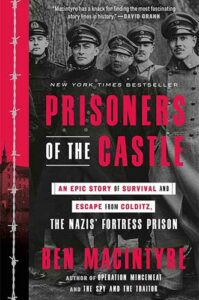

Join us for adventure with Ben Macintyre, author of Prisoners of the Castle: An Epic Story of Survival and Escape from Colditz, the Nazis’ Fortress Prison!

What We Discuss with Ben Macintyre:

- How Germany’s Colditz Castle — around in some form or another since 1046 — came to serve as a Nazi POW camp for high-ranking officers of the Western Allies during World War II.

- How concentrating Allied officers who had previously escaped from other camps — or were deemed a high-security risk — into one place turned Colditz into a highly competitive “escape university.”

- Why the hodgepodge layout of Colditz (known as Oflag IV-C during the war) made it a terribly inefficient prison — from which more than 30 successful escape attempts were made between 1939 and 1945.

- Plans for more than 300 escape attempts made over the years involved everything from clever disguises to hand-dug tunnels to a glider made from bedsteads, floorboards, cotton sheets, and porridge.

- What happened to Colditz and its prisoners after the war?

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

For countless reasons, those of us currently enjoying civilization should be grateful the Nazis (you may remember them as the bumbling bad guys from Hogan’s Heroes, Indiana Jones movies, The Sound of Music, and the January 6th insurrection) lost WWII. Aside from thwarting the spread of fascism and genocide that killed 11 million people, we’ve also been made privy to the inspiring feats of derring-do enacted by the heroes of Ben Macintyre‘s Prisoners of the Castle: An Epic Story of Survival and Escape from Colditz, the Nazis’ Fortress Prison.

On this episode, Ben joins us to discuss how a medieval German castle was transformed into a POW camp during WWII for Allied officers who had previously escaped from other camps — or were deemed a high-security risk. We explore why concentrating this troublesome demographic into a hodgepodge labyrinth of buildings assembled over several centuries made it an ideal “escape university” from which 300 attempts (and 30 successes) were made between 1939 and 1945. Here, we examine the clever levels of one-upmanship and innovation that prevailed during these attempts and get a fresh perspective on the challenges faced by prisoners of war and the resilience of the human spirit during one of the darkest periods in history. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. We appreciate your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini-course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- Quince: Go to quince.com/jordan for free shipping and 365-day returns

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- AG1: Visit drinkag1.com/jordan for a free one-year supply of vitamin D and five free travel packs with your first purchase

- Jaspr: Visit jaspr.co and use code JORDAN for 25% off Jaspr Pro

- The Adam and Dr. Drew Show: Listen here or wherever you find fine podcasts!

Miss our first two-part conversation with Jack Schafer? Start getting caught up with episode 467: Jack Schafer | Getting People to Reveal the Truth Part One here!

Thanks, Ben Macintyre!

If you enjoyed this session with Ben Macintyre, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Ben Macintyre at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Prisoners of the Castle: An Epic Story of Survival and Escape from Colditz, the Nazis’ Fortress Prison by Ben Macintyre | Amazon

- Other Books by Ben Macintyre | Amazon

- Ben Macintyre | Website

- Ben Macintyre | Twitter

- Ben Macintyre | Facebook

- A Tale of WWII Derring-Do That Reveals the Humanity of Its Heroes | The Washington Post

- Colditz Castle | Schloss Colditz

- Castle Wolfenstein | Wikipedia

- The Colditz Story | Prime Video

- Attempts to Escape Oflag IV-C | Wikipedia

- Escaping Disguised as a German Officer | Discerning History

- Distinguished Service Order (DSO) Lieutenant Am (Mike) Sinclair KRRC | The Royal Green Jackets (Rifles) Museum

- Hitler Issues Commando Order | The National WWII Museum Blog

- Escape from Colditz! The British Plan to Glide Out of Colditz Castle | The Untold Past

- Colditz Castle: PoWs Found the Wine Cellar, Drank the Lot, and Refilled the Bottles with Urine | War History Online

- Red Cross Parcel Delivered to WWII Allied Prisoners of War at Colditz | Alamy

- Reinhold Eggers | Wikipedia

- Florimond Duke | Wikipedia

- Colditz Heroes & Villains | Key Military

- Christopher Hutton | Wikipedia

- The Shawshank Redemption | Prime Video

- The Great Escape | Prime Video

- Jimmy Yule Dies at 84; British POW Bamboozled Nazis | The New York Times

- The Radio Hide in Colditz Castle | Glen Bowman, Flickr

935: Ben Macintyre | Escaping from a Nazi Fortress Prison

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:03] Ben Macintyre: Bear in mind that for all the attempts to escape from Colditz, only 16 people achieved what was called a home run. Only 16 people actually managed to get out. And think of it that an escape is taking place once every three days. But only 16 men actually managed to get across the borders and back to their home countries, so the chances of success were very low indeed.

[00:00:29] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people and turn their wisdom into practical advice that you can use to impact your own life and those around you. Our mission is to help you become a better informed, more critical thinker through long-form conversations with a variety of amazing folks, from spies to CEOs, athletes, authors, thinkers, performers, even the occasional gold smuggler, investigative journalist, Russian chess grandmaster, or cold case homicide investigator.

[00:00:58] And if you're new to the show or you want to tell your friends about the show, I suggest our episode Starter Packs is a great place to begin. These are collections of our favorite episodes on persuasion, negotiation, psychology, geopolitics, disinformation, cyber warfare, crime, and cults and more to help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started.

[00:01:21] Today's episode is a bit outside the norm. It's a historical story about an old Nazi prison and the insane escape attempts that went on inside, well, and outside the prison. Fascinating human innovation at play, and I seldom dip into history like this, but some of the innovative thinking and execution and their attempts to evade the guards and escape from this prison, well, they're frankly really unique and caught my interest.

[00:01:44] And if you're into history, especially World War II stuff, this is going to be right up your alley. If not, please go grab another of our 900 or so episodes, especially if you're new to the show and you want to hear a more typical episode of this podcast. All right, here we go with Ben Macintyre.

[00:02:05] Tell me about Colditz first. What is this? Because when I first heard about it, I don't really do history episodes generally, it's just something that's a little outside my wheelhouse for this show. It's not that I'm not interested, but I just immediately picture Castle Wolfenstein, if you remember that old video game with the Nazis and the prison castle. It's essentially the same, very similar thing.

[00:02:25] Ben Macintyre: It's not a million miles away from that idea. Actually. It's a huge gothic castle on the edge of Germany in Eastern Germany. It's enormous. I mean, it's a massive great thing dominating the skyline above the little village of Colditz. And it was built by the electors of Saxony who were the hereditary rulers of that part of Europe.

[00:02:44] And it was intended to all the local population to demonstrate his great wealth and power, and also to incarcerate people. It always had a prison aspect to it, but it does look like Dracula's Castle. I mean, it's huge great thing dominating the skyline with sort, I mean, Bram Stoker couldn't have made it out. I think it's got something like 740 rooms.

[00:03:06] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:03:06] Ben Macintyre: It is properly massive.

[00:03:09] Jordan Harbinger: This is probably not something you know the answer to, but I'm curious how much did it cost back then to build something like that And then I can do an inflation calculator for today's money, unless you happen to know that too.

[00:03:19] Ben Macintyre: No, I've no idea. I mean, the answer is heaven knows because it was started to be built in the 11th century.

[00:03:26] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, okay.

[00:03:26] Ben Macintyre: We are going back a millennium here.

[00:03:28] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:03:28] Ben Macintyre: And then it was added onto over the years with different wings and different courtyards and different bits and pieces. I mean, it's really, it's not a castle so much as a palace.

[00:03:38] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:03:38] Ben Macintyre: That's the way to think of it. It was intended to be a massive expression of power and wealth. Then it went through all sorts of different kind of forms as history unfolded. In the 19th century, it was used as a hospital and then as a prison asylum. It was used for people who were mentally ill. Then it became a prison camp. The Nazis used it briefly as a concentration camp.

[00:04:01] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:04:01] Ben Macintyre: For their political enemies. And it wasn't until the beginning of the war that it was turned into the biggest and most secure prison for prisoners of war, allied prisoners of war.

[00:04:11] Jordan Harbinger: It's strange because it, it doesn't feel that secure. And we'll talk about that in a minute. because that's kind of what the whole book is about. You start the book with this disguise escape attempt. Take us through this. because it's probably one of the more ridiculous things that I've ever heard. And it sounds like a Charlie Chaplin attempt at escaping from prison.

[00:04:29] Ben Macintyre: Doesn't it? But it very nearly worked. It was right in the middle of the war. This was after Colditz had been established for some years. One evening, somebody who looked exactly like one of the prison officers with a big mustache and sort of whiskers made his way round the parapet with two guards in attendance and dismissed the guard at the front gate, and the guard was just about to leave when he spotted something a bit odd about this character.

[00:04:56] And the truth is he was completely in disguise. His mustache was made of sort of bits of shaving brushes. Dyed with kind of special red ink to make him look convincing. He'd been practicing the accent of this particular German officer for months. The entire uniform and the uniform of his two accomplices had been fabricated out of different bits of material they managed to obtain over the course of the time inside.

[00:05:23] It was an amazingly complicated plot, and if it had worked and it didn't at the last moment, and in fact this character ended up being shot in the chest, he survived, but the guards opened fire on him. There were actually about 40 prisoners waiting in an upper room, and as soon as they got the go ahead, they were going to come down on ropes, made out of bedsheets and staged the first and biggest mass escape from Colditz.

[00:05:46] But that's just one of many, many hundreds of escape attempts. Because this peculiar thing about Colditz was that it was intended to be a prison that was impossible to escape from, and therefore the Germans hid in it or locked up inside it, all the prisoners who had tried to escape from somewhere else, which was actually an extremely bad idea.

[00:06:09] Because if you lock up all the most difficult prisoners, all the recalcitrant ones, all the ones you've tried to escape from somewhere else, what do they do? They encourage each other to escape. And Colditz is very swiftly, very early on in the war, became a kind of, it became almost an escape university. Everybody in it was competing with everybody else to get out of it.

[00:06:30] And the other problem with Colditz was that actually, while it looked very impressive and and very frightening and menacing and was surrounded by barbed wire and searchlights and dogs and guards, it was actually a really bad place to put a prison because it was so old. It was actually sort of full of holes. I mean, it was, you know, it had so many bits and pieces built onto it over the years. It had five different sewage systems. It had tunnels all over the place. It had hidden compartments.

[00:06:56] Actually, it was just a really bad place to put a prison. Because the best place to put a prison camp, or particularly a prisoner of war camp, is a big field surrounded by barbed wire. That's how you stop people escaping. This proved extremely difficult to stop people from trying to get out. And so it became a kind of tussle really between a sort of cat and mouse game between the guards and the prisoners.

[00:07:18] Jordan Harbinger: It kind of reminds me of how people go to prison, even in the United States and they come out and they have all these connections and they've got all these different ideas for — not all inmates, obviously — a lot of people come out wanting a normal life, but guys who are career criminals often come out with just more ideas, more gang connections, whatever it is. And that's what it sounds like. It sounds like all the class clowns put into one class and instead of, okay, they got the strict teacher, that teacher's classroom is just on fire because he's got 21 class clowns in one class.

[00:07:47] Ben Macintyre: That's exactly right. And in fact, it's interesting that you should mention teachers at this point because the head of security at Colditz, the German officer in charge of trying to keep these difficult prisoners inside had been a school teacher and he treated the prisoners if they as if they were basically naughty school boys. He knew very well that if you put all the bad boys in one place, they become completely uncontrollable.

[00:08:09] And that's more or less, in a nutshell, the story of. It became hugely celebrated after the war as a symbol of resistance to Nazi domination, but done in a different way. This wasn't about guns and bombs and bullets. This was about imprisoned men trying to show that they were not going to be driven down by the experience of imprisonment.

[00:08:33] Jordan Harbinger: The castle being built in layers with all these secret passages and tunnels and canals and stuff. It almost sounds like, did the Nazis not know that when they put people in here? Because it seems like it's almost like the worst possible prison that you can have when there's a bunch of ways to secretly go from one room to another, go underneath the prison, go over other rooms. The locks are all old. It's just, it's almost like you would just have been better off locking these people up pretty much anywhere else.

[00:09:01] Ben Macintyre: Well, that was what they realized with hindsight. But once it was underway in a slightly Germanic way, they didn't go backwards.

[00:09:09] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:09:09] Ben Macintyre: You know, once it was established that Oflag IV-C as it was designated an officer's camp, IV-C was going to be, you know, the celebrated high security prison, that is what it remained. And one shouldn't exaggerate this, while the prisoners tried to escape and mounted many, many escape attempts, actually the Germans got very good at stopping them.

[00:09:32] So every time there was a failed escape. This man, Reinhold Eggers, who was the head of security, would simply plug the hole. He'd find out what had happened. He would increase the guards. He would cement up whatever fissure they'd managed to crawl out of. And so as time went on and as the war dragged on, it became harder and harder to escape from Colditz.

[00:09:51] It also became more and more dangerous because Hitler, about halfway through the war, passed something famously called the Commando Order, which meant that anybody discovered outside the prison, any allied officer or any allied soldier in civilian clothes was to be shot as a spy.

[00:10:09] Jordan Harbinger: Mmm.

[00:10:09] Ben Macintyre: And so while the initial escape attempts were in a way, a sort of game, you know, between the officers and their prison guards, as time went on, it became incredibly dangerous. It became actually, at some points, positively suicidal to try to get out of this prison. So one can't exaggerate the number of escapes because at one point, I mean, in the first three years of the prison's existence, there was one escape attempt roughly every three days. I mean, it happened all —

[00:10:36] Jordan Harbinger: That's ridiculous.

[00:10:36] Ben Macintyre: — the time in different forms. Yeah.

[00:10:38] Jordan Harbinger: With that many escape attempts, the fact that there were even guards there at all, and they still had one every three days, just shows you how aggressively these people were trying to get out of there. Because generally, if you're trying to escape a president, I assume it takes weeks or months to plan this thing.

[00:10:51] And if there's one every three days, these aren't sort of ham-fisted attempts, right? The one we just talked about where they dressed up as one of the guard commanders and they made a fake mustache and a fake uniform out of just random objects they found in the prison, right? They didn't find official pins and ID cards and weapons. They made different things look like that, right? So a screw from a bed here, a little piece of tile that they dyed with something else to look like a metal or epaulet pin. I mean, they're taking a lot of time and energy to put these into place. So these guys are spending all of their time figuring out how to escape and then pursuing those escape plans.

[00:11:27] Ben Macintyre: That's exactly right. And the escape attempt we've just described was by no means the most complicated or sophisticated of them. I mean, the one I particularly love, which took place towards the end of the war was they actually built a glider in order to try to fly out of Colditz. And actually this thing was built, and it was a miracle of aeronautical engineering.

[00:11:49] They worked out that if they could build this thing and then quite literally catapult it off the roof, they would be able to be airborne for long enough to get two prisoners out. And it took six months to build. It was built out of hundreds of tiny bits of wood metal from the bedposts. It was wrapped in mattress covers that had been soaked in porridge in order that they should tighten around it.

[00:12:12] And then the idea was they were going to build a runway on the apex of the highest roof in Colditz. And then they were going to get a bath filled with cement and a system of ropes and pullies and drop it off the end of the roof. And then this system was going to literally throw the glider into the air for just long enough to get it airborne. It was an astonishing feat. And that was sort of representative, if you like, of the great sort of feat of imagination that went into a lot of these escapes.

[00:12:42] The other thing I should probably mention is that while Colditz is very much part of kind of British historical memory, this was an international camp. They weren't just British soldiers in here. They were French. They were Dutch, they were Polish in huge numbers. They were Belgian. And in the latter part of the war, they were American. There were American prisoners inside Colditz. And one of the more extraordinary aspects was that they all began to compete with each other to try to get out.

[00:13:08] There was a kind of, if you like, a kind of league table of who was getting the most escapes, who was being most successful. So you've got this strange situation where they're not only competing against each other to get out, they're competing against different nationalities to get out.

[00:13:22] Jordan Harbinger: That's so funny. And also somehow makes perfect sense, right? Like, "Did this guy get out?" "Yay." "I mean, he got shot at the border." "Well, it still counts. He got out of the prison." "All right, fine. We'll give that one to the Dutch, but we need to catch up." Right? And then the French are sitting there just being a little bit lazier than everyone else. And the Brits are frustrated.

[00:13:41] Ben Macintyre: Well, the British typically, of course, the British became extremely jealous of the French.

[00:13:45] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:13:45] Ben Macintyre: Who they felt were doing much better than them at the beginning of the war.

[00:13:49] Jordan Harbinger: That's funny.

[00:13:49] Ben Macintyre: And eventually at one point there were so many escape attempts happening that they were actually undermining each other. They were, at one point there were five different tunnels being built by five different groups inside the castle. And they were tripping each other up all the time. So they set up a kind of international committee, if you like, to discuss and to compare escape attempts. So they didn't cause each other problems.

[00:14:13] And unlike, you know, like most international organizations, it kind of worked for a bit until the whole thing fell apart and everyone started fighting again amongst each other. But it's an extraordinary thing. I mean, and some of these escape attempts were done, as it were in alliance. So the British and the Americans sort of almost naturally allied together to sort of help each other escape from this place. So within the kind of castle structure, you had this strange system of alliances taking place.

[00:14:40] Jordan Harbinger: This stuff all makes the Alcatraz escape attempts sound like third grade science projects, you know? Yeah. Okay. You built a raft, you weren't going to get in the water. Never seen again, probably drowned. It's like, okay, tell call me when you fly off the roof with a catapulted hang glider made out of mattresses and sail into the village below, over the guard towers. Like, call me when you dig a tunnel underneath the whole thing and burst out through a sewer tunnel or whatever the plan was.

[00:15:06] Ben Macintyre: Absolutely. But I haven't even told you about the tunnel. I mean, the tunneling was extraordinary. The French managed to build a tunnel, which was 150 meters long.

[00:15:16] Jordan Harbinger: So this is like 500 feet almost.

[00:15:18] Ben Macintyre: Yeah. And they called it naturally Le Métro after the French under subway system. And that took months to build and they excavated tons of rubble. It even had its own sort of rustic air conditioning system made out of tin cans so they could pump air to the point at the far end of the tunnel to ensure that the tunnelers didn't pass out.

[00:15:41] Astonishingly, it even had a telephone inside it. They rigged up a telephone as a sort of early warning system, so if the German guards were coming, they could alert the tunnelers and get them out of the tunnel before they were captured. It was an astonishing, and something like 80 different people worked on that single tunnel alone.

[00:15:58] Jordan Harbinger: That's really impressive. Did, was it an actual electronic telephone or were they using conducting metal?

[00:16:04] Ben Macintyre: They were using the old telephone system. In fact, they ripped it from the Germans. The other thing they constantly did was steal stuff.

[00:16:12] Jordan Harbinger: Sure.

[00:16:12] Ben Macintyre: They were stealing stuff from the Germans the whole time. I mean, spades, tools, nails, planks, and wiring. Most of the internal wiring of Colditz was ripped out at different points and used by the prisoners for various nefarious purposes. This is why in a way, the story of Colditz has become part of, sort of, particularly of British and French wartime mythology. It's absolutely buried in a kind of Anglo French attitude towards imprisonment.

[00:16:44] Jordan Harbinger: How many prisoners were in there? Did you tell me?

[00:16:46] Ben Macintyre: The numbers varied. I mean, it began with quite a small number. There were about 250 to begin with.

[00:16:51] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:16:51] Ben Macintyre: At one point there were 700 prisoners in there.

[00:16:53] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:16:53] Ben Macintyre: But there were never more than that. Interestingly, the number of guards needed to guard this set of prisoners was almost the same number. I mean, they needed almost as many soldiers to guard them as they had prisoners. It was extraordinarily, sort of, as it were, labor intensive.

[00:17:09] Jordan Harbinger: So these are prisoners of war captured from, were they pilots that got shot down mostly, or the people that were wounded on the front lines and just transported into Germany?

[00:17:19] Ben Macintyre: Both really. I mean, initially most of the prisoners were people who were in the Allied armies captured in the retreat, in the initial retreat of the war. So they were captured at Dunkirk. Many of those who were left behind at Dunkirk who couldn't get off France, when the expeditionary forces were retreating were captured.

[00:17:38] Many were Polish prisoners captured when the Nazis invaded Poland, similarly French prisoners when the Germans invaded there. But as the war went on, increasingly these were commandos captured behind the lines. They were air force pilots shot down. They were those kinds of people. And the numbers grew and grew throughout the war.

[00:17:57] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned the Polish troops stealing beer and showing the rest that like, "What? Where'd you get all this beer?" "Oh, we just picked all the locks," which just comes across as Peek Polish. Right? They pick all the locks only to stay inside the prison and just come back with enough beer for everybody. Well, that's Polish hospitality for sure.

[00:18:14] Ben Macintyre: Absolutely. They brewed their own beer actually. I mean, they began, they, as time went on, they not only brewed, not just the Poles, everybody began brewing different sorts of alcohol. There was even something called Chateau Colditz, which was a kind of homemade wine, made from sort of raisins that have been soaked in in water and expanded sort of more or less back into grapes and then fermented. And then they said it was quite good actually.

[00:18:39] So that's one of the funniest, I mean, one of the things about Colditz, the one has to remember is that it's quite unlike Alcatraz or any other prison where civilian prisoners are held. Because the unique thing about a prisoner of war camp is that first of all, the prisoners inside it are innocent.

[00:18:56] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:18:57] Ben Macintyre: You know, they have committed no crime, so therefore there is a feeling of unfairness that sort of runs through most prisoner of war camps. And the second thing is that unlike civilian prisoners, they had no idea when or if they would ever get out.

[00:19:11] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:19:11] Ben Macintyre: They were prisoners of time and prisoners of the war, so they could only see and hear about what was happening in the war, in the distance, and they couldn't sort of chalk off the days on the wall as it were, like a normal prisoner. So it gave the place a very different kind of atmosphere in that sense.

[00:19:26] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned that there was a German guard, and I say German, but not Nazi because I think a lot of people don't realize that not everybody in World War II who fought for Germany was a Nazi.

[00:19:37] And I was an exchange student in former East Germany, and the grandfather from that family was taken prisoner of war in the United States, and he was in Maryland. He said he loved the food and he wanted to see America. And when he shook my hand, when he met me as an exchange student, he said, "This is the only time I've shaken an American's hand in my entire life. I always wondered what it would be like." And I just couldn't believe it. Especially, because I guess, you know, you don't shake your prisoner's hands when you're, when you're rounding him up.

[00:20:03] But I thought it was very strange and I remember telling my host family, I'm like, "Oh my gosh, he was a Nazi." And they're like, "No, no. He was not a Nazi. He fought for Germany. He was 17 years old." And I thought, okay, it's just an excuse. They want to distance themselves from this. But you mentioned even in the book that the commander in the castle, he's decidedly not a Nazi. Can you take us through the difference a little bit?

[00:20:23] Ben Macintyre: This is a very good point, Jordan. I mean, the thing about prison camps is that they were run by soldiers, by German soldiers. When we think of a prison camp in the Second World War, we naturally think about concentration camps —

[00:20:35] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:20:35] Ben Macintyre: — and the horrors of the Holocaust and the SS run camps that were places of casual and systematic brutality and horror. Prison camps weren't like that, or most of them are not like that. These are tended to be run by the Wehrmacht, by the German army. And the German officer class had a certain respect for Allied Soldiers. They tried to run these camps under the Geneva Convention. They weren't routinely killing people inside them.

[00:21:02] And as you say, only a minority of the German officers in this camp were actually Nazis. Some of them were, some of them had joined the party. But most of them actually had not, which didn't mean they were anti-Hitler. They were determined to win the war. They were patriotic Germans, but they hadn't, as it were, signed up to the whole horrendous savagery of the Nazi project.

[00:21:25] And as time went on, many of them, including the character you are referring to, became increasingly disillusioned by the Hitler regime. They never rebelled against it. They weren't those kinds of people, but they were not full on brutal Nazis. And it's an important distinction because there's a certain honor and a certain civility between the guards and the officers in this camp. There was a certain grudging mutual respect. They were on opposite sides. They were doing their best to make life as difficult as possible for each other. Nonetheless, both sides tried to play by the rules.

[00:22:04] Jordan Harbinger: You are listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Ben Macintyre. We'll be right back.

[00:22:09] This episode is sponsored in part by Quince. I've talked about Quince before and for good reason, their exceptional quality has us weaving their timeless pieces into our wardrobe. Imagine snagging a 100 percent Mongolian cashmere sweater for 50 bucks. Unbelievably soft and cozy. I mean, I guess they brought it all the way from Mongolia for a reason. Jen got their super soft sweater, which she never wants to take off. What's remarkable is quince pricing 50 to 80 percent less than similar luxury brands. Transparency is key. They even show you their production costs and margins. This cost-effective magic happens because they partner directly with top-notch factories, skipping the middleman, bringing us those sweet savings all the way from Mongolia apparently. But Quince isn't all about the bottom line. They're dedicated to ethical, safe, and responsible manufacturing choosing only superior fabrics. I really dig that approach. So this year, I'm pampering my loved ones with quince cashmere sweaters. So we'll be twinning in comfort and style.

[00:23:00] Jen Harbinger: Get high quality essentials at affordable prices for you and the whole family with Quince. Go to quince.com/jordan for free shipping and 365-day returns on your order. That's Q-U-I-N-C-E.com/jordan to get free shipping and 365-day returns, quince.com/jordan.

[00:23:16] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by BetterHelp. In our family, we try to focus on diving into experiences that'll stick in our memories longer than any gadget. It's all about making moments that matter, not just piling up more stuff. And speaking of unique gifts, why not treat yourself to some top-notch self-care this holiday season? Treat yourself to better help. It's like having a therapist buddy who's there for you without even having to change out of your festive PJs. Think of it as mental wellness with a side of holiday cheer, all from the comfort of your couch. With BetterHelp, those aha moments might just be more surprising than Aunt Edna's mystery casserole at the family dinner. So why not just kick back with your hot cocoa and give it a whirl? Your brain deserves a little holiday pampering too. And guess what? BetterHelp all online super flexible fits in your schedule. No matter how busy you are, just fill out a quick quiz. Boom, you're matched with a licensed therapist. Plus swapping therapists is as easy as swapping holiday recipes. No extra cost, no fuss.

[00:24:03] Jen Harbinger: In the season of giving, give yourself what you need with BetterHelp. Visit betterhelp.com/jordan today to get 10 percent off your first month. That's better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan.

[00:24:13] Jordan Harbinger: If you're wondering how I managed to book all these great authors, thinkers, creators every single week, it is because of my network and I'm teaching you how to build your network for free over at jordaharbinger.com/course. This course is all about improving your relationship building skills and inspiring other people to want to develop a relationship with you. And the course does all that in a non-cringe down to earth way. There's no awkward strategies or cheesy tactics. It's just practical exercises that will make you a better connector, a better colleague, a better friend, and a better peer without looking like a schmoozey, networky, schmo. Just a few minutes a day is all it takes, and many of the guests on the show subscribe and contribute to the course. So come join us, you'll be in smart company. You can find the course at jordanharbinger.com/course.

[00:24:55] Now, back to Ben Macintyre.

[00:24:59] You talk about in the book how the Red Cross was sending food delivery, mail delivery. There were chocolate. And it wasn't like the German guards would get these packages and go, I'm taking this food, I'm giving it to my family. They would give them the clothing and the letters and the food that somebody had made for them and the chocolate that even the guards couldn't get because they were in the middle of World War II. The Red Cross is sending chocolate packages to the British and the Americans and the French. And they're just sitting there eating it in front of the guards and smoking their cigarettes. And the guards are like, "Oh man, I wish I got a package from the Red Cross." It was so weirdly civil. It was just a bizarre juxtaposition.

[00:25:37] Ben Macintyre: That's absolutely right. And towards the end of the war, the prisoners were far better nourished than their captors. They were getting things that the Germans only dreamed of getting. And of course, they used these to bribe and barter and to get escape equipment from the Germans. It made the Germans much more vulnerable to corruption in some ways.

[00:25:57] But you are absolutely right. I mean, the Red Cross parcels that were brought into these prison camps, and particularly in Colditz, its stop them from starving. I mean, without them, many of these prisoners would've starved to death, particularly at the beginning of the war. So the Red Cross played an absolutely vital part. But one of the reasons why Colditz was particularly able to get this kind of stuff was because they were officers. I mean, this is again, a very important distinction. These were not ordinary soldiers. These were all men of rank. That meant that they had additional privileges under the Geneva Convention. It was a very class stratified world in those days, and these officers were treated differently.

[00:26:35] If you were an ordinary soldier in an ordinary prisoner of war camp, you didn't have a lot of these privileges. And the other thing about these officer prisoners was that they themselves, believe it or not, had servants to look after them. And those servants were also prisoners of war. They were, you know, British, French, Dutch, but they were ordinary soldiers. They were privates and their jobs were to, you know, cook and clean for the officers. And get this Jordan, they were not allowed to escape.

[00:27:04] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:27:05] Ben Macintyre: If you were an ordinary soldier, you were not on the escape list. I mean, that shows you just how class stratified the whole thing was.

[00:27:14] Jordan Harbinger: That was the most British part of this whole thing that I couldn't really wrap my head around as an American. I mean, not that we didn't have slavery in our country here, it's still a thing. We're sort of dealing with the reverberations from that. But it's very odd to me that you would be in a prison and you'd have somebody of your own nationality and you're just bossing them around and waking them up, and then you're like, "I'm getting out of here. Oh, you're not coming with me. I don't care about you at all. You're basically disposable to me." And then you try to get out of a tunnel and you either escape and never think about that person again, who possibly is going to die after just working for you. Or you get caught and then you're back, and the first thing you say is, "Go get me my shoes or my food, or light my cigarette." It's just so weird that that even existed.

[00:27:58] Ben Macintyre: It doesn't sound weird to our modern world, but in truth, Jordan, it's not really about nationality, it's about military discipline and the way that armies were organized in the middle part of the 20th century. And it'll come as a shock to you to hear this, but, um, not only did the French and the Poles and every other officer in Colditz had servants, but so did the Americans.

[00:28:21] The Americans were not immune to this. They also had, so-called orderlies who were doing the menial work. I mean, in part, the undeclared ban on soldiers escaping from Colditz. Obviously, that didn't apply in other prison camps. Ordinary prisoners in other POW camps could escape, and many of them did attempt to do so. In Colditz, it was slightly different because there was a danger that if they were captured on the outside, the orderlies were much more likely to face lethal reprisal —

[00:28:51] Jordan Harbinger: Mmm.

[00:28:51] Ben Macintyre: — than the officers. The officers, again, because of the sort of code of honor, were really, let's say it, at the beginning of the war, were more likely to be returned to Colditz. If you were an ordinary soldier caught outside the walls, you were much more likely to be shot.

[00:29:03] Jordan Harbinger: Huh.

[00:29:03] Ben Macintyre: There was a good reason why. There was a good practical reason why they didn't, and there's no recorded attempt by any orderly, any ory soldier ever to get out of Colditz.

[00:29:11] Jordan Harbinger: Wow. Again, the civility slash incivility inside is such a juxtaposition. There's, you mentioned in the book, one French officer escapes, they shoot at him, but he makes it to Switzerland. They shoot at him on his way out. Then he writes to the prison and he asks the Germans, "Hey, can you mail me all my stuff? I left a lot of stuff in my cell and I kind of want all that stuff back." And, of course, what you're expecting is them to just burn the letter, like tough crap. Meanwhile, they mail his stuff to him at their own expense, and I just can't wrap my head around it. I'm just imagining this frustrated German commander, like, "Damn it, he's alive. Fine, we will send your things." You know, like that just never happened. Now, we have open grave and Russian concentration camps and genocide in Europe and Africa. I mean, we don't have this kind of weird code of honor at all seemingly anymore.

[00:30:00] Ben Macintyre: You are right. I mean, that was a particularly extraordinary case, I have to say. I mean, one doesn't want to make the Germans all sound like cuddly, friendly, tearful fellows because they definitely weren't. In that particular case, that was one of the very early escapes. It was an escape of such bravery and ingenuity.

[00:30:18] I mean, this one character who went by the wonderful name of Pierre Mairesse-Lebrun, who was a cavalry officer or rather sort of handsome cavalry officer, literally vaulted over the fence and ran up the hill being shot at, and then stole a bicycle, and bicycled 250 miles to the Swiss border and managed to get across. The Germans were sort of so impressed by what he'd done. They couldn't help admiring him.

[00:30:44] I mean, I think if it had been anyone else or if the escape had not been quite such a feat, I don't think he would've had his rather smart Chanel suits returned to him in France. I just don't think that would've happened.

[00:30:57] Jordan Harbinger: I meant to tell you earlier, the one German guard who was the commander in the castle, you said he was an Anglofan, so he loved all things British and he organized an exchange student program from something called a gymnasium, which is essentially a high school in a city called Halal. He arranged a student exchange with a school in the United Kingdom by pure, ridiculous coincidence.

[00:31:19] That school, Johann Gottfried Herder in the former East Germany was where I did my exchange year in the '90s, and I was the first exchange student that they'd ever had, or so they told me. So that was my high school.

[00:31:30] Ben Macintyre: How fantastic. That's a wonderful coincidence. How interesting, I think some British students did go there before the war.

[00:31:38] Jordan Harbinger: That's what I was going to ask you. Yeah.

[00:31:39] Ben Macintyre: I think some of them did. We know for a fact that the character we're talking about is called Reinhold Eggers. He's one of my favorite characters in this book. I mean, he was a rather punctilious, rather fastidious kind of German, quite sort of serious and very serious minded, very cultured. But he was also a man of great sort of civilization and great sort of tact and politeness. And he had taught in Cheltenham in Britain before the war in 1933, and he couldn't ever quite get over the fact that all the people in Cheltenham had been very polite to him when he was there in 1933. Whereas the prisoners in Colditz were all incredibly rude to him all the time.

[00:32:16] He couldn't work out this kind of dissonance between the Brits he'd known back in Britain and the ones that was suddenly, he was having to try and keep inside them. But what a strange, strange coincidence. I bet you at the gymnasium. They would've remembered Reinhold Eggers. I mean, they would've remembered him.

[00:32:31] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I should have asked. I mean, the headmaster back then was also, as you might expect, a very stringent, sort of strict German man with a lot of rules who was very unhappy looking a lot of the time, and only towards the end was he just really, really amused that I could speak German. He never expected it to happen because I walked in not speaking a word of German. It was very funny for him, and he'd said in his whole career, in, in any memory he had, there were no exchange students there. But I figured if there was an exchange in the '30s before he was born, he might just not know about that. But I, yeah, it makes me wonder if there's a bust of Eggers somewhere in my old high school, somewhere in the basement there's a painting or something like that. I don't really know. I mean, it's a very old school.

[00:33:16] Ben Macintyre: I wouldn't be one bit surprised. I mean, there were considerable cultural exchanges between Britain and Germany in the run up to war.

[00:33:24] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:33:24] Ben Macintyre: For many people in Germany and in Britain, the fight with Germany came as an enormous surprise and a shock.Eggers remembered his time in Britain with great affection. In fact, one of the lucky breaks I had with this book was that when I was researching it, I contacted the grandson of one of the American prisoners in Colditz, a man who went by the wonderful name of Florimond Duke III, who was the kind of East Coast WASP who had ended up in Colditz.

[00:33:52] Jordan Harbinger: Wait. That was an American guy?

[00:33:53] Ben Macintyre: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:33:54] Jordan Harbinger: Florimond Duke III

[00:33:55] Ben Macintyre: Florimond Duke, believe it or not.

[00:33:57] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:33:57] Ben Macintyre: Absolutely. He'd been an advertising manager for Time Life before he'd fought in the first world, he'd been an ambulance driver. He was head of a sort of failed mission, a spy mission that attempted to send four American OSS officers, the forerunner of the CIA into Hungary on a secret mission. It failed spectacularly and poor old Florimond Duke was locked up with the rest of the Colditz prisoners.

[00:34:21] But his grandson revealed that he had a scrapbook that had been given to his grandfather by Reinhold Eggers, by this security officer. And it contained all the photographs that Reinhold Eggers had taken of different prisoners in Colditz and their escape attempts and their failed escape attempts. Eggers even persuaded these guys to reenact their escape attempts. So that he could take photographs of them and keep a historical record.

[00:34:47] And a lot of those photographs appear in the book. And it be, it was, but it also contains photographs of Eggers hiss own time in Britain as a school teacher. And these are other touching photographs of his former pupils, his former British pupils that are part of his scrapbook. I mean, it's the most amazing historical artifact.

[00:35:05] Jordan Harbinger: The internal divisions between the French and the Belgians and the Polish and the Brits were also quite funny. The British resent the French for not putting up a resistance, right? That's still a meme or a trope we have. It's like, oh, they surrender on day two. The French, they never fight. The Belgians were pissed off that everybody thought they were French and they're like, "We're not French. Okay? It's a different country. Okay."

[00:35:27] And then everyone liked the Yugoslavs because they were just this jovial bunch of guys. It's funny how these stereotypes almost still are fully in play, absolutely front and center inside this prison where you'd think like, "Okay, they'll get over it." Nope. Not even close.

[00:35:42] Ben Macintyre: Not even close. I mean, interestingly, while some of it was sort of jovial, sort of national banter, some of it was pretty sinister actually. I mean, there was an incident at the beginning of the Colditz experience when some anti-Semitic, French officers announced that they refused to be barracked, as it were with Jewish people.

[00:36:04] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:36:05] Ben Macintyre: Their own compatriots, French Jews. They said, we don't want to be with them. And these were people who had sort of, who were, you know, sympathetic to the Collaborationist regime in France, and they had adopted quite a lot of the Nazi attitudes. And that created a real division within Colditz because many of the other prisoners led by the British were absolutely scandalized that this kind of discrimination could be exercised by French officers against their own people. So there were distinctions between the nations that were just sort of national stereotype rivalries, but there were others that were extremely serious and based on real ideological and racial distinctions.

[00:36:47] Jordan Harbinger: That is kind of gross, especially imagine being in a Nazi prison. You're basically saying the same things as the Nazis that are outside fighting against your country. It's just, that's a weird take from those guys.

[00:36:59] Ben Macintyre: It's a weird take. And in a way it was, these were French officers who were pro-Nazi.

[00:37:03] Jordan Harbinger: Clearly, yeah.

[00:37:04] Ben Macintyre: As some French people were, you know, and I think it was also in a way, a sort of way of them trying to curry favor with the German authorities. I think they thought if they could show that they were in a way more Nazi than the Nazis, that that would help them in some way. It didn't, I mean, it didn't help them at all.

[00:37:19] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:37:19] Ben Macintyre: But it led to real conflict inside the castle.

[00:37:22] Jordan Harbinger: Some of the ways that they try to escape really are like cartoons. They steal a key while the guard is napping and they press it into a bar of soap and they make a copy of the key. I didn't even think that was a real thing. It sounds like something you'd seen a in a Disney cartoon or a movie, a bad movie.

[00:37:37] Ben Macintyre: Absolutely. I mean, I think that's, in a way, that's partly because. A lot of the escape stories that we got became familiar as part of sort of culture after the war were kind of borrowed from Colditz.

[00:37:47] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:37:48] Ben Macintyre: I mean, it became the kind of, you know, all that stuff about pressing keys into soaps and so on, that all happened in Colditz. It wasn't made up. I mean, those were real stories and they were new at the time, if you see what I mean.

[00:37:58] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:37:58] Ben Macintyre: To us, they now seem sort of cartoonish and slightly hackneyed, but people hadn't really done anything like that before. You know, there wasn't a sort of escape from prison culture, if you like. It became thoroughly embedded in the way that we saw the prison experience after the war.

[00:38:13] And you're absolutely right. I mean, some of them seem, I outlandish mad, even, I mean, but they were quite brave. I mean, certainly the bit sort of towards the latter end of the war, if you were still trying to escape from Colditz, you were taking your life in your hands. I mean, and many did not, not many, a number did not survive.

[00:38:29] And bear in mind that for all the attempts to escape from Colditz, only 16 people achieved what was called a home run. Only 16 people actually managed to get. And think of it that an escape is taking place once every three days, but only 16 men actually managed to get across the borders and back to their home countries. So the chances of success were very low, indeed.

[00:38:52] Jordan Harbinger: Some of the escape attempts were quite funny besides, of course, the one where they dressed up like the prison warden or the guard commander or whatever. There's this kilt wearing Scotsman, who's, I guess really short, so they sewed him inside a mattress and then just threw him away with the garbage. Tell me about this. That's ridiculous.

[00:39:08] Ben Macintyre: That's right. I mean, this was one of those sort of impromptu escapes when they spotted that old mattresses were being dragged out of an attic and put on the back of a cart, a horse and cart, and being taken down to the town dump effectively. And so just thinking on their feet, they, as you say, sewed this very small Scotsman into a mattress filled with kind of rotting straw and dumped him in the back of this cart. And sure enough, he was wheeled out through the prison gates.

[00:39:36] The only problem, as he rode afterwards, the only problem was that the straw inside it made him want to sneeze. So he spent most of the time as he was trying to escape, trying to stifle the sneezes that were caused. He got a long way actually, I mean, he got as far as Vienna before he was recaptured. It was one of the, one of the very early and, and, uh, very nearly a successful escape attempt.

[00:39:55] Jordan Harbinger: Didn't he give himself up though? He made his way to the American consulate, and I guess the guy there wouldn't help him, which is really disgusting actually. He just wouldn't help him get anywhere.

[00:40:04] Ben Macintyre: It's not a particularly noble moment. It has to be said. I mean, he, he was, by this point, he was very hungry and he'd been on the run for more than two weeks by this point. And he just thought that if he could get to the American consulate there, they might help him. And I'm afraid he just ran into one of those sort of bureaucrats who said, "No. You have to fend for yourself."

[00:40:23] Bear in mind, I mean, America was not in the war at this point. It wasn't as if the American was sort of turning in an ally. I think it was just one of those people who was sort of sticking unfairly, ruthlessly to the rules. I think had he got a different sort of bureaucrat on a different sort of day, he might well have been helped to escape. I think he was just hugely unlucky.

[00:40:43] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Ugh, such a ridiculous bout of bad luck after all that good luck a terrible bit of bad luck. And then there's this French officer who dressed up as a woman. What? How did they even, how did they get that idea? How did they get women's clothing? Did they make the clothes?

[00:40:59] Ben Macintyre: Yes, they sewed this entire outfit. The French spent months on kitting out this French lieutenant as a woman. And believe it or not, there is a photograph of him, which again, I found in Eggers' scrapbook, which shows him in drag in his full, and he's rather convincing.

[00:41:16] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, not convincing enough, apparently.

[00:41:17] Ben Macintyre: Not quite convincing enough. Well, that was the story of how he got rumbled is itself quite amusing. As I say, they'd spent a long time doing this and,women were not unknown in caldis. They were very rare because there were no women prisoners obviously. But the wives of senior German officers were sometimes seen in the castle courtyard grounds. There were women from the town who were brought up to do laundry and certain other do some of the cooking and so on. So there were women around. So it wasn't as if she was going to be completely extraordinary this figure, but I'm afraid it was the British who put paid to this escape attempt by accident, really.

[00:41:55] They spot as they were coming back from the exercise yard and they were allowed to exercise in a special yard under guard. They passed what appeared to them to be a German woman going the other way. And she dropped her watch as she was passing this line of British soldiers. And one of the British officers picked it up and ran after her and said, "Manfra, you've dropped your watch."

[00:42:15] At which point everybody suddenly realized this wasn't a woman at all. This was a man with a sort of homemade wig. And a kind of a sort of medium length skirt and a sensible pair of shoes on. So poor old, Louis Dere was the French officer was taken into custody immediately. The Germans were furious, of course. They found this whole thing to be ridiculous and extremely offensive.

[00:42:36] But I love the idea that Reinhold Eggers then managed to persuade this French officer to dress up in his kit again so that he could take a photograph of it.

[00:42:45] Jordan Harbinger: Like, all right, we have a drag band now, but first I really want to see you completely kitted out and get a photo of this for the record book, because it's so ridiculous.

[00:42:54] Ben Macintyre: Absolutely.

[00:42:54] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. That's really funny. I mean, if, if they had a better quality watch band, he might've been home by now.

[00:43:00] Ben Macintyre: Yeah, that's entirely right. I think that's true. I mean, you needed a lot of luck to get out of this prison. I mean, getting out of Colditz was hard enough, getting out of the castle was tricky enough. Getting out of Germany was even harder. Because you had to get across miles of country. You had to try and get to a neutral border and into Switzerland or try and get yourself on a boat to Sweden. You know, you needed to have papers, you needed to have disguises, you needed to have money, you needed maps, you needed compasses. There was a whole set of escape kit that, without which it was really hard to get out of Germany and it wasn't, you know, just getting beyond the castle walls was only the first stage.

[00:43:42] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest, Ben Macintyre. We'll be right back.

[00:43:47] This episode is sponsored in part by AG1. If you're a long time listener, you know I've been drinking AG1 for a long time. I'm practically green on the inside, I suppose by now. The founder is a huge health enthusiast. Friend of mine introduced me to it a long, long time ago. When I started drinking AG1 every day, you're drinking a vitamin drink, and at first you're like, okay, but then, you start to notice the gut stuff. I don't want to get into detail on that. Nobody needs that right now. Some of you are eating. That is in part because AG1 is a foundational nutrition supplement that supplements your body's universal needs, like gut optimization, stress management, immune support. Since 2010, AG1 has led the future of foundational nutrition continuously refining their formula to create a smarter, better way to elevate your baseline health. Even my friends in nursing who face those grueling 12 hour marathon sessions with hardly any time for a break, they are really into AG1 now. They often mention how it's been a game changer in keeping their nutrition on track despite their hectic schedules. Go figure, hospital cafeteria with 15-minute lunch break, not always doing the job.

[00:44:44] Jen Harbinger: AG1 is a supplement we trust to provide the support our body needs daily, and that's why they've been a partner for so long. If you want to take ownership of your health, it starts with AG1. Try a one and get a free one year supply of Vitamin D3 + K2 and five free AG1 travel packs with your first purchase. Go to drinkag1.com/jordan. That's drinkag1.com/jordan and check it out.

[00:45:04] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is sponsored in part by Jaspr. My friend Mike, he did home restoration after wildfire disasters, and he developed Jaspr. This is an awesome air purifier that goes in the house, Mike. We have a ton of them. Basically, Mike saw that regular home air purifiers, they just don't match the effectiveness of industrial models, but also industrial air purifiers look like crap kind of. So Jaspr's the best of both worlds. High efficiency of a commercial air purifier acquired operation looks like something you'd get at the Apple store. It's way better than a regular air purifier. You see these in medical offices, dental offices. I've got a few in my house. Like I said, they have an air quality monitor right on it, so you can really see how much more effective a Jaspr is than a regular air purifier. It adapts really quickly when somebody's cooking, when something gross is going on outside like there's a fire or something like that. We had an actual house fire across the street, and one of the ways I found out was because this thing kicked up so fast, even though all the doors and windows were closed. So if you're in a wildfire area, you got allergies, you're allergic to dust, pollen, got allergies, asthma, whatever it is, Jaspr is definitely going to be a good addition to the house. It's one of my favorite items in the house and I highly recommend it. Right now, Mike is offering a great deal just for our listeners. 25 percent off Jaspr Pro. You will not find that anywhere on the internet or anything like that. That's the model I have by the way. Just use code JORDAN at jaspr.co/jordan to claim the offer. Again, that's J-A-S-P-R.co/jordan.

[00:46:27] This episode is sponsored in part by Meater. Ah, the holiday is that magical time when we all indulge a little too much and hunt for the ideal gift. Speaking of which, there's a game changer for the festive season. The Meater, it sounds like a dating app for dudes, but it's not. It's actually a sleek, smart meat thermometer that will revolutionize your kitchen game. I know that you're thinking, I don't need that, but we have used this thing. It is kick ass and I don't mean we just got it. We've had one for years and we were like, they need to sponsor the show because this thing is amazing. Imagine never having to guess if your meat is perfectly cooked or worse finding out. It is turned into a charred dry ass brick. Meater keeps tabs on the temperature, even calculates how long it'll take and pings you when it's done because it hits you on your phone. You don't have to check it 87 times. It's amazing from everything for your oven grill smoker, even in an air fryer. We have tried all of those things. I put this nifty gadget to the test with our Thanksgiving Turkey. Smoked six hours to perfection without the constant back and forth checking. It syncs right up to your phone and iPad. So we are able to monitor the progress while doing a quick podcast recording because why not multitask and work throughout the holidays? So whether it's for yourself or a gift for that cooking enthusiast in your life meter is the way to go this holiday season.

[00:47:39] Jen Harbinger: Shop meater.com for the best kitchen tool out there and make the season stress free. That's M-E-A-T-E-R.com to check out their brand spanking new product.

[00:47:47] Jordan Harbinger: If you like this episode of the show, I invite you to do what other smart and considerate listeners do, which is take a moment and support our amazing sponsors. All of the deals, discount codes, and ways to support the show are all in one place over at jordanharbinger.com/deals. You can also search for any sponsor using the AI chatbot on the website at jordanharbinger.com/ai. Thank you for supporting those who support the show.

[00:48:09] Now, for the rest of my conversation with Ben Macintyre.

[00:48:13] You'd said something like 20 some odd tunnels were discovered, and that's just the tunneling ideas, right? The tunnel escape attempts, lots of escape equipment, maps, money, fake workers, overalls. How did they get the maps and the money? That's not something you can make because you don't know how to draw a map from memory. How did they get that stuff?

[00:48:32] Ben Macintyre: Well, this again, is one of the untold stories of Colditz is that there's a particular character called Christopher Clayton Hutton, who was actually, believe it or not, one of the models for Q in the James Bond stories, and he was a sort of mad inventor based in Britain and his job was to create escape kit for prisoners to try and get out of occupied Europe.

[00:48:56] He was able to create tiny maps that could be hidden inside other objects. He worked out ways to send money to the prison camps hidden inside gramophone records or playing cards or board games. The monopoly sets that were sent to Colditz, and they were sent as part of the Red Cross parcels or rather as sort of part of the charity parcels that were sent to imprisoned soldiers contained real money. It was real German money hidden inside the monopoly boxes.

[00:49:25] He was an extraordinary man. He was completely sort of lunatic really, but he was incredibly inventive and he managed to smuggle in hundreds of different forms of escape equipment. I mean, he even worked out how to hide a compass inside a bag of walnuts. One individual walnut in this bag of walnuts contained a compass. And again, there's a wonderful picture of it in the scrapbook that Eggers obtained.

[00:49:49] So Christopher Clayton Hutton is one of the great unsung heroes of the Second World War, in my view. I mean, he never fired a gun in anger, but there are other ways to fight a war. He was also helping downed air force pilots to get out, including a lot of Americans. So, you know, they would fly in the air with escape equipment already hidden in their boot heels or, you know, hidden in their buttons. So if they were shot down, they had a way to try to get out. One third of all the people who managed to escape from occupied Europe were carrying a map of some sort made by Christopher Clayton Hutton.

[00:50:22] Jordan Harbinger: That's really amazing because printing something small and then in a way that you can get it that's accessible but not obvious to somebody else, and then doing that at scales, a really big project.

[00:50:32] Ben Macintyre: Oh, it was very difficult. He did a lot of the maps were printed on mulberry leaf cotton, which has a particular quality. You can scramble it up until it's in a tiny ball, and yet it will reassume its original shape when you take it out and soak it.

[00:50:48] So he used to print maps on pieces of mulberry leaf cotton, which would then be scrunched up into tiny, tiny areas and then often hidden in boot heels or, you know, coat pockets or sewn into the lining of uniforms. He also, which I think was rather brilliant, he invented a way of putting a compass inside a coat button, which you could unscrew, but it unscrewed the wrong way. He had the thread on it going anti-clockwise instead of clockwise or the other way around. I can't remember. No clockwise. Instead of anti-clockwise on the impeccable theory that Germans were such a logical people, they would never imagine that you could unscrew something the wrong way.

[00:51:24] Jordan Harbinger: I mean, that's not a bad idea, right? Because if you're checking every button, you're probably turning it one way.

[00:51:29] Ben Macintyre: Yeah.

[00:51:30] Jordan Harbinger: Going to the next one, the next one, the next one, the next one. You're not thinking —

[00:51:32] Ben Macintyre: Why would you think someone would go to the trouble of creating a button that unscrewed the wrong way? You just wouldn't, you wouldn't be looking for it. I just, that's the kind of detail that Clut, as he was known, went in for.

[00:51:43] Jordan Harbinger: How long did the tunnels take to dig? I can't imagine. That's a quick process when you're trying to do it secretly.

[00:51:48] Ben Macintyre: Months. Months on end. I mean, the metro tunnel, the French one that I mentioned to build. And it was so elaborate and extensive that it went, it started in the clock tower of Colditz and went down the special sleeves that contained the mechanism of the clock tower.

[00:52:06] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:52:06] Ben Macintyre: Then it went down three floors into the basement. Then it went through the basement into solid rock, which they had to chip out very, very slowly. And then it went under the chapel where they cut out the, the ancient medieval beams holding up the chapel floor. They didn't cut them out completely, but they cut through them enough that an individual could wriggle underneath. And it was an astonishing thing. And all the spoil, all the earth and stone that was taken out, had to be laboriously, hauled up to the attics and hidden up there. And at one point they feared that the attic roof might actually collapse with the tonnage of sort of waste stuff that was being stored up there.

[00:52:46] Jordan Harbinger: It reminds me of Shawshank Redemption, where they go out to the prison yard and he shakes his leg and the dirt falls out and they just do that every day for months.

[00:52:53] Ben Macintyre: Absolutely. And that, of course, is taken from the great film, the Great Escape with Steve McQueen, which is also partly based on the Colditz experience. These things have a kind of a life that relates back in a strange way.

[00:53:05] Jordan Harbinger: It must be so demoralizing when you're spending five months building a tunnel and they find it. That's just got to be the worst day of your entire decade.

[00:53:15] Ben Macintyre: Well, that's right. I mean, and we, you know, we've, we've sort of talked about Colditz as if it was a sort of cheerful, fun place of sort of Jolly Jakes and so on. Actually, mental health in Colditz was very precarious. People suffered acute depression and the repeated failure of escape attempts. And bear in mind that the vast majority of them did fail. Did have a kind of cumulative effect on the mental health of people inside Colditz. Again, it's one of those subjects that historians after the war didn't really want to look at because Colditz was presented as if it was all a wonderful sort of story of courage and bravery and daring dude.

[00:53:52] And a lot of it was of course, but there's another story to Colditz and these were tough times for many of these prisoners, and the disappointment played a huge part in that. There were, I'm sorry to say, instances of people attempting to suicide. There were stories of mental breakdown. There were stories of people actually attempting to appear to have had mental breakdowns because that was one of the ways that you could get out of Colditz.

[00:54:15] Its possibly was that if you were considered to be, as they would've said, then insane, there was a possibility you would be repatriated. And there's one very moving story about a soldier who decided that he would attempt to get out by pretending to go mad, and in fact did suffer a complete nervous breakdown from which he never recovered. You know, he writes very movingly about this, that in pretending to be mentally disturbed, he ended up being mentally very ill indeed.

[00:54:43] Jordan Harbinger: Oh wow. He sort of method acted his way into it.

[00:54:46] Ben Macintyre: Yeah, and he did manage to get out. He was repatriated under this scheme, but he was put straight into a hospital and didn't emerge for a long time. He writes very movingly about, you know, not being able in the end to tell the difference between where his pretended madness ended and where real madness began.

[00:55:04] Jordan Harbinger: The way that they set themselves up over time is hard to imagine. You mentioned there's a part in which they got a radio. They somehow furnished an entire office with chairs and installation and a desk, and they would follow the war news. All in this secret room in prison, and again, this castle sounds like one of the worst places you should ever put a prison. It sounds like the prisoners knew the layout far better than most of the guards did. It's not hard to imagine the guards freezing their butts off outside guarding this giant place while the prisoners are inside in upholstered armchair listening to the BBC smoking, chatting and eating chocolate and stolen beer.

[00:55:39] Ben Macintyre: It would, the contrast wasn't quite as sort of acute as that. This was a pretty horrible place, Colditz. I mean, it was freezing cold. There wasn't enough to eat. But no, the radio gabit was extraordinary. It was the French, in fact, who managed to smuggle in the parts to build a secret radio, which operated in the attic, and they would pick up the BBC World Service. And so they were actually getting real news at a time when the Germans were not. They knew more about the progress of the war than their German guards.

[00:56:10] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:56:11] Ben Macintyre: It was quite extraordinary. And in secret for more than two years, they would listen to the nightly bulletin, cramped into this tiny little secret compartment they'd built in the attics. And then, so-called scribes would write out the news, and then they would read it to the different masses, to the different nationalities in Colditz. And it was a way of keeping morale up really.

[00:56:34] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:56:34] Ben Macintyre: It was a way of sort of making the prisoners feel less lonely, less isolated, less cut off from the rest of the war. So it served a sort psychological purpose as well as a moral one. The cleverer guards, including Reinhold Eggers, realized that the prisoners knew more about what was going on outside the castle than they did. Eggers was convinced there was a radio, but he never found it. In fact, years later, long after the castle was liberated and long after this story ended, they found the hidden radio set. They found it still in the attic where it had been left on the day that American forces came into Colditz to liberate it, and the, and the prisoners all left. It was still there.

[00:57:16] Jordan Harbinger: Wow. Wait, when did they find it?

[00:57:17] Ben Macintyre: They found it about five, or even later, five or six years after the liberation.

[00:57:22] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, wow.

[00:57:23] Ben Macintyre: They were doing some routine maintenance work in one of the attics, they began to take plaster off a wall and discovered there was this hidden compartment inside it. With the chairs and the table and the radio still sitting there intact.

[00:57:36] Jordan Harbinger: It's really incredible. That must've been such an exciting find for whoever found that. I mean, or they didn't care because they don't care about history. But that would be such an amazing, it's like finding a secret passage in your own home when you're a kid. Just the most exciting thing ever.

[00:57:48] Ben Macintyre: No, I think they were pretty excited when they discovered that. In fact, it made the sort of international news, the discovery of the radio set. But how ingenious, how clever, how brilliant to have worked out that they could build a radio from different spare parts. You know, they had to get the valves smuggled in, but the rest of it was made out of, I mean, I'm exaggerating slightly, but sort of bottle tops and bits of string. I mean, they really cobbled this thing together but it worked.

[00:58:11] Jordan Harbinger: What happened to Colditz now? When I was in Germany, I stayed in a youth hostel that was in a castle. But I assume there's a lot of those, right?

[00:58:18] Ben Macintyre: Yes. I mean, part of Colditz is now a youth hostel.

[00:58:21] Jordan Harbinger: Really?

[00:58:21] Ben Macintyre: You can actually stay in Colditz. Yeah. You can stay inside it. In fact, I lived there for quite a while searching this book.

[00:58:29] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:58:29] Ben Macintyre: I mean, Colditz is a huge castle, and the Germans are extraordinary in the way they preserve their history. It's been refurbished, it's kept up. There's a little museum in there about the wartime experience of Colditz. I mean, of course Colditz is much more famous in Britain and France and America and so on than it is in Germany.

[00:58:46] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:58:47] Ben Macintyre: I mean, the story is not well known in Germany. Because it's not something that is part of their, sort of, their national legend, if you like. And of course, as you know, that part of Germany became part of East Germany.

[00:58:58] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:58:58] Ben Macintyre: So it was behind the iron curtains.

[00:59:00] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, this is also in East Germany.

[00:59:02] Ben Macintyre: Yeah.

[00:59:02] Jordan Harbinger: Let me google this place because I'm curious.

[00:59:05] Ben Macintyre: Yeah.

[00:59:05] Jordan Harbinger: The place where I stayed was not, it didn't look like a castle. It was like a white house building.

[00:59:10] Ben Macintyre: Colditz is white now. It wasn't during the war, but it was painted white soon after. It's very castle like, let me put it that way. I mean, it's right perched on top of a hill.

[00:59:20] Jordan Harbinger: Oh my, yeah.

[00:59:20] Ben Macintyre: And I don't think it became a use hostel until quite late recently. I think that's only in the last 10 or 15 years.

[00:59:27] Jordan Harbinger: Okay. Yeah. Because this is in the '90s. It's hard for me to know what something looked like way back then, but —

[00:59:31] Ben Macintyre: But no, it was deep in East Germany. It's about 10 miles from Leipzig, so it's quite near the sort of eastern border of Germany. So during the communist years, it was really shuttered up and, and this aspect of cold its history was really forgotten by the local or they tried to forget it by, you know, the, the local German population. It wasn't much celebrated. Even today, the sort of guides to the Colditz castle are a little bemused by the passionate interest shown in this place by visiting British, French, Dutch, and others who turn up to have a look at it.

[01:00:04] Jordan Harbinger: They probably want to go more for the before World War II stuff than they do the during, I think that's pretty typical.

[01:00:11] Ben Macintyre: That is absolutely right. They'd much rather talk about the electors of Saxony from the 12th century than the Nazi use of the castle in the 20th.

[01:00:18] Jordan Harbinger: They probably don't love it when people are like, show me the room where they built the secret radio to hide from the Nazi guards. And they're like, oh, not, not one of these guys again.

[01:00:25] Ben Macintyre: Yeah, it's still a little bit sensitive.

[01:00:27] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[01:00:27] Ben Macintyre: It's a bit sensitive. But you know, the new generation of Germans are actually rather fascinated by their wartime history. You know, they are, it is not overlaid with the sort of shame of an earlier generation. There are increasing numbers of German visitors. And this book is actually going to be translated into German and published in Germany. So there is an interest in this sort of story these days.