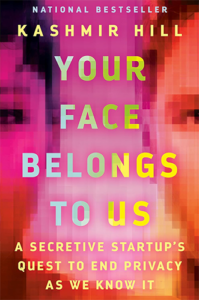

Are the benefits of facial recognition technology worth their societal cost? Your Face Belongs to Us author Kashmir Hill weighs the pros and cons here!

What We Discuss with Kashmir Hill:

- What is facial recognition technology, and how does it work?

- What are the positive use cases for facial recognition technology?

- How accurate is facial recognition technology, and what happens when it confidently misidentifies someone (or is used unethically by those with access to the keys)?

- Who is pushing for the proliferation of facial recognition technology, and what do they stand to gain from it?

- Is there a middle ground between the outright banning of facial recognition technology and completely allowing it to keep tabs on us in a world where privacy is a quaint relic of a bygone era?

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

Big Brother is watching you. Big Brother has always been watching you. But now Big Brother has technology on his side to watch you with eyes that see you unfailingly — except for when it does fail and rats you out for being someone you’re not to a government, law enforcement agency, or other entity that holds your life in its hands. What are the consequences of being an innocent doppelganger to someone who has reasons for not wanting to be found?

Big Brother is watching you. Big Brother has always been watching you. But now Big Brother has technology on his side to watch you with eyes that see you unfailingly — except for when it does fail and rats you out for being someone you’re not to a government, law enforcement agency, or other entity that holds your life in its hands. What are the consequences of being an innocent doppelganger to someone who has reasons for not wanting to be found?

On this episode, we’re joined by Kashmir Hill, journalist and author of Your Face Belongs to Us: A Secretive Startup’s Quest to End Privacy as We Know It. Here, we discuss how facial recognition technology can be used to make the world better, while sorting through the myriad ways in which it can be abused or misdirected to make the world worse. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. We appreciate your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini-course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

Subscribe to our once-a-week Wee Bit Wiser newsletter today and start filling your Wednesdays with wisdom!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- Nissan: Find out more at nissanusa.com or your local Nissan dealer

- US Bank: Apply for the US Bank Cash Plus Visa Signature Card at usbank.com/cashpluscard

- Progressive: Get a free online quote at progressive.com

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- The Adam and Dr. Drew Show: Listen here or wherever you find fine podcasts!

Miss the conversation we had with Tristan Harris, a former Google design ethicist, the primary subject of the acclaimed Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma, co-founder of The Center for Humane Technology, and co-host of the podcast Your Undivided Attention? Catch up with episode 533: Tristan Harris | Reclaiming Our Future with Humane Technology here!

Thanks, Kashmir Hill!

If you enjoyed this session with Kashmir Hill, let her know by clicking on the link below and sending her a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Kashmir Hill at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Your Face Belongs to Us: A Secretive Startup’s Quest to End Privacy as We Know It by Kashmir Hill | Amazon

- Kashmir Hill | Website

- Kashmir Hill | The New York Times

- Kashmir Hill | Threads

- Kashmir Hill | LinkedIn

- Kashmir Hill | Twitter

- What is Facial Recognition and How Does It Work? | Kaspersky

- Facial Recognition Technology: Current and Planned Uses by Federal Agencies | US GAO

- Face Recognition Technology | American Civil Liberties Union

- Facial Recognition | Clearview AI

- Face Recognition Search Engine and Reverse Image Search | PimEyes

- Reverse Image Search Face Recognition Search Engine | FaceCheck

- The Secretive Company That Might End Privacy as We Know It | The New York Times

- What We Learned About Clearview AI’s Hidden ‘Co-Founder’ | The New York Times

- National Institute of Standards and Technology

- Mark Zuckerberg Hides His Kids’ Faces on Social Media. Should You? | Business Insider

- Madison Square Garden Uses Facial Recognition to Ban Its Owner’s Enemies | The New York Times

- Racial Discrimination in Face Recognition Technology | Harvard University

- LOVEINT: How NSA Spies Snooped on Girlfriends, Lovers, and First Dates | Slate

- A Face Search Engine Anyone Can Use Is Alarmingly Accurate | The New York Times

- How a ‘Digital Peeping Tom’ Unmasked Porn Actors | Wired

- Facial Recognition Used to Strip Adult Industry Workers of Anonymity | Sophos News

- She Thought a Dark Moment in Her past Was Forgotten. Then She Scanned Her Face Online | KSBW

- Facial Recognition And Beyond: Venturing Inside China’s ‘Surveillance State’ | NPR

- Russia Illegally Used Facial Recognition to Arrest Protestor, Human Rights Court Rules | Politico

- Why an Illinois Law Is at the Center of Congress’ Debate on New Data Privacy Legislation | The Record

- The Birth of Spy Tech: From the ‘Detectifone’ to a Bugged Martini | Wired

- Documentary Exposes How the FBI Tried to Destroy MLK with Wiretaps, Blackmail | NPR

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) | The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute

- Do People Caught on Ring Cameras Have Privacy Rights? | Wired

- How Iran Is Pioneering a New Era of Oppression | The Christian Post

- China Drafts Rules for Facial Recognition Tech Amid Privacy Complaints | Al Jazeera

- Paul Mozur | The New York Times

- Laowhy86 | How the Chinese Social Credit Score System Works Part One | Jordan Harbinger

- Laowhy86 | How the Chinese Social Credit Score System Works Part Two | Jordan Harbinger

- Facial Recognition Spreads as Tool to Fight Shoplifting | The New York Times

- Which Stores Are Scanning Your Face? No One Knows. | The New York Times

- Facial Recognition Software Is Everywhere, with Few Legal Limits | Bloomberg Law

- How Facial Recognition Is Being Used in the Ukraine War | The New York Times

- 10 Pieces of Fashion You Can Wear to Confuse Facial Recognition | Gizmodo

- Can You Hide a Child’s Face From AI? | The New York Times

- Nina Schick | Deepfakes and the Coming Infocalypse | Jordan Harbinger

948: Kashmir Hill | Is Privacy Dead in the Age of Facial Recognition?

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: This episode of The Jordan Harbinger Show is brought to you by Nissan. Nissan SUVs have the capabilities to take your adventure to the next level. Learn more nissanusa.com.

[00:00:09] Special thanks to US Bank for sponsoring this episode of The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:13] Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:16] Kashmir Hill: Ultimately, any technology like this, it's about power. And so what worries me about facial recognition technology is that, there's a certain creepiness that we feel when we're online, right? That kind of feeling of being watched, being tracked, I just think it could all move into the real world with facial recognition technology, that our face would be this way of unlocking. This whole online dossier about us.

[00:00:44] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people and turn their wisdom into practical advice that you can use to impact your own life and those around you. Our mission is to help you become a better informed, more critical thinker through long form conversations with a variety of amazing folks, from spies to CEOs, athletes, authors, thinkers, performers, even the occasional Russian spy, gold smuggler, economic hitman, former jihadi, astronaut or tech luminary. And if you're new to the show or you want to tell your friends about the show, I suggest our episode starter packs. These are collections of our favorite episodes on persuasion and negotiation, China, psychology, geopolitics, disinformation and cyber warfare, crime and cults and more, that'll help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started.

[00:01:35] Today, Kashmir Hill is with me. We'll be doing a deep dive on facial recognition. Turns out, this surveillance technology has broad implications, not only for privacy, which as we know it might actually be dead entirely, to security, dating, law enforcement, and even warfare. This is a fascinating conversation with one of the few true experts on this emerging field, and we get into both the negatives and the positives of a future, in which your face might not belong to you. Here we go with Kashmir Hill.

[00:02:08] The facial recognition stuff is scary, not just because of how it can be misused, but actually because of how useful it is. So it's kind of like AI, right? It's so useful that I think we're going to run headlong into using it for everything with very little consideration of how this could go horribly wrong. What do you think about that?

[00:02:26] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, I think it's really complicated and there's some activists who say, "Hey, this is potentially so dangerous that we have to ban it entirely." But then you see all the positive use cases and you realize it's more nuanced than you thought.

[00:02:41] Jordan Harbinger: Right. This is not just like, "Hey, maybe people shouldn't have explosives in their house that they can buy unless they have tons of permits in their farmers and they need them for that. And then, even —" Right. This is like, "Do you want your phone to know when you're looking at it so that it unlocks? Yeah, I kind of do want that. I don't want to go back to the thumbprint thing. What about your computer? Yeah, that'd be great. What about instead of using passwords, we use facial recognition. Yeah, that sounds really convenient." And then it's like, "Well, if we ban that we can't do it." Of course, the legal system's going to have to adapt, and we'll talk about that in a little bit. But tell me about the companies that are doing this, primarily Clearview AI. What are they doing day to day?

[00:03:21] Kashmir Hill: So there are hundreds of companies that are selling facial recognition technology. What sets Clearview AI apart is that the company, a small little New York based startup, went out and scraped billions of photos from the public web from social media sites like Facebook and Instagram and LinkedI, and did it without anyone's consent. Their database now has 30 billion photos. And what happens is you can upload a photo of somebody you don't know to Clearview's app and it will pull up all the photos of them that appear on the internet. So you can find out their name, find their social media profiles and maybe even find photos of them that they don't even know are on the internet.

[00:04:01] Jordan Harbinger: I want to try this for myself. Will they let me do that? Probably not, right?

[00:04:05] Kashmir Hill: Clearview Limits use of its app to police and law enforcement agencies. But when I write in the book, what they accomplish is something other companies can do. So now there are public face search engines. You can go to a site called PimEyes, or a site called facecheck.id and you can do that. You can upload your face and see where else it appears on the internet. Those sites have smaller databases than Clearview AI. They're not quite as powerful a tool. But yeah, the dams are breaking, the cat is scratching its way out of the bag. We're really at a kind of scary moment right now where we could all lose our anonymity.

[00:04:44] Jordan Harbinger: So many law enforcement or professionals listen to this show. I probably can't get away with this, but I'm going to try anyway. If somebody out there has access to Clearview, can you run me through that and just email me what you saw, or I will call you and talk about this if you don't want to put it in writing.

[00:04:59] I'm so curious if it comes up with like, "Oh, someone scanned your high school yearbook and put it on a website and you don't even know that it's there and here's your photo from when you were 16." Or like, "Here's a driver's license database that got leaked and your face is in there." I'm so curious where it pops up. Because I already have thousands of photos online, but I'm not — that's not normal. And we'll get to the distinction between public figures and not, as well.

[00:05:27] Kashmir Hill: I've had Clearview searches run on me. At first, the company didn't want me to report on them and they put an alert on my face so that when police officers did run my face, people I was interviewing, the company would get an alert, basically, and call the police officers and tell them not to talk to me. But eventually, the company came around. I talked to the founder many times for the book and he's run these searches on me. And it brings up, you know, sometimes what you would expect, you know, headshots of me on the web that I know about. But then it's also brought up flicker photos from 15 years ago, photos of me at a concert in a crowd in the background of someone else's photo.

[00:06:04] Jordan Harbinger: Whoa.

[00:06:05] Kashmir Hill: Me, talking with a source at a public event in a photo I didn't realize was on the internet. There was this one photo of it with somebody standing in the foreground, somebody walking by in the background. And at first, I couldn't see myself in the photo until I recognized the jacket of the person walking by in the background. And I realized, "Wow, that's me." I bought that jacket in Tokyo. It's very unique.

[00:06:26] Jordan Harbinger: Whoa.

[00:06:27] Kashmir Hill: And it was this case where the computer was able to recognize me, where I couldn't even recognize myself.

[00:06:32] Jordan Harbinger: That's really something. I was not expecting that. I was expecting human eyes to do slightly better than the computer, but it doesn't seem like that's the case. And of course, the computer can do it a million times a second, and we can do it, you know, in a 30 second batch if we squint. But I still expected humans to go, "No, no, no. That is me. It's just blurry, but that's my purse. And those, I still have those shoes." But it seems like the computer can just be like, "No, here's your blurry face from a rave that you thought you were going to go to at age 40."

[00:07:00] Kashmir Hill: I mean, computers are better at this than us. They can remember billions of faces. At the same time, they do make mistakes. Mistakes have happened. People have been arrested for the crime of looking like someone else because they were identified by facial recognition technology. So I wouldn't want to give anyone the impression that this works a hundred percent accurately all the time. It can make mistakes. But wow, it has come so far. It can be very powerful.

[00:07:24] Jordan Harbinger: Can it also find people that just really look a lot like me, but aren't me? Did you see any photos of you're like, "That's definitely not me, but wow, that woman looks like me." That has to happen.

[00:07:33] Kashmir Hill: I have not seen doppelgangers that I can recall in a Clearview search. But it really, it depends on, there are all these settings that you can choose when you're doing a facial recognition program. And so, in procedurals, like on tv, whenever somebody runs a facial recognition match, it's like, "Here's a photo of somebody." And it just tells you who the person is.

[00:07:53] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:07:53] Kashmir Hill: But in reality, you get this whole page of results with lots of different photos, and the computer ranks it in terms of how confident they are that it's the same person. So if you like turn the confidency score down, you'll get more doppelgangers. You'll get more people where the computer thinks, "Oh, this is only 80 percent likely to be her." Et cetera.

[00:08:12] Jordan Harbinger: I would love to see somebody who looks 80 to 90 percent like me. I've had it happen once in my life when I was living in Israel. There was a guy who was like a VJ, he and I looked so much alike that I showed my mom a photo and she goes, "When did you get your eyebrow pierce?" And I'm like, "It's not me. It's a different guy. And it was really cool because he was kind of like a famous guy. He was on whatever MTV equivalent was in Israel. And so I'd go to the mall and 13-year-old girls would be like, "Oh my gosh." and then find out I spoke Hebrew like a toddler from three months of lessons. And yeah, they were disappointed. But it would be such an interesting test to run to see who looks like you, all around the world. Although it is amazing that it can sort of still tell. Because I guess, even if somebody looks like you, like the eyes are a little bit further apart, the ears are a little bit higher, lower on the head or tucked back more, the hairline's different or something like that. I don't know.

[00:09:06] Going back to the company, they're quite secretive or at least they were in the beginning, right? Didn't you try to walk there and the building didn't exist or something like that?

[00:09:15] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. When I first heard about Clearview AI, they had kind of shown up in a public records request as a tool that law enforcement might be using. And I went to their website, clearview.ai, and at the time, it didn't say anything about facial recognition technology, it just said artificial intelligence for a better world. And there was an address in Manhattan, and it was three blocks away from the New York Times where I work. And so I decided to walk over there. But when I got to where the building was supposed to be, it just wasn't there.

[00:09:43] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:09:43] Kashmir Hill: And I kept going back and forth, like I compare it in the book to Harry Potter. I was like, "Is there a platform I'm not seeing here?"

[00:09:49] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:09:49] Kashmir Hill: And you know, the company kind of had a hidden who was behind the company. People weren't responding to me. I saw that Peter Thiel might be one of the investors who was listed on this kind of startup tracking website as having invest in Clearview AI. When I reached out to a spokesperson, a spokesperson was like, "Oh, I don't think I've heard of that company before. I'll look into it." And then, I never heard from him again. And that kept happening with me every time I reached out to somebody, they just didn't want to talk about Clearview AI or having any ties to the company. And so, I had to go about it a different way, which is find police officers who would use the app.

[00:10:25] Jordan Harbinger: Wow. I get why they'd want to be secretive if you're in a startup and you're in a security industry. But it still sounds really dystopian when their slogan is artificial intelligence for a better world then the building's not there. And it's all about taking people's personal information without their consent. I mean, that's like you're a little on the nose for being a villain when you do that.

[00:10:45] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. The way that one of their investors put it to me was that they were in stealth mode, but this was a little unlike any stealth mode I've seen before. And I think they realized that what they did was very controversial, that they collected all these photos of us without our consent and that they were operating in kind of a legal gray zone and that people were going to be upset when they found out about it.

[00:11:09] Jordan Harbinger: Did they buy these photos from Facebook or were they just like, "Here's a bug where we can crawl every Facebook photo, slowly over time and they don't care or notice?"

[00:11:16] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, they were scraping photos and so that's creating these automated programs that go out there, and just look for photos of people and download them at mass. The founder, Hoan Ton-That, he's the kind of the technological mastermind behind the company. He described Venmo as being one of the first places that he was able to get these kinds of images because on venmo.com, they were showing in real time transactions that were happening on their network, for anybody who has their Venmo set to public, which you really should not do.

[00:11:46] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:11:46] Kashmir Hill: If your Venmo is set to public, change it right now. Make that private. Why are you broadcasting it?

[00:11:50] Jordan Harbinger: We know what you're doing when you put a snowman emoji next to an $80 deposit to one of your friends. We know what you're doing.

[00:11:58] Kashmir Hill: And so, Venmo would show all these transactions in real time like, "Jordan paid Kashmir." And Hoan told me that he would just send a scraper to the site every few seconds and it would download people's profile photos and a link to their profile. And he just sent it there every few seconds. He got a million faces this way. It was like a slot machine where every time he pulled the lever, faces spilled out. And so, he essentially did that all around the internet and hired people to scrape faces for him. And yeah, it was just like a great big face hunt on the internet and there are a lot of fish to catch there.

[00:12:33] Jordan Harbinger: That must've been kind of fun, though. I know it's sort of not a great thing to do, but it seems like a really fun thing to do — compile all these photos and make this product. It's interesting. It's exciting.

[00:12:42] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. And they were doing something that hadn't been done before that other companies hadn't been willing to do. And I think it was really exciting for them. At first, though, they were collecting all these faces, building this big facial recognition app, and they had a product in search of a customer. They didn't know, initially, who they would sell this to like who would buy this, who would pay for this?

[00:13:03] Jordan Harbinger: It seems obvious though, right? Because of course, the first thing, if you're really naive, you could say, "Oh, people are going to want a little Facebook app where they find other people that look like them. That's so fun." that's something I thought of probably in college. "Pretty soon you're going to be able to search for people that look like you. Isn't that going to be funny?" That was back when they had all those little games or like quizzes, you know, "Which Harry Potter character are you?" And you would answer stuff. I was like, "They're going to do this with pictures soon." but then of course, anybody with a security background at all is going to go, "Ah, well, I want to know who's walking into and out of my store." And if you've been reading the news, which you have for sure about China, they can just aim this at a giant outdoor crowd of people at a concert and be like, "There's three wanted fugitives here. Here's the guy that jaywalked on the way to the concert. Go and issue these people citations and then go arrest these other three triad gangsters who've been on on the run." I mean, that stuff is exciting, too.

[00:13:56] Let's talk about how it works and how well it works. Because it seems like it works super well given your anecdotal example, but how does the computer actually — what is it looking for? Do you know?

[00:14:08] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. So this is one of those technologies that was supercharged by machine learning or neural networks technology. The same —

[00:14:16] Jordan Harbinger: What is that?

[00:14:17] Kashmir Hill: It's the same kind of tech that has made ChatGPT so powerful. Essentially, the simple version of this is you can give a computer a bunch of data and it learns how to analyze it. And so that's what happened with facial recognition technology. It was like Facebook for example, had all these photos of people and we did the work for them, we tagged ourselves, you know? In a dark room, at a party, looking down, looking up, looking to the side, when we are young, when we are old, and they're able to give all those photos of a person to the computer and say like, "This is the same person. Learn this face." And that is how facial recognition technology now works. These computers know what to look for in a face at the pixel level to kind of see what makes a face unique, and they'll put it in a database with this long numerical code, a biometric identifier. And when you upload a photo of an unknown person, it generates that biometric identifier and then looks for anybody in its database that kind of has that same identifier or something similar to it. So it's essentially they've encoded our faces and now it can look through this database for a face with the same code.

[00:15:26] Jordan Harbinger: That's so interesting that the machine — so I think that's the key difference, right? The machine decides how it's going to search for or sort and what to look for. Because I'm thinking, "Okay, what am I doing if I'm programming this? Look at the nose and the distance from the eyes and how far apart the eyes are in the mouth and how wide it is." And the computer's like, "I've got this. Let me step back, old man. Let me handle this." And it figures out, "Aha! There's people that look a lot alike, but their chin size is always different, so I can use that as the defining thing when these are really close together. But when they're really far apart, I'm going to use the distance for their eye, their eyebrow is something that nobody —" It's like stuff we would just not think about, the computer can come up with. The machine learning, the correlations between things are always more and more bizarre. And I think, when they use this type of AI for medical research, they're, people I know are really excited about this, right? Because they can put in every study that comes out over the last 50 years and they'll say, "Hey, did you know that people who have their big toe is shorter than their second toe, they're more likely to get dementia later?" And it's like, well, no human would've. And it's going to be even more subtle than that. It's going to be like some gene allele that nobody even sees or tests for. Those people get dementia earlier unless they eat a lot of apples and they're going to be able to find that, because the machine will figure that out, whereas humanity never would on its own.

[00:16:43] Kashmir Hill: And the only problem with these kinds of technologies is that the scientists and engineers I talk to describe it as a black box. Like you don't actually know exactly what the machine is learning. And so with early, like really early facial recognition systems, they were actually looking at the backgrounds of the photos and they were identifying, "Oh, this person I see over and over again with the same background." and so they were learning that person was associated with that background. And we've seen that happen with some of the medical applications of AI where it kind of recognizes the font from a certain hospital as being distinct and it's kind of learning something about the font. So that's the only problem is when these systems go wrong or kind of make incorrect decisions, we can't always figure out who and why they did that because we don't know exactly how they work, which is disturbing.

[00:17:33] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. That could go wrong because then if there's a problem, you don't even know how to fix it.

[00:17:38] Kashmir Hill: Yes, exactly.

[00:17:40] Jordan Harbinger: How did they train the machines other than us tagging ourselves in photos? How does it learn now? Because I haven't tagged myself in a photo in a zillion years, and I don't post on Instagram. But I know there's tons of photos out there with me. Is it just the genie's out of the bottle, so now it's like, "Ah, we already have a thousand photos of Jordan. Any new one that comes up, we can just automatically tag him."?

[00:18:00] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. At this point, the algorithms have been trained on lots of data. They're very powerful. And now, they don't need to know who you are, they know now how to encode faces, and so they don't need to train on your face, specifically. They know how to identify a face. And so you can be new to them and they can still find other photos of you. They, you know, the systems are very good at that. Again, they still make mistakes. Sometimes this works better for some people than other people, certain groups of people. There's been bias problems facial recognition technology in the past. But at this point, the algorithms are trained. Yeah, they don't really need new training data.

[00:18:40] Jordan Harbinger: You are listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest, Kashmir Hill. We'll be right back.

[00:18:45] This episode is sponsored in part by Progressive. Most of you listening right now are probably multitasking. So while you're listening to me talk, you're probably also driving, cleaning, exercising, maybe doing some grocery shopping. But if you're not in some kind of moving vehicle, there's something else you could be doing right now. Getting an auto quote from Progressive Insurance. It's easy, and you could save money by doing it right from your phone. Drivers who save by switching to Progressive save nearly $750 on average. And auto customers qualify for an average of seven discounts. Discounts for having multiple vehicles on your policy, being a homeowner, and more. So just like your favorite podcast, Progressive will be with you twenty four seven, 365 days a year, so you're protected no matter what. Multitask right now. Quote your car insurance at progressive.com to join the over 28 million drivers who trust Progressive. Progressive casualty insurance company and affiliates. National average, 12 month savings of $744 by new customer surveyed to save with Progressive between June, 2022 and May, 2023. Potential savings will vary. Discounts not available in all states and situations.

[00:19:38] This episode is also sponsored by BetterHelp. We're often encouraged to reinvent ourselves with the New Year, but what if we take a moment to appreciate what we are already doing right? I'm sticking to parts of my routine that work well for me. My exercise routine, for instance, that is a non-negotiable four days a week. There's my Mandarin Chinese learning journey, which is a rewarding 11 year adventure where I should be way further ahead than I am. It's been a slow but steady climb, and this year I'm committed to ramping up my learning pace. Now, how about some therapy? It's more than a tool for navigating life's challenges, it's a way to acknowledge your strengths and enact real positive change. Therapy offers strategies for coping effectively in setting healthy boundaries, it's beneficial for anyone looking to hone their mental health. If therapy has been on your mind, but you find excuses to delay, consider this a gentle push to explore BetterHelp. It's an entirely online service that fits your schedule. You start with a questionnaire, get matched with a licensed therapist, and the flexibility to change therapists without extra cost is always there.

[00:20:30] Jen Harbinger: Celebrate the progress you've already made. Visit betterhelp.com/jordan today to get 10 percent off your first month. That's betterH-E-L-P.com/jordan.

[00:20:39] Jordan Harbinger: If you're wondering how I managed to book all these amazing thinkers and creators every week, it is because of my network. And now, I'm teaching you how to build your network for free, over at sixminutenetworking.com. This course is all about improving your relationship building skills. It's not cringey, it's down to earth. It's not going to make you or other people look or feel bad when you do. It's not salesy. It's not going to be one of those things. You need this skill if you're a teacher. You need the skill if you're in sales. You need this skill if you're a student looking for a job. I can't think of anybody who doesn't need to network. There's a lot of people who tell themselves they don't, but there's a lot of people who just leave that sort of proverbial money on the table and remain ignorant of the secret game that is being played around them. And look, I get it, it's time consuming. This takes a few minutes a day. Really, that's all it takes. And many of the guests on the show subscribe and contribute to the course. So come join us. You'll be in smart company where you belong. You can find the course again, for free at sixminutenetworking.com.

[00:21:32] Now, back to Kashmir Hill.

[00:21:36] What if it's a picture of me when I'm 20, and then it gets a picture of me when I'm 40, I look quite different. You can tell it's the same person, but when I show people photos of me when I was younger, I mean they're often like, "Oh wow, okay. That's you." but you looked way — and I just looked a lot different. Not just a different haircut, but like I really looked younger and better that's for sure. But there was a whole time 10 years ago where I was much bigger than I am now, and I looked very different. Can it tell that this is the young Jordan Harbinger or this is the older version of me? Can it tell or is it like, "Oh, this is two people."?

[00:22:11] Kashmir Hill: There's this big federal lab that tests all the algorithms. It's called the National Institute of Standards and Technology. And they have found that the accuracy of an algorithm can be affected by age, by face coverings and such. But it is the case that a lot of these algorithms do still work over time. I mentioned before, like Clearview AI is able to pull up photos of me from 15 years ago on Flicker where I weighed more. I actually hate those photos. I didn't know they were on the internet. It was my sister's friend took photos at a New Year's Eve party in 2005 or 2006 and she put them publicly on the internet. I didn't know and on I found out they were there. And I was like, "Ugh, I hate these pictures of myself like, please." I asked my sister, "Tell her to take them down or make them private." But yeah, I mean it's probably going to be pretty hard for a facial recognition system to match, you know, baby Jordan to Jordan now. But it might not be that hard to match you to yourself 5, 10, 15, even 20 years ago.

[00:23:12] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that's — matching a baby, I mean, the babies I know from having two of my own, when I look at their older photos, they're just like blobby, kinda look like old Chinese men. And now they look like completely different. I mean, my son looks almost exactly like me. And before, he just looked like this little sort of Buddha figure when he was like one or less. His face was very round and baby-ish and he's almost just stretched into a totally different person. So that's understandable. But most law enforcement agencies are probably not out there trying to figure out who babies are. Although, I can see in a missing person case why it would be really useful to see an aged version of a face that's more accurate than what we have now.

[00:23:55] Kashmir Hill: Right.

[00:23:56] Jordan Harbinger: And then can find that person like, "Hey, this person got kidnapped 10 years ago, and they're showing up in Madison Square Garden."

[00:24:03] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, sorry. On the baby thing, it just made me think about Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg. He posted on the 4th of July this photo of his family with his wife and his three daughters, and he put these like emoji stickers on the faces of his two older daughters because clearly, he wanted to protect their privacy. But then the baby face, he just left it exposed. And so there were people saying, "Oh, it doesn't care about the privacy of the baby." And I think it was just because, yeah, most babies look alike and facial recognition technology for that reason doesn't tend to work as well on babies.

[00:24:33] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, interesting. He might regret that when Facebook comes out with technology that can do that later. And he's screwed over the one, you know, the youngest kid, but, oh well.

[00:24:43] Kashmir Hill: But yes, it is getting used. Madison Square Garden is one of my favorite examples of what people call surveillance creep. Madison Square Garden originally installed facial recognition technology in 2018 for security threats. They're on top of Penn Station, major transit hub. They have these huge crowds that come to Madison Square Garden to, you know, see the Knicks, see the Rangers, see big concerts. And so they started using facial recognition technology. But then, in the last year, the owner, James Dolan realized that he could use the system to keep out his enemies, namely, lawyers who work at law firms that have suits against him, who he doesn't like because they cost him a lot of money. And so they went and scraped the lawyer's photos from their own websites, from their bio pages, and created this band list of thousands of lawyers. And when those people try to get into a game, or a Mariah Carey concert or a Rockette show at Radio City Music Hall, they get turned away. And I've actually seen this happen. I went there with a band lawyer. I bought tickets for a Rangers game. And all these thousands of people streaming in. We walked through the doors, put our bags on the security belt. By the time we picked them up, a security guard has approached us. He asked her for ID and she had to leave and she said, "Hey, I'm not working on any cases against Madison Square Garden." he says, "It doesn't matter. Your whole firm is banned." It was wild to see really how powerful it is and what businesses could do with it if they wanted to in terms of either tracking us as we walk in, knowing who we are, knowing everything that's know about us from the internet, how much we might have to spend or trying to keep out people they don't like, for whatever reason, whether it's your political views or you wrote a bad review of them on Google or Yelp.

[00:26:24] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like she could have just said, "Oh, I don't work there anymore."

[00:26:27] Kashmir Hill: I don't — Maybe she would have if I hadn't been with her, you know?

[00:26:31] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:26:31] Kashmir Hill: Writing about it for the New York Times, but I don't think it would matter. They could probably go to the website right then and see that she had a bio there.

[00:26:39] Jordan Harbinger: Like, "Oh, they didn't remove my bio photo. I don't work there anymore, no. I work in house at IKEA."

[00:26:43] Kashmir Hill: I asked some of the law firm partners. I was like, "Have you guys thought about not putting your photos on your bio pages in case more businesses start doing something like this?"

[00:26:51] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. It seems like they maybe thought about that and then they were like, "Nah, we'll just sue for some sort of discrimination and cost him way more money because two can play at this petty bullsh*t game that we're now playing." Because that's really what this is, right? Like, who cares if somebody goes to see Taylor Swift with their kids? This guy sounds like a prick.

[00:27:10] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, I mean, if the idea was ban the lawyers to dissuade litigation, that didn't exactly work out. A lot of the lawyers did too, just as you said.

[00:27:18] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Like even if you lose the suit, fine. I cost the guy $250,000 and now my other partner's going to do it, for different thing. I mean — Ah, man. Some of these people just can't help themselves. Are the algorithms just as good at detecting faces of all ethnicities? You mentioned there were bias issues, but is that what you mean by this?

[00:27:37] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. I mean, for a long time, a very troubling long time, back to 2000, 2001, these algorithms worked basically best on mostly white me and less well on everyone else. And the reason for that is that the people working on the technology were primarily white men. And they were making sure that it worked on them, worked on their friends. It was different with like algorithms from Asia for example, tend to work better on Asian people. It was about the training data.

[00:28:04] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I was going to say the training data and also the QA people probably are better at recognizing members of their own race versus other races.

[00:28:12] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. There is a same race effect. And so a lot of these facial recognition systems, it's a system working in concert with a human. Like usually the system says, "Here's some possibilities of who it might be." Then there's a human being who says, "Okay, I think this person is the most likely to be the match." So on the training data side, the vendors took the criticism and they said, "Okay, yeah, we need to make sure this works on everybody." and so they got more diverse training sets and they reduced that kind of occurrence of bias, and a lot of the algorithms have improved a lot there. But you still have a human being who ultimately has to look at this list of doppelganger, potentially.

[00:28:47] Jordan Harbinger: Mm-hmm.

[00:28:47] Kashmir Hill: And choose who the right person is. So you still have the possibility for bias there. And then, just even if it's perfect, you don't know when you're running a search like this, whether the person you're looking for is even in the database you're searching. There's many ways in which it can still go wrong.

[00:29:03] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like you mentioned only law enforcement has access to this among other, I guess, small groups of people, but there are still bad cops that stalk people or harass people. It seems like that could go horribly wrong. Especially, like imagine you're in a domestic abuse situation and your husband, your ex-husband, whatever, is a police officer, and now he can find you everywhere. That's really scary.

[00:29:26] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. There's actually a term for this because it does happen so often with surveillance technologies. — "LOVEINT" or "Love Intelligence".

[00:29:34] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, I see.

[00:29:34] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. And this is when police or intelligence officials kind of misuse surveillance tools where they're like searching databases for partners and loved ones. And you know what happens a lot? Police officers I've talked to, they think this is a very powerful technology. They want to use it. They want to use it responsibly so that they can keep access to it. And so they say they have controls in place to make sure that officers aren't kind of just like willy-nilly, searching whoever they want. They're supposed to tag it with a case number, et cetera, that they review the logs. But again, that's just with Clearview AI.

[00:30:09] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:30:09] Kashmir Hill: There are other face search engines out there that anyone can use. So there's one called PimEyes, and I write in the book about this guy who — he actually came to me and he wanted to confess how he was using PimEyes because he thought it was wrong. He wanted lawmakers to know so that they would hopefully regulate it out of existence. But he essentially had a porn addiction and a privacy kink where when you would see women in pornographic films, he would, you know, they're using pseudonyms, they're trying to kind of keep their identities hidden because there's so much stigma around that kind of sex work. But he would search them on PimEyes, find out the real names, find their high school photos and basically compile this big dossier of this is who they really are. And eventually, he got sick of doing that and he went through his Facebook friends list and would just look for his friends' faces to see if they had any risque photos online. And he found them, he found them on revenge porn sites.

[00:31:06] Jordan Harbinger: Oh man.

[00:31:06] Kashmir Hill: Somebody who had been in a naked bike ride. All these photos that had been safely obscure because they weren't attached to these women's names. But once the internet was reorganized around our faces, all of a sudden, he could find it.

[00:31:17] Jordan Harbinger: I went to the University of Michigan and we had this thing called the Naked Mile. And it was basically, you would just run through campus naked and tons of people did it. And every year they were like, "Stop doing this." And we're like, "Ah, what a bunch of prudes." And they kept saying, photos of this are going to end up in places. And I remember being like, "Come on man. So somebody takes a photo of me wearing sunglasses in a hat, biking naked or running naked through campus. Who cares? No one's going to find it." And now it's like, "Oh actually technology evolves over the last two decades. Now there's the guy we're interviewing for this job, wearing a fluorescent orange hat and sunglasses, and literally nothing else running through the quad." And it's like, maybe people just go, "Oh, well we all did stupid stuff in college." But maybe they also do something really nasty with it. And the revenge porn stuff is terrifying. For people who don't know what revenge porn is, how would you explain what this is?

[00:32:12] Kashmir Hill: So they're non-consensual, intimate images. So it's basically you are in a relationship, you shared intimate photos of yourself, selfies, and then relationship goes south and the person you shared the images with puts them on the public internet to punish you and embarrass you.

[00:32:27] Jordan Harbinger: And it can be really bad. Sometimes people film each other without their consent. And then there was a website that somebody eventually, I won't even give the name, but somebody bought it and shut it down. They spent millions of dollars on it because it was this huge revenge porn site, and people's lives were essentially ruined by this. You get some 16-year-old girl on there that's now wants to kill herself because her stupid ex-boyfriend put all these videos up online. So this makes it even worse because at least then, it was like that guy had to share it with her friends and then that was the worst of it. And then a few years later, she could be free of this, maybe move away something. Now this stuff follows you. You can move to the jungles of Cambodia and somebody can find you in your photos on a site like this using this technology. That's really creepy that this guy searched for adult film stars and then went to find them elsewhere. Is that stalking if you don't go after the person? It's still so invasive and weird to me to do that.

[00:33:21] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. He considered it. He said, "I'm just a digital peeping Tom. I'm not acting on this." But you could certainly imagine the way, just how nefarious it could be. And just this idea, I mean, what you're saying that the naked run, there's so many times in which we rely on being anonymous in a crowd, being surrounded by strangers, not having all these moments just follow us forever. And that's my great fear with facial recognition technology, that you couldn't be in a restaurant having a sensitive conversation without worrying that somebody around you who's a stranger to you, might overhear something juicy. And then, they take your photo and all of a sudden they know who you are.

[00:34:02] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:34:02] Kashmir Hill: And they can understand the context of the conversation. Just all these different moments. Buying something sensitive in a pharmacy, walking out of a Planned Parenthood. Just all these moments where somebody could take a photo of you. Having a bad day on the subway and you're rude to somebody. They take your photo, they know who you are. Just so many things could haunt you in this new world if we are just identifiable all the time by each other — companies, governments.

[00:34:26] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. People shouldn't have to take Moscow 1984 CIA precautions to meet with somebody and have a sensitive conversation. It sounds like I'm exaggerating. But even now, of course, or especially now, you can't meet in public because then they see this person who's supposed to be an NGO worker at the US Embassy meeting with this other person and it's like, "Oh, well what are you meeting with them for?" And you met him in another place, earlier. And we just asked you and you said you didn't know them or you said you knew them under these circumstances, but they're not. And so now they have to, and they probably always have, had to meet in these very like dead drop type things. I mean, dropping a note in a tree stump that's in code, it's like they still do some equivalent of this even with digital communication because of stuff like this. And as I said before, with domestic violence or people who are stalked, this is just an absolute nightmare for them, especially.

[00:35:15] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, it makes you have to really rethink anytime you're photographed, anytime you're on camera.

[00:35:21] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:35:21] Kashmir Hill: And certainly anything you post publicly on the web.

[00:35:24] Jordan Harbinger: Authoritarian governments could do the even worse with this, right? We're talking about users now that have limited resources. But we mentioned before China, I'm thinking North Korea, Iran, Canada, maybe not Canada. Well, who knows? I mean, the United States is. Governments are going to misuse this, I think is where I'm going with this. And governments that are going to misuse this, it's either going to happen sort of by mission creep/accident, US, the West Canada, whatever. But there are countries that are going to do this because it controls the population like Iran and North Korea.

[00:35:55] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. I mean, some countries have deployed facial recognition technology far more widely than we have in the US. So in Moscow, they've deployed facial recognition algorithms on surveillance cameras, so they get real time kind of alerts when they're looking for wanted criminals or missing persons. I've heard about people who get stopped because they have that doppelganger problem where the system keeps saying that they're this wanted criminal. They get stopped, they have to show id, I'm not that person.

[00:36:23] Jordan Harbinger: Oh man.

[00:36:23] Kashmir Hill: In China, during the protest in Hong Kong, the protestors would scale the camera poles and try to paint over them because facial recognition was being used to identify them. It's used there to automatically ticket people for jaywalking, to name and shame people who wear pajamas in public in this one city.

[00:36:43] Jordan Harbinger: Okay.

[00:36:44] Kashmir Hill: And in a public restroom in Beijing, they were having problems with toilet paper.

[00:36:49] Jordan Harbinger: Toilet paper. Yeah, I heard about this.

[00:36:51] Kashmir Hill: So installed facial recognition technology, they have to look at the camera, dispenses a certain amount of toilet paper, and if you want more, you have to wait like seven minutes and look into the camera again. This is this problem of, once you start putting the infrastructure in place, you, maybe the intention originally is for safety and security purposes, but then you realize, "Oh, it's also good for all these other purposes." And suddenly, you have this very controlled society where you're afraid to —

[00:37:18] Jordan Harbinger: Poop in public.

[00:37:18] Kashmir Hill: Yeah.

[00:37:20] Jordan Harbinger: Like I'm willing to use my face to unlock my phone, but when you're asking me to unlock the TP role, I'm already in dire straits. I'm on a street in Beijing using a public restroom. I obviously need more than eight squares of toilet paper. Bring your own TP if you ever go to Beijing.

[00:37:35] Kashmir Hill: Yeah.

[00:37:35] Jordan Harbinger: That's the takeaway from this podcast.

[00:37:37] Kashmir Hill: BYTP.

[00:37:38] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. In the US, we have to look for corruption and other issues where this could go horribly wrong, right? Our legal system's going to have to change to accommodate this. Do you have any thoughts on what might be necessary as far as changes in the line? I know you're not an attorney, but I'm curious if you have thought about this.

[00:37:54] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. I'm a journalist, so I try not to give policy recommendations. But I can tell you what I have seen happening.

[00:37:59] Jordan Harbinger: Sure.

[00:38:00] Kashmir Hill: And the reaction has been really different in Europe and Australia and Canada, as you mentioned, than in the US. And those countries, when they found out about Clearview AI, said, "Hey, this company violates our privacy laws. You can't just collect photos of people and the sensitive biometric information and put them in a database without their consent. You can't do that here." And many jurisdictions find Clearview AI, they basically kick the company out of their countries. So that's a really different reaction to this, right? Whereas in the US, we just don't have a national law like that, that gives us that kind of control over our personal information. There are some rare exceptions, like Illinois happens to have the state law that says you can't use people's voice print, face print, fingerprints without their consent or you have to pay a big fine if you're a company. And so if you live in Illinois, you have more protections over your face. But for most of the rest of us, that doesn't exist. So I think that's one thing we could think about is, should these companies be allowed to make these databases or not? Should we have kind of control over these sensitive pieces of information? If we are going to have it out there, how should it be used? Should Madison Square Garden be able to ban lawyers?

[00:39:11] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:39:12] Kashmir Hill: They can't. Madison Square Garden actually owns a theater in Chicago and they can't use facial recognition technology to keep the lawyers out there because it would violate this law that Illinois has.

[00:39:21] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:39:21] Kashmir Hill: They'd have to get the lawyer's consent to ban them.

[00:39:24] Jordan Harbinger: Is surveillance technology, like it's always misused. Even when the best of intentions, even when we start off with the best of intentions. Didn't the FBI, or I might be getting this wrong. Somebody tried to get Martin Luther King to sort of like back off his stuff, or even wanted him to kill himself because of blackmail. Am I imagining this or is this a thing that happened?

[00:39:44] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, there was this time in the 1950s, 1960s when they called it the electronic listening invasion. And it was a time when there were all these little bugs, wiretap equipment and yeah, it was widely used to crack down on crime, but also to monitor dissidents. And so I think they bugged Martin Luther King Junior's hotel room, his office. They just had these listening devices everywhere. They recorded evidence of an extramarital affair, sent a tape to him and his wife and kind of, yeah, I mean they were encouraging him to commit suicide, to step down from the movement. So yeah, that was a time in which we were seeing surveillance technologies misused. And that was actually a time when people were freaking out in general, that they wouldn't be able to have private conversations anymore because they were so worried about these new technologies. And we did react back then, we passed laws that said that you can't just be recording people secretly without consent, that the government needed to go through certain steps to be able to use that kind of technology. And it's the reason why the surveillance cameras that are all over the United States are only recording our images and not our conversations. So that's where I'm hopeful. I think that there's been moments in time before where we said, "We want a certain kind of privacy to exist in the world and we're going to pass laws to create the future we want and not just let the technology dictate it for us."

[00:41:10] Jordan Harbinger: Huh. That's interesting. Then I wonder why my ring doorbell can do audio and video. Is it just people consent to being recorded because they're on my property, at that point? I wonder how that works.

[00:41:19] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, it is a little legally complicated. I've wondered about that because it is recording audio. I don't know how much it catches, how far away they are. But I know that people who do have ring doorbells are encouraged to have kind of signage that says, "Hey, you're being recorded here and audio's being recorded." I think you're actually supposed to notify people.

[00:41:39] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Because otherwise, surveillance cameras — I mean, you're right. They don't have audio. I never really noticed that. And yet, some of the stuff you buy for your house absolutely does. Like all my cameras here on my property, they have audio and I'm sure they send it directly to China or wherever the servers are located. But yeah, they have audio and video and that's one reason why they're not in rooms where people might change or something.

[00:42:04] Kashmir Hill: And I think it's a little different when it's your house, it's your property. Whereas most surveillance cameras are kind of in public spaces. But yes, you know, when it's outside, you might want to put up a sign saying, "You're being recorded here."

[00:42:17] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:42:17] Kashmir Hill: If nothing else, it will probably deter bad behavior.

[00:42:22] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest, Kashmir Hill. We'll be right back.

[00:42:27] This episode of The Jordan Harbinger Show is brought to you by Nissan. Ever wondered what's around that next corner, or what happens when you push further? Nissan SUVs have the capabilities to take your adventure to the next level. As my listeners know, I get a lot of joy on this show talking about what's next, dreaming big, pushing yourself further. That's why I'm excited once again to partner with Nissan because Nissan celebrates adventurers everywhere. Whether that next adventure for you is a cross country road trip or just driving yourself 10 minutes down the road to try that local rock climbing gym, Nissan is there to support you as you chase your dreams. So take a Nissan Rogue, Nissan Pathfinder, or Nissan Armada and go find your next big adventure. With the 2024 Nissan Rogue, the class exclusive Google Built-in, is your always updating assistant to call on for almost anything. No need to connect your phone as Google Assistant, Google Maps, and Google Play Store are built right into the 12.3 inch HD touchscreen infotainment system of the 2024 Nissan Rogue. So thanks again to Nissan for sponsoring this episode of The Jordan Harbinger Show and for the reminder to find your next big adventure and enjoy the ride along the way. Learn more at nissanusa.com.

[00:43:26] This episode is brought to you in part by US Bank. Seems like there's a credit card for everything these days, right?

[00:43:31] Food cards, cards for travel, cards for rare stamp collecting. For me, I don't know what I'm going to be spending money on from one minute to the next, but wouldn't you know it, US Bank has a card for people like me. Check out the US Bank Cash Plus Visa Signature card. With this card, you get up to 5 percent cash back on two categories that you choose every quarter. The great thing is the earning doesn't stop there. Even after you choose your first two earning categories, you also earn 2 percent back on one everyday category you choose each quarter like gas stations and EV charging stations or grocery stores or restaurants, and you still earn 1 percent on everything else. Apply today at usbank.com/cashpluscard. All that already sounds good, but this card just keeps earning with a $200 rewards bonus after spending a thousand dollars in eligible purchases within the first 120 days of account opening. If you like choosing how your card earns, apply at usbank.com/cashpluscard. Limited time offer. The creditor and issuer of this card is US Bank National Association, pursuant to a license from Visa, USA Inc. Some restrictions may apply.

[00:44:27] If you like this episode of the show, I invite you to do what other smart and considerate listeners do, which is take a moment and support our sponsors. All the deals, discount codes and ways to support the show are at jordanharbinger.com/deals. And if you can't remember the name of a sponsor or you can't find the code, just email me. I'm jordan@jordanharbinger.com. I'd be more than happy to surface that code for you. Yes, it is that important. Thank you so much for supporting those who support the show.

[00:44:52] Now for the rest of my conversation with Kashmir Hill.

[00:44:57] In repressive regimes, I'm thinking like Iran, what if you're secretly a Christian, right? They could figure out who you are by your movement pattern, and if they ever caught you or a glimpse of you going into a secret church or something like that, you could be in real trouble. And I bring up this weirdly specific example because I had an Uber driver that was from Iran. And I was like, "Oh, tell me how you ended up here." and it turns out, he was basically a secret Christian. His church was literally underground in a basement, somewhere. And the Christian community in the United States helped him escape because they were being prosecuted and persecuted by the government. It was apparently illegal to do what they were doing, to go and be Christian in a basement, I guess. I don't know. And he was still so afraid of the Iranian regime, he wouldn't even tell me more details. He changed the subject. I asked another question, he's like, "Hey, I don't, I don't want to talk about this." And so, regimes like that having even more power over its population. In real time, the ability to identify that, that's really terrifying. Especially, what if I'm an Iranian secret police officer and I want information on Iranians in the US? I could use Clearview and find out where these people are hiding or where they're living, and I could use it to harass them. And it wouldn't be hard for me to get an account saying I'm a police officer in Boise, Idaho. I mean, this is an intelligence agency.

[00:46:15] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, Clearview has said that they do not want to sell their technology to authoritarian regimes. But the problem is, it is becoming easier and easier to create technologies like this that there probably is some company or home brewed company or the government could create something like this. It really is a potentially powerful weapon for control.

[00:46:40] Jordan Harbinger: Like you said, the scary part of this is even if we end up — let's say we get Clearview and they're great actors, and maybe they are, and then it's like, "Okay, fine." Well, an authoritarian regime just builds their own version of this. It's probably not that hard to scrape photos from social media websites or buy them in bulk from somewhere, or even have your state run hacking intelligence agency, get millions or billions of them for specific groups. It might be slow, it might be less efficient, it might be slightly less accurate, but if you're just trying to get everybody in Turkmenistan or North Korea into a database and make it searchable, it can't be that hard with modern technology to do that if you have the resources.

[00:47:20] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, I think we're going to see a world where your face has different amounts of privacy, depending on where you live. One interesting thing we've seen happen in China is that they now have red list. They have blacklists for these are wanted people, these are people to monitor. And then there's red lists for people who don't want to be seen by the cameras, who are authorities, who know about this surveillance infrastructure and want to be able to move through the world and not be tracked.

[00:47:52] Jordan Harbinger: Wow.

[00:47:52] Kashmir Hill: And so, I think that's very interesting to see this privacy becoming a luxury good that your benefit for being in power is that you're not seen by the cameras.

[00:48:02] Jordan Harbinger: So basically, how does this work in practice? So the camera sees you says, "Oh, that's a guy that's on the red list." Suddenly your name doesn't show up. And the people who came and went, suddenly your photo's not available. Maybe it auto blurs you from the security agents that are looking at this later on and you're just anonymous. But I assume that's not something that you get unless you are a CCP official at a decent level.

[00:48:25] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, I think so. And the way one of my colleagues is in China or has done a lot of reporting on surveillance in China, Paul Mozur at the New York Times. And he said that, we think of China as kind of this monolith, but that the systems of surveillance are very localized and so it's happening like city by city, it's very different. You know how the local authorities are using it. And you know, there's basically a bunch of little sheriffs that have their own kind of surveillance systems and so it looks different depending on where you live, for now. I don't know. At one point, that all gets locked in and intertwined.

[00:48:59] Jordan Harbinger: Sure, yeah. If something tests well, like the social credit score system is not all over China. But I have some teachers that have it in their town and other teachers that have never seen it. And yeah, it's quite interesting because of course, yeah, you're right. You think it's in China. What, does that mean it's in Shanghai? Does that mean it's in rural Xinjiang, or does that mean it's only in Xinjiang and not anywhere else in the country? Or is it being tested in a small province that you've never heard of or been to, to see if it actually works, or if it causes more trouble than it helps solve? Trying to ban this kind of tech, it's impossible. It's like trying to ban alcohol, right? The technology exists, you can't put the genie back in the bottle. I don't think people are ready for this. This metaphor might not hold up, but I'll give it a shot. This tech turns everyone into a public figure. Now, I'm not really famous. I'm only barely scratching the qualifications of public figure by the loosest of definitions, right? But I know enough from my own experience of what might be called internet fame, if you can call it that. Most people, they don't want this at all, and many people won't be able to handle the consequences of this. What I mean is that, you said this earlier, most people like being anonymous at some level. Not so they can shoplift and get away with it, but because most people, it just creeps them out to know that somebody knows all the places they've been to in a whole week, how long they spent there, what they did when they were inside. For someone like me, it's fine in many ways. I like it when somebody recognizes me in public and says hi, and I've never met them before. And they know a ton about my life because of the parasocial relationship that we have on this podcast. But this is worse. This is a system tracking your every move, knowing all about you. And the only time it comes up to say hi is when you get a citation in the mail for jaywalking or you get some coupons from the lingerie story that you thought nobody knew you even shopped at or whatever. And that's just the commercial use of this system, right? Not the national security implications of this stuff.

[00:50:52] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, I think ultimately, any technology like this, it's about power and the more that you know about someone else, the more power you potentially have over them. And so, what worries me about facial recognition technology is that there's a certain creepiness that we feel when we're online, right? When you're going to a website and you know that there's all these cookies on your computer and basically you're transmitting who you are. They're tracking that you've been on their website, they know you've been on other websites, you can tell from the ads. That kind of feeling of being watched, being tracked, I just think it could all move into the real world with facial recognition technology, that our face would be this way of unlocking this whole online dossier about us. And yeah, there might be benefits to it, it could be great in some ways, but I think in other ways it'll be very chilling and kind of make you paranoid for a reason that all the time, somebody might be looking at you because they know that you're Jordan and they're like, wondering what you're going to pick up in the grocery store or they saw that you bumped into somebody on the subway and you didn't say you're sorry. Just all these little tiny ways in much larger ways that we could be surveilled and controlled is alarming.

[00:52:05] Jordan Harbinger: I went out to dinner with a very sort of, well-known fitness influencer, and the waiter was like, "Whoa, are you so and so?" And he is like, "Yeah." And he is like, "What are you going to order?" And I'm like, "Oh, this is hilarious. You have to order something healthy now. We were going to get a pizza, you can't get this pizza now. I'm eating a pizza, you are getting Brussels sprouts or something." And he is like, "Yeah, I kind of want wine and the cheesy flatbread." And the guy was like, "Really?" And he is like, "Dude, I'm celebrating something. I'm here with my friend." Like it was so funny because I just thought you are so painted into a corner with your brand. That guy's going to take a snapshot of you eating cheesy flatbread and be like, "He's a fraud." You can't eat this in public. You're screwed. The price of fame.

[00:52:47] Kashmir Hill: The price of fame.

[00:52:49] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like this will be tremendously convenient, right? You can go shopping and walk out with stuff and it'll be like, "Oh, we just billed this to your Amazon account." I think they're already working on how that works.

[00:52:57] Kashmir Hill: They've got the palm print, right? Like I went to a Whole Foods, outside of San Francisco and they're trying to collect the palm so you could just like pay with your palm. I asked the clerk, I was like, "How many people have actually signed up for this?" He is like, "Very few." It's not actually that appealing.

[00:53:13] Jordan Harbinger: It's invasive and also it's kind of gross because you're touching something that everybody else is touching with their hand, which like a post covid era, not super advisable, I guess, for a lot of folks. And also, the convenience of that versus just paying with your card is marginal or paying with your phone is marginal. Facial recognition where you just push the cart straight out the door to your car and it's like, "Here's everything that was in the cart because it has RFID tags or something.", that is convenient. And the security stuff is great. The stores could ban shoplifters. Hopefully not the wrong people but the right people.

[00:53:44] Kashmir Hill: Yeah. That's certainly happening. That's happening already. Yeah.

[00:53:47] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, it is? That's great.

[00:53:48] Kashmir Hill: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Here in New York, grocery stores, Macey's has facial recognition technology to keep people out. That's happening and hopefully again, you don't have a bad doppelganger who shoplifts?

[00:53:57] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, geez. I guess then you'd have to handle that with corporate and they'd have to figure something else out. I mean, they want to keep you as a customer, somehow. I'm sure there's a policy for that. Hotels could greet guests by name, I think that's something you wrote about in the book. That's great. Or even maybe I don't need a hotel key. Maybe when I get to my hotel room door, it just opens because it sees me. That kind of stuff would be cool.

[00:54:16] Kashmir Hill: So this actually happened to me. I was on book tour, my publisher booked me at Four Seasons in St. Louis and I had a super early morning flight, like I had to leave at 5:30 AM. And so I arrived, I just felt really bedraggled and I just didn't look good and I walk up to the hotel and they greeted me. They're like, "Oh, Kashmir Hill of the New York Times." And you know, it was good customer service. They weren't using facial recognition technology, I don't know how they did it. But I was like, "I don't want to be recognized right now. I look bad, like I just want to be anonymous." And so —

[00:54:48] Jordan Harbinger: That's really funny.

[00:54:49] Kashmir Hill: It's not always good to be recognized.

[00:54:51] Jordan Harbinger: That's just like the fitness thing. It's like, "I thought being famous would be fun until I went outside in pajamas to get something from 7-Eleven." Yeah, that's how that works. You got to take the good with the bad. So we can't stop this, but what can we do? What sort of world are we headed for? Because this sort of tech, this sounds hyperbolic, but it basically ends privacy as we know It, doesn't it?

[00:55:13] Kashmir Hill: I think it does definitely end anonymity as we know it, and I do think that we can stop it. And I just don't know exactly what that looks like. Maybe we decide, police using this is a good thing within reason. And if they're doing proper investigation, it's not just arresting people because a facial recognition system says maybe it's the same person. But yeah, maybe we decide we want the police to use this. Maybe we decide, okay, we're okay with companies using it to keep out shoplifters. But we don't want them using it for other things like discriminating against people based on where they work, or because they're an investigative journalist or a government official.

[00:55:48] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:55:49] Kashmir Hill: And maybe we don't want us to have it like that you can just identify another person without their consent, you know? Search their face. I do think that these are regulatable and that we could pass laws. We need to choose to. We need to act to protect anonymity if we think it's important. I could also imagine a version of this that people opt-in to, like a company that knows our social graph like a Facebook or a Meta. They're working on augmented reality glasses and their chief technology officer has said, "I'd love to put facial recognition capabilities in this. It would be great if you're at a cocktail party and there's this person that you've met five times before and you should know their name. And you just look at them and our glasses tell you who they are." I could imagine a consent model for face recognition where you say, "Yeah, I'm going to opt-in. I'm going to set the privacy settings for my face the same way I do with my Facebook profile and set it to public or set it to recognizable by friends, people you're connected to or you make your face private. I could kind of imagine that. I feel like that's the American style of embracing facial recognition technology that it's like, "Yeah, I'm okay with this." Like I want to be recognized because of whatever benefits you get from being known.

[00:57:00] Jordan Harbinger: Casinos use this, don't they? To keep out card counters and things like that. I feel like that's the original, my original introduction to this was casinos can actually use this and it was amazing. And that was probably like 10 years ago.

[00:57:11] Kashmir Hill: Absolutely. They're very early adopters. Also using it, there's people who have problems with gambling who will put themselves on lists of like, "I don't want to be led into the casino." And so they'll use facial recognition technology to keep those people out as well. And what kind of scares me is that 10 years ago, the technology didn't work that well.

[00:57:28] Jordan Harbinger: No.

[00:57:28] Kashmir Hill: Especially in the real world. So I do wonder who was flagged, who shouldn't have been or who the technology missed. But yeah, casinos are definitely users. We're starting to see it in airports, airlines like TSA is using face recognition as you're going through. So it's spreading quickly, which is why I think we need to assess it right now before it's just so widely deployed that we have lost our anonymity.

[00:57:52] Jordan Harbinger: Look, TSA is one of the one places where I'm like, "Okay, maybe airports really need this." Because you don't want somebody to flee who's got a warrant out for their arrest. You don't want somebody who is a known affiliate of a terrorist organization, boarding in a commercial airliner. You don't want that kind of — that's like the one use case where I think most of us can agree is probably where we want this technology in use.

[00:58:17] Kashmir Hill: Well, this has been like a point of friction. In the US, we've really resisted the idea of putting facial recognition cameras out there, like putting facial recognition in surveillance cameras for real time surveillance. There's been pushback here. And it was funny because I was talking to a vendor from the UK where they're more open to that use case and he is like, "What's the matter of Americans? Why won't you guys just let us put this everywhere. Be such an easy way to find wanted criminals, missing persons, et cetera, fugitives." And we don't seem to like that. Like right now, the way we're using it is, you knowingly look into a camera, or using it to solve crimes where you have surveillance camera footage that was recorded previously.