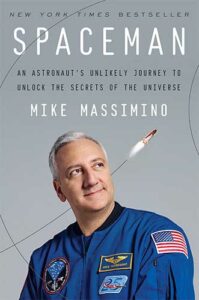

Mike Massimino (@Astro_Mike) is the astronaut who sent the first tweet from space and one of the few spacefarers we’ve had on this show! He’s the author of Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe. [Note: this is a rebroadcast from the vault.]

What We Discuss with Mike Massimino:

- How is bedtime on a space shuttle mission a lot like a slumber party?

- Why assembling a team around you is crucial for success — whether orbiting or staying on the surface of the planet.

- Why it’s important to take small, deliberate steps in the right direction for the sake of your own happiness.

- How to stay focused on the task at hand in the face of disaster by thinking like an astronaut.

- Why even astronauts have imposter syndrome.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

On this episode of The Jordan Harbinger Show, we talk to someone who has made the journey and returned to tell the tale — Mike Massimino, astronaut and author of Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe.

Listen to this episode in its entirety to learn why Mike is glad he took the time to work a few years instead of going to graduate school fresh out of college, how Mike found a niche that made him an appealing astronaut candidate to NASA, how a lifelong mentor gave Mike a nudge in the right direction when he was feeling aimless about his future, why Mike realized that paying for further education and giving up a stable job making good money was a far less costly path than not pursuing his dreams, what legacy Mike hopes to leave for his kids, why Mike considers the concept of “doing it all on your own” is outdated — and why you need a team around you to be successful, why we shouldn’t take the beauty of Earth for granted, what Mike sees as the future of space travel, and lots more. Buckle up, listen, learn, and enjoy the ride! [Note: this is a rebroadcast from the vault.]

From orbit: Launch was awesome!! I am feeling great, working hard, & enjoying the magnificent views, the adventure of a lifetime has begun!

— Mike Massimino (@Astro_Mike) May 12, 2009

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

Thanks, Mike Massimino!

If you enjoyed this session with Mike Massimino, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Mike Massimino at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe by Mike Massimino | Amazon

- Mike Massimino | Website

- Mike Massimino | Instagram

- Mike Massimino | Facebook

- Mike Massimino | Twitter

- Mike’s Appearances | Neil deGrasse Tyson’s StarTalk Radio Show

- Mike’s Appearances | The Big Bang Theory

- The Right Stuff | Prime Video

- STS-109: Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Mission

- STS-125: The Final Visit to the Hubble Space Telescope

Mike Massimino | Unlocking Science Secrets with an Unlikely Spaceman (Episode 516)

Jordan Harbinger: Special thanks to Hyundai for sponsoring this episode.

[00:00:02] Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:05] Mike Massimino: I believe we live in a paradise. I believe we're very, very lucky to be here. We need to take care of it, but I think we're very, very fortunate to live here. I'd only imagine what heaven would look like, but I can't imagine anything being more beautiful than our planet. And I do think we live in a paradise and we should really treasure every moment that we get to be on this planet.

[00:00:27] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We have in-depth conversations with people at the top of their game, astronauts and entrepreneurs, spies and psychologists, even the occasional Emmy nominated comedian, national security advisor, or economic hitman. Each episode turns our guests' wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better critical thinker.

[00:00:54] If you're new to the show or you're looking for a handy way to tell your friends about it, we now have episodes starter packs. These are collections of your favorite episodes, organized by popular topics. That'll help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show. So if you're new or you're trying to get somebody else into the show, just go to jordanharbinger.com/start. And that is a great place to get a sample of what we do instead of just diving into the feed. For some people that might be a little bit overwhelming, but either way, I always appreciate when you share the show with others. So please go ahead and do that and take advantage of those starter packs. Again, jordanharbinger.com/start.

[00:01:28] Today, we're talking with Astronaut Mike Massimino. You should listen to this episode. If you want to learn why assembling a team around you is crucial for success why it's important to take small deliberate steps in the right direction for the sake of your own happiness and your legacy, and how to stay focused on the task at hand, in the face of disaster, by thinking like an astronaut and learn why even astronauts have imposter syndrome. Also, he's got some great stories about almost screwing up multimillion-dollar missions in space/almost dying in space.

[00:01:57] If you're wondering how I managed to book all these great authors, thinkers, and creators every single week, it is because of my network. And I'm teaching you how to build your network for free over at jordanharbinger.com/course. And by the way, most of the guests on our show, they subscribe to the course. They contribute to the course. Come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong. Now, here's Mike Massimino.

[00:02:19] First of all, you've spent a lot of time and space at 571 hours and 47 minutes. And that includes 30 hours and four minutes of space walking. At some point, do you wake up in the morning and go, "Wait a minute, where am I?" And realize, "I'm in space. I'm still in space right now. This is real."

[00:02:38] Mike Massimino: Do you mean when you're in space or after?

[00:02:40] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, of course. I'm sure you wake up at home sometimes and think, "Oh good. I'm not on the Hubble. I can go get a cheeseburger," right? But while you're in space, do you just never forget that you're actually all the way up there because of the whole setup and the weightlessness and you know, having Velcro pillows strapped to your head, et cetera?

[00:02:55] Mike Massimino: No, I mean, it's just like when you wake up in a hotel room where you're not used to — you know, you wake up expecting to see your home, in your regular bedroom and then you wake up and you realize that like that first night, you know, you realize that, "Whoa, where am I?" Kind of this eerie feeling of "where am I." Just like you get, when you're waking up in the stranger room or a hotel room, or sleep in an airplane and wake up after a deep sleep and remember where you are. So it was like that the first couple of times waking up, I guess the first day, first night or so. But then after a while, you know that you are there and you could wake up and look familiar, then you come home when you wake up at home and it looks familiar, like you are ready to float out of bed and that won't work. You get in both directions, I guess.

[00:03:35] Jordan Harbinger: When I wake up in the morning, generally the first thing I noticed is, okay, you know, I probably got a cat on my head or something like that. Or, you know, it's a little warm in the room. When you're in space, it seems like there would be a completely different set of considerations. I mean, you're not just floating around up there, obviously you're strapped at something and whatnot. When you wake up, what's kind of the first thing that you notice when you're in space? So is it weightlessness? Is it the temperature? What is it?

[00:04:00] Mike Massimino: I think when you first wake up, like, "Wow, that was a quick night. I need more rest," you know, just like a regular night. Sort of like, "Oh, it's time to get up already." But then you're like, "Okay, this is going to be a fun day or an interesting day." For me, on the Space Shuttle was more like a slumber party. So you have your crew mates around you in their sleeping bags. You are all kind of in the same room. So you wake up and you see everybody else and you see who's up and who's not and you kind of go through the routine of getting out of your sleeping bag and rolling it up. Routine kind of becomes pretty important, I guess, because you have to get your stuff out of the way. On the shuttle, we have our own little crew cabin. Your little personal crew quarter to sleep in. In the Space Station, they do, they have their little personal area there that they can sleep in. You can close the door, but in the Space Shuttle, it was more like a big slumber party.

[00:04:48] Jordan Harbinger: So how close are you to the next guy or gal right next to you? I mean, do you have any personal space whatsoever?

[00:04:54] Mike Massimino: Oh no, yeah, we have some personal space but they are kind of around the wall or someone's on the ceiling. You're just kind of scattered around the cabin. You're not knocking into each other or necessarily banging into each other, but you're fairly close when you wake up and you see everybody. You see who's in their sleeping bags or who's up or who's in the bathroom and that kind of thing. You just float out and start your day. Usually, you'll take off your sleep mask and put that away by the little kit, bag of stuff that I had, you know, my sleep kit with you clogs, sleep mask and whatever else I needed for the night — I little hat that I would wear if I was cold and socks to keep my feet warm.

[00:05:33] Jordan Harbinger: So you've got your sleep kit. Are you basically, then carabiner kind of into the wall of the shuttle because otherwise, I feel like you could wake up and you just have your head, you know, right in someone else's personal space or you end up floating over to the bathroom or something in the middle of the night or banging your head on something.

[00:05:49] Mike Massimino: Your bed or sleeping bag has various little hooks, not carabiners, but like easy, quick release hooks. And there's different things you can hook it to on the Space Shuttle. There's things that you can hook into. So you kind of hook the sleeping bag to the ceiling or hook the sleeping bag to the wall, and then you float inside of it. As you're inside the sleeping bag, you are floating, but you don't float away. You'll stay attached to the wall, but you're still nonetheless floating, hovering kind of over the wall or the ceiling or wherever it is that you are. So you're not going to float away, bang your head, and wake up your friends. You're going to stay in that one area, but you just float in that one area because your sleeping bag is secured.

[00:06:31] Jordan Harbinger: Got it. I mean, of course, when we were little, we learned about astronaut ice cream and that's pretty much it. And then of course, one kid says, "How do they go to the bathroom?" And that's kind of the end of the space lesson, at least in the '80s. So I'm still not even sure how that works. I mean, I think the one thing that I have in common with astronauts is occasionally during a really long show, I too need to pee into a bottle, but I think you probably have a little bit more of an excuse. So the first time you signed up for the astronaut program, essentially, and I know it's not as simple as that.

[00:06:58] I mean, in the book you go over just repeated defeats and setbacks from your eyesight to your PhD thesis and things like that. I mean, there's no set path to just becoming an astronaut. Contrary to what every little kid, sub-10 years old, thinks when they say they want to be a spaceman or an astronaut, there's no application process. You don't upload your resumes someplace and then go to school for this and then end up repairing the Hubble. It's more of a convoluted process. Tell us though, what was the thought process going into this? I mean, what makes somebody want to be an astronaut and then actually freaking do it?

[00:07:32] Mike Massimino: I mean, there is an application. You don't sign up that said you apply. And there is an application that you can fill out. Now, it's online. I used a typewriter for mine, but say after you've been in school and so on, there's no straight path. That's absolutely right. You follow something that you're interested in and study what you're interested in school, do a career or whatever. It seems to me, things just kind of open up and happen and you take opportunities. But the thing you can do is you can keep applying. And so that's what I did, but I think it's important. I had to learn that. You're not guaranteed that you're going to get in and there's no one set path. And the path that's good for someone else is not going to be good for you. The path that's good for you is not going to work for somebody else.

[00:08:13] There were some jobs that are kind of like, you know, there was sort of like a pattern to it. Some of the test pilots, for example, that was more of a traditional pathway, become a high-performance aircraft pilot in the military. And you go to test pilot school. Then you have that credential at that point that you can be considered to be an astronaut. You know, you've done those things to be a test pilot astronaut or a pilot astronaut. But even that doesn't have a straight path, there's different backgrounds for each one of those pilots too. But particularly when you get into the civilian ranks and some of the other military occupations, other than pilots, it's kind of whatever works for you. There's no set path to doing that.

[00:08:50] But as far as what makes someone want to do it, for me, it was the little boy dream of wanting to walk in space, wanting to walk on the moon, like Neil Armstrong did. When I was six years old, I saw those guys walk on the moon and that got me interested. I thought this was a great thing they were doing and the coolest thing that anybody could do, and these guys were super rock stars, you know, they were the coolest guys on the planet and I want it to be like them. But I quickly realized I wasn't like them when I started getting older, I wasn't going to be one of these military test pilots. I just wasn't for me. And I kind of gave up on the dream. I didn't think it could happen.

[00:09:26] And then when the Shuttle Program came around and when I was senior in college, the movie, The Right Stuff came out and I went and see that. So that was about the original seven astronauts. And that started to rekindle my brain, the wonder of space. And then I sort of think it was cool again. But then I started finding out more about it. The Shuttle Program began in 1981 when they first, the Shuttle, selected the first group of Shuttle astronauts in 1978. And when I was done with college and got interested again, because of this movie that I went and saw, I started reading about the astronauts and who they were. And I found out that they weren't all military test pilots. They were women and people of color and different ethnic backgrounds and civilians. It wasn't just military test pilots who were doing this any longer. And they were so big part of it, of course, but military test pilots, but it was all types of people who were becoming astronauts, not too much different than who I was I thought, and I never really thought I could actually do it really, but I thought I had to at least try.

[00:10:24] And it wasn't that crazy of an I needed to get some experience to make myself even eligible to be considered. And even if I got the eligibility where I was qualified to be an astronaut, I met the minimum education and experience qualifications. There are thousands and thousands of people who want to do this and just a handful that get selected, but I thought maybe it could work out. And then if not, maybe by trying to do that, it would lead me to something else in the Space Program and give me the ambition of trying to get more education and to do something that I really was passionate about, which was the Space Program. And I realized that that's really what I was interested in all along. I just thought I could never do it and I thought maybe I can't become an astronaut, but maybe I could do something in the Space Program for a career.

[00:11:08] I started taking steps toward that. And the big step I took after working for a couple of years for IBM after college, I left my job and went back to school and went to graduate school at MIT and when I got my master's degree, that's when I started getting the credentials to be eligible, to meet the minimum qualifications and that's when I started applying.

[00:11:25] Jordan Harbinger: Now, at what point where you working at IBM because that was the safe choice? I mean, it's earlier in the book and finally someone that you worked with sits you down and says, "What are you doing here, man? You got to get out of here, like save yourself." What would you say to someone working a job right now that they think is just suffocating and they may have the same choice? I mean, do you recommend that people always go for it or do you think there's a place for playing it safe?

[00:11:49] Mike Massimino: Yeah, you got to go for it. I think you have to be honest with yourself about what you're really interested in. For me, it turned out that, that wasn't the worst thing for me to do — was take a couple of years after college in work. Because if I were to went to grad school right away, I wasn't really into the space thing right out of college. I think that was part of the issue. I think getting a college education is a great thing. And I had a good college education under my belt at that point but grad school I felt anyway was a little bit more specialized in that. You have your basic education that you get as an undergrad, but after going to go to grad school, I thought I needed a better idea of what it is I really wanted to do. And so what I did is I decided to put grad school on hold and work and think about it. So that was a useful time, but it became evident that a couple of years of that was enough and it was time for me to get going.

[00:12:36] And I see this in a lot of people with my close friends and family members too that go through this, that they're unhappy with what they're doing. And sometimes you're unhappy in your job for different reasons. Sometimes you just feel like you don't like people you work with and you're just not a right fit for it. Or you're not doing something that is meaningful to you, or you're not passionate about it. You know, in my case, I felt I a great job had good people to work with and I could see myself doing it, but I just wanted more. I wanted to feel like what I was doing was really important to me. Not that it had to be important to everybody. But I didn't think what I was doing. There was something that I was passionate about. And I thought it was a good job in a good way to earn a living, and you're part of a great team when I was working before I went to grad school. It wasn't my passion and I want it to be part of the Space Program.

[00:13:19] And in order to be part of this Space Program, I had to make a change. I was going to have to leave New York and go somewhere else to school and that would be the best thing for me. And that's why I went to MIT and I was able to get in there. But if I didn't get in there, I would have went somewhere else. But I think that it's important to be honest with yourself,

[00:13:34] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, you don't have to jump off a cliff, if you're not doing what you want, but you do have to take steps in that direction.

[00:13:40] Mike Massimino: I think it's important to start taking steps and it'll open up opportunities for you. What I liked when I was an undergrad and what I started to read about and find interesting was this idea of human factors of people controlling machines and how to design the interface, whether it's a cockpit or a car console or computer program or whatever such that people can interact with it effectively. And what I got really interested in was the robotics of human controlled manipulators and robots working in space. And when do you use the robot? When do you use the person? And what's the right combination of that? And I found that to be really interesting.

[00:14:16] And there was a professor that became my advisor, Tom Sheridan at MIT, who had done a lot of research in this area for controlling robots in space and in nuclear environments when they started handling nuclear material on the 1950s and 1960s, and also under sea, submersibles, that would find the Titanic and so on. He worked with that. How do you control those vehicles? How do people control those things and operate them? And I found that to be really, really interesting. And that's what I was able to find a niche in something that I could study in graduate school that I found interesting that also had applicability to NASA and Space Program.

[00:14:54] And you mentioned about, you know, having people who cared about me. There were always these mentors, whether it was a teacher or family friend or neighbor or whatever, coming in at the right time to help me out and give me a nudge. I was a guy named Jim McDonald, who I worked with after I was a junior in college. I worked with him at an engineering company on Long Island called Sperry. And this was my first big real engineering job where I had to wear a tie to work and so on. You know, I think he saw something in me that I just wasn't happy with doing what I was doing. And maybe, the traditional engineering job at a big company might be okay for me, but I needed to be in the right area. And I wasn't really interested, necessarily in just being an engineer. I wanted to do something that I thought had more meaning to it.

[00:15:33] And for me, what I was most interested in was I ended up being in the Space Program. I kept in touch with him. I see Jim McDonald. He has been a mentor my whole life for me and for a good friend. He was a guy to try to shake me out of it when I was working after college saying that, "You know you might want to think about what you're doing. You need to move on with what you really love and take those steps before it gets too late."

[00:15:53] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I mean, you mentioned in the book as well. "You only have one life, you have to spend it doing something that matters." And I think it sounds like that spurred you on quite a bit when you were sitting doing engineering internships, things that weren't really floating your boat. It seems like you wanted to live by that and thought, look, life's too short to waste sitting in front of this PC designing user interfaces. As useful as that might be, you want it to be on the front lines.

[00:16:17] Mike Massimino: That time I wasn't even during user interfaces. I was working as a systems engineer putting systems together, which was fine, but it's more of me, I want to be involved with the Space Program. And I think the point is that you, the most important thing you can do with your life is what you do with your life and how you're going to spend that time. And you pay for that. It's not money. Like when I was looking at going to grad school, there was this cost associated with it. You know, it was going to be a cost that I would have to stop working, where I had a real job where I was making pretty good money right out of college. So now, going back to school, I was going to give that up.

[00:16:50] In addition to that, I was going to have to figure out a way to pay for school. And eventually, I was lucky I got NASA fellowships to help me pay for it. I was hardly making anything. I was making a little bit of money which is covering my tuition and I had a small stipend, so really was not making money in my 20s. And that was where I spent my time in my 20s was predominantly spent in school where you're paying for the privilege as opposed to getting paid to do something. And I remember thinking about that, that I was going to be these years where my other friends were out there making money and, you know, doing that. But so it a money cost with going back to school. But I think the cost for me of not doing that was higher because I was going to pay for it with my life and that I would not be able to pursue what I wanted to pursue in life, unless I made that change.

[00:17:35] And I wasn't sure that this was exactly the right way to go. There were other ways to try, but I thought at least going and getting at least a master's degree at a place like MIT was a good idea. And that was something I felt like I really should do and wanted to do. And if I didn't do it, I'd always regret it. I think that's the way you need to look at things, not in dollars and cents, but in how you're going to spend your time on the planet. You know, how do I want to spend these next couple of years? Do I just want to — we worry about making money or do I want to do something that I think is really important to me. And the opportunity to go and get a graduate education at MIT was extraordinary. To be there on those types of people, learning the things I learned, being totally involved in learning about technology and engineering, and what was going on in Space Program and being surrounded by people who felt the same way was just an extraordinary experience.

[00:18:25] Jordan Harbinger: And were you thinking about legacy at this time. In the book you say, "I don't want to tell my children how to live life. I want to show them." Were you thinking of legacy or were you just thinking, "All right, I need to do something important for myself"? Or did you have a wider perspective on this? Do you have a longer timeline in mind?

[00:18:41] Mike Massimino: Well, I think it's both. I think I wanted to be a happy person and happy parents, eventually. Everyone wants their kids to be happy and to pursue their dreams and so on. And I think the best way to do that, to have them do that is to show them how to do it. And to have an extraordinary life if that's what you want is not impossible. It might be difficult to attain. I think that happiness in that part of your life and your professional life is attained by at least trying. And at least like you feel like you're doing something.

[00:19:06] There was a period of years when I was in graduate school and beyond that, I was trying to become an astronaut. I guess it was 12 years, by the time I thought that I wanted to try to pursue this. And after get out of college in 1984, until the time I was picked in 1996. And those 12 years were pretty much filled with this journey of trying to get to NASA as an astronaut. That's a long time, 12 years, to be following pursuing something. And it wasn't just the idea that if I don't make it, it's not worth it. I don't think that was it. I think it's more like, at least I'm trying. And it might not work out, but I want to try and I don't want to give up. And that's what I thought the important thing was. And if you're doing that — as long as I was doing that, giving it my best shot or at least trying to give it my best shot that I felt satisfied.

[00:19:49] And it may not work out for other reasons. You never know why. If you will or won't and it might not, but I certainly was going to give it my best shot. And those years were interesting because even though I wasn't an astronaut, I didn't think truthfully that I would ever make it. At least I knew I was putting my best foot forward and trying. Now, that's what we would want for our kids, but it's also important for us. I mean, I was doing it for me because I really wanted to do it. And the thought of not trying was unthinkable, but at the same point, I wanted to set a good example in that regard, at least trying to pursue something that's important to you and there is no reason to settle.

[00:20:24] Jordan Harbinger: You hinted on this earlier as well. And I saw this in the book. You said, "I've never achieved anything on my own. People have always pushed me to be the best version of myself." And I thought this was really interesting and important because, of course, you get everywhere with the team, but there's also this myth, especially in the United States or the west, I should say, in general of this kind of self-made man, the guy who's just pulling it all together on his own kind of John Wayne figure. And it seems like that was not the case for you. You had a team together to help with your PhD. I mean, there's, you're recollecting how your buddies are tearing apart, your thesis almost for sport. At this point in college, there's no benefit for them. They're just kind of enjoying watching you squirm here. And you realize that if you work hard and get help from good friends, you can do pretty much anything. It sounds like you had the opposite of a bootstrap, do-it-all-myself attitude.

[00:21:14] Mike Massimino: Yeah. I think that people learned it are successful in different ways and they weren't torturing me just to see me squirm. They were helping me. I asked them to help me prepare for my doctoral exams and I did it for other people too. You grill each other and quiz each other because it's better to do that amongst friends and prepare for when the professors get at you. So they were helping me and they really did a good job in getting me ready. And I think that for me, what I found was that I was more of a team guy, more of a team player where I enjoyed trying to bring out the best in other people and having them try to bring out the best in me. And the concept of team, even in a situation where you try to get a PhD, which is seen as an individual accomplishment, I didn't necessarily see it that way. I felt like there's a lot of support that I needed from my friends, from my lab mates, and from my professors and from my advisor and so on, to help me. And they were there to help me and I try to be there to help other people.

[00:22:06] But I think that the sense of doing it all on your own, I think that's outdated. I don't know when that ever existed, but you're going to need help. You need a team around you to be really successful. You know life is a team game. You're not going to be successful on your own. And so I think when you have success, you need to think about it, "All right. Yes, I worked hard. I deserve what happened. Maybe I deserve that," but there's usually plenty of credit to go around and you need to be grateful for the help you got.

[00:22:34] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Mike Massimino. We'll be right back.

[00:22:39] This episode is sponsored in part by BiOptimizers. Jen's been struggling with leg cramps, but she noticed a big difference when she started taking magnesium. Magnesium Breakthrough by BiOptimizers is an organic full-spectrum magnesium supplement that includes seven unique forms of magnesium. I didn't know there was more than one, but whatever. BiOptimizers have five-star reviews saying, "I'd give it a hundred stars if I could. Within one month of use, I went from daily struggles with restless legs, constipation, and poor sleep to no struggles with any of that." So it sounds dramatic. It sounds like magnesium makes you poop, but I'll tell you those leg cramps, they go right away. Please do not run to the store and just buy the first magnesium supplement you find. Most magnesium supplements use the two cheapo synthetic forms. They're not full spectrum. They won't fix magnesium deficiency or help you sleep better probably. There are seven unique forms of magnesium. Magnesium Breakthrough has all of them. Just take two capsules before you go to bed and see how much more rested you feel when you wake up.

[00:23:34] Jen Harbinger: For an exclusive offer for our listeners, go to magbreakthrough.com/jordan and use Jordan10 during checkout to save 10 percent.

[00:23:41] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Better Help online therapy. Many people think therapy is for crazy people or weak people. Don't you find it interesting that people don't think twice to seek medical help for health-related problems, but think that seeking help for emotional issues is some sort of weird sign of weakness. I don't understand that. Let's be honest, how much easier is it to just grab the closest pint of ice cream, drink your sorrows away. Pretend like our problems don't even exist. It takes a heck of a lot of strength to face problems and ask for help, but Better Help online counseling makes it so easy, freaking easy. You fill out a questionnaire. You get matched with your counselor under 48 hours, video sessions, phone sessions, unlimited messages with your therapist, all from the comfort of your own home. You don't have to drive. You don't have to park. You don't have to read Dwell magazine in the waiting room. Everything you share is confidential. If for any reason you're unhappy with your counselor, you can request a new one at any time, no additional charge.

[00:24:33] Jen Harbinger: Our listeners get 10 percent off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan. Visit better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan and join over 1 million people who've taken charge of their mental health with the help of an experienced Better Help professional.

[00:24:46]Jordan Harbinger: This episode is sponsored in part by Hyundai. Hyundai questioned everything to create the best Tucson ever. Every inch of the all-new Tucson has been completely re-imagined resulting in an SUV loaded with available innovations, both inside and out. From design to technology to safety, every aspect of the new Tucson has been improved upon. Hyundai's digital key allows you to transform your smartphone into a spare key, which is so convenient because if you're like me, you can never find your keys, your wallet. It's one less thing to remember. LED daytime running lights, they're stylishly hidden within the cascading front grill, making them invisible when not in use. Set multiple user profiles in case you share your car with other people. I love that I can hop in and have the seat mirrors, climate control, radio presets, all personalized just for me. Plus a 10.25-inch full touch infotainment screen, but they blind spot view monitor, which is a great safety feature especially when merging. The SUV has been completely redesigned inside and out to create the best Tucson ever. Learn more@hyundai.com. I feel like I should say that in a breathy voice. Learn more@hyundai.com.

[00:25:45] And now back to Mike Massimino on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:25:50] So you're at MIT, the Smart-Kid Olympics, the best of the best. You mentioned in the book, "And then there was me, a regular guy from Long Island." It sounds like what we call imposter syndrome, which is essentially, "I'm the guy that slipped through the cracks. What am I doing here?" Is that something that you still feel that way sometimes? I mean, did you even have that up there? You're with this amazing all-star team. Did you still have second thoughts, like maybe I'm the ringer here?

[00:26:14]Mike Massimino: Yeah. When I was at MIT, I felt like — I'm looking over my head here with, look at all these smart guys, but I think a lot of them, a lot of the men and women up there felt the same way. You know, like what's going on here? I think I probably felt it more than most though. I think it just did. I just get the sense that I did. In the astronaut program too. I mean, I felt like — you know, it was strange. I mean, at times I felt like, "These guys are so tremendous, these men and women are so tremendous. What am I doing amongst them here?" But at the same point, I felt like I did have something to contribute and there were things that I could do well, and I just wanted to do well. I wanted to be a part of the team. I want to do the best I can. I just worked really hard, but I always felt like, particularly, I think at MIT with the level of brain power they have up there, I wasn't your typical MIT student. And I felt like whatever that means, I felt like I really had to work hard to keep up.

[00:27:04] Jordan Harbinger: What was your first thought when you saw the fueled rocket? I mean, you'd been to the rocket before you got in, of course. What were your thoughts when you saw this thing fueled up, ready to go and you're walking in? I mean, there's got to be some heavy-duty emotional stuff going on when you're about to actually get in and take off and leave earth.

[00:27:21] Mike Massimino: Yes. When I write about it in the book, there is that you get out to the launchpad and the rocket is fueled — I hadn't been around the fueled Space Shuttle before, and is a burn off of the cryogenic fuel smoking. It looks like smoke though it's vapor going into the air and it's making these ungodly noises and it looked like it was alive. It looked like a beast, like an actual beast alive. And the thought that went through my mind was, "Maybe this wasn't such a good idea," but it was too late by that point, it was time to get off. Get on a spaceship and let's take our risks, roll the dice on this one, but it really is very intimidating.

[00:27:55] And to get the space to go from zero to 17,500 miles an hour in eight and a half minutes to get to orbit requires an extreme amount of power and a huge, powerful machine, the biggest, most powerful machines ever built. These beasts that take us away from the earth. The power that is harnessed in there is really something that — you know, we try to control it, but it is right on the edge of uncontrollability, just in its other power. It's amazing that people can build machines that can do that. It just really is incredible that we can do anything that powerful, but we do.

[00:28:31] Jordan Harbinger: Do you think about the safety factor or death when you're going out there or are you just too focused on the game, too excited, this is the moment?

[00:28:38] Mike Massimino: I think I thought about what might happen. I mean, safety, you do the best you can. We're trained to operate safely, make sure you check everything and make sure you check the other guy and the other guy checks you. And you're very open to making sure that you don't make a fatal error and that everything is just the way it's supposed to be. And you have all the people on the ground and you are trained on how to operate in such a way that would be safe so that if you do make a mistake or something is not quite right, that you or someone else will be able to catch it, because you'll help them see what's going on and come to the conclusion that there is something wrong. That could be a safety problem. So you want to be very vigilant about what's going on and help those around you be vigilant with you. And so we're trained to do that. And so the safety part of it, I knew we would try to do the best we could. We are as safe as possible, but you also know that there's that uncontrollable factor with this because you're doing something that is so dangerous, that even if you operate safely and everyone does their job, that's just the nature of what you're doing can overcome that. And it could be a bad day.

[00:29:45] So I certainly thought about what the consequences were and what could happen and tried to be ready for it, I guess, if that was going to happen. But I thought about it more ahead of time. And particularly in the weeks, right prior before that, I thought more about it, about what might happen. Not worried about it, but just trying to appreciate the life I had and that if something did happen, that whatever I left behind was in as best shape as it could be. And then once you get out there, especially on the launchpad, it's different thinking about something is usually a lot worse than doing it. And I found if there was something I was scared about, or even up to this day, something I'm nervous about or something that worries me thinking about it as always much, much worse than actually doing it. For actually doing it, you're taking action. Action is always better than inaction. And if you worry about something that's going to happen in the future, like a space launch, when you can try to prepare and study and do all that, but just the basic nervousness, worry about it if something bad happens, there's really nothing you can do about that. But then when you get into it, And you're going through the checklist. It's not as scary at that point, but thinking about it was always worse.

[00:30:49] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I can see that I've watched the clip from the Big Bang Theory where you're going up in space. I don't know if it's a Soyuz or something. There's a Russian guy and there's Howard Wolowitz and it's like, "This is the moment. We're doing it." And Wolowitz goes, "I actually have very mixed feelings."

[00:31:04] Mike Massimino: Yeah. I think I said, "I love this but that's ignition. I love this part." The other guy goes, "Me too," the Russian guy was, "Me too." And then Wolowitz says, "I have rather fairly mixed feelings." That's all the writers in the show. That's just saying a line, but the writers come up with the lines for us.

[00:31:18] Jordan Harbinger: Of course, it is brilliant at some level, because I was thinking, I don't know if I would say I love this part because you know, at some point I don't know what all those feel like, or the fact that there's just massive amounts of explosions and fireballs underneath. And we're about to hurdle off into space. I think I would just be extremely nervous. Then again, you've trained for this. You're excited. There's probably so much adrenaline going that I don't know what you're feeling at that point. I don't know if he can feel anything. It seems like they kind of thing that would just make you go numb. Are you a natural thrill secret though? Is that something that you've always had in your blood?

[00:31:49] Mike Massimino: No, I'm not, I'm not. So I wouldn't say something like that. I was acting when I said, "I love this part," that was acting here in the Big Bang Theory television show that I did where we launched. But no, I'm not a thrill seeker. Some of my friends were, I mean, especially my test pilot friends, they liked doing some extreme stuff, but no, I never was an extreme sports thrill seeker, kind of like jumping out of an airplane. Let's go, hand gliding. Let's go jump off the mountain and see what kind of guy. I was a little more conservative and not used to doing that sort of stuff. I think I was out of my comfort zone a lot as an astronaut, but there was a sense and what we were doing in our training to build up the experience and the confidence we needed in case something did go wrong on the day that we could react appropriately. So yeah, for me, it wasn't, that wasn't really fun. It was a great experience. I'm talking about the real shuttle flight, not the space flight in the Big Bang Theory. But the real one, you know, for me, it was fairly exciting, both fun and also in a kind of a nervousness sort of way, as well as a lot of intensity. And it's fairly stressful as well. You know, that was something I had to learn how to deal with.

[00:32:53] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I mean, you've said in the book, no matter how bad things are, you can always make them worse. When I first heard it, I thought, what kind of attitude is that? And then I realized, actually, that's perfect because you realize that you can only focus on the things that you can control. What does that phrase mean for you in terms of training, in terms of your life? Because it's a little counterintuitive, like, "Oh my gosh, thanks for the vote of confidence, Massimino. I can always make it even worse than it is now. Thanks for the reminder."

[00:33:16] Mike Massimino: Yeah. I wouldn't think it's important and I don't think it's necessarily a bad thing to remember. I think it's a good thing to remember that we tend to think, make things worse than they really are. When something happens, whatever it might be, you break something, you try to fix something and you break it, you know? Or you're like, "Oh, well, that's a pain. And now I've got to do something extra." What's the tendency that I find is that you make one mistake and then you're like, oh geez, I'm going to have to spend 10 minutes to fix that. I don't want to spend those 10 minutes. So let me rush through this and make that time up. And then by rushing you break something else, which now you're not just going to be 10 minutes, but it's now it's another 15 on top of that, whatever might happen, and you just make it worse and worse. And so generally the first mistake, however, bad it might be isn't game over. It might be, "All right. It's very rare that one mistake ends the game. That was bad, but let me contain it. Let me not make it worse. We had this happen, but things can get worse."

[00:34:13] So for example, what I found when I was training and what I found in space was is that if you make a mistake — so you break something which I did actually, you make a mistake and all of a sudden you've created this problem as bad as it might seem, it could get worse. And right now, you know, at some point, if you're working on something that's broken, maybe only part of what you're working on is broken, not the entire piece of equipment. And you could lose your tools. This is what I was thinking of during spacewalks that, yeah, I made a mistake, but I could really make this worse. If I made a mistake and all of a sudden I unhooked myself and I started floating off into space and they got to come get me. Now, I've made it a lot worse because I was nervous and not thinking because I made a mistake. Or if I made more mistakes and I lost tools, for example, losing a tool, that's going to help me fix this problem. Now, I've made it worse. All right. So I've made this mistake. I don't want to make it any worse. Let me try to contain it in where it is right now. It's not great, but it could always get worse. And I think that's what we forget. When we rush and we try to make up for the mistake we made and we don't keep a cool head and we make it worse. And then we've got even a bigger problem to deal with.

[00:35:20] Jordan Harbinger: You're referring to repairing the Hubble telescope, I think, which as you stated is essentially brain surgery in space. And you end up with a stripped screw, which a stripped screw in space. At first I thought, oh, you stripped a screw. I hope this isn't going to be the whole story. And then I realized, well, you stripped a screw in space. You can't really dig your fingernail under there or grab a screwdriver from a toolbox and hammer the thing off. This is a, I don't know, $76 million or something, some telescope with a piece on it that you can't get another one, unless you go down to North America and grab one, which is not an option. Tell us about that harness that almost foiled the entire mission, because that was kind of a brilliant little example of something that if it happened anywhere else in the world. So what, and the fact that it happens in space could have killed you and destroyed the mission, then possibly the whole Hubble telescope. The harness floats off and you had to jump up and get it, but that's fine if you're an Albuquerque, you got to jump up and grab something. It's not fine, when you jumping could actually catapult you into the abyss of nothingness.

[00:36:24] Mike Massimino: It was interesting. What happened was — that was on my first spacewalk of my second mission. For me, it was a cable or harness, we call it, it was a cable that needed to be hooked up, to deliver power to this instrument that had a power supply that had failed. But we had to work around where we were going to hook this power harness to it and put it to another supply and so on. And this cable, I was going to have good access to it even was going to be the big repair was going to happen the day after, by the other team. We have a team of spacewalkers. But the spacewalk that Bueno and I would do and that they gave us good access to hook up this cable for these guys better than they were going to have tomorrow when we rotated the telescope in a different direction.

[00:37:00] My job was to help them out, do a get ahead for them for the next day and hook this thing up. And it was a cable that I almost always put two hooks on everything that I use just in case one hook came undone the item wouldn't float away on me. But this one was different because I only had one hook available. I was going to put it on that and then go straight into the telescope and install it. But what happened is I was getting this harness, we were having trouble with the gyroscopes that we're installing, and I was told to go to the back of the Space Shuttle and grab a gyroscope, the backup gyroscope that we weren't planning to use. And therefore, it was kind of tucked away in the back and brought it around to the front of the telescope where we were working. So I had this cable on me just with this one hook, that was kind of flopping off the side of me, as I went all the way to the back to get this gyroscope. And then it came all the way to the front, handed it off and somewhere I must've done something to bump that one hook. And I put my waist tether into the handrail on the telescope. And then as I'm just kind of getting myself set, I see this harness, this cable float past my head and up away from me very slowly. And it was about to launch itself away from us.

[00:38:08] And it's interesting when I went through my mind very quickly at that moment was we only have one of those. I knew we only had one. So I knew if we lost it, my friends would not be able to repair the instrument the next day, what they did wasn't going to work without this cable. So I knew that's the only one we have. The next thing I knew was that there was star tracker covers which are very, very delicate. They're right above my head and this thing was floating right past those. So if I left for it, if I left for this thing, I could hit those stars trackers. But I also knew from my habits that I had a waist tether around the handrail at the front of the telescope. And the waist tether meant that I had a leash. And that if I went and grabbed this thing, if I let go to grab it, that my leash would prevent me from hitting those star trackers and will prevent me from launching myself into space.

[00:38:52] So I knew I would probably be okay. And then, so I felt, you know, the split second, I made this decision. So I was going to take that chance and try to grab this thing because I thought it would be okay. And sure enough, that was the case. I kind of pushed myself up a little bit. I grabbed this thing and then I had to tug from my waist to pull me back down to where I was and it worked out fine. If I did not know all those things, I could have created a much worse of a problem by launching myself into space or smashing into the star trackers of when I go in and try to get this cable. But it worked out and no one really noticed.

[00:39:24] Jordan Harbinger: If there's relief that you didn't kill yourself, but there's probably also got to be some relief like, "I think I got away with that and nobody has to know unless I choose to tell them about this," right?

[00:39:33] Mike Massimino: Well, what's funny is that when we're working on the Hubble, we're right in the payload bay and the guys inside — you take turns when you go out and spacewalk, the two teams, but the team inside is looking outside, reading you the checklist, and looking over your shoulder and they see everything that's going on. So John Grunsfeld, my buddy who's inside, and I think he said, "Mass—" you know, before he could really get the words out, I heard him start, "Watch your head," it was over, it was over that quick and no one said anything, you know, and I have a helmet camera on, and I know that everyone in the ground is watching it, but no one said we just kept going.

[00:40:03] After we got back and we were home for about a week or so, we had a debrief, a spacewalking debrief. And we went through that and no one said anything to me, you know about it at all. No one said, I almost forgot about it. And then Tomas Gonzalez-Torres, who was our lead flight controller for the space walking, EVA flight controller, the guy that had helped train us along with this young lady, Christy Hansen, the two of them worked as a team. Tomas was the senior guy and he was going to debrief and ask all the questions. And he was looking at, he was in the front room of the control center during the spacewalks and very intimately involved. I got to know him very well, and became good friend with him.

[00:40:38] He pulls me aside after that. We're walking out of the debrief, actually outside the building. And he comes over and goes, "Mass, I got to ask you something." And the name of his harness was the PIE harness. P-I-E was the acronym. I think it's a power interface extension harness. We call it the PIE and he comes up to me and very quietly goes, "What happened with the PIE?" "What do you mean?" He goes, "I just saw that thing float by your head. You went up and grabbed — what the hell happened? What was that?" He didn't want to ask to embarrass me or whatever. He noticed it, but we just kept going. So he did notice, but I think he's one of the few people that noticed what happened. And it could have been a real problem. If that thing would have floated away, it would have been a real problem, but I just snatched it, before anyone could really notice except for Tomas.

[00:41:17] Jordan Harbinger: It's funny because when we think about space, you know, we all watch all these movies and we think, okay, if you accidentally launch yourself away, you're probably tied to a bunch of different things. Or if we've really watched a lot of sci-fi, we just figure, oh, there's a way they can maneuver and then grab them. But not really right. I mean, if you float in the direction, you're not supposed to float, that's it?

[00:41:35] Mike Massimino: Well, you always have a safety tether on. So safety tether is 85 feet. So if you get that far away, 85 feet long way to be. And we've had some astronauts, we'll get to see a blooper reel. Like don't let this happen to you. With some astronauts have launched themselves, doing a tool chase and they never get the tool. Once the thing gets away from me, it's gone. You're not going to be able to control yourself that accurately to get it. All you're going to do is launch yourself somewhere and create another problem. And then try to reel yourself back in like a fish. We have it a few times, not all the time, very rarely, but still enough times that there's a blooper reel that you can see these things where these astronauts I've made these mistakes. What I think the really the bigger danger for me there is if I would have damaged the telescope because I was in a very delicate area, the telescope, and by launching myself, I could have hit it. But I tell you when I saw that power harness floating away from me, I showed him more than just the harness. I show the future of astronomy floating away and I wasn't going to let that happen. You know, it was a little bit risky, but I figured it was worth the risk.

[00:42:32] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. At some point you're thinking, "I'm going to look pretty bad if we go back and the debrief is — so what happened was we were really close, everybody got up there fine. And then Mass, let the PIE harness go. Don't know what he was thinking. And then we couldn't repair it."

[00:42:45] Mike Massimino: That's right. Right, I'd be to blame. My name would be on all the astronomy books for the reason why we don't know the age of the universe.

[00:42:51] Jordan Harbinger: Right, exactly. Due to Mike Massimino, gross negligence. We have no idea what this galaxy looks like. Is that blooper reel available anywhere in the public domain because that sounds—

[00:43:01] Mike Massimino: No, that is certainly classified.

[00:43:02] Jordan Harbinger: Ah bummer. I was so hoping—

[00:43:04] Mike Massimino: Yeah. I don't know where you'd get a copy of that.

[00:43:07] Jordan Harbinger: Probably not on VHS.

[00:43:09] Mike Massimino: You'd have to dig through the archives and it's probably not worth the effort. It's more of a training tool than it is. It's not like a blooper reel on America's Favorite Videos. You probably find it very boring actually, but for astronauts, it's pretty cool.

[00:43:20] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Mike Massimino. We'll be right back.

[00:43:24] This episode is sponsored in part by Chili technology. I used to struggle to sleep at night because I tend to run warm. I think a lot of us do. On top of that, it's freaking hot these days. I truss around and toss and turn. There's a baby next to me. There's a wife next to me. I can't get cool enough to sleep. The chiliPAD has made a huge difference for me. The bed feels cool. Like you just got in and stayed cool all night long. One of the most important parts of staying healthy, obviously, is the quality of your sleep. It's probably one of the top, top things that has made a difference in my life. An optimized night's sleep, I'm more rested when I get up, I feel like I don't get sick. I'm happier. Or I should say, I need less coffee in order to function. It even helps with weight loss efforts, but even with these significant benefits, most Americans don't sleep that well. We just don't. At least we think we don't and that's where ChiliSleep comes in. ChiliSleep makes customizable climate controlled sleep solutions, the chiliPAD, the OOLER. That's what I've got. They fit on top of your existing mattress. They can warm or cool the bed and each side operates independently. So wife's side is warm, my side is cool. It's a game changer.

[00:44:24] Jen Harbinger: Head over to chilitechnology.com/jordan for ChiliSleep's best deal, which they're offering to our listeners for a limited time. That's chili, C-H-I-L-I-technology.com/jordan for your special offer.

[00:44:36] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by LifeLock. A family was recently surprised to receive a change of address notification that they never requested. This was an attempt to steal their mail and gain access to a lot of personal information that cybercriminals can use to steal their identities. It's important to understand how cybercrime and identity theft are affecting our lives. Every day, we put our information at risk on the Internet. In an instant, a cybercriminal can harm what's yours, your finances, your credit, your reputation. That's one of the reasons that I use LifeLock. LifeLock helps detect a wide range of identity threats, like your social security number for sale on the dark web. If they detect your information has been potentially compromised, they'll send you an alert. I get these alerts. They're kind of scary. I can fix stuff. I can head stuff off at the past. They also give you a dedicated restoration specialist if you do become a victim. So you're not spending a bunch of your valuable time fixing identity theft.

[00:45:26] Jen Harbinger: No one can prevent all identity theft or monitor all transactions at all businesses, but you can keep what's yours with LifeLock by Norton. Join now and save up to 25 percent off your first year at lifelock.com/jordan. That's lifelock.com/jordan for 25 percent off.

[00:45:42] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored in part by Klaviyo. Ever wonder how e-commerce brands that you admire do it, how they know just the right messages to send the right people at the right time. Guess what? Not experience. They have the right data and the right tools./ They have. Klaviyo Klaviyo's data-driven marketing automation platform is sophisticated enough to power those legendary campaigns from the brands that you admire. But they made it simple, easy, and fast enough for anyone to use. Klaviyo helps brands create personalized multi-channel marketing campaigns, using your most powerful asset, your customer data. Klaviyo integrates with all leading e-commerce platforms, helping you use your customer data in real time to send more relevant email and SMS automations. Plus building a marketing campaign is drag and drop easy. You can get started with your first campaign in under an hour and easily build from there with Klaviyo's best performing templates. Klaviyo gives you all the power of an enterprise marketing automation platform and none of the complexity. So you can compete with the big guys. No wonder more than 65,000 brands can't get enough.

[00:46:39] Jen Harbinger: To get started with a free trial of Klaviyo visit klaviyo.com/jordan. That's K-L-A-V-I-Y-O.com/jordan.

[00:46:47] Jordan Harbinger: Hey, thanks so much for listening to this show. Your support of our advertisers keeps us going, but honestly, I just love hearing from you. I love creating this for you. All those discounts, all those codes, you need to support the sponsors, they're all in one place. So if you're bench pressing or jogging or whatever, you don't have to take notes on that. Just go to jordanharbinger.com/deals. And that's where you'll find all the codes, all those special URLs, and promo codes. Please consider supporting those who support this show.

[00:47:13] Don't forget, we've got worksheets for many episodes. This one is no exception. If you want some of the drills and exercises talked about during the show, those are all in one easy place. And that link is also in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast. And now for the rest of my conversation with Mike Massimino.

[00:47:30] Producer Jason was asking if there's a simulator at NASA to try and replicate the launch, or if every time you launch it's the first time you felt that stuff because you simulate pretty much everything, but it seems like the launch would have to be broken down into parts. Like maybe you can simulate the gravity, but not all the controls. Is there something that's just like the inside of that shuttle and tries to simulate the feeling that you're going to get?

[00:47:52] Mike Massimino: There is, but you're right. I mean, you do do it in pieces, but there's no way to get the power of the launch if you just can't do it. So what we do is we have an emotion-based simulator where we practice launches. You tilt back and you move and have hydraulics moving around and shaking you. But if they cannot replicate that violence on the ground, it's just impossible. And then for the G-forces we do a simulator ride, we do a centrifuge ride. There's a centrifuge at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio that we ride that centrifuge. And we go up, we get the G profile for eight and a half minutes. Really what it is with the major part of that is the last two and a half minutes of the launch from six to eight and a half minutes, that two and a half minutes, you get about three Gs on your body. You know, they spin you out and give you the idea of the GS building up. And then you get to those sustained 3G so you can feel what they're like on your body. We get more of Gs not the most I've ever taken. Airplane T-38 that we fly, we get up to six or seven Gs, but those are only for like a split second, a second or two, a couple of seconds. You might get that amount of G-Force. Here for two and a half minutes, it's kind of long for that amount, even though 3G is not that much. It's three times your body weight pushing down on you. So it's like you're on your back. And you've got a pile of bricks on your chest is what the feeling is.

[00:49:04] Jordan Harbinger: With all the other things to worry about and think about at that time, you've got two of you sitting on you like a schoolyard bully basically at that point, right?

[00:49:12] Mike Massimino: Well, that's not so bad actually. All right, okay, you know, just wait until this is over. So yeah, there's really not much for you to do except to kind of take it.

[00:49:20] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Well, I guess you're thinking, "All right, this is a little uncomfortable guess I'll wait until I'm weightless witnessing the miracles of it."

[00:49:26] Mike Massimino: Right. It's not the worst thing, but you know, you're like, okay — you're happy when it's over.

[00:49:30] Jordan Harbinger: Sure. You're up there repairing the telescope or doing any kind of spacewalk, which by the way, you've got over 30 hours of spacewalking. So think about just being out in the vastness of space, looking at the earth, hanging out with multi-multi super expensive multimillion dollar equipment, that's super delicate, fragile. And you're thinking about the consequences of a tear in the suit at one point in the book. How do you even decide what to worry about when pretty much everything up there is lethal?

[00:49:58] Mike Massimino: Yeah, I think, you don't want to worry about anything. You want to have confidence in your suit and just go about your work, but you also want to be very careful. You just want to operate very safely. You don't want to cowboy or anything, or be cavalier about the way you're moving around to doing things because that leads to trouble. You just turn into this sort of mode of operation, where you try to be very professional, very precise, everything you say that comes out of your mouth, you want to be very, very precise about what you're doing, what you're reporting, what you're asking. Every time you move, you're moving with a purpose. You always know where your tethers are. You're not going to lose anything. You're not going to lose yourself. You know exactly what you say to each other — everything, every piece of equipment, everything that's on you. You have this total consciousness of what you're doing.

[00:50:40] And in that way, you know, you're operating in a very efficient way. That'll give you the best chance of being successful, but also in a very safe way to give you the best chance to come back inside. And you have to trust the equipment that it's going to work. When you get into your space suit and you seal yourself in there, you got help from your friends and you know, your buddies are checking everything. And you got people on the ground watching and making sure everything's going okay, as best I can. And that's what you're doing. You try to operate very safely.

[00:51:05] But still even with that, at the end of my second spacewalk, I found out there was a slight tear in my glove. And if it was something that we had noticed at the beginning of the space walk or anywhere before then, it would have probably created us to terminate the spacewalk—

[00:51:17] Jordan Harbinger: Oh man.

[00:51:18] Mike Massimino: But because it happened toward the end and we were coming in any way, there's really not much we could do about it, but luckily it didn't affect anything that day. So it made me realize that a little bit closer to the edge and I wanted to on that one.

[00:51:29] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, no kidding. This suit, it seems like if you accidentally made a little tear in it, what are these things made out of that that can kind of accidentally happen? It sounds like there's a lot that can actually go wrong with the suit. And I assume you can't just throw some duct tape on it and go out there anyway.

[00:51:45] Mike Massimino: No, the thing you want to prevent from being compromised is the inner bladder of the suit because the suit has seven layers to it, including a layer of Kevlar. The part that is more vulnerable is the gloves, because the gloves don't have that layer of Kevlar because then it can't be too stiff.

[00:52:03] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:52:03] Mike Massimino: And the Kevlar just protects mainly from an impact. And so it's in other parts of the suit, but the glove gets a lot of wear and tear. And so the material on the outside, which is pretty tough, can get worn down over time. And if a little cut develops, it could cut the outer layer. Now, I still have a lot of layers inside protecting man. I still had the bladder on the inside, but as you start wearing through those layers, you start exposing the more critical layer. So the outer layers, you can take a cut in and survive. But what you've done is you start exposing the inner layer and it's the pressure bladder. It's like a rubbery pressure bladder inside that keeps your pressure, keeps your air, the atmosphere inside of your suit intact. You can take a hit or a cut or a scratch in the material on the outside, as long as it protects the pressure bladder, but what I can say to my case is that we had gone through the outer layers and that we were going to get closer to that pressure bladder. And that's why it would have been a situation where you'd have to stop if it hadn't been discovered earlier.

[00:53:01] Jordan Harbinger: Got it. And so right before you're about to leave the shuttle and go on a spacewalk. Are you kind of nervous at this point? Or are you thinking, "Hell man, I'm already in space. Like we're already here, let's just do this."

[00:53:12] Mike Massimino: To me, it was a huge difference going outside because we were in a spaceship and it's kind of like you're in a room, sort of. You're in this room, inside of your cabin, on the ground. And then you're in space, but you're in space when you're still inside the cabin. You've gone far away in the cabin, but you're still inside. It's like being in an airplane, now you're still inside the airplane, as you're flying around. And when you're looking through the window of the spaceship, it's kind of like looking at the fish in an aquarium and looking through a window. But when you go outside, out in space, now all of a sudden I really felt like I was outside. I was in space. And it wasn't looking inside of this room and through a window anymore, it was looking anywhere I wanted. And it was really nothing around you. I mean, even when you're outside on earth, you have the sky, you know, you see the stars, you have the sky above you or clouds, but when you're out in space, there's nothing there. Just stars, you know, it's just openness.

[00:54:00] This idea, I really felt like I was outside. I really felt like a spaceman. It was a much different feeling than being inside of the cabin and much more beautiful view as well. And you can look anywhere you want, and you could really experience the brightness of the sun and the darkness of the, when you're not in the sun. And you can feel the temperature change and you can look out and see things without being constrained by a window, or look at the stars and in turn your head and look at the earth. The altitude we were out at Hubble's a hundred miles higher than the station where the Space Station flies. It was at the ceiling of where the shuttle could fly. And you could see the curve of the planet. You can see the roundness of it, which is extraordinary.

[00:54:37] Jordan Harbinger: How clear are the stars without the atmosphere that must've just been a total game changer? I mean, you're already looking at pictures of space. You're looking at the stars a lot. I would imagine as a kid and then you're up there. There's nothing between you and those things.

[00:54:50] Mike Massimino: Yeah. Perfect points of light. So the reason stars twinkle on the ground is because the light comes through the atmosphere and gets a bit distorted and they twinkle, but there's no twinkling. There are perfect points of light when you get above the atmosphere and you see them directly. You're not any closer to them, but they're just a lot clearer. You can see different colors in the stars and they don't twinkle. They're just these perfect points of light everywhere.

[00:55:12] Jordan Harbinger: What about space sickness? I wondered if you're in a boat. You're going back and forth. You get a little seasick. Is there space sickness or is that not a concern?

[00:55:20] Mike Massimino: No, it's space sickness for sure. Throughout my first day in space, I was over by my second day and my second flight I wasn't affected at all, but my very first day in space, I was motion sick. I was kind of, okay, I got everything done. But at the end of that day, right before bed, I tried to drink some water and it came right back up and I wasn't feeling well. I was happy to go to bed. Then I can get a good night's rest and wake up the next morning, feeling much better, but it's a conflict of your sensory inputs. Your vestibular system on earth when you're moving around in a boat or a car to get motion sick. It's because it might be elicited. Particularly, if you're looking at it. If you try to read something and your eyes are telling you, you're perfectly still, and your inner ear is being accelerated, bounced up and down in a car or a boat or whatever. That's what leads to sea sickness, motion sickness.

[00:56:04] In space, your vestibular system, which works on gravity is not moving at all, is telling you perfectly still, but yet you're moving around. Your eyes can say, you're moving. And that leads to the same sort of effect. And what happens is the brain gets smart about this and eventually will stop listening to the vestibular system because it's not working any longer and then you're fine, and then you don't get sick anymore.

[00:56:24] Jordan Harbinger: That's amazing how the human body can adapt to space just within a few days. I mean, that's so impressive.

[00:56:30] Mike Massimino: Yeah. The brain is an amazing thing. And the whole system, our body is able to do some amazing things in getting ready.

[00:56:36] Jordan Harbinger: So you're repairing the Hubble, saving humanity, the future of humanity, right? The special forces of NASA over here, 650 grand an hour is a mission cost, but you still got to be doing some horsing around up there, what was the most fun you had? And I'm not talking about the PC answer. Like, "It was really rewarding saving the Hubble program." What's the fun stuff that you guys are doing up there? Especially when the missions are over and you're just decompressing.

[00:56:59] Mike Massimino: Looking out the window, listening to music, and just taking in that extraordinary view was something I could do forever. For me, that was the best way to decompress and just to enjoy the time up there and enjoy that view. Magnificent!

[00:57:11] Jordan Harbinger: Are you able to stay clean up there physically? Or is it just kind of like wipe your armpits with a wet nap and wait until you get back to earth?

[00:57:19] Mike Massimino: No, it's pretty good. It's just like taking a sponge bath. You have a liquid soap that you use and waterless shampoo, and you know, you don't really have running water for a shower, but you're able to take a sponge bath and stay fairly clean. You're ready for a shower when you get back for sure.

[00:57:33] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I bet there's certainly a lack of water. I mean, that stuff is heavy and you're bringing plenty of it in your body. As you said in the book, "Today's coffee is tomorrow's coffee," right?

[00:57:43] Mike Massimino: Yeah, that's the way it is on the Space Station. It's recycled. On the Shuttle, we had fuel cells that generated water as a by-product of the power that they generated, but on the Space Station, yeah, they recycle all the water. So today's coffee is tomorrow's coffee.

[00:57:57] Jordan Harbinger: What does it feel like to readjust to earth after you land? I mean, what did you do first and what did you miss most in space besides of course your family?

[00:58:06] Mike Massimino: Yeah, I miss, of course, as you said, my family and friends, and I miss things like just going to a baseball game. I was looking forward to the baseball season starting. Both of my flights had flown in the spring and I was looking forward to that. Pizza, looking forward to just grabbing a pizza and just watching TV and vegging out. And people just being around a lot of people. Just being around normal sort of normal stuff. I think that when we landed a few days after I landed, my son was a swimmer and he was on a local neighborhood swim team. And these swim meets were on Saturdays and all the parents would be there sitting in their lawn chairs under these kinds of tents, like structures and getting the kids ready. And it was always a crowd of people, just a lot of kids and a lot of parents and coaches and all this activity with the swim meet, lots of people. And I really enjoyed those things. And that's what I miss. Being around a lot of people at a big family or community event for me was something I looked forward to. Those swim meets look forward to going to baseball games, eating pizza, using a real toilet and sleeping in a normal bed.

[00:59:07] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I can imagine sleeping in a bed that you won't float off of or away from probably in taking a nice little shower as well. What was the strangest thing about readjusting back to earth? You mentioned at one point you dropped a bag of groceries because you just let it go in mid-air thinking it would stay there.

[00:59:23] Mike Massimino: Yeah. You kind of forget where you are or you get used to it, you know, in space, just float and stuff. And then you get back to earth and that doesn't work as well. It doesn't work at all. And yeah, so I had that experience where I was taking a bag of groceries out of the car and didn't know where to put it. So I just reached back and put it up high and then let go, like it was going to float right there. And of course it just crashed to the ground. But yeah, you're like, dang gravity is terrible. I think also you're so focused on the mission and you focused on the mission and training and get her ready for it and then executing it and being up there. And then all of a sudden it's over. You know, this thing you've been thinking about for years is now over and it's time to figure out what to do next.