Alex Kouts (@akouts) is a teacher, adventure technologist, Chief Product Officer of Countable, and — as you’ll soon discover — quite savvy in negotiation. This is part one of a three-part series. Make sure to check out parts two and three!

What We Discuss with Alex Kouts:

- How to negotiate for anything — from your salary to a new mattress.

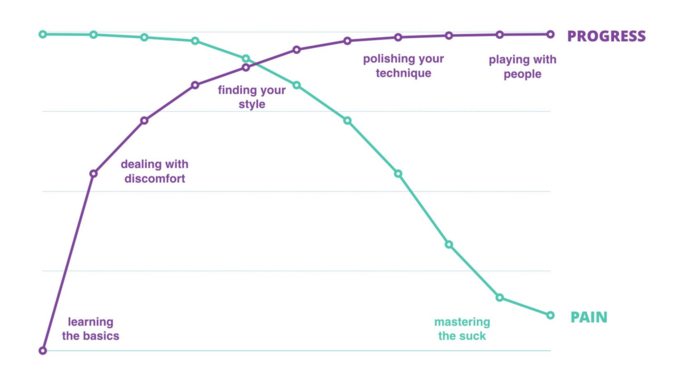

- How the relation between progress and pain works.

- Why no talent + hard work will always beat talent + no work.

- Is Google stalking to prepare for an interview or negotiation a good thing?

- How many “no” answers can you get in five days — and what could this possibly teach you about negotiation?

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

Like salesmanship, negotiation is a valuable skill that many hesitate to master because of unfairly attached negative qualities that have come to be associated with it. Some think of it as the dark arts for persuading others to do one’s bidding against their own self-interests, but done properly, it results in wins for both sides of the table.

Business developer, startup veteran, Countable CPO, and professional negotiator Alex Kouts joins us for this first episode of a multi-part series to share his expert secrets of negotiation with those of us who feel a little squeamish at the prospect of getting a “yes” in a world that actually finds it surprisingly hard to say “no.” Listen, learn, and enjoy!

This is part one of a three-part series. Make sure to check out parts two and three!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

More About This Show

A lot of classes that profess to teach successful negotiation are terrible. More often than not, they’re taught by some guy who read a book that was written in the ’20s, chock full of well-meaning but fairly useless advice like “look them in the eye!” or “Never make the first offer!” or “Make sure you have a firm handshake!”

This is one of the reasons that Alex Kouts doesn’t believe in teaching negotiation with books.

“Everybody always asks me when I teach these classes what books I would recommend for negotiation,” says Alex. “I almost never recommend books — primarily because negotiation is such a human experience. But ideally today what we’re going to walk through are things that you can walk away and try today in something that you’re doing as opposed to the ‘deep theory’ of negotiation. While that stuff can be really interesting and a great basis for learning how to do this stuff better, it’s not ultimately as useful.”

Win/Win Negotiation with Empathy

A lot of people go into negotiations thinking they have to be pushy or play games — like purposely being late to meetings — in order to assert their dominance and play from a place of perceived power. Such tactics might work to a limited degree, but Alex believes they come from a misguided perspective.

“On a point-to-point basis or individual case, if you walk in and [think], ‘I’m going to kill! I’m going to win! I’m going to intimidate the other side! I’m going to get all the things I want!'” says Alex. “You can do it decently because you’re able to get over that first hurdle — being able to ask for things because you’ve already decided you’re going to — that’s really the only benefit you get from that mindset in my opinion.

“Negotiations, when done correctly, are an incredibly empathetic, mutual conversation that happens. It’s negotiation of two sides with individualistic interests that I’m trying to bring together in a way that feels constructive for everybody. It is not me going in and ‘winning’ or me going in and intimidating you or screwing you over.”

Or as Never Split the Difference author Chris Voss would say, “Negotiations are about the use of tactical empathy.”

The Pain/Progress Chart

As you start to learn a skill, you’re going to endure a lot of pain — but you’re also going to make rapid strides in progress because you’re starting from zero. At the point when your levels of progress and pain intersect, you’ll enter the point of true mastery (playing the piano, understanding the role of the DH in baseball, speaking Serbian, etc.) where progress slows and plateaus — but you’ll suffer less and less for it. To get to that point, you’ll pay your dues; how much pain are you willing to eat?

“If you’re learning negotiations today,” says Alex, “if you kind of embark on your journey getting better at this stuff…as fast as you will ever get because you’re learning the basics and you’re beginning to deal with discomfort. Eventually if you keep going that curve begins to flatten off as it reaches the top; you’re finding your style; you’re polishing your technique.

“Another way that Ira Glass put this was that at the beginning of learning any skill, there’s where your taste is, which is really high up. And where your actual physical ability to execute is really low. And the distance between those two things is just pure pain! That’s what it is learning anything. Negotiation is the same. At the beginning you’re progressing really fast, but your pain is as high as it will ever be. Over time as you do things more, your pain will level out. It will go down, and it…will never quite hit the zero axis, never quite go away, because no matter how much you do stuff — with negotiations — you’re always testing the social fabric when you ask for things that you want.

“But the point here is that the pain will never go away. So if you want to get good at something, you need to internalize it. You have to embrace the suck!”

Listen to this show in its entirety to learn more about how negotiation figures into the social contract, how the Rudy Chart illustrates that no talent paired with hard work will always beat talent paired with no work, how the conflict averse can start to overcome their fear of negotiation and learn to ask for what they want, the difference just one salary negotiation over the course of a long career at one company can make, the pros and cons of rationalization, what the first offer always means (and Alex’s secret sauce for dealing with it), the importance of empathy in negotiation, the power of preparation before going into a negotiation, what a BATNA is and how it can help you understand your options, how social cost is exploited in negotiations and what we can do to defend against it, how information asymmetry works, the power of no, and lots more.

THANKS, ALEX KOUTS!

If you enjoyed this session with Alex Kouts, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Alex Kouts at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Alex’s Pre-Negotiation Worksheet

- Alex’s Mastering Negotiations Workshop

- Alex at Twitter

- Countable

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It by Chris Voss and Tahl Raz

- The Taste Gap: Ira Glass on the Secret of Creative Success, Animated in Living Typography by Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

- Social Contract Theory, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- TJHS 28: James Fallon | How to Spot a Psychopath

- Muggsy Bogues

- Rudy

- What is Information Asymmetry? The Economist

Transcript for Alex Kouts | The Secrets You Don’t Know About Negotiation Part One (Episode 70)

Jordan Harbinger: [00:00:00] Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. As always, I'm here with my producer, Jason DeFillippo. Today, we're talking with my good friend, Alex Kouts. If you've been around for a while with us you know he is one of the smartest people that at least that I know. Probably one of the smartest people that you know through the show as well. He has a varied background in many startups working with a lot of people that we’ve, I’ve all heard of. I'll spare you that though. Today, we're talking about negotiation. This is the beginning of a masterclass on negotiation. It's going to be a three -- at least three-part series. This is part one.

[00:00:34] Alex has been teaching negotiation for years and this isn't just one of those, make sure you let them do the first offer. So you know there's advanced stuff in here, that is stuff that you haven't thought of, that you haven't read in negotiation books that's used regularly in high-level VCs, Silicon Valley, corporate negotiations, government offices. This is where Alex teaches this stuff. So this isn't just some sort of academic negotiation knowledge. This is on the ground practical stuff. You'll learn anything from how to negotiate your salary to, well, how to negotiate for a freaking mattress is one of the examples that we used. He's done a lot of thinking and a lot of teaching when it comes to negotiation, so if you're even remotely interested in this topic, or you already think you know it all, I highly recommend this episode or this set of episodes for you. Of course, we have a worksheet for today's episode and we will have them for all of these episodes here, so you can make sure you solidify your understanding of all the key takeaways and negotiation tactics from Alex Kouts. That link is in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast.

[00:01:39] By the way, I've been teaching networking. It's been the number one lever in my life for personal and professional. When we had to rebuild the business, my network was there. It's the reason we're back at over five million downloads a month. It's a reason we were picked as Apple's Best of 2018. It's the team, it's the network, it's the people around you, and I created a free course to teach you how to consistently engage and reach out to people in your personal and professional network. It's free. I just, look, this is not one of those things where it's like entering your credit card number. This is free. I want it to change your life. That’s the whole point and it's called Six Minute Networking. If you were in the old one LevelOne, it replaces that. It's new and improved. Six Minute Networking, and it's at jordanharbinger.com/course. That's jordanharbinger.com/course. See you in there.

[00:02:27] Now here's Alex Kouts. You're going to teach us some negotiation.

Alex Kouts: [00:02:30] Yeah.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:02:31] So what qualifies you to teach us some negotiation? I mean you're a negotiation teacher, but aside from that, aside from that triviality.

Alex Kouts: [00:02:39] Yeah, this was funny. I've built my career kind of building and scaling tech startups in the Bay Area here. And one of the really nice things about working at a startup is that you end up having to do a lot of different things very quickly under in extreme emotional duress, let's put it that way. So I got into a place where I was basically building businesses through business development, so large contract negotiation.

[00:02:59] So a big part of what I did for the beginning of my career was pretty much negotiation focused, and through that develop just a different outlook on it than a lot of the folks that I was working with. And that worked out really well for the companies that I was kind of leading and working with. And then I got asked by other companies to come in and help them negotiate things and develop this like significant sample set of just all these different scenarios and negotiation. And then I started teaching it. And the cool thing about teaching, the reason that I teach really is that I get to learn from other people's stories about negotiation. And one of the best ways to kind of sharpen your skill set if you're a practitioner is to have to teach things to other people. So a lot of what I've learned to is a compendium of not only my own experience, kind of extensively in my own career, but you know, other people's experiences, sharing their stories, helping them work through their issues. So it's quite a decent a scope at this point.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:03:43] All right, so what are we going to walk away with here is not just, it doesn't sound like it's just going to be this academic study of negotiation. Because I remember when I went to law school, they taught us some negotiation tactics and it was like all, “All right, always start the first offer because anchoring,” and everyone's like, “Whoa, this is really important.” And then after that, it kind of got even worse and it was more like, you know, always go in there and be on time and just sit at the one under the table --

Alex Kouts: [00:04:09] Shake their hand and look them in the eye.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:04:10] Look them in the eye, firm handshake.

Alex Kouts: [00:04:12] Wear a power tie.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:04:13] Things like don't drink too much water because if you leave to go to the bathroom, it looks like a weakness. And I'm like, this is a person who read a book once on negotiation that was written in 1924.

Alex Kouts: [00:04:23] Right. Yeah. The Donald Trump part of making the deal. Yeah. It's funny, everybody always asked me when I teach these classes what books I would recommend for negotiation, but I almost never recommend books. Primarily because negotiation is such a human experience. But ideally, today what we're going to walk through were things that you can walk away and try today in something that you're doing, as opposed to the deep theory of negotiation. While that stuff can be really interesting and a great basis for learning how to do this stuff better, it's not ultimately as useful. So the way that I teach this course is that I want people to walk away with very tactical things that they can say. So turns of phrase a specific, you know, visual or physical cues, things you can just say in a negotiation. So it's not, again, we're divorcing it a little bit from the theory, although that's a very useful way to look in negotiations is it provides a good baseline for understanding some of the things that even you're doing on your own. We want this to be super tactical, so do this, don't do this, do this, don't do this.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:05:15] That's what we like here, practicals, takeaways, things people can use and stuff that actually works based on experience instead of just a theory that someone thought of. I know that you've probably seen this, it’s a little tangent here, but there was a tweet by, I think it was already Paul and I can't remember exactly where he worked, some VC fund, and he said he'd overheard some other VCs saying things like, we're deliberately going to be 30 to 60 minutes late for every meeting because it's signals importance and power. And he had tweeted this and he's like, what is happening with you people? This is ridiculous. And people were in the comments, of course, being like, “I know tons of people that do this,” or “Oh this is everything that's wrong with VC today.”

Alex Kouts: [00:06:00] It is. I mean that kind of stuff. We're like transparent power place, in my opinion, a relic of looking at negotiations incorrectly. People look at them as like, it's a zero-sum game, win versus lose, that kind of thing. But in reality that leads to bad outcomes stretched out over a series of negotiations I think, you know, in a point to point basis or an individual case, if you walk in and you're like, I'm going to kill, I'm going to win. I'm going to let him intimidate the other side. I'm going to get all the things I want. You can do decently because you're able to get over that first hurdle, which we'll talk about later of just being able to ask for things, because you've already decided you're going to. But that's really the only benefit you get from that mindset in my opinion.

[00:06:34] Negotiations when done correctly are an incredibly empathetic mutual conversation that happens. And it's a negotiation of two sides with individualistic interests that I'm trying to bring together in a way that feels constructive for everybody. It is not me going in and winning or me going in and intimidating you or screwing you over.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:06:51] Gotcha. Okay. And I think that's important and that's a really good fit for the things that we teach on the Jordan Harbinger Show and add Advanced Human Dynamics. Because we don't want to leave people thinking this is a terrible experience, doing business with them is awful. I'm just glad it's over.

Alex Kouts: [00:07:05] Yeah.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:07:06] Right. We want people to think, “Okay, well, we negotiated this and I'm happy to be moving forward,” not “Wow, that burns, and I can't wait until this thing has expired.”

Alex Kouts: [00:07:15] Yeah. Thank God that I'll never see these people again.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:07:17] Right.

Alex Kouts: [00:07:17] Yeah. So the Webster's definition of negotiations, it's a mutual discussion, an arrangement of terms of a transaction or agreement, which sounds like a really simple but no sense.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:07:26] That’s really sexy and romantic.

Alex Kouts: [00:07:27] It is. That's the sexiest part of the class, still downhill from here. But in reality, if you unpack that a little bit, it's a mutual discussion and arrangement of terms of a transaction. It's not m, going in and getting what I want. It's not me, just advocating for my own self-interests. It's me, learning about the other side, and actually one of the only books that I recommend on negotiations is called Never Split the Difference by Chris Voss.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:07:48] Chris Voss. Yeah.

Alex Kouts: [00:07:49] Has he been on your show?

Jordan Harbinger: [00:07:50] He has, yeah.

Alex Kouts: [00:07:51] It's a great, great, a great book. And to be honest, I've only read about 60 percent of it, but that's what I do with every book, so that's not specifically this one.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:07:57] Well, hopefully you just skipped the beginning because it was really good.

Alex Kouts: [00:07:59] But yeah, I mean he uses a phrase called tactical empathy. And I've been teaching this class for years and years saying basically the same thing in different words. But I like the way he phrases it. Negotiations are about the use of tactical empathy.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:08:10] Okay. So tactical empathy, being empathy deployed in some way that's strategic towards the outcome of the negotiation.

Alex Kouts: [00:08:16] Exactly.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:08:17] Okay.

Alex Kouts: [00:08:18] That's exactly right.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:08:18] I can hang with that.

Alex Kouts: [00:08:19] So one of the things that I throw up at the beginning of my class is this kind of chart, and obviously not everyone can see it or although we can put on the West Side afterwards.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:08:25] This chart that you don't see right now.

Alex Kouts: [00:08:28] So close your eyes. No. So in this chart, there's basically two inverse curves. It's a pain and a progress curve. And I throw this up at the beginning of negotiation class. Although if I was teaching intro to piano or trumpet, I would use the same chart because it's the same basic concept, is that when you're learning a new skill of any kind, whether again, it's a musical instrument or a sport or negotiation, at the beginning, your progress is as fast feeling as it will ever feel. Primarily because you're starting from zero. Like in Silicon Valley, it's very famous you know, startups will go and say like, “Well we had 10,000 percent revenue growth last month,” and I was like, “Great! Well you had 1 dollar in revenue the month before and now you have 10,000 dollar revenue.” So it's not really, it's a false view of things, but the reality is that proportionately at the beginning it feels like you're growing as fast as you ever are. And that's the benefit.

[00:09:12] So if you're learning negotiations today, if you kind of embark on your journey of getting better at this stuff, maybe you've already started on this, you are getting better as fast as you will ever get because you're learning the basics and you're beginning to deal with this comfort. And then eventually if you keep going and that curve begins to flatten off as it reaches the top, you're finding your style, you’re polishing your technique, and eventually, if you stick with it long enough, you're just playing with people. That's what I do now.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:09:35] Okay. Is that a good thing? It sounds kind of like it could go either way.

Alex Kouts: [00:09:39] Yeah, you just get bored. It's the same thing I think, you know, really, really good soccer players for instance, they're really good at doing trick stuff because they're bored and they're just kicking around to see how far they can take their skills. But I'll just say things in negotiations to destabilize people sometimes just to see how they react. Primarily just because I'm bored and I've done this a lot.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:09:55] Can you give us an example of something that destabilizes or is that something we're getting into later?

Alex Kouts: [00:09:59] Yeah, you know, it's interesting, this is going to sound slightly rough, but sometimes I do it in job offers scenarios. So somebody negotiates with me. Let's say I'm offering someone a job and they come back with a counter. I may say something savvy, destabilizing like, “Really, you think you're worth that? Interesting.” And I'll immediately back off that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:10:18] Zing, yeah.

Alex Kouts: [00:10:19] I just want to see who I'm dealing with.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:10:20] Right, okay.

Alex Kouts: [00:10:21] Now I don't mean that to be mean, and I'll kind of, I'll make nice afterwards. But seeing people's emotional reaction to something can also tell me how deeply engaged they are married to that idea versus like if they're fishing for something else, sometimes I'll just throw a little grenade in the water and test people.

[00:10:36] Now so back to the curve. So at the top, there's this progress curve that again grows and then flattens off over time. Again at the beginning, I'm getting as good as I will ever get proportionally as fast as I will ever be at negotiations. Now on the inverse is the pain curve. When I start learning anything, pain is at an all-time high because I've never done it before. If I'm learning to play trumpet for the first time, it sounds like ass people are telling me to go practice in the forest somewhere, get out of my house, that kind of thing. The pain is enormously high because it sounds terrible. And another way that I believe Ira Glass put this, was that at the beginning of learning any skill, there's where your taste is, which is really high up. And where your actual physical ability to execute is really low. And the distance between those two things is just pure pain!

Jordan Harbinger: [00:11:16] Right. Right.

Alex Kouts: [00:11:17] That's what it is learning anything. Negotiations, it's the same. So at the beginning, you’re progressing really fast, but your pain is as high as it will ever be. Now over time as you do things more, your pain will level out. It will go down, your pain level and it will begin to level out, and never quite hit the zero axis, never quite go away, because no matter how much you do stuff with negotiations you’re always testing the social fabric when you ask for things that you want, which we’ll get back to later. But the point here is that the pain will never go away. So if you want to get good at something, you need to internalize the idea that you have to embrace the suck. And it's the same with negotiations. It will be painful at the beginning as you're trying to get good at this stuff, but you'll be progressing really quickly. You just got to stick with it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:11:55] That's good to know. Because I think a lot of people, negotiation and sales kind of dovetail nicely where people go, well, I don't want to seem salesy. There's no such word as negotiation-y, but it does apply. People don't want to negotiate their salary or for that matter, anything. They don't want to barter or bargain with a cab driver at a restaurant or something like that where they feel they're actually being rip, they know they're being ripped off, and they won't say anything. Well, I don't know, it's, you know, I don't want to make waves, or they don't even say that. They just know that the conflict is so uncomfortable that they won't do it. And that's the reason I think that a lot of people bring a friend with them when they're negotiating to buy a car, and I've done that for mostly female friends and we'll get into that in a little bit. Where I'll go to the dealership and she just knows, “Look, when I come here alone, they just try to pull the wool over my eyes because they think I'm a dumb gal. But also she doesn't want to say this is too much.” She knows that I can do it because I'm a jackass and that's why we're friends, right? She phrases it more nicely, of course, like, “Well, you're a lawyer, you're used to this.” But the translation really is that I'm not afraid to do this, but this was a learned skill. I didn't grow up as a kid going, I can't wait to get into an adversarial relationship with somebody potentially at a car dealership.

Alex Kouts: [00:13:14] You've keyed into something really important. And that's one of the fundamentals which we'll talk about more in a moment, but it comes back to social costs and what you're talking about there is you are very, all of us are very implicitly aware of the social contract. When we are engaging with other people in a value exchange, we're very aware of their needs and wants. We're aware of ours, even if we're not aware of that, we're aware of their needs, we are. It just preprogrammed in us living in a modern society, and so it makes it very difficult for us to advocate for our own self-interest because we have trouble putting those interests at least at par with other people's interests. And there's a lot of ways you can combat that, which we'll talk about.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:13:49] When you say the social contract, can you define that just in one or two sentences? Because I think a lot of people might go, “Oh yeah, wait, what is that?”

Alex Kouts: [00:13:57] Yeah. Yeah. So society largely is a compendium of rules and customs that are designed to effectively pre-doc protect social order. And so the social contract to find, if you Google the word is it's an implicit agreement among the members of a society to cooperate for social benefits. An example, by sacrificing some individual freedoms for that protection of living in a society. So put in plain speak. Basically what that means is that I'm willing to sacrifice some of my own needs for the greater good because the greater good pays back to me in dividends.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:14:28] Okay. So we don't want to just be totally individualistic in some points. And so this is hard-coded into us, would you say?

Alex Kouts: [00:14:36] Oh yeah, for sure. I mean, the social contract is hardcoded into us from birth effectively. Now, some of us deal with that better ways than others. And one of the phrases does your right now for behavioral psychologists is this trade called agreeableness. How agreeable are you as a person? If you're very agreeable, you tend to put your needs below other people's needs. You tend to be more equilibrium focused. I just want to keep things on an even keel. If you are less agreeable, you're more comfortable advocating for your own self-interest. It's not as painful to you to kind of test and twist that social fabric for your own purposes. Now, taken to an extreme is like a sociopath who completely doesn't give a damn about twisting or breaking or violating that social fabric really openly and painfully.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:17] That makes sense. Yeah. We study a lot of psychopaths and sociopaths on the show.

Alex Kouts: [00:15:22] On the show.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:23] And whenever people give examples of, well, this is hard-coded, I'm thinking, well, there's going to be some people who actually see that that's hard-coded and just take advantage of it, but it is --

Alex Kouts: [00:15:31] Absolutely.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:32] Rare.

Alex Kouts: [00:15:32] Yeah.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:33] This is a learned skill, right? So I think a lot of people think, “Oh well I'm not good at this naturally.” I'm not naturally good at this because maybe they're conflict-averse.

Alex Kouts: [00:15:41] Yeah, I hear that all the time and it absolutely kills me. When teaching negotiations, I'll often have people come to the class and say, “Well, I'm just not good at talking,” or “I just get really nervous in negotiating scenarios and it's just who I am as a person, and I'm trying to just get a little bit better, but I know I'm always going to be terrible at it.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:56] Oh, that sucks.

Alex Kouts: [00:15:56] It kills me. It's a defeatist attitude, and I understand where that comes from. For sure. We're all insecure about the areas where we think we need to improve. But one of the things that I walked through in my classes is something that I call the Rudy curve or the Rudy pyramid. Now, at the bottom of the pyramid, the pyramid basically tells us how effective or how good people are at a particular skill. At the bottom of the pyramid, meaning people who were the worst at something are people who have no inherent talent. Maybe they're not born with that particular skill or who they are as a person that's kind of counter to doing that thing well, and they're lazy. So these are people who don't have, again, don't naturally have that imbued kind of blessed skill. They're not an amazing soccer player to begin with, but they're incredibly lazy and they don't work hard. These are people who are as shitty as anyone could possibly be at whatever they're trying to do.

[00:16:43] Now, leaps and bounds above that kind of in the pyramid or people who may have natural imbued talent. Maybe they're born to do this, they're naturally good athletes or something like that, but they're lazy as well, so they don't work hard. So really like those people are above people who have no talent or lazy, but actually not that far. Now, above that are people that have no talent and are hardworking. Now, professional sports are filled with people who weren't necessarily given athletic gifts, maybe weren't super tall or super-fast or super strong, lots of muscle, but they worked their asses off. And you see this constantly. Look at Muggsy Bogues famous point guard in the NBA, tiny guy. He's like 2 foot 5, but he was an absolute monster on the court because he worked harder than almost anybody.

[00:17:23] And this is what I call the Rudy level. This was, if you’ve seen the movie Rudy, this tiny little guy, his dream was to play in the Notre Dame football team and he kept getting the shit kicked out of him in practices and tryouts and never made it. And eventually just worked so hard, he got onto the team and kind of fulfilled his dreams to be--

Jordan Harbinger: [00:17:38] While everyone was chanting.

Alex Kouts: [00:17:39] Exactly, Rudy, Rudy. It was absolutely beautiful moment. If you don't cry up that God help you. But above that are the people who have talent and work their asses off. These are the Cristiano Ronaldo, the Michael Jordans, the LeBron James. These are people that you almost never meet. There are one in millions and millions, and if you do meet them, God help you.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:17:57] You're embarrassing me. You're embarrassing me.

Alex Kouts: [00:17:58] I know.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:17:58] But continue, continue.

Alex Kouts: [00:17:59] You're uncomfortable with the word hero.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:18:01] Yes, yes.

Alex Kouts: [00:18:01] I got it. No, but it's true. I mean you rarely ever meet people like this. So the point of this curve is again at the bottom or people that have no talent and are lazy, a little bit above that or people who have talent and are lazy, leaps and bounds above that or people that may not have that natural talent that worked their ass off. And then the top of the pyramid is people that have that talent and work their ass off. So the message here is that hard work beats talent when talent doesn't work hard every single time.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:18:24] So hopefully everyone listening to this is somewhere between the talent and hard work, top of the pyramid, if that's you, congratulations. Or the no-talent, hard work level or possibly the talent plus lazy, but then actually trying to get a taste of the work ethic. If you're at the bottom, you probably don't listen to this show because it's probably boring and you're looking for something that you can listen to while you play video games.

Alex Kouts: [00:18:46] I mean, your show focuses on skill developments. The fact that someone's listening to this show in the first place is like a positive step in that direction that they want to develop in some meaningful way. So yeah, I would say you know, most of the people that we're talking about here probably in the middle two tiers.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:18:57] Yeah, that makes sense. All right, so everyone's terrified of negotiation. We've kind of covered that. All right, what else?

Alex Kouts: [00:19:05] Yes. So when you start a negotiation, so when I talk about the fundamentals of how to get good at this stuff, so now we've done the intro. Let’s go to the fundamentals, is that your first problem will be your perspective. That's true with everybody. And as you mentioned just a second ago, everybody is terrified of negotiations. When we are twisting that social fabric, it creates pain for us.

So for most of us, the hardest part is asking, we just can't get to the point where we do. A very large percentage of the pay gap between men and women in the workforce is defined by the fact that women very infrequently negotiate relative to men. I think it's women are about 60 percent as likely to negotiate for a job offer as a man is. And that's really, really unfortunate. It's one of the areas that I worked very closely with my students on is getting over this part of rationalizing and being comfortable making an ask. And so in order to do that, you have to recognize why those things happen. Why is it hard for us to ask the things we want? Well, the first part is we don't know what we're missing.

[00:20:00] So one of the examples that I pull up in front of my students in class is I pull up Excel, and I basically run through three different scenarios. Let's say there's three people, Andrew, Betsy, and Charlie. They all graduated from the same college with the same degree and go into the same job immediately afterwards. They are the same in every single way. The gender difference here is just to make things sound equal. Let's say that that's immaterial for here.

[00:20:22] Now each one of them gets the average exiting salary for someone coming out of college right now is around 47, 48k. But let's just run up to 50 for easy sake. So each of the three of them gets off for the same job for 50,000 dollars out of college. Now, Andrew doesn't negotiate his job, gets 50k, takes 50k, that's a salary he starts. Now, Betsy negotiates her job and does pretty decent. She gets somewhere in the neighborhood of 12 percent, which is a pretty normal case for someone who negotiates a job offer scenario. So she walks away with 56k. And then Charlie does the same thing. Charlie negotiates that job as well, and he gets 56k. So now let's say over the course of your career, you're going to be working somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 or 42 years. That seems to be the average. You're going to retire when you're 65.

[00:21:07] So for each one of these, the first salary that I start out as my starting place, right? That's where all the salaries, everything that I do for the rest of my career starts in that one first place. So for Andrew who didn't negotiate, it all gets 50k. Let's just say over the course of his career, 42 years working, he gets an average three percent a year cost of living adjustment. So over the course of his career, he's going to make somewhere in the neighborhood of four million dollars. That's his total career earnings. If he adjusts that salary up every year. Now for Betsy, who negotiated a first job offer and got 56k, she only negotiated that one offer that one time in her entire career. So she started 56k, Andrew started 50, they both get the cost of living adjustment every year. So for Betsy, just because she negotiated that one time over the course of her career, she will make about 500,000 dollars more in her life than Charlie will. That's the benefit of that compounded effect of that one negotiation one time. That's it.

[00:22:03] Now, let's look at Charlie, the third one. So Andrew never negotiates. Betsy negotiates once and does 500k better in her career. Charlie is now going to negotiate every single time he switches jobs. Now, let's say on average person switches jobs every seven years, and every single time Charlie switches jobs, he's going to negotiate for better. And let's say he has the same outcome he did the first time a 12 percent increase. So if he's negotiating his job that one, two, three, four, five times over the course of his career, every seven years or so, he's going to make 1.985 million dollars more than Andrew did.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:22:36] So someone's entire retirement.

Alex Kouts: [00:22:39] Yeah.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:22:39] Healthy retirement, two million bucks and well maybe, maybe that's not healthy in 42 years, but for now that would be quite healthy.

Alex Kouts: [00:22:46] And if you put that in an interest-bearing savings account, I mean that's going to be significantly more and can definitely fund your retirement. But the point here is that most people are not aware of the downstream effects of not negotiating for things. They don't think about the consequences of not having negotiated that salary one forever. Now, a lot of people in my class feel super bad about this. When I mentioned it, because it's like, “Oh shit, I didn't negotiate.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:23:06] Because they’re 40.

Alex Kouts: [00:23:07] Exactly.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:23:07] They’re pushing 40 like me at 38, and they've gone, “Oh man.”

Alex Kouts: [00:23:11] It's like, “I didn't give a shit at my first job.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:23:11] “I should have half a million more dollars by now.”

Alex Kouts: [00:23:13] Exactly. But the point is that when you make these decisions or they're made for you, the compounding effects of those things are significant. You don't see them. They're insidious and they're really, really bad. So sometimes when we get into negotiations and we're trying to get ready to do them, I talk about the power of rationalization, you need to rationalize your way into negotiating. This is one way to power your rationalization. Well, if I don't negotiate here, what does that mean for me if I don't do this kind of thing later on, what could I do with that money had I negotiated the first time? So that's one.

[00:23:45] Let's talk about rationalization for a second.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:23:47] Sure.

Alex Kouts: [00:23:48] Rationalization is both one of the best tools that humanity has ever invented and one of our worst enemies. It can get us over the hump negotiating and we'll talk about how to do that in a second. It can also help us rationalize doing terrible things.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:24:00] Rationalization is why I had pizza last night at 9 p.m. for dinner. Instead of just going to bed hungry.

Alex Kouts: [00:24:05] Because you worked out, you're like, now I can eat this entire cake.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:24:07] Yeah, kind of something like that.

Alex Kouts: [00:24:09] Yeah. Moral licensing. It's a very common thing that you run into in behavioral psychology.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:24:14] It's even worse when you know you're doing it in the moment and you just don't care as it as the deliciousness slides down.

Alex Kouts: [00:24:21] That makes it a lot easier.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:24:22] Yeah. It's a problem though, and if you don't know what's happening, it's your worst enemy. It will dictate essentially your whole life.

Alex Kouts: [00:24:28] Yeah. I mean the entire national socialist movement in Germany, the Nazi movement was an entire country, or a very large number of people rationalizing very difficult and insane things in some cases because they felt as though they had gotten a really raw deal from World War One. And there were all kinds of things culturally happening inside the country that made it easy for people to rationalize to us today unimaginable things. But that happens to us every day in our lives. Like I worked out a little bit, I'm going to eat this cake, right? But if that can be used for our benefit in negotiations, so one of the ways that we can rationalize being more comfortable asking for things is the foregone revenue conclusion. Like we talked about a moment ago. The one that I use personally, and this is kind of my secret sauce for negotiations, is that whenever I get an offer, at every first offer that comes maybe for a job offer negotiation, a price for a vendor contract I'm negotiating is a fuck you price. That is somebody who is priced me, and they're giving me a number for what they think they can get me for what they think I think I'm worth. So they’re pricing me and that irritates me.

[00:25:27] So I walked through the negotiation. I walk into it with a sense that I have to defend myself against this imposition from somebody else. It makes it very easy for me to rationalize asking for the things I want. It makes it very difficult for me not to do that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:25:39] So you're kind of getting fired up a little bit.

Alex Kouts: [00:25:41] Exactly.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:25:41] Yeah. Okay.

Alex Kouts: [00:25:42] I'm getting a little pissed off. Now that's dangerous and it doesn't work for everybody because sometimes we can go too far with that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:25:49] Yeah, you’re on tilt.

Alex Kouts: [00:25:48] We could feel like, exactly. The other person is screwing me over. Who do you think you are? And then that can come through and inflection and word choice and don't do that. That's bad. You don't want to come out pissed off swinging, which does happen.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:25:58] You see, I mean Mike Tyson, you know he would get fired up before a fight. You turn it up to 11 and a half instead of 11, you eat someone's ear.

Alex Kouts: [00:26:06] Yeah. Exactly. Yeah. No, no eating of your eating of ears.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:08] No eating of ears. Really bad negotiation tactic especially.

Alex Kouts: [00:26:12] That's a good rule of thumb. So another one is, you know, so one foregone conclusion or foregone revenue. The second is the fuck you price. And the third often one is emulation. So just think of somebody that you respect like Beyonce, right? Let's just say Beyonce, Queen B, right?

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:26] Absolutely.

Alex Kouts: [00:26:27] Would Beyonce negotiate for what she wants? Would Beyonce take the first offer? What would she do? It could be an athlete, it could be a business person you respect. It could be your parents, your boss, somebody around you that you know, again, would advocate for their own self-interest.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:39] Charlie Sheen would negotiate this.

Alex Kouts: [00:26:41] That’s right. Charlie Sheen would destroy the situation.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:43] Yeah, he would. I'm sure you're right about that.

Alex Kouts: [00:26:47] Just a coke-fueled negotiation rampage.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:49] Exactly.

Alex Kouts: [00:26:50] Exactly. So yeah, that first part there is again, using and leveraging the power of rationalization to get over that hump of asking for what you want. That's so huge.

[00:26:59] The next one, that I talk about a lot in the class is the role of empathy. Really when you're teaching negotiations, it's effectively a class in empathy. And like we talked about before, tactical empathy, the importance of that cannot be overstated. Good negotiators, great negotiators are intensely empathetic. They not only understand the other side, but they understand how they're evaluated, what their wins and what their losses look like, what their goals, their hopes and dreams, their worst nightmares look like. All of these things are tools in your tool belt to effectively negotiate and some use it for good. Some use it for naughtiness. If you take empathy too far, it becomes blackmail. I know exactly where your pressure points are, so I'm going to push on them. I'm going to make you feel really insecure. That's obviously taking it too far, but that's really tactical empathy.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:27:42] That's funny. You never really think of empathy as being negative at all. It's only really used in the sense of he's still empathetic. He really understands people and feels their pain and understands them and is kind, it's really never used for, “Wow. He's so empathetic that he took advantage of everybody's weaknesses.”

Alex Kouts: [00:27:59] Just blackmailed the hell out of everybody.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:28:00] Yeah. Again, going back to psychopathy. Psychopaths don't necessarily have a lack of empathy. In many ways, they can use that to their advantage. They just have a lack of morality in some cases going back to James Fallon.

Alex Kouts: [00:28:13] Complete lack of sympathy. Yeah, absolutely.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:28:14] Yes, exactly.

Alex Kouts: [00:28:16] Yeah, so that's huge. So we're going to keep coming back to that theme over the course of this conversation because it's so, so important. It's the thread that ties everything together. The next thing and one of the most important parts of negotiations as well, and we'll talk about this more directed a little bit later, is the power of pre-work. So you need to internalize the idea that the better-prepared person almost always wins in a negotiation. I negotiate for a living. I've been teaching this stuff for years. But if I'm going up against somebody who knows all the inputs and outputs of the situation and has really done their homework and I haven't done any of it, I am at a significant disadvantage no matter how comfortable I am doing it in the first place. So that's huge.

[00:28:55] So in a negotiation, we actually walked through in the pre-work side of things, there's actually a worksheet which we'll put up on the site that everyone can take a look at, the walks through all the things that you need to know walking into a negotiation. So effectively, I had my students kind of print this worksheet out, but it runs through a couple different things.

[00:29:11] Number one, what am I negotiating? That's the basic stuff. What's the timeline in which I need to make a deal by? Do I need to give this job offer and answer by the end of the week? Because then that changes my decision criteria, how I'm going to do things. Then it goes through the party involved and these are the most important things in the worksheet. This is where we stalk people on Google. This is where we learn as much about we as we can about who they are and what they want. What does that person do that I'm negotiating with? Let's say it's a business to business contract. Who does that person report in to you? How are they evaluated? How do they get their bonus? What is the boss looking for? Who are they going to have to sell this to other folks?

[00:29:45] When I meet people in a business scenario, I ask two questions always. One is, what does a win look like for you? Where are you driving towards what's important to you? And the second is, what keeps you up at night? What's your worst nightmare? And I've built a couple of digital consultancies over the years. And ironically, whenever I ask clients or prospective clients that question, just a side note, it's a lot easier to sell them on taking the pain away than it is giving them what they want. Even if I could devise a strategy or give them the service that would make all their goals come true or goals get achieved, they tend to not believe it, but they're much more likely to believe that I can make the pain stop. So often when consultants sell clients, they're selling them on making pain stop, which is really interesting.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:30:26] That is interesting. I think we know that though from general humanity, right? That we will go through lengths to avoid pain rather than seeking pleasure, or doing something right. We’ll choose short term pain avoidance in almost every case.

Alex Kouts: [00:30:41] Yeah, absolutely. So anyway, the parties involved, that's really, really important. And another thing that we want to make sure we understand about them in the same worksheet is what their BATNA is. Now, BATNA is an acronym that you pretty much only hear in negotiation conversations, but it stands for Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement. So that means that if they don't do a deal with me, they're going to do a deal with someone else. I need to know who those people are. For instance, if they are going to buy something from me. They don't buy from me. They'll buy from these four competitors. So understanding who I'm compared to again, helps me pitch against those things, helps me create a differentiation for what I'm offering relative to what their other options are.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:16] Yeah, that’s good. I do that sometimes, or I have done that in the past when selling corporate training programs and going, “Oh, well, who else are you looking at?” Sometimes it's as simple as asking ,and oftentimes the person will say, “No one,” we're either going to get this from you or we're not going to get it at all. Or they'll say, “Well, we're looking at you and we're also looking at this Dale Carnegie course,” and it's like, “Oh, okay.” I can probably disassemble anything that they have taught there by having taken that course myself and then kind of picking out why it would be the absolute wrong decision for everything that you guys are looking for. Yeah.

Alex Kouts: [00:31:48] Yeah. Oh, these guys, here's five reasons why they suck.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:50] Right.

Alex Kouts: [00:31:50] Exactly.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:51] Or they're decent. I won't bad mouth the competitor. However, here's a million other reasons why we are 10,000 times better, even though we're much more expensive.

Alex Kouts: [00:32:01] But if that's how they're making their decision, that's so crucial to be able to do that. So the next thing is your interest. Now this, this is really interesting. There's a reason that I put this in the worksheet. It's important for you to understand what you're trying to achieve. Now sometimes that seems like it's really obvious, but often it isn't. There's a lot of reasons and negotiations that you do deals that may not be just about the money for instance. As a business person, you may do a deal with a competitor for a strategic relationship to develop a relationship with someone else that they work with, for brand value, for a control terms of your own company or a new term. There's all kinds of reasons why you want to do a negotiation. It's not just about money. It's very shortsighted to think of it that way.

[00:32:38] So spending the time to actually sit down and think of all these strategic reasons why it would be useful for this to close a is a really good sense of things. Now the other side of that that's really important is writing down your goal. So what is your target? So let's say I'm doing a job offer scenario because this worksheet works for everything. What is my goal? What is the amount of money that I want to have? What I think is realistic and would be like an optimal outcome for me? And then most importantly, and if you don't write down anything else on the sheet, on the inverse of your goal, write down what your resistance point is. So many times people walk into a job and they get an offer and they take it even though that offer is below what they think they're worth.

[00:33:17] And interestingly enough, that is actually way, way, way worse in some cases than being unemployed. Now sometimes we need money, you have to take care of our families and we don't get to make that choice. And I understand that. I've worked with a lot of people that have that issue. But I will tell you that underemployed people tend to be very toxic as employees later on down the road. So as an HR manager who's hiring someone, often they want to get them in the door for an amount that's going to make them happy so they don't become a toxic employee later down the road. And when you are in the middle of a negotiation, when you're under duress, when the spotlight is on you, you have this social and kind of emotional imposition to take an offer, no matter what it is, it's harder for me to say no because the lights on me.

[00:33:58] So write this down. So when you're in that situation and it's harder to say no, you make it a little bit easier to stick to your guns.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:34:04] That's interesting. I never really thought of the fact that people who are underemployed or under-compensated become toxic later. I mean, it makes perfect sense, but you would think that the employer would always be trying to go for the lowest amount. But actually that's a rookie mistake seemingly.

Alex Kouts: [00:34:20] It'd be really bad. And you know, most people don't do that. They want to get you in the door for what you think is fair. It's your perception of equity that they're optimizing for in many cases. So once you've gone through that stuff, your interest, you also want to write down options. So in business to business contracts let say I’m doing vendor or contract management or negotiation, there's a ton of different options. Good B2B sales folks, this is really where they shine. They write down a million different things they can throw in. So let's say I'm selling a SaaS or a software as a service product to accompany. In reality, most software-based businesses have zero variable costs. So for every additional customer they sign, it doesn't really cost them anything. That's why venture capitalists love investing in tech businesses so much because as they make more money, their costs don't scale in line with the money they're making.

[00:35:04] On the inverse, if I am running a consulting business, in order to make more money, I have to hire more people. I've got to pay more people. My variable cost is linear. It grows as my revenue grows. Ideally, it grows at a slower rate than my revenue, but it's still growing fast. So again, the options that are available to you in a negotiation are limitless in B2B contracts. With the job offer scenario, it may be more bounded. So I'm going to negotiate a job offer. This is something you and I've talked about before. I could offer to say, listen, I can start next week because I don't need it to be a vacation. That's one option I can throw on the table. Another as an option of something I can ask for. So one thing that you brought up actually a couple of years ago, which I hadn't heard before, was a friend of yours, when he was negotiating job offers, said that he wanted to get lunch with the CEO once before.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:35:49] Right, right. He called it being close to the crown, which I thought was so clever and I don't know if he made that up, or if he'd gotten that from somebody. But that was a very tech sounding thing for me. And I think he was working at, I don't even think I'm allowed to say what it was. It's a very large social networking company and one of the things that he wanted to do is twice a year he wanted to have lunch with this very well-known founder of that company and they were like, this is impossible. And he's like, “Well that's really important to me.” And they offered him a little bit of extra whatever it was, I don't think it was cash, but it was like a paid vacation. He was like, “No, I'd rather have the lunch.” And they gave him the lunches, and it ended up being really beneficial to him because he was able to not only have essentially some kind of working friendly relationship with someone who is constantly putting rungs between his position and the founders in the C-suite. But he would have a direct connection with them, which no one else did. Even people who are also probably right below the C-suite never had any contact with them. He also got picked for different projects. He was top of mind for a lot of things. Because when they were looking for someone in his department, the founder would say, what about that such and such guy? I had lunch with him a few months ago. He seems like a sharp guy, and then they would go, “All right, well you got handpicked by the guy himself, so you're in.”

Alex Kouts: [00:37:05] Super smart. I love that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:37:06] Yeah.

Alex Kouts: [00:37:07] So rounding out that worksheet here. So once I've gone through again what I'm negotiating, the timeline, the parties involved and what they want, my interests, my goals, my resistance point, I also, and the options I have available to me for negotiations, I'll write down my BATNA, my Best Alternative To Negotiated Agreement. If I don't get this car, I'll get another car. If I don't get this house, I’ve got another house, if I don’t get this job, another job, I'll also write down the last two things are communication, strategy. So what channel do I want to use for communication for this negotiation? For job offers negotiations, I often recommend that people do it by email because it's harder for them to kind of control their emotions via phone. It's harder for them to select their words carefully and at least run them by other people and say, “Hey, how do you feel about this wording or that?” So email tends to be good for that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:37:49] And it's in writing.

Alex Kouts: [00:37:50] And it's in writing. Yeah. Which is great, definitely the lawyer comment, you get credit for that one.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:37:56] Oh, we didn’t say you have unlimited paid vacation. We said you had unlimited vacation. Oh, hold on, here's you literally saying this.

Alex Kouts: [00:38:01] Exactly. Definitely smart. You know, I'd say for business to business stuff, I would always do it in person. Always if you can. Especially if you are the ones selling something, always be in person with them. Always generate a physical emotional relationship. We had sounded a little bit too much. Not romantic, a professional business physical relationship. Right. Exactly.

[00:38:19] And then lastly, just a scratch back. What information do you need? What questions do you need to answer? So the whole point of this sheet is to approach negotiation as though you are studying up on something that you really need to understand and do well. And I will tell you that, you know, I don't print this sheet out and fill it out every single time I do negotiation now. But you can bet your ass I know every single one of these things reflexively before I walk into a place where I'm negotiating with someone.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:38:41] We'll make the sheet available on the website. It'll be inside the worksheets for this episode. It'll just be a page of that.

Alex Kouts: [00:38:47] Awesome. So the next one that we have here, and this is something we alluded to before, is this notion of something called social costs. So social cost is this really weird kind of elements of behavioral effect that we're not always aware of, but affects our choices and our feeling of options and all kinds of things on a day to day basis in many ways in which we're not aware. This is that thing we were talking about before. It's very closely tied to the social fabric.

[00:39:11] So in many cases in negotiation, the other side of the table will unknowingly try and increase the social costs of people saying no to them. So they'll say, This is a really great deal. We're giving you a great price. This is really lucky. There's a rebate this month. This is not something that you normally get. You're really lucky, right? To make you feel like you're getting a great deal to make you less likely to want to negotiate.

[00:39:32] Now they're not actually saying don't negotiate. They're not saying that they're not negotiable, or that there isn't an opportunity to be flexible on price. They're just making it seem like they're not flexible on price through a lot of implicit things. They're effectively like incepting you like Inception, like Leonardo DiCaprio's coming into your dreams, and he's like making you believe something that isn't necessarily real. Now, on the flip side, you want to increase the cost for other people asking you for things that you don't want to give up. And this happens all the time. So this could be, for instance, a boss talking to an employee. The employee is going to ask for raise as they typically do at their quarterly or annual review. And the boss knows this, but the boss doesn't want to give a raise. Maybe because they don't have the budget, or it's going to be uncomfortable for them, but the employee really wants it.

[00:40:15] So ahead of that, the boss may drop a bunch of hints saying, okay, well you know, it's been a really rough quarter. Nobody's getting bonuses, there's no title escalation happening for anyone on the team. We're just kind of all hunkered down right now. Not saying you can't have a raise, not even mentioning that, but knowing that that's going to affect your willingness to ask that question when you sit down for a review. So this is something that affects us in ways that we are not aware of in most cases. And the first step is just being aware that it's happening. Being aware of like, why do I feel uncomfortable asking for this thing? Why do I think so? Because what we often do is we're taking our internal monologue of our insecurities around something often contributed to by other people and projecting them into real factors that affect the equation of negotiation when in reality they don't, we're still imagining them.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:41:00] Can you give us an example of social cost or ways in which this happens? Yes. That you're really lucky kind of situation. I feel like a lot of people might see through that in some ways. Maybe not in real time. Is there anything that's a little more nuanced that you've experienced?

Alex Kouts: [00:41:16] Yeah, absolutely. So, let's talk to a couple of them. So one of the big examples is a car salesman. So let's say I'm going in and I'm buying a car, and the car salesman comes out and maybe I'm with my girlfriend and he goes, “Oh, what a beautiful couple.” “Oh, my wife and I, here's a picture of us.” “Oh, here's my kid. He loves baseball.” “You guys love The Giants. I love The Giants too.” And he goes to this whole thing, humanizing himself to us, making him seem like he's really our buddy, and then him saying, you know what? Let me put together a really great price you guys, and I'll come right back. In reality, what he's doing is he's making himself feel like there's this manufactured relationship that I'm going to be less likely to put the screws to him and I'm going to be more likely to believe that he's really doing me a favor. That's him increasing the social costs, putting the social contract in my face to make me less likely to want to negotiate with him.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:42:00] Okay, interesting. So yeah, it's not just humanizing for the purposes of developing rapport, but because he knows that later on you're less likely to say, this is something I need to. I need this much off. I need you to throw in the floor mats or whatever.

Alex Kouts: [00:42:14] Exactly. Yeah. And you know, another great example of this is funeral directors. It's interesting. I had been working on a project that has to do with kind of death management and funeral management lately.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:42:23] You're always on the cutting edge of stuff no one else wants to deal.

Alex Kouts: [00:42:27] Yeah. So the interesting thing is when you're planning a funeral, and I’ve, you know, either directly or indirectly plan a lot of funerals in my life, unfortunately. But a funeral director will take advantage of the fact in many cases, not all cases, but in many cases, take advantage of the fact that you are grieved, that you're not in a position to make optimal decisions when it comes to how much money you're willing to spend.

[00:42:51] So for instance, many funeral homes get busted by the SEC, or the FTC because they don't publicly disclose prices, although they're supposed to, because they know once they have you sitting across the table from them, you're less likely to think about negotiating price because it feels distasteful. There's a high social cost for that because really you should be focusing on the right event for the loved one who just passed away and they exploit that emotional weakness to their business benefit unfortunately.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:43:14] Yikes.

Alex Kouts: [00:43:15] Yeah. So in that situation, just the area that you're in, the context, the emotional context of the situation is a very high social cost for your negotiating for the things you want, but you still can.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:43:25] Yeah. So we didn't really on the, is it the defensive here because people are, who are, the problem is normally we're negotiating with people who negotiate every day and we're doing it once this year. Whether it's our boss manager or hiring manager or a salesman of some kind because salesmen negotiate all day every day for every sale they make, and you hopefully don't have so many people, you know, dying or buying so many cars that you have tons of experience doing this yourself as well.

Alex Kouts: [00:43:54] Right. Yeah. You know, it's interesting. It can work for you and it can work against you. It works against you in the obvious ways, in the sense that they're just ready for it and you may not be as ready for it. They've heard probably a lot of the things that you're going to say, but it also works for you in the sense that they are highly incentivized to make a deal. Any situation in which someone is incentivized monetarily or emotionally to make a deal, you can almost always negotiate. Plus they have a direct understanding of where they can go.

[00:44:19] It kind of goes back to a metaphor I use a lot in terms of poker. I played a lot of poker growing up and one of the interesting things about it is that it's a lot easier to play poker against a good poker player than a shitty poker player, which is true.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:44:31] Because you can predict their actions a little bit.

Alex Kouts: [00:44:32] Exactly, yeah. The poker player doesn't know what they're doing is all over the place. They're, you know, raising you with a 72 off suit, which is a really bad hand and just doing crazy stuff cause they don't know any better. They're making decisions that they aren't necessarily aware of or optimal or not. But you know, in the same thing in negotiation, if you're working with a pro, they probably already have places they can go and they know exactly where they can go. So the barrier for you getting that tends to be a little bit lower than if they had to like find that shit out midway through our conversation with you.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:44:58] That's a good point because you know, if you're negotiating with another, let's say another attorney for a settlement, you know that they want to create a settlement. You also know you might have some idea of what the other party can afford. You obviously have some idea of the amount of damages or what makes it, what it's going to cost for them to go to court and litigate it instead. And I remember in law school negotiating really hard with two really smart guys. This is a mock exercise, of course, these are really good students, but they were terrible at the negotiation thing. And in the middle of it, they go, look guys, we can't go down any further. This is the bottom that they said that we could do on the sheet. Here's our sheet. We're not allowed to go any lower. So, which is by the way, never do that and negotiation.

Alex Kouts: [00:45:39] Yeah, right. Maybe don't say that. So we got the bottom price and then we made them throw in a 10 dollar gift certificate to Bed Bath and Beyond on the top of the settlements.

Alex Kouts: [00:45:48] Just the ultimate smacker face.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:45:50] It’s the ultimate, yes. Can't go below the amount, but you can give us something as well. And so in this case, really knowing that information and making sure that you can predict at least some of the past that they'll go through, is a huge advantage.

Alex Kouts: [00:46:06] Huge advantage. Yeah, for sure. I had a friend years ago it’s a side story who helped write the customer service escalation of concern book for customer service reps for a major us carrier. Rhymes with shmirizon.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:46:23] A lot of things rhyme with shmirizon, though. Good luck figuring that out.

Alex Kouts: [00:46:2] I know they do. Yeah. It really a Da Vinci Code over here. But anyway, he wrote this book that basically said there were magic series of phrases that would automatically escalate someone to a point eventually where this, shmirizon-type company, would basically just give them whatever they were asking for, but they had to keep escalating to a manager, escalating to a manager. So because they're dealing with such a high volume of people, they already had all these escalation paths written out explicit for people on the phone. And by just escalating to a manager every single time, eventually they're just going to acquiesce to almost anything that you ask for.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:46:54] Because whoever you're on the other end of the phone with their time is more valuable than them trying to fight whatever you're asking for.

Alex Kouts: [00:47:00] Yeah, there's 5,000 pissed off people in the queue behind you. I got to move on.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:47:04] Okay.

Alex Kouts: [00:47:05] So that brings us to another really interesting one.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:47:07] Interesting.

Alex Kouts: [00:47:08] So in a negotiation, you, you really, really never, ever, ever, I'm going to use a lot of repetitive words here. Ever, ever, ever, ever, ever want to make the first offer. You hear that a lot. But let's unpack that a little bit. Now, the reason you don't want to make a first offer in a negotiation, let's just take a job offer scenario as an example. When an HR representative asks you, what's your salary expectation? Now in California, they can't legally ask you what your past salary is because that's been deemed to be a purveyor or kind of extension of some type of like institutional bias, which I don't necessarily agree with. But let's just say that that is the case. So they can't actually ask you that. But so often they will still ask you what are your salary expectations? What do you want? And they'll even try and make it easier on you and say, what's a range that you're thinking? Which is stupid because they're only asking for the low number in the range. The high number doesn't mean anything, but you never want to give them that answer. You want to figure out a polite way to decline that. So someone asked me, “Okay, Alex, you know, we're really interested in making you an offer. What's your range? So we can make sure we're in the same ballpark and give you a good answer or give you an offer. I'll say, “You know what? I'm comparing this offer this job to a number of other opportunities, I'm looking at and based salaries only one of the factors. If you could make an offer, I'd love to compare it to other things, I'm looking at. I’m really looking forward to it. Thank you. I will never give them a number.

[00:48:25] The reason is there's this concept in negotiations called information asymmetry, and this is one of the driving things in economics as well in business, in general, is that I know something you don't know and you're willing to pay for that information. Now in a negotiation, it's very similar. If for instance, their range was 100 to 200k, and I came in and said: “95, they're going to go.” “Here we go, 95k, that's great.” But I'm giving up potentially money. Now, even if that isn't the case, the probability that that is even possible is never worth testing or giving up. So in a situation where you have imperfect information, let the other side make the offer. Now, there's some situations where that is, there's an exception to that. One is if you know you have really good reason to believe the other party is going to come in super low.

[00:49:10] So that's the Craigslist example. So if I'm selling a couch on Craigslist, I don't say, “Make me an offer.” I say “400 dollars is our best offer,” because otherwise I'm going to get everyone saying, “Ah, screw you. I'll take the couch for free.” Right? Because I know they're going to come in low. That's the whole point of it. So absent of that like specific situation, never make the first offer if you can avoid it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:49:30] Is there any time that you've had somebody refused to make the first offer when you've dodged or declined?

Alex Kouts: [00:49:36] In job offers scenario is extremely rare because that person's entire job, and HR representative or recruiter is to give you the offer and get you in the door. So they're going to make the offer. But yeah, I've had situations where people are really stubborn, but you know, the most power negotiation sides with a person or resides with the person who's willing to walk away. So if the other side just go silent and we'll give you an offer, walk away and look for other things and eventually, they will come back and give you an offer if they want to make this deal.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:00] Good point. Okay, excellent. I can't remember that time that which that had happened. I know it's happened though. I remember them saying, “I'm sorry we can't tell you, you know, the initials and look, we'll just give me a ball.” “No, I'm sorry I can't,” well look, you got to start somewhere. Well, you tell us what you're looking for, and I can't remember what this was, but it was just continual.

Alex Kouts: [00:50:20] Yeah. Sometimes that happens with really hard to price things like services or like, you know, someone's buying a company or like that. But you know, absent a situations like that that are incredibly ambiguous and free form, it's very, very rare.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:34] That makes sense. All right. Good to know. So we won't worry about that.

Alex Kouts: [00:50:38] Exactly. So I'm glad you said good to know, because the next one that I wanted to talk about here is the power of the word no.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:46] Ah, the different no.

Alex Kouts: [00:50:46] The different no. Exactly. N-O-W. No, that's now.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:49] No, that's now.

Alex Kouts: [00:50:50] Oh God. Yeah. I've been in a booth too long. So getting to no. No is such a beautiful word. As we mentioned before, the worst thing in a negotiation is a fast yes. So someone goes, okay, “How much do you want for it?” You go a “100 bucks.” You go, “Yes. Shit.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:51:05] Yeah. This is like the Seinfeld episode where Kramer is in court suing Starbucks, I think. And they said, “All right, we're willing to settle for free coffee for life.” And he stands up and goes, “I'll take it.” His lawyer just melts down and crumbles.

Alex Kouts: [00:51:19] Exactly. Exactly. Yeah. I mean when you get a fast yes in a negotiation, it means you priced the situation incorrectly. It means you weren't aware of the information asymmetry and you made a bad call for the most part. And so in a negotiation, you need to love the word no, because no is what tells us where the ceiling is and what tells us where the edges of the conversation are. Until you get to no, in many cases you can't even have a negotiation. People are just giving you things.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:51:44] Huh, okay. Right. Yeah, that's true. If there's no resistance, there's not really a negotiation going on at that point.

Alex Kouts: [00:51:51] Exactly. You're just asking for stuff in your head and you're getting it. No, again, is the operant word that tells you where your kind of, where your boundaries are. So when I was in grad school, I had a professor who taught negotiation. She was brilliant. And she had us go out as a class exercise when our first homework assignments and get 20 nos. And she'd just go out and just ask for stuff and just see what people say. And so I went out that week, we had an entire week to do this, and I went out to McDonald's and I'd be going around to the, you know, the drive-through, and I'm like, “Okay, I'd like a cheeseburger and a milkshake.” She goes, “Great, that'll be, you know, 7.50.” I'd be like, “All right, how about like 6.50, and she goes, “Okay, fine. Just come around.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:52:28] Really?

Alex Kouts: [0 0:52:27] I'm like, “What?” I’m like “What is going on?”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:52:30] Really? You negotiated at McDonald's?

Alex Kouts: [00:52:31] Well I just asked for something. I asked for something that I thought there was no way that I would get it. Because this a McDonald's, they sell like a billion burgers a day, there's no way they're going to negotiate on something.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:52:39] She probably just paid the dollar out of her own pocket, the poor thing.

Alex Kouts: [00:52:42] Yeah, or they don't care, like in many cases. And you know, I was at a restaurant and I'd say to the waiter, “Okay, I want free dessert but I'll tip you more.” “Yeah, okay fine.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:52:52] I’m pretty sure that’s not, and he got fired for that. But you got your negotiation.