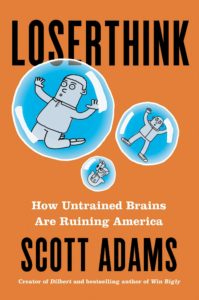

Scott Adams (@ScottAdamsSays) is the creator of comic strip Dilbert, a talent stacker extraordinaire, and bestselling author. His latest book, Loserthink: How Untrained Brains Are Ruining America, is out now.

What We Discuss with Scott Adams:

- Why the term “loserthink” isn’t about being uninformed — it’s about unproductive thinking.

- Mental models we use that sometimes fail us, and thinking traps that we fall into when we’re looking to interpret communication, evaluate facts or evidence, and form opinions.

- How to evaluate fake news and see why the business models of many media outlets have been redesigned to keep us engaged at the expense of accuracy and truth.

- When and how to dial down our ego so we can clarify our thinking, and also when and how we can use our ego as a tool to move forward.

- Ways to evaluate and poke holes in bad arguments, and strengthen our own methods of thinking and arguing.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

On this episode we talk to Scott Adams, Dilbert creator and author of Loserthink: How Untrained Brains Are Ruining America, who always brings fascinating (and often controversial) discussion to the table. We dig into what Scott means by the term “loserthink” and how we can spot it in others while avoiding it in ourselves, when ego isn’t our enemy, how to poke holes in bad arguments, how to spot fake news, failing mental models, and much more. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll down for Video, Featured Resources, and Transcript!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

On No Dumb Questions, a science guy from the deep south (Destin of Smarter Every Day) and a humanities guy from the wild west (Matt Whitman of The Ten Minute Bible Hour) discuss deep questions with varying levels of maturity. Give No Dumb Questions a listen here!

THANKS, SCOTT ADAMS!

If you enjoyed this session with Scott Adams, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Scott Adams at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Loserthink: How Untrained Brains Are Ruining America by Scott Adams

- Other Books by Scott Adams

- Dilbert

- WhenHub

- Scott Adams’ Blog

- Scott Adams at Periscope

- Scott Adams at YouTube

- Scott Adams at Twitter

- People Are Worrying That Kanye West Is Getting Radicalized By The Far Right, BuzzFeed News

- The Kristina Talent Stack, Scott Adams’ Blog

- On the Promotion of Human Flourishing, PNAS

- Stock Market Performance by President, Macrotrends

- Elon Musk’s 6 Productivity Rules, including Walk Out of Meetings That Waste Your Time, CNBC

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy, You Are Not So Smart

- Malcolm Gladwell | What We Should Know about Talking to Strangers, TJHS 256

- Friends

- I Wish Drucker Never Said It, Great Things That People Love

- A/B Testing, Wikipedia

- The 48-Hour Rule, Charlottesville, Prison Reform and CNN’s Swastika Get, Coffee With Scott Adams Podcast Episode 174

- What Was the Point of the Syria ‘Withdrawal’? The Atlantic

- Scott Adams: Third-Rate Politicians, Sharing All That Syrian Sand, The Hypnosis Coup, Coffee With Scott Adams Podcast Episode 696

- Newscompare: Get the Real Story and Filter the Spin with Side-by-Side Comparison of the News

- Why Scott Adams of Dilbert Fame Risked His Reputation by Sparking Controversy in the Election, The Washington Post

- Why Libertarians Are (Still) Plotting to Take Over New Hampshire, Mother Jones

- Little China in Belgrade, BBC News

- Word-Thinking Replaces Thinking in America, Scott Adams’ Blog

- Family Guy

- Slate Star Codex

- Tesla

- Grand Canyon Stunts Over the Years, National Geographic

- 2018: The Year of Dog Whistle Politics, The Washington Post

- Laura Ingraham’s Anti-Immigrant Rant Was So Racist It Was Endorsed by Ex-KKK Leader David Duke, The Daily Beast

- DeSantis Warns Florida Not to ‘Monkey This Up,’ and Many Hear a Racist Dog Whistle, The New York Times

- 14 Things People Think Are Fine to Say at Work — but Are Actually Racist, Sexist, or Offensive, Business Insider

- The Bait-and-Switch Confusopoly Economy, Scott Adams’ Blog

- You Can Cut a Better Deal on These 9 Bills, NerdWallet

Transcript for Scott Adams | How Untrained Brains Are Ruining America (Episode 273)

Jordan Harbinger: [00:00:03] Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. As always, I'm here with producer Jason DeFillippo. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most brilliant and interesting people and turn their wisdom into practical advice that you can use to impact your own life and those around you. I just want to help you see the Matrix when it comes to how these amazing people think and behave, and help you become a better thinker as well.

[00:00:25] And today on the show Scott Adams, creator of the Dilbert comic strip. He's been on the show before and he tends to pop up in random places. I saw Kanye West talking about him once online. That was an interesting morning. His new book is called Loserthink: How Untrained Brains Are Ruining America. The book and our conversation today is about certain mental models we use that sometimes fail us and thinking traps that we fall into when we're looking to interpret communication, evaluate facts or evidence, and form opinions. Today, we'll learn how to evaluate fake news and see why the business model of many media outlets has actually been redesigned to keep us engaged at the expense of accuracy and truth. We will also learn when and how to dial down our ego so we can clarify our thinking, and also when and how we can use our ego as a tool to move forward -- it's not always our enemy. And we'll discover some ways to evaluate and poke holes and bad arguments and strengthen our own methods of thinking and arguing.

[00:01:24] If you're wondering how I get guests for the show, well I've got a great network and I'm teaching you how to build networks for personal and professional reasons over at our free course Six-Minute Networking. I created that; there's no sort of weird catch. There's nothing to buy. It's just a free course on networking for business or personal relationships. Go to jordanharbinger.com/ course and check that out there and I'd love to hear what you think. By the way, most of the guests on the show actually subscribe to the course and the newsletter. So come join us and you'll be in great company. All right. Here's Scott Adams.

[00:01:56] So, Loserthink, great title, by the way, I'm sure that's one of those where people think, "Ah, I do that. I'm going to pick that up."

Scott Adams: [00:02:05] I think everybody has a different idea of what I mean by it. I usually have to explain that what I mean is not the person is a loser, but rather the technique of thinking about things in a certain way can take you down a losing path. I try to show the bad examples and then how to fix it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:02:21] I was just using your idea to take a photo of this page of the book when someone engages in loserthink. Show them the page that it's from and it will take emotion out of the equation. I will tell you it definitely worked for me to take emotion out of the equation, but it did receive some emotion in return in the form of somebody who doubled down on their loserthink and decided that I was just being an ass.

Scott Adams: [00:02:48] People don't like to be shown that they're wrong, but you have to admit that showing them a printed book that somebody thought was worth publishing gives it a little bit of unearned credibility.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:02:59] Yeah. Well, it's better than saying "Here's everything that's wrong with your thoughts." And then they go, "I don't like you. So now I'm going to poke holes in that." It is just like, "You should read this page and find out what is objectively wrong with your line of reasoning."

Scott Adams: [00:03:11] Yeah, if you're doing it on Twitter, normally you can't fit like a half a page of explanation in there, so you're just, "Hey look at this photo."

Jordan Harbinger: [00:03:18] Here's an image, because I didn't feel like typing out all the reasons that you're wrong. Yeah. So loserthink isn't about being uninformed. It's about unproductive thinking, right?

Scott Adams: [00:03:28] Yeah, specifically where it comes from is people are not necessarily exposed to the different fields and domains where people think in certain ways. For example, let's say you went to college, you got a four-year degree, but it was in art history. Would you have the same tools to compare things and, you know, figure out what things will cost over time and to know whether you've got a rational comparison compared to say, someone who studied economics or somebody who went through law school or perhaps an engineer -- just examples -- scientist? There are some fields where people learn how to think productively and the problem is if you don't study that stuff, you think you can do it because you think your common sense is all you need. You can see in five minutes on Twitter that that's clearly not the case.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:04:17] Oh, yeah. I mean, I don't know if you knew this, but the listeners often do, I studied economics and have a law degree and was a practicing lawyer and I still have trouble parsing arguments really quickly. I have to look at things and read them, which is actually -- go figure -- what you're supposed to do as an attorney. A lot of people think, "Well, I'm a lawyer and I can just tell you that this is wrong because I have all this stuff memorized," and that's not how it works at all.

Scott Adams: [00:04:40] So you're actually a perfect example of the talent stack idea. If you put together the right combination of skills, you've got something that's like a superpower. I'll use you as my example. I can't think of many things that would be more useful in the modern world than a knowledge of economics, law, and then what you're doing here, communication -- from the technology to the whole process of it. That's a really powerful stack. It also gives you the ability to look into different windows. I like to use the house analogy, you know, when I was 19 and somebody said, "Hey, tell me what's in that house?" I would walk up to the bathroom window and look in and say, 'Well, it looks like this house is a big old bathroom.' That's the only window I could see, but then I studied economics. I became a trained hypnotist. I learn communication skills as part of my job. I just started stacking things so I can see in more windows and that's what I'm trying to help people with with Loserthink.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:05:37] I love the idea of the windows. I'm trying to think of an example here, but if you look at somebody who says, "Well, this problem is clearly this, because, from a soil science standpoint, all of these things are horribly, horribly wrong." It's like, maybe we're looking at this from a human flourishing standpoint where these people don't have electricity. So yes, it's bad for the soil, but what's really bad for these people who live there is the fact that they don't have clean water because they don't have electricity.

Scott Adams: [00:06:06] It sounds sort of close to what I call the one-variable problem. If you're talking about a complicated thing, whether it's climate change or the economy or world events, and somebody boils it down to that one thing that matters, you can ignore everything they say. Because if your worldview is down to, "Well, it's just this one thing. If you understand this one thing, you know everything you need to know." That person probably doesn't have a wide base of understanding of the world. The one variable tell is the one that I look for the most often is like, "Well, it doesn't look like you've looked into this or you don't have the tools to look into this productively."

Jordan Harbinger: [00:06:41] Yeah, so we really do need a broad set of skills and diverse thinking, and I think a lot of people don't necessarily have that. I certainly, even with my broad set of skills and diverse thinking, realize even more that it's not impossible, but very, very difficult to be sure about something. And that certainty is dangerous, because if you look on social media, people are sure about everything.

Scott Adams: [00:07:03] Yeah, if you have certainty about a complicated issue, that should be a little signal that maybe you should back that up a little bit. Maybe you should have a little less certainty, a little more humility, and that's something I talked about as well. Now it's important to note that you don't have to get a degree in every field to get the basics of how people think in different ways. For example, if I ask somebody on Twitter, "Hey, is this president or that president doing a good job -- or did a good job?" People have a firm opinion. But if I asked a scientist, they might say, "Compared to what?" Because the scientist, the economist, the business person, a lot of other domains would say, "Well, you can't really tell anything until you've compared it to something that is a sensible comparison." In presidents, you can't really compare one to the one that was the last one, because it was a whole different situation. The only valid comparison would be if you magically had another president in exactly the same situation at the same time doing the job in parallel, then you can see which one was getting better results. But of course, you can't, so if you have certainty that your president has done a good job or a bad job, I'm not sure that certainty is warranted. I mean, there are some big things you can look at say, "Well, he didn't break the economy. He didn't start a war," but after the big stuff, it gets really subjective after that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:08:25] Yeah, that's a good point. And also with economics, I think a lot of people don't realize these things, they come in decade- or multi- -decade-long cycles. So people will go, "Oh, well, look how good it was that this two-year period." It's like, "Well, is that from the current administration, the previous administration, or one that came so far before that that we built infrastructure for whatever you're enjoying now?"

Scott Adams: [00:08:48] So the perfect example is people will say, "Hey, President Trump is doing great things with the economy. It's never been better." His critics will say, "Well, Obama got the base going." And in fact, if you look at the percentages, you know Obama increased things faster than Trump did. Now if you don't have a background in economics or business, you'd say, "Huh? Pretty good point. That last president increased things by a bigger percentage; that must be better." If you do have a degree in economics, or at least if you've been exposed to a little bit of how to think about this stuff, you'd say, "Coming off a near-depression, when everything's at the lowest level, you would normally expect big percentage gains." Because, for example, the people who were out of work are fully trained. So the moment the factory says, "Hey, we got a job for you," you walk right and you're fully trained, you're ready to go. So the first gains should be the easy ones. Once you get to the end of an improvement, you've got the really hardcore, hard-to-employ people. We're down to 3.5% unemployment. If you're in that group, maybe you're just, you know, you're just between jobs. But it's far more likely you have a hard time getting employed because you're not trained for the jobs that are available. If you can make any kind of economic gain under the hardest of conditions, which is when you're reaching a top, that's worth a lot more than big percentage gains when you're getting the easy stuff coming off the bottom.

[00:10:15] Now having said that, I always credit Obama for being probably the right personality at the right time, because everybody was panicked about the economy and he was that calm, smart, professorial person who said, "We got this. We'll do this. We'll do a few things. We got this." I do think he was sort of perfect for the situation. If you'd have thrown a President Trump into that situation, maybe you've got problems, because he's a little more unpredictable and people maybe are not as comfortable. But he came in when the economy was already solid. Thank you, Obama. And once the economy is solid, what would the people who study finance, business, economics, risk management -- what would they say you should do? Take a little more chance. Who's a better personality to give a little more flavor, a little more chance, a little more maybe a more upside potential with some risk? The right time to do it is when the economy is strong, and we saw Trump come in and do the riskiest thing you've seen a president do, which is challenge China on trade. And it's worked out fine, because the economy was strong enough, it just sort of absorbed that little bit of a shock. People thought it would be a bigger shock. So when you're looking at situations like this, a little bit of economics background completely changes what you think about it, whereas the music majors and the art majors are looking at the percentages and saying, "I know Obama had a bigger percentage gain than Trump. He must be the good one."

Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, it is easy to look at stats and get confused, especially when those statistics are designed to -- not every statistic but many -- are designed to trick you into thinking what the person telling you those stats wants you to think in the first place. If I want to show the economy's better under a certain administration, I will pick the figures out that are the most favorable. Look at the unemployment rate right now. Look at the amount of disposable income people have. "Well, that looks good. So I guess we have a great economy." Someone will also go, "Look at the amount of crime or look at the sheer numbers of unemployed people as a relative percent." I mean, you can just pick anything that you want. And so people who have high levels of certainty in very, very complex situations, especially if they're not trained in those fields, that's what you would call loserthink, right?

Scott Adams: [00:12:31] Yeah, and people who have experience like I do, which is for years in my day job in corporate America, I was supposed to do financial projections. People who see it from the outside say, "Oh, these experts are making these projections. I guess that's pretty reliable. They're experts; they're making projections." But if you've done it for a living, you know it goes like this: "So, boss, how do you want these numbers to come out?" "Well, I'd like it to show that this is a good idea because we've already bought the equipment." "Okay, I can make that happen." I go back to my desk and sure enough, these numbers look great. And then you take that to your boss' boss and you go forward. Now that doesn't mean it was a bad decision. I'm just saying that if you have experience rigging numbers, you don't really trust anybody else's numbers from that point on.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:13:15] Yeah, that makes sense. It's like people who create commercials probably read a lot of reviews about products before they buy anything.

Scott Adams: [00:13:23] Probably.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:13:24] So loserthink as a word, it's mockery, right? Is that up for debate at all? It sounds mocking.

Scott Adams: [00:13:30] It is mocking, and that's intentional. Because if you can label somebody's behavior as loserthink, putting a word on things gives it power that it doesn't have as a concept that has to be explained. The best example I give that in Loserthink is that when Elon Musk wanted to explain to his staff what they should and should not do corporate behavior-wise, he simplified it by saying, "Don't do anything that would appear in a Dilbert cartoon." Now the beauty of that is everybody kind of knows what that is without having to have a thousand examples. You know it when you see it. "It's like that could have been in a Dilbert cartoon." So that was a handy thing he could do based on the fact that there was one word that everybody understood. So by introducing loserthink, I'm kind of collecting a bunch of bad thinking techniques so that people can mock it more easily.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:14:19] So mockery is useful because it basically shames unwanted behavior.

Scott Adams: [00:14:25] Mockery is one of the most powerful forces in civilization. Nobody wants to be mocked in public because it reduces their power, their influence, their ability to mate. I mean, it's just the most basic human thing is You don't want to be mocked. You want to be the good one in the room. It's a weapon. It's a tool. And I hope people use it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:14:42] Yeah, not just calling someone a moron, of course, but showing them how and why their thinking is wrong is more powerful. It's easy to insult people, but it's also really transparent because then it kind of goes, "Oh, yeah, that guy's a moron." "Why?" "I don't know, but it was funny for five seconds." So it really doesn't persuade as much.

Scott Adams: [00:15:00] With loserthink, you want to be able to show people what they're doing wrong, but I've tried to keep it simple. For example, it's something you could hear once and say, "Oh, that makes sense." One example would be the concept of sunk costs. If you're an economics person, you know that money you've already spent, that's called the sunk amount. It shouldn't affect your future decisions. Now anybody who studies economics just understands that as just a rule of the universe. It's already gone. That money can't be brought back. So the decision you make today about continuing with the project should never say, "Well, we've already put this much money into it. We don't want to waste it." It's gone. The economist knows it's gone and it can't come back. Now, the power of that is that you hear that for the first time, like you're explaining it to somebody who never heard the concept of sunk cost, they don't need to go read a book about it. Well, you hear it once and it becomes part of who you are. You're like, "Okay, that makes sense."

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:55] Yeah, these concepts, these fallacies, and these different models of thinking are something that I've got plenty of notes on here that I want to dive into soon, as well. And this show is largely about freeing people from what you call mental prisons. I want people to question everything. I want people to especially question the things they already think they know and the things that they believe, because those are the most dangerous paradigms that you have are things that you already quote unquote know to be true and turn out not to necessarily always be the case.

Scott Adams: [00:16:24] Yeah. That's why one of the things I recommend is that you keep a mental list, or even write down, when you got a prediction wrong. Because we're always going through life with either formal or at least casual predictions about what's going to happen next. When you're wrong, take note of that. The way we're wired is we forget our mistakes and we remember our accomplishments, except for the bad mistakes, I suppose. But it's really easy to make a prediction, be wrong, and then immediately wash that in your memory bank, so it's not part of who you are anymore. I say keep it, value it, because that told you something. There was something wrong with your mental models, your ability to predict that got that wrong, so make a point of remembering when you get it wrong.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:17:08] You mention the business model of the news has changed. Let's talk about this, because this affects everyone's thinking and makes it less accurate. Whereas people think they're becoming more accurate because they're becoming more quote-unquote informed, but they're just learning these negative patterns of thought. It kind of reminds me of -- Malcolm Gladwell wrote about this -- the Friends principle, where we think we can read emotions really well because we've all seen Friends, except for their emotions are completely overblown, exaggerated, fake. We think, "That's what people look like when they're surprised." That's just a caricature of a surprised person. News is doing this for us, becoming more informed and having critical thinking. We think we're working on this skill, but really we're just going, "Oh, this bottle of Tylenol got recalled. Maybe all the Tylenol is poisoned and the government is out to get us and it's from the Chinese secret intelligence services. They are poisoning all of our Tylenol." So it just results in us being ridiculous and being more uninformed or less informed than we ever were with the TV off.

Scott Adams: [00:18:05] Yeah, the big problem that made everything bad in the news world is when technology got us to the point where we could measure with great specificity, real precision, what works better than another thing to get attention, get clicks. Once you could measure it, it was done. Because there was only one way that was going to go. People have responsibility to their stockholders, their bonuses depend on profits, not informing people. Like there's no metric that says, "Well, you're the head of the news network. How many people did you make smarter?" Nobody's measuring that. So a truism of the business world -- again, this is if you have experience in the business world, this is just obvious. Not so obvious if you've not been in it -- and that is: what is measured is what is managed. That rule, if you don't remember anything else about the practice of management, you could actually go pretty far. That's like half an MBA I just told you right there, right? If you can measure it, then you'll probably manage it. If there's no way to measure it, you're just not going to. The thing that could measure is how excited people got because they clicked. And once they could figure that out, they could say, "Well, let's try this slight variation," and they could just A/B test it -- that's what it's called: A/B testing -- until they could figure out the very best way to light your hair on fire, and that's usually with something that's closer to fake news and rumor mongering than it is to factual stuff.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:19:30] Yeah, you see headlines now even in -- I hate using air quotes, but I'm going to do it again -- even in "reputable" sources, you'll read a headline and if you ever see comments sections, people will be annoyed that this headline is totally misleading and it'll be like, "One-third of kids getting no nutrition at school," and you're just thinking, "Oh, my God, they're not feeding kids at school." And the truth is they're just not getting, like, enough folate in their beans. And it's like, "Wait. What the hell? This isn't news. This isn't a news story." Some beans in some schools don't have enough folate and it's a complete non-issue because you get it from like, I don't know some other multivitamin that you take in the morning.

Scott Adams: [00:20:08] Yeah. That's what I call the 48-hour problem, which is most of our news gets overturned 48 hours later. Because the first version, and indeed the reason that it became news at all, is that it was unbelievable. And there's actually some science behind that. The news that really gets your attention is the stuff that's not true, usually. I mean there are exceptions. And the reason that gets your attention is because, in the real world, this couldn't really happen. So people are like, "What? Somebody ate a baby on live TV? I can hardly believe it!" 48 hours later, "Well, they didn't eat a baby. They were talking about babies while they ate their lunch," and you find out your whole worldview just disappeared in 48 hours. And I would say that's almost universally true of anything in politics today, that 48 hours later, the other side is going to say, "Here's the context you left out," and it really will be important context.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:21:00] So we should follow this 48-hour rule and what, not get all upset, or not get turned upside down, or not react within 48 hours? Just wait for the next 48 hours?

Scott Adams: [00:21:10] Well, you know, if you're in the news business, you have to cover the news. But for the citizens watching it, just reserve judgment for 48 hours and especially if bullets are flying anywhere. As soon as bullets are flying, the truth just goes right out the window. When the whole Syria withdrawal thing came out, I predicted in advance, to my Periscope people, "Okay. Here's what's going to happen. You're going to see fake deaths. You're going to see fake babies dead. And you're going to see claims of nerve gas used." You know, it's all the basics. Because if you're the group that might get wiped out by a superior military force, you're going to use every tool. There are no rules in wars like this. So, of course, they're going to try to influence things with fake news that makes their side look good, which is not to say those things don't really happen. Kids got killed, probably there were weapons we wish had not been used, but I don't necessarily trust the stories. Those might be manufactured.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:22:09] So the individual anecdotes might not be true. Although to be fair, I have a friend in Syria right now right there who is managing some humanitarian stuff and it's ugly. I don't know if they're using nerve gas, but you wouldn't want to be hanging out in Western Syria or Eastern Syria.

Scott Adams: [00:22:24] That's practically my mantra. I don't want to be hanging out in --

Jordan Harbinger: [00:22:27] In Syria? Just generally? Yeah.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:22:32] You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Scott Adams. We'll be right back.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:22:36] This episode is sponsored in part by Xero. We've been using Xero for years here. It's cloud-based accounting software and we actually went after them to sponsor the show. It's super-fast, super intuitive, really easy to use. It's a pleasure to use. Jen loves doing it. And for people to hate the idea, they have to do accounting at all, Xero makes the process very painless. A lot of small businesses medium-sized businesses are using this as well. For any online components for your business, I would highly recommend it. It uses multiple currencies with no problem. It has an unlimited amount of users. So you're not just handing out logins to your interns and your accountant and then something goes wrong and you can't tell who did. You can also work with any kind of expert that you need and just throw them a log and that's a major benefit that I find here. You can also pay month-by-month. You're not locking yourself into like a 12-, 18-month contract. A lot of software will make you do that and they have 24/7 support so you can mess up all you want and be good to go by Monday. They are a New Zealand company, good people out there. You can also view things from your iPhone or Android app which helps when you got to check your dashboard in an Uber on the way to the airport, you know, we're all doing that. So try Xero risk- free. Jason, tell them where they can get a deal on Xero.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:23:48] Try Xero risk-free at xero.com/jordan. That's zero with an X, X-E-R-O xero.com/jordan for a free month and 25% off your first three months at xero.com/jordan. You'll thank us later.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:24:03] This episode is also sponsored by Everlane. A lot of brands talk about making the best basics. It's kind of a trendy thing nowadays yet. They disappoint the fit sucks. They're too expensive. They stretch out. They shrink in the wash. They fall apart after two months. So you just buy new ones you start the process all over again. You've relegated yourself to just being permanently disappointed, but that's why you need the uniform by Everlane. This is a collection of men's basics that actually last. They look and they fit great. I love these things. They're like high-quality t-shirts, V-neck, crew neck, whatever. They're cut right. They fit really, really well. They have classic tees, four-way stretch denim. Each uniform item has been rigorously tested to simulate a full year of washing. I hope they don't just wash those things like 50 freaking times, but who knows. They simulate the washing in a way to make sure it holds up to everyday life and it's backed by a 365-day guarantee. That literally means you can wear it for a year. Hopefully, not every single day and if it falls apart, you can get a new one from Everlane which is amazing. So I've worn these things like crazy, throughout the past couple of weeks. I've traveled, I've washed them a bunch. They look new which is kind of impressive so far. I mean really impressive so far and the price is definitely comparable to super expensive stuff that definitely doesn't look new. Jason, tell them where they can get a deal on Everlane.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:25:19] Get free shipping on your first uniform order at everlane.com/jordan. That's free shipping on the most comfortable basics, you'll ever wear only at everlane.com/jordan. That's everlane.com/jordan.

[00:25:31] Thanks for listening and supporting the show. To learn more and get links to all the great discounts you just heard from our amazing sponsors, visit jordanharbinger.com/deals. Don't forget we have a worksheet for today's episode, so you can make sure you solidify your understanding of all the key takeaways from Scott Adams. That link is in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast. If you'd like some tips on how to subscribe to the show just go to jordanharbinger.com/subscribe. Subscribing to the show is absolutely free. It just means that you get all of the latest episodes downloaded automatically to your podcast player, so you don't miss a single thing. And now back to our show with Scott Adams.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:09] How does the 48-hour rule benefit all of us and not just politicians and celebrities? Because of course, in the example in the book, it's like, "This person did this. I'm not a Kardashian. I'm not running for president. Why should I care about whether this is going to blow over in 48 hours?"

Scott Adams: [00:26:23] Well, we all get locked into our first opinion. Being human, if you form an opinion, you just don't like to ever modify it. I mean we do sometimes, but it's rare. So if you hold off for 48 hours, chances are you'll get to form an opinion that's based on something a little closer to the proper context at least. If you want to be an informed citizen and play a productive role, wait 48 hours on the big stuff.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:48] It sounds like what you're saying is because, if we get an opinion right away based on this one bit of information that may be overturned in 48 hours, we have to work that much harder to overturn our previous or previously -- what do you call it when cement hardens?

Scott Adams: [00:27:04] You're sort of locked in.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:27:05] Right, you lock in. It's like coagulated by that point. Your opinion has clotted and it's harder to shake it loose, and that's not good if you want to have an equal chance of getting all the proper and correct information into your system.

Scott Adams: [00:27:19] And one of the techniques that I recommend, and it seems incredibly obvious -- except people don't do it -- which is you just have to sample the other side's new source. It doesn't matter which side you're on. If you're watching mostly CNN, you have to watch a little Fox News to get their side of it. Whether you think it's true or not, you've got to hear what they're saying and vice versa. I have a little rule that I talk about in Loserthink, which is that if both sides -- the left and the right news business -- if they say a fact is a fact, well it's probably a fact. It might not be, but probably. But if one side says it's a fact, then the other side says it's not, and they're looking at exactly the same observation, it's probably not -- and "probably" meaning 90% chance not true.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:28:05] Although I suppose if the news business is engaged in getting us all worked up over nothing, and then they both agree on something, it's probably still exaggerated, right?

Scott Adams: [00:28:13] Well, yeah, you never know how much is exaggerated when you're sort of on the outside, but yeah. At least if you can get them both to agree, it's a fact. That's something.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:28:22] Right. Maybe there is a hurricane coming -- pack your stuff and get out of there. Whether or not it's going to be as severe as they all say, I don't really want to find out by being the first person to get blown off the roof of my house. A lot of people think they can read minds and see what other people are thinking. Now they don't frame it like that. They don't say, "I can read minds. I know what you're thinking." They just go, "That son of a bitch. He is doing this, this, and this, and is racist on top of all that."

Scott Adams: [00:28:47] It happens to me literally every day.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:28:49] It does happen to you a lot on Twitter.

Scott Adams: [00:28:51] It happened to me this morning, and I took a picture of my own book, the section on don't be a mind reader, and tweeted it to him. I don't think it helped in his case, a hard case. But I think in this case, somebody was saying on Twitter that my real motive was lying to people to make money about politics.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:29:09] It's working. You have a really nice house.

Scott Adams: [00:29:12] I must have been lying really good. To which I say, "Talking about politics cost me a third of my income and it's not coming back."

Jordan Harbinger: [00:29:20] How so? Just from losing speaking gigs or something like that?

Scott Adams: [00:29:24] Yeah, speaking gigs, licensing, just my normal business decreasing. If I put out a Dilbert book today, 40% of the country is going to say, "I don't like that guy because he said something about politics I didn't like."

Jordan Harbinger: [00:29:35] Yeah, so economically it's not working out for you to be such a loudmouth on Twitter or Periscope.

Scott Adams: [00:29:42] Yeah, that's correct. I made a conscious choice that there are only a few people in the country, probably just a few, maybe a handful, who would be willing to say something deeply unpopular and take the blowback if they believed it to be true. And I have, as I like to refer to it, "FU money," meaning that I can lose the third of my income and I'll still have a good life. There aren't many people in that situation, so your average wage-earner is not going to be honest in public. They're going to say what keeps their job, keeps their family together, keeps their social situation. I made a choice that the most useful thing I can do is to be the most honest, because that's the big gap. Nobody has that. And so I quite often will disagree with the side that I'm more associated with, because I've said lots of good things about President Trump's skill set, but I have plenty of my own criticisms. He could do more on healthcare, blah blah blah. I'm trying to be as objective as possible because that was just a big void in the public discourse. Trying to be credible by not having a financial incentive, not running for office, trying to remove as much as I can from the obvious biases. I don't even vote, and the reason I don't vote is that I know that the process of just pulling that lever would bias me in a way.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:05] Also you live in California, so it really doesn't matter for you.

Scott Adams: [00:31:07] What's the point? Right!

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:08] Yeah, there's no point at all. Unless you just want to show solidarity with one side or the other. We're sort of predetermined. If you want your vote to matter, move to Michigan, Iowa, Florida, some of these other ones if you want your vote to matter. I know that's a really cynical perspective and maybe I shouldn't have that, but you know.

Scott Adams: [00:31:24] You just made me wonder. I wonder if there are just a few key battleground states where if one side can convince, you know, 200,000 people to move there within the next four years, before the next election, that could control the country?

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:37] You know, that's interesting, right? Like, "Hey, look we're building all these subdivisions." Some rich guy billionaire, "I'm building all these houses and I just don't know what I'm going to do with them. Look, I will give them to you, but you have to come to all these meetings we have about becoming a smarter, more educated citizen that just so happens to be all about all the policies that I want to foster in the country." That's actually not a bad idea and probably cheaper than all of the media that they spend trying to convince people of these same policies. This is probably a really horrible --

Scott Adams: [00:32:09] Someone's going to do this.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:32:10] Yeah, someone's going to do this. Maybe we should change the subject. I think that's really interesting. It's just not that far-fetched of an idea. You hear about this happening in regimes that are less free. For example, when I lived in Serbia, there was a lot of chatter about how Slobodan Milosevic, the dictator who's been deposed, he moved a ton of Chinese people over. They love conspiracy theories in Eastern Europe, in the Balkans especially. One of the ideas was these people came over on his behest, on his invitation, so that they could just vote for everything that he wanted, and they all live in these big blocks in one part of town. That may or may not be true, but it's kind of hard to imagine why a country like that would take in a ton of Chinese people in the '90s. It just doesn't make any sense otherwise.

Scott Adams: [00:32:59] Well, let me refer also to something from my book. There's one problem that we all have, and I certainly fall into this all the time. And the best you can do is be aware that it could happen. I call it the lack of imagination problem. If you see a set of facts and you say to yourself, "There's only one way I could explain this set of facts," it might be that the problem is your lack of imagination, because there might be several explanations; you just can't imagine them. So your example, your explanation seems quite reasonable.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:33:27] It's not my explanation, to be honest.

Scott Adams: [00:33:29] It's somebody's.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:33:30] It's the narrative from people in the street, but there could be a billion other reasons, that maybe they needed more people to work certain jobs and these Chinese people were highly trained in those areas, so they moved.

Scott Adams: [00:33:42] I tell the story in the book about how my car is perpetually dirty. And if somebody had to figure out why, they would say, "Well, you know, he seems to have the money, the free time, and nobody likes a dirty car, so maybe it's some kind of political statement. Like he doesn't want to waste water because he's in California or something like that." But no matter how many hypotheses they came up with for why my car is perpetually unwashed, they would probably never come up with the real one, because the real one is too weird. The real answer is that I have a fear of public instructions, meaning an ATM, a self-checkout, or most of our car washes have an element where you've got to do something yourself. And I'm sure that I will go into this car wash, I'll interpret some instruction just a little too literally, I'll be trapped sideways in the car wash, and they'll have to dismantle the entire building and the story will be: "Idiot cartoonist destroys car wash." And I'm thinking about all these things and, at the same time, I know that it's irrational. I can't turn it off. We're rational creatures. And so I just say, "Uh, I'll get it washed tomorrow," and then I just don't do it. So my point is, if anybody looks at this set of facts, the only thing they would never even think of is the true one. I have a weird, irrational fear of public instructions.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:34:59] That is highly unusual and a little weird. Yeah, so I thought you were going to say, "I park under a mulberry tree, and so every time I get my car washed, it's just dirty in five minutes anyway."

Scott Adams: [00:35:09] See, that would have been a far better explanation than the real one.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:35:13] Yeah, it's hard to believe. Just to be clear, because I realize how that might have sounded, when all these Chinese people moved to Serbia and I said, "It doesn't make sense otherwise," that's what I'm hearing from other people, not, "My suspicions are that this happened." It, to me, sounds like a conspiracy theory and probably is. Dictators usually don't care how people vote anyway, so the idea that you would import a bunch of people in to vote for you seems like an unnecessary move, honestly.

Scott Adams: [00:35:40] To me it just sounds like some kind of a labor reason. Cheap labor, trained labor.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:35:47] Exactly. Yeah. People who have good arguments use them. People who do not have good arguments try to win by labeling. I love this from the book because it explains so much of what's going on in public discourse. If you have no good argument, just say, "Well you're saying that because you're a racist," or "You're saying that because you're uneducated." There are a million ways to do that instead of just saying, "Here's all these reasons that you're actually wrong."

Scott Adams: [00:36:10] Yeah, the classic example is, of course, the abortion question. If your definition of life is that it starts this time versus that time, you're trying to win an argument by simply defining what the terms mean. That's not how you argue. You can't win by definitions, but people do that all the time. Now, if you look at the situation with President Trump's famous Ukrainian phone call, people on one side say he's digging for dirt. Now if that's where you start and you accept that definition of what was happening, he was digging for dirt, the conclusion is built into the definition. Digging for dirt's no good, but if you say, "Well it's a part of an investigation and it's just his job to make sure there's no foreign interference," then you come to a different conclusion, but there was no argument in between. I just sort of defined in my way versus defining the other way. Always be aware of people trying to win an argument by how they define words.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:37:04] People don't usually try to win through -- is it semantic arguments when they have facts and logic on their side? Because as you've stated, we usually like to lead with our strongest argument, and so labeling someone else or saying, "Well, define this particular word." That's usually not your strongest argument. So if you're leading with that, it's not a sure thing that you're full of it, but it's definitely not a good sign that you've got a lot more ammo in your quiver.

Scott Adams: [00:37:29] Yes. Yes, the word-thinkers are the lowest level of debaters.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:37:34] If criticism depends on applying labels instead of cause-and-effect reasoning, you're probably engaged in loserthink. I really like that. So if you're sitting around thinking of why someone's a big, mean jerk or a nasty person or a moron or racist or whatever instead of saying, "Here's where you're wrong about everything," it's a weaker argument. And I like that line of thought, because even if someone is racist, it's better to deconstruct everything that they say and show that it's wrong for a totally different reason, other than that they are a terrible person.

Scott Adams: [00:38:03] Right. Absolutely.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:38:04] It's a stronger reason, plus very few people, I should say, not nobody, but very few people are going to go, "Dang it! They're right! I'm a racist. I wasn't going to say anything, but here we are." They're going to say, "I'm not racist. It's just that here's all these things that sound really racist, but look, I have economic facts to back up my ridiculous claims that are just based mostly on my racism and rationalizing all my racist beliefs."

Scott Adams: [00:38:28] So you're reminding me of another key part of the book, which is the laundry list persuasion. I was just dealing with that this morning on Twitter. The laundry list is when somebody will say, "I believe this and this person is bad or ineffective and here are my 10 reasons." I'm sure there's an exception to this, but in my long life, when people have 10 reasons for something, that's a sign of no argument at all. Now if you say that, "Oh, you've given me 10 reasons, therefore you have no argument at all," they're going to go crazy and say, "What do you mean I have no argument at all? I have 10 reasons. I just gave them to you!" But my experience has been that if somebody has at least one good reason and it's strong, they'll lead with their one good reason. If they know that none of the reasons are strong individually, they'll put them together and try to sell them as a package. But if you say, "Well, what is your one best reason?" I was doing that this morning. "Can you pick out your best one?' And then I say, "Would you agree that if I can debunk your top, best, strongest point, that we don't really need to talk about the other nine, that you'll go back and maybe reassess your confidence of your opinion?" And so I was doing that this morning and I predict -- because this is always the pattern -- the person will resist because they won't give you the best one. Because they look at their list -- this is how I imagine, this my imagination, not theirs -- but I think they look at their list and go, "All right. I'm going to pick the best one. You know, they don't look that strong when you put it that way."

Jordan Harbinger: [00:39:55] Yeah, when they're all [seen] individually, they look a little flimsy.

Scott Adams: [00:39:59] I always remind people that 10 x 0 is still 0. So if you can't sell any one of them, it doesn't matter how many there are.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:40:07] Opinions based on experience versus projection. I like this concept because all sides typically believe they have the right facts and the other side is delusional. When I read that I went, "Crap, that's totally…" I usually think that way, too. There must be some element of human nature where we're naturally inclined to think that. I'm trying not to believe everything I think, but it's really hard because it's already in my brain. And so questioning something that my brain comes up with is not second nature at all. I then have to go, "Wait. I thought of that, but why? Well, I saw it on TV. Okay, so it wasn't my original -- it wasn't my genius that came up with this. It's, 'I heard this crap from my dad when I was 15 and I just still believe it.'" He probably read in the Wall Street Journal or, who knows? Maybe not even that. He heard it from a guy in a restaurant. So the problem here is that being right and being wrong feel exactly the same to everyone and if it didn't, everybody would just agree on everything important.

Scott Adams: [00:41:02] Right. One of the great levels of awareness you go through in your life is that, when you have an opinion and somebody else has a different one, of course you think, "Well, I'm right and that person is wrong." But you at least allow that maybe it could be the other way around. You're not going to act that way, but at least you know intellectually, "Well, they could be right and I could be wrong. I just don't feel that that's true." The one you don't think about is you're both wrong. And once you learn how subjective reality is, you start to see everybody is wrong all the time, just in different ways and about different things, and that also helps you maintain your humility. Because if I had to, you know, sort of bet on a lot of complicated debates, you said, "All right. You've got to place your bet. Is this one right, or this one right?" I think I would usually put it on both wrong. Meaning, at least both of them are leaving out some context that the other one is including, and that's what I call the half-pinion. Usually, the debate is somebody saying, "This will cost too much," and the other one saying, "Look at all these benefits." And I'm saying, "Well, those are two halves of an opinion. Maybe you would have a baby who would know that the cost of the benefits have to be compared and you should do the one, you know, follow whichever is bigger."

Jordan Harbinger: [00:42:14] So the half-pinion, I like this, too. I wrote this down. It's basically considering only the costs or only the benefits of a specific plan. So we say, "We can't do this. It's too expensive." I think that was your example. And then it's like, "Yeah, but children are our future." It's like you're not disagreeing on anything. You're just saying that education is expensive and children our future. You probably both agree on this. It's just that the one person, their half-pinion kind of, sort of, maybe -- because we don't know -- means it's too expensive, therefore shouldn't be done. But then that means that they're arguing that children aren't worth educating. I mean, you really have to fill in all these blanks with your imagination, which is not really how you get to an agreement of any kind.

Scott Adams: [00:42:56] And weirdly, it's nobody's job to do that. Like people are advocates, they're not judges for the most part. So you could tell people, "You know, you need to include the other half of the argument to be credible," and you're usually going to get, "Well, you're racist!" Nobody says, "Oh, yeah, that's a good point. I should include the costs and the benefits." People don't do that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:43:17] Yeah, the idea of being an advocate versus a judge. We could explain that a little. So as a lawyer, I'm an advocate. If I'm in court, I'm arguing for one side of it and opinion. I realize there are other arguments and they might be valid, but I'm supposed to minimize them, work around them, hopefully not ridicule them. That's the kind of the weakest form of arguing against someone's opinions. But the judge is supposed to go, "I know exactly what you're doing and I'm going to discard this and this, and these other things are emotionally valid but completely irrelevant to the argument." And then they spend six days going over what really happened in this case, and then they ask 12 people to decide on a very discrete set of facts in a criminal trial. The jury then goes, "Did this person mean to do this when they did it? You be the judge." Because the judge shouldn't even be the judge. We don't do that when we watch the news. We don't go, "Whoa. There's a lot of facts here. Let's get some from multiple sources, run it through the gamut of logical argument, you argue for thus side, you argue for that side, and then 12 people who are supposed to be impartial should then sit around for the next three days and think about whether or not that's correct." We just go, "Sounds right."

Scott Adams: [00:44:23] Just the fact that the legal system exists, and I would say is sensationally successful. Lots of mistakes and imperfections, but the American legal system is like the eighth wonder of the world. I mean, it's just amazing. It's what makes this country the powerhouse it is, I think. But look what it takes to get it almost right. Like you said, you need the judge, the jury, the advocates. I mean, it takes a lot to take the subjectivity out of this stuff, and in our daily lives we don't do anything like that.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:44:55] No, and it's because it's inefficient. We're not evolved to go, "Well, I need a six-day deliberation on whether or not this mattress commercial is really telling me the truth." It's just not going to happen. You know, like "Wow, this phone looks really cool. I want it because it'll make me cool among my friends. Let me think of all the reasons why I now need it," not like, "Let me bring this out to my board of directors among my friends and figure out whether I need this." Dialing down the ego is a really good exercise here. It reduces this unwarranted certainty that we all have in our own opinions. The practical that we can include in the worksheet here is journaling when we are certain about a political outcome or a prediction. You kind of mentioned this earlier in the show. Journal out these predictions and then note when we're wrong.

Scott Adams: [00:45:39] Yeah, you don't have to write them down. You can just tell your friends, because your friends will remind you when you're wrong. It's coming back. I say take your personal predictions and put them into the world. Put them on Twitter, write them down and tell a friend, and really note when you're wrong, because that's what gives you at least the ability to say, "Okay, maybe I'm not right all the time." This idea of dialing your ego up and down, it has to do with treating your ego like a tool as opposed to who you are. I think most people go through life thinking that their ego is sort of a core part of who they are and they're trying to protect it. "Don't let me get hurt." So your ego is just protecting you from embarrassment, protecting you from pain, protecting you from discomfort. It's more productive to see your ego as your enemy and something you should turn into a tool, not an identity. What I mean by that is there are times when dialing your ego up is the best thing you could do. Let's say before going into a sport competition, before taking a test, before doing a job interview. You don't want to have too much ego -- that can be wrong, too. But there's plenty of science that shows that if you can build your confidence up to a certain level, you'll just perform better. It's good to be able to crank it up when you can before I go into anything important. I might actually play a little loop in my head that says, "I'm good at this. This will be great. Everybody will like this." Even if it's not true, you're just dialing your ego up for effect. But you don't want to keep it there. You want to be able to dial it down just as easily when you're in some complicated conversation. You think, "Well, I think I know the right thing to do here, but I could be wrong." And so I keep that loop playing when I'm in a debate with somebody who's disagreeing with me. Just continuously, I'm saying, "But this time, the problem might be on my end." I'm looking for that. I'm trying to find where the problem is on my end, and that gives you at least a little bit of protection against your ego making claims that are ridiculous just to protect your argument.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:47:36] Yeah, and I find this even just as a full-grown ass man, I often have to go, "Am I holding on to this because I want to be right?" Well, I'm married, so of course, this happens to me all the time. "Am I holding on to this because I want to be right, or is this person actually saying something that I should listen to, but maybe they're delivering it in a way that isn't great. Or maybe this is just a touchy subject for me and so I don't want to admit that I was wrong." This is in my email inbox every day, because the show fans are really vocal and they'll go, "You know, you said this and I disagree with you. And I love the show, but this I really disagree and here's why," and I have no problem with that. But it's that exact same point where made and someone goes, "I thought you were smarter than that. Clearly, you're just another moron who believes XYZ." I'm going to go -- I'm going to dig in my heels, but they might be equally right. They might be equally correct on that point. I just threw my pen across the room. That's how strongly I feel about this.

[00:48:34] Choosing ego over effectiveness is classic loserthink. Is that your button on the end of the chapter there?

Scott Adams: [00:48:00] Yeah. I mean I had a job opportunity once back in my corporate days where a high executive of the bank offered me the job to be his personal gopher. So I would just run around and do little projects and stuff. It was kind of a low-end job and it would have been less prestigious than the job I already had, which was managing a small group. I didn't want to go from being a manager to a gopher. But he said, "You know, you realize this will give you exposure and you'll meet the right people," and I said, "Yeah, I like my job where it is, not this gopher job." So I turned it down. He was the senior vice president of the bank. He called me and he said, "You're a fucking idiot," and I was like, "I'm glad I turned that down. I don't want to work for this guy." My buddy takes the job, and very soon he was one of the youngest senior vice presidents of the bank. Because I was a fucking idiot because I took my ego and I said, "No, I'm not going to take a step down. I don't want to take a step down." I think the pay wasn't any different, but it was an ego step down. But the guy who took the ego step down knew that it was a step to get to the place he wanted to be. He met the right people. He impressed them. He was a senior vice president. The youngest one the bank ever produced.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:49:52] Wow. Yeah because he networked, met with everyone, got in the room and all their meetings or whatever. Sure, he was the note taker, but that's how you get in the room.

Scott Adams: [00:50:00] Yeah, so your ego can just kill you if you're letting it make your decisions.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:50:06] You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Scott Adams. We'll be right back after this.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:11] This episode is sponsored in part by HostGator.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:50:14] It's 11 o'clock. Do you know where your website is? Looks like there's another outage at your target audiences' primetime. Costing you precious dollars every minute when it's down. It's a grim scenario that's played out daily across the globe to the frustration of small business owners like yourself and your customers. With web hosts as plentiful as the stars in the sky offering the park that prized domain within your modest budget, it's no surprise you're going to pick a few duds along the way. If you've entrusted it to anyone who's not been in the business of providing secure, efficient, simple and affordable web hosting services since 2002, it's anybody's guess as to why your site's down again. But if your website is handled by HostGator one of the oldest and most trusted services on the Internet, it's up and running just like it should be. HostGator's 99.9% uptime guarantee and around-the-clock support ensure your website is available to the eyes of the world every day and night of the year. Got a tight budget. No worries. As long as you're a new user you get to try any HostGator package for up to 62% off the normal price, just for hearing the sound of my voice. And if you're not completely satisfied with everything HostGator has to offer, you've got 45 days to cancel for a refund of every last penny. Check out hostgator.com/jordan right now to sign up. That's hostgator.com/jordan.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:51:27] This episode is also sponsored by Ancestry. This is such a fascinating product. You all have heard of these DNA testing and everything like that. There are some people who are really into it. There are some people who really aren't but I think it's so fascinating to find the DNA aspects of health, disease, longevity, of course, your family history is in there. It's just that part to me is fascinating. Where did we come from? I'm 0.4% Yakut, which is like these Central Asian people, aka that's my Genghis Khan streak and the DNA there. They've got a free trial so you can learn about your family history as well. It's a cool gift for the holiday season. You can connect families all over the holidays. Every family has a story and you can find your ethnic origin in there and it can bring you closer to that. It can also help you find new relatives. Should you want to do that? So it doesn't just tell you the countries are from but it can pinpoint specific regions within them. I guess people have less mobility back in the day, so you can get some insightful geographic detail about your history and recent ancestors, especially if you've moved from place to place around the world from discovering your origins to over 500 regions and you can connect to other living relatives. No other DNA test delivers such a unique interactive experience. There's a hundred million family trees. Wow, that is a lot and billions of records to get insight into your genealogy and your origin sign. Man, this is really a cool experience to have. So if you're curious about your family history. Jason, tell them where they can get a deal on Ancestry on their own ancestry.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:52:54] Save big on Ancestry DNA was special holiday pricing and spark meaningful conversations around the holiday dinner. Give the gift that can unwrap their history. Head to our URL at ancestry.com/jordan to get your Ancestry DNA kit on sale today. That's ancestry.com/jordan.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:53:13] This episode is also sponsored in part by Pattern Brands. We're constantly challenged to find a daily balance in our lives due to the demands of work in the need to feel constantly productive, which is kind of my middle name here, the need to feel not actually being constantly productive, just the need to feel that way. You can always be present in the kitchen and man, cooking, I know Jason this is like your thing to get away from it all, so to say.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:53:35] Yeah, totally, I've tried to get you into it for years.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:53:38] No, thanks.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:53:39] But you don't like to relax. So there's your problem right there. But yeah, the kitchen is where the heart is.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:53:45] Yes. No, I don't like to relax. In fact, even my downtime is things that are not relaxing like Call of Duty or something right? Like anything that gets your heart rate up when I'm trying to get away from all the stress. So Equal Parts has great recipes to make home cooking a fulfilling and rewarding experience. They've got great cookware built from high-quality environmentally-responsible material. So it's not a bunch of like plasticky schmutz in there. This is the cool part, you get coaching from real chefs, who are standing by seven days a week to provide one-on-one expertise and insight into every step. You can literally text them and chat with them and ask them questions about tweaking the recipe, getting the recipe together. You can put on a little music, put your screen down for a bit, allow yourself some time to create and then you can serve the meal to friends and family. It's really simple to be focused, be mindful while feeling productive and learn a little bit of that cooking stuff. I think that it's rad that you can tell them what's in your fridge and they will help you craft a meal based on that. So you can be like I got leftover Stromboli, some ketchup, some hot sauce, and a potato, and they're like, "All right, we got you covered."

Jason DeFillippo: [00:54:52] It's like MacGyver for the kitchen. It's awesome.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:54:55] That's right. It's like MacGyver for the kitchen. I love that. Get into the rhythm of the kitchen with a little get your MacGyver on man. Jason.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:55:02] Get into the rhythm of the kitchen with friendly and inviting-cookware coaching and guidance from Equal Parts all with free shipping and free returns visit equalparts.com and get 15% off any purchase with code Jordan. That's equalparts.com enter code Jordan, and take advantage of that coaching when you're starting off in the kitchen, that is the best thing to have. Someone that you can call up and just say, "Hey, what is a shallot? And what does it do?" That's equal parts.com enter code Jordan.

[00:55:28] Thank you for listening and supporting the show. Your support of our advertisers keeps us on the air and to learn more and get links to all the great discounts you just heard so you can check out those amazing sponsors, visit jordanharbinger.com/deals. Don't forget the worksheet for today's episode. That link is in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast. If you're listening to us in the Overcast player, please click that little star next to the episode. We really appreciate it. And now for the conclusion of our episode with Scott Adams.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:55:58] People have problems comparing things. That's something I really took away from this book. And I love this because I never really wrapped my mind around this, but people will say, "Oh, man. Did you see that Family Guy episode where they made fun of this and this and this?" And it's very persuasive because it's hilarious and they've got songs, and it's well done and Seth MacFarlane is like a genius in all these different areas. But again, we don't necessarily have a common language when we're comparing things. Like look, we'll put Seth MacFarlane aside, but somebody on Twitter might say -- or on the Internet or on a show like this -- might make a really persuasive-sounding argument, and I might try to counter that. But if we're talking about something that neither of us have formal training in, we don't have a common language. We don't realize that comparing things is actually a learned skill. You can't just weigh them in your mind and sort of generally rationalize why one is better than the other. Your brain's just picking the option it prefers and then figuring out all these reasons based on what you already have in the tank. It's not using the right measuring stick for the job, necessarily.

Scott Adams: [00:56:59] I mentioned I'm a trained hypnotist. One of the things you learn is that the basic nature of humans is that you make decisions and then you rationalize them after the facts -- at least for important stuff that has some emotional content. We're rational enough on little stuff like figuring out how to use the remote control, but on the big stuff, we think backwards. We make decisions based on how it feels, then we explain why we did it later and that's just a ridiculous explanation, usually.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:57:25] I'd love to hear your strategy on how to spot fake news. There's kind of a how-to in the book on what you should be looking for to decide whether something is fake or not.

Scott Adams: [00:57:33] One of the best, I guess the best advice I ever heard, was from Scott Alexander, and that's a pen name -- a blogger. We don't know his real name. But he pointed out that often when you hear a story that is too amazing to be true, it's because it's not true, and later you're going to find it out. And not only is that dynamic fairly common, but it's almost universal. Meaning that if you see something that your first reaction is, "My hair's on fire. I can't believe somebody did something so crazy and amazing." 48 hours later, you can find out it didn't happen at all. Now if you use that "This sounds too ridiculous to be true," if you use that as your standard, you're going to be right about 80% of the time. But if you say "Hey, it's in the news. This is the news source I watch. I always watch this news source," whether it's the left or the right news, and you say, "Well, they're reporting it like it's a fact; it's probably true," you're going to be wrong about 80% of the time and specifically on -- I'm just talking about the stories where as soon as you hear it you go, "Ah, that can't be true." Probably, it isn't. So that's technique number one.

[00:58:44] The other thing is make sure that both the left and the right press are reporting it the same, because if they are, it's probably a fact. If only one of them is -- and it doesn't matter which one, that's the other thing -- then it probably is not. You'll probably learn later that it's not a fact. So those are the big ones. And if you keep those rules in mind and wait 48 hours, of course -- don't make a quick decision. You'll be in good shape.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:59:08] Also, you've got the 20-year rule, and I thought this was kind of interesting. I wanted to know what this is, and of course, how this benefits all of us and not just politicians or celebrities or people going into the Supreme Court, for example.

Scott Adams: [00:59:18] The 20-year rule I just made up.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:59:22] I mean, it's your book, so a lot of it's just made up!

Scott Adams: [00:59:25] But other than that, where do manners come from? Somebody makes them up. There's some point where somebody says, "You know, I watch people act and when they act this way, I kind of like it. It works better for society. I guess this is a rule now." So I'm making up a new one, because the environment has changed and we need a new rule. And what happened was social media and our ability to find somebody's mistakes on film were recorded from 20 years ago, just didn't exist before, at least not any kind of common way. So we now have the tools to hate somebody for something they did decades ago when they were literally a different person, because you're not the same as you were 20 years ago.

Jordan Harbinger: [01:00:06] No, I'm for sure not.

Scott Adams: [01:00:08] I'm not the same as I was at 19. You didn't want to know me when I was 19. Trust me. I was not a good person. Now, most people improve throughout most of their life. If you have what I would call the ideal life arc, you start as a selfish little baby who can't do anything but take. You get to the point where you can help society, maybe your parents, you're raising a kid, you're paying your taxes, but you're also taking a little. And then maybe you get to the point where you've taken all you need. You've made your money and you're at the end of your life. You're in full give-back mode. Like that would be the perfect situation.

[01:00:45] What was I talking about? What was your question?

Jordan Harbinger: [01:00:47] We're talking about the 20-year rule.

Scott Adams: [01:00:49] Oh, the 20-year rule.

Jordan Harbinger: [01:00:50] I got distracted because you said you wouldn't want to know me when I was 19 and I was like, "Scott Adams is 39? What the hell?" I realize you're probably talking more about me 20 years ago than you 20 years ago.

Scott Adams: [01:01:00] Well, all of us. So the point is that we were not the same people we were 20 years ago. And so I have somewhat arbitrarily picked 20 years and said, "I don't care what I find out about you or anybody else. If it was 20 years ago, it doesn't count." Now you have to throw in some exceptions, like pedophilia or something, but we're not really dealing with that for most situations. If I see, for example, some governor who wore blackface 30 years ago, certainly I don't endorse it or approve of it, but I also don't count it. Is that person the same person they were? Would they wear that today? Probably not. I'd rather judge people by what they've done recently and I do apply this to the left, the right, my enemies, my friends. It's a rule I try to be pretty consistent with. And you never needed this rule before. Because everything I did in high school that was a dumbass thing, there's no record. Worst-case scenario is there's an uncredible witness who says something. Then I say, "Well, they're a liar."

Jordan Harbinger: [01:02:01] Or, "We were all drunk at the time, but we're all pretty sure he did this thing that was really horrible." "Where were you?" "I don't remember that, either. I just remember this general thing." I worry about that now because having a son who's three months old, I'm like, your whole life can be every dumb thing you do -- you might even record it yourself, and then what?

Scott Adams: [01:02:21] My late stepson lost his first job because he was on the job for a week and somebody produced a Snapchat video where he was in the wrong place and that was it. Fired! For something that he didn't even do. Somebody else filmed it and put it on social media and it wasn't that bad. I don't need to get into details, but the employer didn't want to be associated with it.

Jordan Harbinger: [01:02:44] Jeez, yeah, it's scary. Because now your actions can be policed. Look, if your actions can be policed in real time, that's scary enough. The fact that somebody might police something you did, taking it out of context and then putting it in the 20 years from now context, is pretty bad. I mean there were things that I did 10 years ago and even five years ago where I go, "That was like, kind of tasteless. It was a little gauche given the climate we're in now, and I should be accountable for that if it hurts someone. But if it didn't hurt someone and it was 20 years ago, and now I'm trying to get a job and I can't, that really sucks. It's bad for society, because your sort of imputing the intention that somebody had 20 years ago, in a totally different scenario and context, into what they're doing now -- and with few exceptions, namely like certain violent crime, maybe pedophilia, whatever example you want to go for. If someone murdered their neighbor 20 years ago, yeah, maybe I don't really want them working in my company. But if somebody got too drunk at a party 20 years ago and said something obnoxious, I would like to think that maybe we could forgive that person by now at this point.

Scott Adams: [01:03:51] I would say forgiveness is a great thing and I'm a big fan of it, but that's not even necessary. Because if somebody did something 20 years ago, that person doesn't exist anymore. They literally don't exist. So the new person is -- whatever they're doing, you can judge them by. I prefer judging people by how they respond to their mistakes than by their mistakes. But yeah, that old person doesn't exist. Let's ignore them.

Jordan Harbinger: [01:04:14] You've got this concept called the magic question, and this was great because I can see this solving a lot of arguments that probably never even needed to happen in the first place.