy, why and how it functions in human beings, and — most important — how we can use it to become happier and more fulfilled people, rather than allowing it to use us.

How Envy Really Operates

We all know what envy feels like on a gut level, because envy is a non-negotiable part of the human experience.

But if we open the hood and look inside, we find that envy is actually a complex and layered experience, with a few different moving parts.

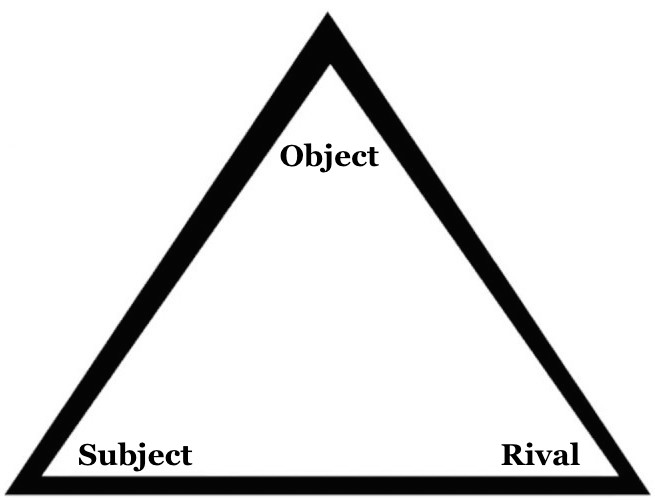

Aristotle put it nicely when he defined envy as “pain at the good fortune of others.” The Greek granddaddy of ethics zeroed in on the three elements of the envy equation: you (subject), the other person (rival), and the object — that is, the thing you want — which all conspire to create a curious sense of “pain.”

Of course, the “object” or “possession” in question can be anything: a person, a skill, a talent, a relationship, a form of wealth, an idea, a plan, a personality, and so on. Anything that we can value could be an object of envy, as long as someone else wants it.

But without that other person — without a “rival” in the picture — envy would just be a simple desire. It’s the presence of the other person in the triangle that turns a typical longing into the charged experience we know as envy.

In other words, envy can only exist in the relationship between two people.

It’s the relationship between “subject” and “rival” that activates the experience.

But there’s still something missing from this definition of envy.

Immanuel Kant filled it in when he said that envy is the tendency “to view the well-being of others with distress, even though it does not detract from one’s own” (my emphasis added).

Which is a really interesting point.

When envy crops up in our lives, it often contains two different desires within it: desire for the thing we wish we had, and a desire to “beat” the person who has it.

These two sub-desires quickly get collapsed, because the quickest way to “win” against a rival seems to be to possess the object in question.

At least that’s what envy wants us to believe. But we’ll get into that in just a moment.

Subject (us), rival (the other person), object (the possession we want) — these are the three points in the envy triangle.

But people disagree about which side of the triangle actually creates the experience of envy.

Some people think that the object of envy is the person who has the thing you want, while others believe that the object of envy is the thing they possess.

In other words, envy could be about wanting something we don’t have, or it could be about being someone we wish we were.

Or maybe it’s both, and wanting the thing is really just a clever way of trying to become the person who has it, as the philosopher René Girard famously argued.

In Gerard’s view, when we long for the promotion that our colleague at work got, we don’t really want the promotion. What we actually want is to be her. The promotion is just a “mediator” — a sort of connective bridge — for our real desire, which is to embody the qualities she possesses.

Which does explain a lot about why we’re so preoccupied with the people who have the things we want, in addition to the things themselves.

As theorists have pointed out, this kind of model explains why our pain often goes away — along with our desire to possess the object of envy — if our rival happens to lose it. No rival, no envy.

Do we envy something because we truly want it, or do we envy it in order to become someone else? If someone else didn’t want it, would we still envy it?

But we don’t need to take a firm stand on this.

We just need to understand that when these three elements come into contact — a subject, a rival, and a possession — they create the conditions for envy.

That envy can be focused on the possession, on the rival, or both. Sometimes it can toggle between the two. Sometimes it can focus on both at once.

Two people and a thing: That’s all we need for one of the most complicated human emotions to take root.

Envy vs. Jealousy

Although we often use the terms interchangeably, envy and jealousy are actually two different emotions.

Envy and jealousy both operate in the same subject — rival — object triangle, but their primary concerns are different.

While envy is about wanting what someone else has, jealousy is about hanging onto something we don’t want to lose.

In other words, when we feel jealousy, the primary object of concern is not the rival, but the possession — our possession — a thing we fear losing to someone else.

Marcel Proust called this “the insensate agonizing need to possess exclusively,” which pretty much nails it.

Envy, on the other hand, is about wanting to have someone else’s possession, which means the primary object of concern in envy is actually the rival and their object.

Of course, envy and jealousy intersect all the time.

When Company A launches a hostile takeover bid for Company B, Company A might envy what Company B has — its customers, its products, its markets, and so on.

But Company B can guard those assets jealously as it tries to fend off the envious takeover bid.

Both parties are interested in what Company B has, but their relationship to that interest is different. Company A attacks out of envy, and Company B defends out of jealousy.

The same principle applies to lovers, friends, colleagues, and parents. In every area of life, we find people battling in this fraught triangle, contending with their envy or their jealousy, or both.

Which is what led Warren Buffett to one of his most important beliefs.

“It’s not greed that drives the world,” he said, “but envy.”

Word, Warren… word.

The Two Types of Envy

But not all envy is created equal.

As we know, envy can be mild or all-consuming, aspirational or self-loathing, inspiring or debilitating. It can drive us to achieve or it can bury us in resentment.

Are all of these species of envy really the same beast?

Definitely not, say most experts.

In reality, there are two kinds of envy: “benign” envy and “invidious” envy.

Or, to put it even more simply (as you know I like to do, because I’m clearly envious of people who can track big words!): there’s “good” envy and “bad” envy.

“Good” (benign) envy refers to a kind of envy that admires someone else’s possession and tries to emulate the qualities of the person who owns it.

If you’ve ever looked at someone successful in your field and thought, “Man, I wish I had that kind of career, I would love to be the kind of person who loves what they do and works that hard,” then you’ve experienced this brand of envy.

Benign envy draws you deeper into ambition, achievement, and admiration, rather than keeping you in the raw longing of envy itself. The “rival” is still part of the triangle. But in benign envy, the rival is helping you see the value of the object in question and the qualities that make its possession possible.

In benign envy, you and the rival could conceivably both possess the object, and all would be well in the world.

More importantly, benign envy can actually drive you to pursue the object of your desire even more passionately. It often becomes fuel for action.

“Bad” (invidious or malignant) envy is a very different experience.

Invidious envy can include elements of benign envy, but with the additional desire that the rival lose the possession in question.

In other words, it’s not enough that you possess the object of your desire. You also want to see the other person not have it, too.

If you’ve ever looked at someone successful and thought, “Man, I should have that kind of career instead of him” — or fantasized about a rival’s failure as you imagine your own success — then you know how different this brand of envy is.

Invidious envy doesn’t just operate differently. It feels different.

It amplifies the associated distress, and it shifts the world into a zero sum game. The side of the envy triangle that connects you with your rival stars to vibrate at a much higher frequency. The thing you want still matters, but part of the reason it matters so much is that only you can (or “should”) be the one to own it.

As per yoozh, there’s disagreement here, too.

Some theorists say that benign envy isn’t really envy at all, but more like a very strong desire.

In fact, what we call “benign” envy might actually just be “respect” or “admiration.” After all, the fact that someone else possesses the object we want doesn’t automatically mean that we envy them. They just happen to be in our field of awareness.

Which, fair enough.

But then what makes envy envy?

At what point does desire tip over into this noxious drive to win something at someone else’s expense?

In my view, it all comes down to our experience.

If there’s pain involved in a desire — if longing for something brings up distress, anxiety, hostility toward others, self-loathing, and so on — then there’s a good chance that the desire has taken on the contours of envy.

But I’m not just talking about low-grade pain here. You might look at a pair of Prada shoes on the rack and feel a vague aching or dissatisfaction at not owning them. I wouldn’t call that envy.

But if you see a friend of yours rocking those Pradas and feel that pain — not just because you want them, but because they have them and you don’t — then you’re probably entering the territory of envy.

(And if you’re not a shoes person, substitute “new BMW,” “trip to Barcelona” or “happy relationship.” The dynamics of envy are exactly the same, no matter the object. Although it’s fascinating to notice how envious we can get about the smallest things!)

“Mere regret at not possessing something which belongs to another … is not enough in itself to give rise to envy,” said the philosopher Max Scheler, “since it might also be an incentive for acquiring the desired object.”

Clearly, Scheler had something like benign envy in mind.

But “envy,” he said — and he probably meant something like malignant envy here — “occurs only when our efforts to acquire it fail and we are left with a feeling of impotence.”

So maybe that’s the boundary between desire and envy: if you experience pronounced pain — including that feeling of impotence or paralysis about achieving the thing in question — because someone else has what you want.

From there, that envy can stay in the realm of benign envy (perhaps motivating you to work harder to cop those Pradas), or it can metastasize into malignant envy (stewing in resentment that you don’t own them, and wishing that someone else didn’t).

That’s what Shakespeare meant when he called envy “the green-ey’d monster” that “mock[s] the meat it feeds on.”

The “meat it feeds on,” of course, is us — our happiness, our health, and our view of the world.

The philosopher Sara Protasi goes even further. She argues that there are actually four different types of envy: emulative, inert, aggressive, and spiteful. These categories cut across benign and invidious envy, and dig into the subtle motivations and behaviors that underlie them. It’s an awesome taxonomy, although at the end of the day, envy always operates under the same basic architecture — the triangle we talked about a few moments ago.

Once again, we don’t need to pin this down with scientific precision.

It’s more important that we appreciate the contours of envy, so we can see how it operates in our own lives. All we really need to understand is this.

- Desire and envy are different. Sometimes the boundary between the two gets blurry. Sometimes desire leads to envy. Often they co-exist.

- Desiring something that someone else has can trigger envy. Sometimes it’s the presence of the other person that converts desire into envy, but not necessarily.

- Sometimes envy is about the thing we want, and sometimes it’s about the person who has the thing we want. Oftentimes it’s both.

- Envy can take on a benign form or a malignant form, depending on how it functions in our psychology and how much we care about what other people do or do not have.

- Envy can manifest differently in different people in different contexts, driving us to emulate, settle, pursue or aggress, depending on our behaviors and motivations.

- No matter what kind of envy we deal with, it can be strong or weak, overwhelming or manageable, debilitating or motivational. There are degrees to envy; there are ebbs and flows.

But if we were really honest with ourselves, we’d probably have to admit that envy is usually strong, debilitating, and deeply unpleasant. If it weren’t, it wouldn’t be such an object of fascination, and we wouldn’t try so hard to avoid talking about it.

So let’s talk about it.

Specifically, let’s talk about how to handle it, manage it, and turn it into something we can use to enrich our lives.

How to Deal with Envy

Know that envy is normal and hard-wired.

Though it’s painful, petty, and sometimes straight-up embarrassing, envy actually has important evolutionary roots. These roots go back hundreds of thousands — maybe even millions — of years.

Consider for a moment why our species developed the tendency to worry about what other people have.

In a world of finite resources, and in communities that are by nature competitive, the person who can keep tabs on how much food, social standing and security they have relative to other people would have a major survival advantage.

That’s what researchers Sarah E. Hill and David M. Buss explain in their work, where they argue that social comparison actually helped keep our species alive.

Along the way, selection created a number of cognitive processes that are obsessed with how we much have relative to other people — people our ancient brains automatically view as rivals.

Not only that, the team points out, but self-comparison also plays a huge role in our own self-evaluations. We look at what other people have, tally up what we don’t have, and then use that comparison to make a profound judgment about our own status and self-worth.

Neuroscientists have actually mapped this experience to specific regions of the brain. One of the regions most profoundly affected during bouts of envy is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which is associated with conflict and error detection.

When the ACC finds a gap between an expectation and a result — as we do when we look around and see people having more than we do — it gets activated.

Interestingly, the ACC also shows activation when it experiences the pain associated with another experience: social exclusion.

If this process sounds oddly familiar, that’s because it is: We feel it every single time we scroll through our Instagram feed.

This, multiple researchers have shown, is how social comparison and envy get intertwined. It’s also why comparing ourselves to other people makes us suffer.

All of this is hard-wired into our DNA. We don’t need to self-compare as a matter of survival anymore, but we still do — and experience the pain of envy as a result. It’s almost as if we have no choice. Our brains are simply designed to do this petty comparative math, and our personalities pick up the emotional tab.

So whenever I’m hit with a pang of envy — which, let me reassure you, still happens even to me from time to time — my first move is to take a step back from my primitive mind and notice what it’s doing.

“How funny,” I’ll think, observing my Homo sapiens brain trying to make sure it’s gotten its fair share of the hunt. “There it goes obsessing about what other people have, instead of appreciating what I do have.”

Immediately, the envy begins to lose its gravitational pull. From there, I can separate out the automatic cognitive process from my true feelings about the situation at hand.

If we remember how much our negative emotions are driven by outmoded biology, it becomes a lot easier to put them in perspective — the crucial first step.

Use envy to teach you what you want.

Envy can be extraordinary useful in teaching you what you want. Beneath the layers of distress and shame, at the core of all envy is desire — a desire that is important to understand.

Laney, a recent client of ours, shared her newfound sense of envy as she progressed in her career as a talent manager in the music industry, managing bands as they recorded albums and built their followings.

Until she found her calling in this field, she hadn’t experienced very much envy in her life. But now that she was on a path she loved, she was struck by acute moments of profound envy when another manager scored a big win for their client, or when she met a successful manager a few rungs above her on the ladder.

The feeling had gotten so acute that she found herself avoiding these interactions entirely. She worried that that avoidance was getting in the way of her networking and self-development, so she asked for help.

“When you find yourself feeling that envy,” I asked Laney, “what do you think you’re really longing for?” She blinked back at me, uncertain. “Like, what’s the desire underneath the envy?”

Laney thought about that for a moment, then started talking.

“To be part of that kind of success, I guess. To be that connected with my clients. To know that my involvement matters.”

As she spoke, a small smile played on her face. It was almost as if the distress of the envy had evaporated, and the desire at the heart of her envy was animated every word.

“It sounds like those accomplishments are really important to you,” I told her.

“Yeah, I guess they are,” she responded, almost surprised. “I thought I just wanted to be seen as successful, but I don’t. I actually want to be connected to my clients in a meaningful way. And I don’t feel that all the time.”

In just a few moments, we had excavated Laney’s envy to reveal the crucial information it contained: a better view of her own goals, desires, and priorities.

The pain of her envy ratcheted down, and the motivation to pursue her goals faded up. In our brief conversation, she had gone from malignant to benign envy. By studying her envy rather than running from it, she got a deeper perspective on who she really is.

Here’s the thing: Envy isn’t fun. It isn’t immediately productive or easy to discuss. It’s tempting to suppress it in order to avoid the shame and discomfort of wanting what someone else has.

But if we can sit with it, take it apart, and look at what’s really driving it, then we can actually use our envy as a kind of beacon pointing us to what really matters. The moment we do that, our envy becomes a powerful teacher.

When Laney emailed me a few months later, she said that her relationships to her clients and peers had changed dramatically. Interestingly, she said that her envy hasn’t disappeared entirely. But her relationship to her envy had shifted.

“Now when I feel envy about someone’s success, I ask myself why. And the answer is always because they are chasing something I want too. I zero in on what that something is, and I remember how much I really want it, and then I ask myself what I can do to right now to act on my desire. And then I do that thing, right there in the moment, and it’s almost like the people I envy are telling me what to do.”

The path from malignant envy to benign envy is introspection.

When we study our envy, we begin to chip away at the negative emotional field surrounding it, and dig deeper into the positive frequency around the underlying goal.

Every instance of envy contains that possibility. Every moment is designed to teach us more about ourselves. We just have to dig deep enough to listen.

Recognize what envy does to other people.

When we talk about dealing with envy, we usually talk about what it does to us. How does it make us feel? How can we stop envying other people? Why does it happen to us?

But the other side of the envy equation — the side of the “rival” — is also worth exploring. How does our envy affect the people around us?

“The worst part of success,” said Bette Midler, “is trying to find someone who is happy for you.”

I laughed at that quote for a long time before I realized the tragic truth behind it. Success, like failure, can be a lonely experience for many of us, largely due to unchecked envy.

As we’ve seen, envy turns a person who has what you want into a rival.

Just by possessing something of value, that person automatically becomes a competitor, all because of the dull reptilian calculations of our ancient brains. We struggle to see our rival as a full person who just happens to have an object we want. We only see them as an obstacle to our possession, and — when our envy becomes malignant — someone to tear down on the way to acquiring it.

In turn, we deprive ourselves of their presence in our lives. They become sources of conflict and distress, rather than friends, colleagues, role models, and teachers.

Think about Laney: Before she studied her envy, all she saw were anxiety-provoking rivals. Afterward, she found peers and role models who revealed what was possible and motivated her to work harder.

When a wave of envy approaches, ask yourself how that envy is shaping your perceptions of its sources.

Are you viewing your “rivals” with kindness and admiration, or with fear and resentment?

Do your feelings about them align with their experience of themselves, or are you projecting your own conflict and distress onto them?

Is your life gentler and richer for viewing them with envy, or more painful and self-interested?

How do you feel when other people view you with envy? Do you feel more secure or less secure? More connected or less connected?

The answers are usually pretty clear. Notice the lens of your envy, and consciously choose not to exclusively view the world that way. The envy might still remain, but the pull to view the world through it will start to fade away, leaving a happier and more productive perspective.

Take stock of what you have.

As we touched upon earlier, our brains are specially designed to obsess over what we don’t have. They’re much less skilled at appreciating what we do have, because knowing what we already possess was far less useful for immediate survival.

In other words, we are not hard-wired for gratitude, but for scarcity.

And when we operate from a mindset of scarcity, envy becomes even more problematic, because it feeds on our built-in obsession with what we lack.

The best way to control for that obsession? Take stock of all the things you do have.

I recommend being very specific here. The next time you’re wrestling with envy, try asking yourself the following questions:

- Which unique qualities — talents, skills, expertise, personality traits — do you possess?

- Which close relationships — with family, friends, colleagues, and even yourself — enrich your life?

- Which special experiences — conversations, events, trips, opportunities — have you been part of?

- What do you have now that you didn’t have a year ago? What did you have a year ago that you didn’t have the year before that?

The more specific you are in your answers, the more you’ll realize just how much you already possess. These are assets you likely discounted or overlooked during periods of envy. When you stop overlooking them, you start to truly appreciate them — a productive use of the energy you would have otherwise spent in envy.

As you do this exercise, you might realize that these assets are the very same things other people would envy about you! (Spoiler alert: They probably do.)

The idea, then, is to admire yourself for the things you already have, almost as if you were looking at yourself as a third party. You turn your envy inward, and apply it to yourself. That is gratitude in action.

At the end of the day, gratitude is just self-envy.

And if you’re busy envying yourself for the things you already have, it’s a lot harder to envy other people for the things you don’t.

This exercise is useful in moments of acute envy, but it becomes most powerful if you make it a practice.

Set aside a few minutes each week — that’s all it really takes — to go through these questions. Make it a habit to take stock of what you have. Notice what that practice does to your impulse to self-compare. Notice how much harder it is to succumb to envy when you’re connected to what you already have.

Capitalize on the connection between gratitude and envy. Strengthen it, and watch what it does to your impulse to self-compare.

Understand that life is not a zero-sum game.

Implicit in the envy experience — especially when it comes to malignant envy — is the idea that our success and other people’s success are incompatible.

If someone else has something valuable, we tend to want it too — and we also want them to not have it. Once again, this is an expression of our limited reptilian brain, which is designed to snatch up as many resources as it can for itself. Evolutionary advantageous, but maladaptive to our happiness.

Envy wants us to believe that life is a zero-sum game: that either we have success or other people have success, but not both.

In reality, life usually doesn’t work that way. And even when it does — for example, when you’re competing for one promotion against several colleagues — we tend to ignore the ways in which we can share in other people’s success.

Ethan, a longtime listener of the show, once emailed me about this exact problem.

A talented journalist, he was wrestling with some ugly feelings of envy as he watched several of his friends get published in high-profile magazines and land book deals based on their work. He knew he didn’t want to be “that guy,” but he was that guy. How could he not, when his Facebook feed was full of people celebrating the wins he wanted so badly?

Ethan’s story reminded me of this one passage by Dante, the OG Italian poet, which really sums up the impact of unresolved envy.

Because your longings focus on a point

where company would lessen each man’s share,

envy blows up its bellows for your sighs.

Ironically, the more that envy makes us view life as a zero-sum game — “a point where company would lessen each man’s share” — the further away we get from actually achieving it. That’s what Ethan was wrestling with.

So I decided to asking him a simple question in my response.

“Besides feeling bad that you don’t have it,” I asked him, “what does their success mean for you?”

I didn’t hear from Ethan for a few days, and then I got a response.

“I have to tell you,” he began, “I had a really strong reaction to your email at first. Your question bothered me, and I wasn’t sure why. But I couldn’t stop thinking about it, and I finally wrote a few things down.”

When he was forced to look for the benefits of other people’s success, he found plenty. For example, he could ask his peers for guidance when he tried to write his own book proposal. Down the road, maybe he could even get an introduction to an agent or publisher. If he wanted to pitch pieces to higher-profile magazines, he now knew writers who had successfully worked with them. And in the bigger picture, his peers were actually showing him what was possible with enough determination and hard work.

No wonder Ethan had such a strong reaction. As soon as he started investigating his envy, his primitive brain knew it would have to give up the idea that it was losing when other people won! As unpleasant as envy is, it can also be enormously comforting. Take it away, and we actually have to acknowledge other people’s experiences, embrace our own desires, and remove a major obstacle to our own success. This is why envy can be so tough to crack.

My favorite part of Ethan’s story, though, is that he actually decided to open up about his envy with one of his peers.

Over dinner one evening, he told this fellow writer that he was embarrassed about some of the envy he had been feeling about his success, and that he didn’t want it to get in the way of their friendship.

Amazingly, his friend felt a flood of relief, thanked him for telling him all that, then told him that he had felt envious of Ethan in the past! They had a great conversation about how much envy exists in their field and how they’ve managed it in different ways, and they became closer friends for it. As always, the secret we all share lost its power the moment it stopped being a secret. The two went from being peers to actual friends that night, and are even closer today.

With this simple exercise, Ethan realized that other people’s success doesn’t come at the expense of his own. If anything, it only amplifies his future success.

But because he was locked in the narrow, zero-sum-game point of view that envy imposes on us, he couldn’t see the larger exchange of value that was taking place in his life.

What that shift, Ethan he felt inspired to celebrate his colleagues’ wins in a bigger way. He wrote them thoughtful emails congratulating them, and explaining what their success meant to him, which clearly meant a great deal to them. He gave them shout-outs on Facebook, sharing their work with his friends. When their books came out, he promoted them online and in person. And the more he participated in their success, the more he felt a renewed sense of pride in belonging to a community of peers who were doing great work.

Unsurprisingly, when Ethan landed an essay in a major magazine a year later, his fellow journalists were intimately involved, from giving feedback to submitting the piece to promoting it when it came out. None of which would have been possible if Ethan had succumbed to the limited worldview of his envy.

Just as we did with gratitude, we have to make this non-zero-sum-game mentality a practice.

We have to consciously choose to think about other people’s successes as net-positive, and find ways to celebrate them as if they were our own.

Because as long as we’re building meaningful relationships with people, they are our own — even when they’re happening to other people.

That’s a perspective that’s only possible when we stop viewing the world strictly through the lens of envy.

Recognize that envy is part of our culture.

Envy has a basis in neurobiology, but our culture has exploited and reinforced that impulse over thousands of years. Seeing how our culture conditions us to indulge our envy is an important step in managing it.

Watch an hour of television, and you’ll find dozens of commercials that play to our tendency to self-compare. A man sees his neighbor’s new car in the driveway, and suddenly you’re hearing about 0% APR on an Audi A4. A woman wonders if her apartment is as clean as it should be, and suddenly you’re primed to buy some Clorox Scentiva.

Everywhere you look, you’ll find subtle (and not-so-subtle) cues to compare yourself to other people. Marketers, more than anyone, understand just how effective envy is in selling products.

At the same time, the impulse to self-compare is a normal part of our everyday interactions.

Most of us spend a great deal of time looking over our shoulders, tracking our friends and colleagues, discussing people’s successes, and using them to judge our own. This isn’t inherently bad, of course. But when it becomes malignant and we don’t call it out, we accept toxic envy as an acceptable part of everyday life, when it’s actually something we should notice and investigate.

If envy didn’t exist, our society would break down.

It sounds dramatic, but think about this for a moment.

Would people buy as many things if they didn’t wonder if they were good enough?

Would colleagues compete ferociously with one another if they didn’t feel they needed the money to buy those things?

Would they stay in jobs that made them unhappy if they truly understood what they wanted out of life?

Would they vote for flawed policies if they weren’t so concerned with what other people did or didn’t have?

We don’t need to solve envy on a societal level. (Our own envy is hard enough!) We only need to notice how societal envy plays out in our lives every day.

As you begin to see the ways that culture reinforces this timeless impulse, you can learn to ignore the forces that want to entrench your envy even deeper. You can choose to listen to your own voice over a company’s, and value your own preferences over someone else’s. You can choose to learn from your envy, rather than looking to companies and authorities to resolve it.

Over time, it will become easier to manage the drivers of envy that are actually under your control.

Distinguish between the sources and objects of your envy.

As we discussed earlier, sometimes we envy what other people have, sometimes we envy the people themselves, and sometimes we envy both things at once.

But to manage our envy, we have to separate these elements out, so we can get clear on what they’re really trying to teach us.

I remember talking to Hannah, a recent college grad working in PR, who was working through these layers herself. When her best friend from college landed a dream job in corporate communications at a Fortune 500 company, she was surprised to find herself struck by an unfamiliar sense of envy.

So we talked it out. I asked her to identify the source of her envy, and she clearly identified her friend and her friend’s big news. I asked her to identify the object of her envy, and she pointed to the corporate communications job.

But as we unpacked these pieces, Hannah realized that her envy about the job was less intense than the envy she felt toward her friend. She wasn’t even sure she wanted to stay in PR, she explained. In fact, she was thinking about going to business school, so she could apply her PR chops to a career in human-capital consulting.

If she wasn’t even sure she wanted that career, why was the envy creeping up at all?

The answer, she realized after some reflection, was not that she wanted that career. What she really wanted was to be someone who had a great career — one she cared about, one that she found meaningful, one she could be proud of. Her envy was more focused on her friend’s general identity than the object of desire they shared.

But even her envy about her friend was more nuanced. After talking it through, she realized that she didn’t envy her friend for having something she wanted; she envied her friend for having the drive to pursue the career she wanted.

By distinguishing between the source and the object of her envy, Hannah learned to use her envy to teach her what she really wanted. She also noticed her ancient brain obsessing over what other people had, without bothering to make sure it was something she really wanted. Which is a great reminder that all of these principles are deeply connected.

Hannah seemed genuinely excited by this new insight. But I knew there was one more step to make it truly meaningful — which brings us to our final principle.

Put your envy into action.

In this piece, we’ve been unpacking the psychological, biological, and cultural foundations of envy.

Along the way, we’ve been exploring the layers of envy, and looking at all the variables that make the experience of envy so challenging.

With each principle comes a little more insight — insight about what envy can teach us, how envy gets amplified or reduced, and how envy prevents us from living generously and gratefully.

But that insight only becomes truly meaningful when we put it into practice.

And that means taking action on that insight in specific, proactive, goal-oriented ways. If there’s one principle that holds the key to dealing with envy, it’s this this one.

When Hannah realized what her envy was trying to teach her, she channeled that insight and excitement into her business-school applications. She wrote a moving essay about how her career had taught her what she wanted to spend her life doing, and shared that story with the people who wrote her recommendation letters. Her four-month application process became a canvass for her to map out her future, driven by the raw longing she discovered in her envy.

Hannah’s now working as a human-capital consultant at a major advisory firm, and says that she helps her clients understand their goals in the exact same way. Her own journey through envy is actually shaping her approach to envy at the corporate level! (Which is a great reminder that all of these ideas apply to institutions as well as people.)

Ethan, the journalist, is also a great example of putting insight into action.

When he realized that his envy was getting in his way, he made a commitment to redirect that energy into celebrating his friends’ successes, talking about his struggles with envy, and using it to push his writing forward. It wasn’t enough for Ethan to see that his envy was paralyzing him. He had to use it to propel his work forward in order to truly benefit from it.

What is your envy trying to teach you?

What are the desires, sources, and objects driving your envy?

How can you move out of the limited point of view of envy, and step into a place of shared success and collaboration with your friends, peers, and colleagues?

What can you do — specifically, right now — to move yourself closer to the objects of your envy?

Answer these questions, and you’ll find yourself creating an instant roadmap for yourself. This is how you sublimate envy into action, how you convert it into fuel and motivation.

If we can do that — if we learn to understand and use envy as a teacher — then that abyss narrows and eventually disappears, and we become closer to the people in our lives who have what we want. They go from rivals to friends, competitors to models, objects of envy to sources of inspiration.

Or, as Dante put it,

For there, the more who say, “This joy is ours,”

the more joy is possessed by every soul,

the more that cloister burns in charity.

The journey through envy is the shift from “this joy is mine” to “this joy is ours.” But the way through envy is to embrace it first, study it, and find out where it wants to take us.

Deeper into ourselves, and further into our journeys — driven, rather than paralyzed, by the complicated teacher we call envy.

[Featured photo by Raúl González]