What hurdles must humanity face before it can inhabit the final frontier? A City on Mars co-author Zach Weinersmith is here to ground us with the facts.

What We Discuss with Zach Weinersmith:

- How tethered to reality are Elon Musk’s grand plans for the human colonization of Mars? Shouldn’t we focus on ensuring the sustainability of our current world before investing in centuries-long efforts to squeeze life out of a dead planet?

- With current technology, how well can human bodies be protected against prolonged exposure to radiation, extreme temperature fluctuation, and lesser gravity on the Red Planet and the Lunar surface?

- The economics of farming, mining, and extracting resources in space.

- The political, legal, and ethical considerations of space colonization.

- If now’s not the most prudent time to hurl our species into the cold, uncaring void, then when?

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

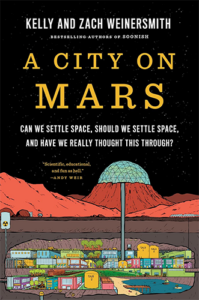

But wait! Not so fast. On this episode, we’re joined by Zach Weinersmith, co-author (with Kelly Weinersmith) of A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? Here, we discuss the hard-science complexities of space exploration and colonization that tend to get glossed over by the media, the political and ethical considerations of exporting human interests out of this world, the economics of extracting resources in space, and, if the time isn’t now to expand our reach into the extraterrestrial, then when? Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. We appreciate your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini-course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

Subscribe to our once-a-week Wee Bit Wiser newsletter today and start filling your Wednesdays with wisdom!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- US Bank: Apply for the US Bank Cash Plus Visa Signature Card at usbank.com/cashpluscard

- Shopify: Go to shopify.com/jordan for a free trial and enjoy three months of Shopify for $1/month on select plans

- SimpliSafe: Learn more at simplisafe.com/jordan

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- Court Junkie: Listen here or wherever you find fine podcasts!

Miss our conversation with science champion and astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson? Make sure to catch up with episode 327: Neil deGrasse Tyson | Astrophysics for People in a Hurry!

Thanks, Zach Weinersmith!

If you enjoyed this session with Zach Weinersmith, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith | Amazon

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal

- Zach Weinersmith | Website

- Zach Weinersmith | Patreon

- Zach Weinersmith | Mastodon

- Space Colonization Won’t Look Anything Like the Frontier | Foreign Policy

- Five Hazards of Human Spaceflight | NASA

- Why Space Radiation Matters | NASA

- Astronauts’ Brains Change Shape during Spaceflight | University of Michigan News

- Joining the 245-Mile-High Club Would Be ‘Quite a Challenge’ Warns Scientist | Newsweek

- Real Martians: How to Protect Astronauts from Space Radiation on Mars | NASA

- What Does Spending More than a Year in Space Do to the Human Body? | BBC News

- The Challenges of Landing Humans on Mars | How the Universe Works

- Growing Food in Space: The Final Frontier | AgLab

- What’s the Minimum Viable Population of a Space Colony? | Planet Pailly

- The Fault in Our Mars Settlement Plans | The Space Review

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies | United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs

- Humans Will Never Colonize Mars | Gizmodo

944: Zach Weinersmith | Out-of-This-World Hurdles to Colonizing Mars

This transcript is yet untouched by human hands. Please proceed with caution as we sort through what the robots have given us. We appreciate your patience!

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Special thanks to US Bank for sponsoring this episode of the Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:04] Coming up next on the Jordan Harbinger show.

[00:00:07] Zach Weinersmith: What's called microgravity? Just you can think of it as no gravity reliably that does all sorts of bad things to your body. Notably, you lose something like 1% of bone density in your hips per month. You also lose muscle strength very quickly. You reliably lose vision in space. This is one of the lesser known things about space, is that people are actually sent up with glasses to adjust to the expected vision loss, and that doesn't come back. There's just a thing that happens in space.

[00:00:36] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On the Jordan Harbinger show. We decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people and turn their wisdom into practical advice that you can use to impact your own life and those around you. Our mission is to help you become a better informed, more critical thinker through long form conversations with a variety of amazing folks, from spies to CEOs, athletes, authors, thinkers, performers, even the occasional arms dealer, drug trafficker, four star general or Hollywood filmmaker.

[00:01:03] And if you're new to the show or you wanna tell your friends about the show, I suggest our episode starter packs. These are collections of our favorite episodes on persuasion and negotiation, psychology, geopolitics, disinformation, cyber warfare, China, North Korea, crime and cults, and more to help new list.

[00:01:17] Listeners get a taste of everything we do here on the show. Just visit Jordan harbinger.com/start or search for us in your Spotify app to get started today on the show, my friend Zach Wiener Smith on growing up being bullied because of your last name. No, I'm, I'm kidding. Sorry, Zach. Today we're actually gonna be talking about colonizing space.

[00:01:33] Is it possible to colonize the moon? What about Mars? What problems will humans face living off of the earth? How do we create a biosphere, for example, you know, a place where people can live without dying immediately. How do we generate power? How do we get enough food? How do you raise a family? What type of government will we have?

[00:01:50] What about like asteroids and space junk radiation? There's so much to think about when making these bold leaps or as they are right now, bold statements about how humanity may one day expand outwards from the earth and beyond. So we're doing a deep dive today into the details of what that might look like here on the show with Zach Weiner Smith.

[00:02:10] Here we go.

[00:02:14] Zach, thanks for doing the show. This topic is quite interesting and it's, it's all the rage, right? You get Elon saying, we're gonna colonize Mars. He's like, I'm gonna die on Mars. Still time for that, I suppose, but probably not in the way that he thinks. In a thriving metropolis of a city on Mars. I would say this is a terrible way to begin an interview, but I'm Your last name is Wiener Smith, which?

[00:02:36] It's Wiener. Wiener. Wiener. Oh, it's not even like, okay. 'cause if you look at the German, it would be Weiner Smith. That would be nice. Right? If that would be nice. That was kind of where I was going with this. I'm just thinking like, man, first grade bullies seldom split that hair between, well that's actually, if you go by the German, it's Weiner Smith, so we shouldn't shove him in a locker

[00:02:55] Zach Weinersmith: right now.

[00:02:56] Well, no. So my, my maiden name is Wiener. Kelly's last name was Smith. And we, we thought this was funny. And my, my 9-year-old is just realizing that it's funny, it's still funny for her now. Right? What happens in three years is gonna be interesting.

[00:03:09] Jordan Harbinger: Okay. Because I was thinking it doesn't even make sense, right?

[00:03:12] Because VNA just means somebody who's from Vita, essentially. Right? But then Smith is what it sounds like, like a blacksmith or somebody smiths something. So I'm like, who's smithing people from Vienna? It doesn't sound like a real, but then I looked at my own name and I was like, there's no sense to any of this crap anymore Anyway.

[00:03:30] Zach Weinersmith: You're, you're not a harbinger of anything.

[00:03:31] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Like, I mean maybe, but also like you really have to stretch the definition out in order to make the shoe fit. So. I don't know. I just remember reading this and I was like, of course these guys are space geeks because you know how far away from these boys can I

[00:03:47] Zach Weinersmith: get Mars?

[00:03:47] Sounds good. That's right. That's no. The old joke is, the reason astronauts all come from Ohio is they're trying to get as far away as possible from

[00:03:55] Jordan Harbinger: Ohio. That actually makes a lot of sense as a guy from Michigan. I get it, Uhhuh. Alright, let's talk about colonizing mars slash space in the first place.

[00:04:04] 'cause again, it's an exciting prospect. I know you're gonna rain on our parade, which is fine. I think a reality check every now and then is probably a good idea. Especially because look, no shade on Elon. The dude's done some amazing stuff from SpaceX to Tesla and I was a early-ish investor in Tesla and that turned out really great.

[00:04:25] And so look, no shade on the guy. He is done some amazing stuff. But there's also stuff where it's like, I paid for a self-driving car and I'll be damned. I drove that thing myself. The last, well, forever. I've never had it drive me anywhere. Some of that is 'cause I'm scared and some of it is because it doesn't work that well.

[00:04:41] Right? And the Mars thing seems like another, Hey, we're gonna do this, it's gonna be within 50 years and then in 200 years we're gonna be like, so we thought it was gonna be 50 years, but now we're saying within 30 years we're definitely gonna start doing that. And it's gonna be like, wait a minute, this is my great-grandfather wrote about this as a thing that almost seemed like it was happening now.

[00:05:02] And we're just building launch vehicles. That's kind of how this looks to me now after reading your book especially.

[00:05:08] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah. Yeah. So, uh, let me, let me give you the positive case before I come in with the bummer. Sure. The positive case would be essentially that the launch technology really has been revolutionized.

[00:05:19] There are some people who, because Elon Musk is kind of a jerk, especially when he gets on his personal social media network. Yeah. Want to make it out that he's just a grifter all the way down. But SpaceX has been genuinely revolutionary new technology. It is an idea that's been around since the early days of space, which is reusable rockets, and they actually got it done.

[00:05:37] Before, like every space agency in the world. Mm-Hmm. And they actually dropped the prices. You can actually look at the prices of like space launch going back to the forties. They dropped drastically in the early space age and then they just absolutely hit a plateau. They arguably get even more expensive.

[00:05:52] So like, you know how everyone was miserable about space from like 1980 to 2015. Mm-Hmm. All the dreams died. That's why the price stayed high, but it started collapsing. And that's mostly down to SpaceX. So that's like, that's the case for optimism. I really are gonna be able to do a lot more in space. So

[00:06:07] Jordan Harbinger: it is getting cheaper and cheaper to launch things into space.

[00:06:10] That's great. And I know there was that plateau for a while. I. Can you give us an idea of how the cost of putting things into space has dropped over the years? Maybe you can choose like a household item, you know, to mail or mail to send this mug to space would've been like 10 grand in in 1968 and now it's like $4.

[00:06:27] I don't know. Why does that

[00:06:28] Zach Weinersmith: look, that's actually not too far off. The number we used to always give like 10 years ago was $10,000 a pound, which like, one way to say it would be an Apple seed would cost about $10 to send a space. Wow. Right. So it's zany expensive under SpaceX. I mean, you know, without getting into the weeds, 'cause it can be very hard to make comparisons between depending on what you're doing.

[00:06:45] But like now it's more like a thousand to 3000 per pound. Something in that range, depending on what you're doing. Right, okay. So it's like genuinely a change, right?

[00:06:54] Jordan Harbinger: It's dropped 70 to 90%. Yeah. That's really amazing. But it seems like we need it to get to 99.9% cheaper before it's like yeah, let's send a skyscraper up with a rockets attached to it or whatever the plan

[00:07:08] Zach Weinersmith: is.

[00:07:08] Yeah, I think that's probably right. You need it to keep getting cheaper. But I will say, you know, it's worth noting the cheapness opens up other stuff. So if you look at the James Webb telescope, part of why those things are so expensive is they have to be crammed. Every last bit of mass is precious in these fairings.

[00:07:23] Mm-Hmm. So you get to a world where you have much bigger ships that are much cheaper, you can do a lot more off the shelf stuff. You can like waste more space. I see. Yeah. So, so there is the whole economy, I'm trying, this is the optimistic side of this. This is why people are really geeked out, is because there genuinely is a change happening.

[00:07:37] Jordan Harbinger: This makes sense though. So for, 'cause that almost went over my head, so I'm gonna assume that some people maybe didn't pick up on that. So right now you've gotta pack this massive satellite, a delivery vehicle and all the tech and all the solar panels that unfurl and whatever into the smallest possible package.

[00:07:54] That's the lightest possible to launch it. So you're using all these well space, age materials, super expensive stuff. Hey, we need a custom X, Y, Z widget that fits into this tiny little space and this weird thing. 'cause this is all we have left. And they're like, great, we'll make it for $10 million. But once it gets cheap enough, it's like.

[00:08:11] No, we're just gonna buy a bunch of like space proof Apple Mac Studio computers and shove them in a rack and then launch those. And that's like, oh, that's a million dollars instead of a million dollars for the piece that holds the thing

[00:08:24] Zach Weinersmith: together. Yeah, exactly. And in addition, you know, you take starlink for example, you could estimate roughly speaking of this new giant rocket SpaceX is working on called Starship Works.

[00:08:33] You could launch something like say three or 400 mini setss per launch. So you're now also getting economies of scale. Mm-Hmm. So it really is, I don't wanna take anything away from this aspect of it. This is like amazing stuff that's happening that is really

[00:08:45] Jordan Harbinger: world changing. Yeah. That part, I wanna keep it optimistic, right?

[00:08:48] Because even though we're gonna poke holes in the, the balloon slash ran on the parade, whatever metaphor we wanna use, I don't want people to be like, oh, we're never going to spa because never's a long time. Right. And it's frankly, almost one thing that I will say Elon and all the other pro space folks have done is if you'd asked me like.

[00:09:07] 20 years ago, if we were ever gonna colonize space, I would be like, absolutely not. Definitely nothing in my lifetime. And I don't mean a city on Mars, I mean like anybody. I'd be like, no, it's just science fiction. Now I'm thinking, okay, we just, maybe a pause in global hostilities would be great and some resource dedication to this, but it's not impossible.

[00:09:28] There's just ways to do this that didn't exist and certainly were not in my mind a couple of decades ago. And that that's more important I think, than people realize, is once you get people to believe that something is possible in large numbers, people who are talented start going into those fields when their kids and they start studying this stuff, and then you get this critical mass of people that are like, we could do this.

[00:09:48] And that's how stuff like this gets done, period. I would imagine. Yeah, a

[00:09:52] Zach Weinersmith: hundred percent. I mean, I really think, you know, part of why space settlement is a thing that's talked about a lot is it's very inspiring and it helps to get a lot of young, talented engineers to want to come to work at a place like SpaceX, even though they're like work hours are notoriously brutal and difficult.

[00:10:08] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Ev a couple of ex SpaceX friends and they're like, you don't understand, like, I work at Apple now. It's way more chill. And if you know anybody who works at Apple, they're like, what are you talking about? Apple is not chill at all, but SpaceX is something else. So if the bottleneck isn't cost. What is it?

[00:10:23] It's something else. What is it?

[00:10:25] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah, I would say it's a variety of things, so I'll give you an example of one that to us is very important, which is we know almost nothing about whether humans can reproduce in space. We actually, strictly speaking, don't even know if humans can mate in space, though I'd, I'd say it's almost certainly yes.

[00:10:41] But conception development, everything you have to do to have a civilization, right? Not just like an outpost, like an antarctic base type of thing. Okay. We don't know how to do that. The science, like there, there's a tiny amount of science that's been done on space stations. It's totally unsystematic. It's like we have one thing with six rats over here and a thing done on quail legs over here.

[00:11:00] And some, uh, you know, livestock sperm was sent to space over there. But we don't have a kind of like program to answer this

[00:11:06] Jordan Harbinger: question, right? I'm imagining recruiting a space program. And they're like, what are we gonna be doing? And they're like, you guys are gonna be banging a lot. And filming it and filming it and sending it to all of us for analysis.

[00:11:18] It's like, I don't know how many people are signing up for that. You know, I

[00:11:20] Zach Weinersmith: was never able to track it down. But there's a persistent story. Which is probably not true, but in the waning days of the last Soviet Space Station, when they sort of lurched into hyper capitalism, there was a proposal to shoot a pornographic film on, on space station mirror.

[00:11:34] Oh man. But I don't, there, there are legends that crop up all over the place with this stuff. There's a persistent legend that someone somewhere has had sex in space. We disagree about this. Kelly thinks it's probably happened. I think it probably hasn't, but it's, you know, one of those questions for the ages, I guess.

[00:11:49] But is the whole

[00:11:50] Jordan Harbinger: thing is that it's not like there's gotta be almost no area of that whole thing that's not That's right. Monitored. So if they're watching you do all this other stuff, I guess if you can really get over the fact that somebody's watching you live at 24 7, I don't know. It seems a little unlikely, but, but who do I, what do I know?

[00:12:05] What do I know? All right, let me back up a little bit. Yeah. I know one of the bottlenecks is creating a biosphere. Yes. Tell me, well, first of all, what is a biosphere and what is the problem here? Because we've made biospheres on earth. Right. The biosphere too. I remember that. I remember the crappy poly shore movie.

[00:12:21] Yeah. Of the same name. But why is this so difficult? What are we missing from that? Yeah,

[00:12:26] Zach Weinersmith: yeah. So to explain what it is and why you would want it. So a biosphere also called a closed loop ecology. But the basic idea is you have a sort of sealed bubble and inside it you put plant, animal, bacterial life. And it's just self-sustaining.

[00:12:40] It doesn't turn into like goo, right? It doesn't die off, doesn't get out of control in some way. It just exists and does all the stuff that Earth does for you, right? You generate oxygen, the plants absorb carbon dioxide and you have these loops, these ecological loops. The reason you want that in space is 'cause space is awful everywhere.

[00:12:57] Without exception, the moon is just terrible. There's obviously no air, but also like the ground is trying to kill you. Mm-Hmm. The soil can't make plants. Mars is similar. It has other problems. And so really what we are talking about when we're talking about putting a city on Mars, any kind of habitat on Mars is that you have to have one of these ecologies inside it, like a self-contained fake ecosystem that is not directly interacting with the outside world.

[00:13:20] Mm-Hmm. Right. Except in the sense of maybe absorbing like mass in that dirt from Mars. Could say with a lot of work, be ameliorated to be brought into the system, but mostly you're trying to not have a strong interaction other than to get sunlight. Can we do this? It's been a question that's been around since the sixties.

[00:13:36] The Soviets did some work on it that was kind of inconclusive. And then there's been a few experiments here and there, and the biggest one by far is the one you mentioned called Biosphere two. And by the way, there was no Biosphere one Biosphere one is Earth. They were being a little cheeky about it. Oh, I

[00:13:52] Jordan Harbinger: wondered about that.

[00:13:53] I'm like, we never hear about the first one. It must have just been a short-lived project. Whoops. Okay. That explains it. Okay. Yeah, that's fine. They,

[00:13:59] Zach Weinersmith: they did have prototypes, but so it was run by this kind of crazy guy. He's still alive, I think his name John Allen. It's kind of like a, A Steve Jobs before you could be Steve Jobs, like a guy who talks in tech, speak about kind of crazy stuff, but also does big projects.

[00:14:11] And so hence like the kind of artsy quality to the project. But essentially what it was is you had the facility that was about the size of three football fields and it was sealed. And eight humans went in and they survived for two years. In that sense, it was quite successful. The downside is, at one point they were suffocating, the system was absorbing oxygen out, and they didn't know that they couldn't figure out where the oxygen was going.

[00:14:35] It's a really weird thing to have in a sealed system for oxygen to just to disappear. Yeah. Yeah. It just turns out the structure was absorbing it like chemically. Wow. Also, they were like starving. They lost I think 10 to 18% of body weight and they weren't like. Chubby people. You can look at pictures like they're just running outta food.

[00:14:50] They weren't making it fast enough. And there, there were other problems I'd get into. They also were fighting, by the way, they didn't speak for like a year. There were two factions of Ford that hated each other. Oh my God. Yeah. There's a story at one point that got so bad. Two people from one side came and spit on a woman.

[00:15:03] I think it was two people at separate times the same day. It was like a coordinated strike,

[00:15:06] Jordan Harbinger: coordinated spitting. This is like a Seinfeld episode or something. Only totally. Scientists, you should know better, but I guess if you're starving and possibly suffocating and you've been with the same people for two years and you weren't sure how, yeah, I can, I'm not a guy you wanna put in a biosphere, let me put it that way.

[00:15:21] Yeah, definitely not a hundred

[00:15:22] Zach Weinersmith: percent. I wouldn't wanna do it either. You can only say it was a qualified success and it, you know, there could have been more going on. They only did one other run that got called off short because there was like financial mismanagement in fighting. Fun fact, by the way, the one of the guys who helped get it back or take over and finish the project off was Steve Bannon, uh, is like an early wait.

[00:15:41] Jordan Harbinger: The Steve Bannon that we're currently seeing the that guy. That one. Yeah. Okay.

[00:15:46] Zach Weinersmith: That's there, there is no more to that Fun fact. It's just one of the weirdest little Steve Bannon suddenly pops into my space science story, uh, and then leaves the scene.

[00:15:54] Jordan Harbinger: You like this has to be a different Steve Bannon. Right?

[00:15:56] Let's go over that. I did look, I did check. Yeah, I'm sure you did because otherwise you're like, wait a minute. I mean, I'm still mentally double taking from that. That seems so off brand. Well, okay.

[00:16:05] Zach Weinersmith: But it was, it was in, in the context of being part of a financial firm. Okay. So it's, uh, yeah, I see. Yeah, shees.

[00:16:10] Alright. But anyway, so that basically called off. We have some data from it. The people who worked on it still work on some of this stuff, but since then there's just been small scale experiments like in Europe and Japan and China. That's it. So the max scale we have is eight people. Right. So if you're talking about a million people on Mars who need to be supplied by a system like this, if it scales, if it's like the same size, right?

[00:16:30] Eight people need three acres, then you're talking about a greenhouse the size of Singapore to sustain the civilization on Mars. So the scale is insane.

[00:16:38] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Wow. Yeah. And that's like if everything goes right, because it sounds like if they were running out of food, there's just a lot that can go wrong.

[00:16:46] You don't wanna be like, we have exactly enough food, not a pound more for the right number of people. It's just like that's No, you want a nice little buffer there.

[00:16:54] Zach Weinersmith: A hundred percent. And so for example, on day one, I believe a biosphere, one of the women in the program, I think it was Jane Poynter, cut off the tip of her finger in a threshing machine.

[00:17:03] When you're not on Mars, you can actually, they literal leave the sim and go to a hospital. 'cause there was no hospital in the building. There was, you know, first aid and they put her fingertip back on. There was other stuff too, like they were just drawing power off the grid. They didn't have to build their own greenhouse like you would on Mars, you know, so there's stuff like that.

[00:17:19] Of course, there might be benefits to scale. It might be easier to run the system of it's much larger. We just don't know. And that's the big problem here is, is we don't know. And getting an answer to a question like that, like how does an ecosystem evolve over time at different scales is a really tricky scientific problem that'll take a long time to get and nobody is spending much money on it.

[00:17:36] That

[00:17:37] Jordan Harbinger: is quite interesting. There's a lot of other little problems too that I, I took some very choice notes. This is a very difficult endeavor and I, I heard you say, and I love this by the way, going to Mars because the earth is messed up, would be like leaving a messy bedroom to go live in a toxic waste dump.

[00:17:52] That's how incompatible Mars, for example, is with human life compared to

[00:17:58] Zach Weinersmith: earth. Yeah. Yeah. I, I, I think it's really important to hit on this, 'cause I think people watch movies and you get the idea that Mars is kinda like, okay, it's like not great, but it's kinda like Arizona minus error or something, right?

[00:18:08] Mm-Hmm. But it turns out there's just lots of stuff you can't see in those movies or that doesn't get portrayed. And so, like, for example, about 1% of Martian soil is, is a chemical that messes up hormones. And so we don't know what long-term exposure to it does to adults. But what's really scary is you wanna talk about reproduction.

[00:18:24] Like what's that going to do to a developing child? Highly unclear. You'll obviously wanna not have it, but that's gonna be a huge amount of work. And, and one thing we know, one of the most important findings. From biosphere, from the experiments by the Soviets and other ones is that the people in these systems spend all their time just surviving.

[00:18:40] I think a biosphere was like six hour, or I'm sorry, six days a week were spent running the farm just to have enough to eat while starving and to drink and all that. And so, you know, you, if you're gonna also have to be cleansing the soil and you know, running your own power plant, you get in excess of 24 hours very quickly.

[00:18:56] There's other bad stuff about Mars too. I mean, so there are worldwide dust storms from time to time. That's despite the atmosphere being quite thin. So you, you still die if you go outside without a pressure suit. But there's enough atmosphere to whip up duff storms that blot out the sun, which is really bad for solar panels, presumably.

[00:19:11] Oh, yeah. Uh, it's gonna be embarrassing. Uh, so

[00:19:14] Jordan Harbinger: yeah. Yeah. I, I would say so if the perchlorates in the soil don't destroy your thyroid and make you stop growing when you're four years old, the lack of solar energy for days on end or weeks or however long those storms last, that could be a problem. I can see that being a problem.

[00:19:29] Where do we get energy then? Because if solar panels are sort of on off, and, and by the way, is Mars too far for solar panels that we have now to generate? I. Inappropriate amount of electricity.

[00:19:41] Zach Weinersmith: That's a really good question. So it, it is not, but it is pretty far. Right. So I, I, I don't have the numbers in front of me, but I believe it's, you get something like half as much solar power per panel on the surface of Mars.

[00:19:51] It, it's a little complicated 'cause you're farther out, but the atmosphere is thinner and Right. Blah, blah, blah. But the problem is, so theoretically that could be okay. And also because Mars has days that are weirdly earth-like they're about 24 hours, I think 24.7 mm. You would have a day night cycle and you would have light.

[00:20:06] But when you can expect regularly to lose your solar power for weeks at a time, it's like you either have to have an insanely good battery system. Or you need some other regular power source. Right? And so fossil fuels are out. There are no fossils on Mars unless there's a big surprise, right. Awaiting us.

[00:20:21] So you can't really do wind. There have been some zany proposals, but because the atmosphere is so thin, I think they'd have to be just these gigantic, mega, huge structures. You could maybe, you know, tap underground heat like we do on earth. Yeah, geothermal. Geothermal, yeah. That is apparently literally possible on, on Mars.

[00:20:37] But it's thought to be quite difficult. I mean, geothermal, you try to imagine setting up a geothermal system where there's no air and you're in these like wastes outside.

[00:20:45] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. You'd have to be able to drill towards the core of a planet while also basically being in space at the same time. Exactly.

[00:20:52] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah.

[00:20:52] So it's like literally possible. So usually we say that the best option until like some sci-fi stuff happens is you have a good old fashioned nuclear reactor. You ship up some uranium or plutonium. You run your reactor and for all the downsides to that, that some of your audience is imagining, it is a kind of like power source in a box that works night or day as one of the upsides, you're already kind of gonna be bathed in radiation.

[00:21:14] Yeah. At least of your

[00:21:15] Jordan Harbinger: concerns. I was gonna say the radiation thing, like at this point it's like a smoker being like, I think the jackhammer ring outside that bad for my health.

[00:21:23] Zach Weinersmith: That's exactly right. Yeah. Yeah. So I mean, you know, probably what you do is you go out some distance from your habitat, you dig a hole and you put it in there.

[00:21:31] You'll still have to have like people to operate it and stuff. But when you compare that to having to like clean like acres and acres and acres of solar panels in like doom, it's just probably the best option until some sort of, you know, crazy sci-fi tech comes along. I'd like to

[00:21:44] Jordan Harbinger: highlight your earlier point, which is colonizing Mars is not a solution for a messed up earth.

[00:21:49] And I, I like this for a few reasons. One, I think a lot of people are like, ah, climate change can't do anything about that. Plastics in the ocean can't do anything about that. Litter and garbage and lack of recycling and big oil and all this other can't do anything about that. It's fine. We're gonna go to Mars.

[00:22:04] And it's like, again, you're leaving a messy bedroom for a toxic waste dump. This is not just like the, oh good, we get a second crack at things. It's not really like that. We joke

[00:22:14] Zach Weinersmith: like if you had Earth, we actually looked up what is the worst case climate change scenario. Anyone's predicting. Take that and like add nuclear war and any other catastrophe you like, like I don't know, like there's a hole in the earth and demons are pouring out.

[00:22:27] That's still a planet where you can breathe. And where like they have gravity. They have gravity, gravity's nice. We haven't even gotten into that. Gra, you know, the lack of gravity probably has all sorts of bad, long-term effects we don't even know about. So yeah, the, any idea that in the, anywhere in the near term space is gonna save us from any calamity is absurd.

[00:22:44] It's just too hard, too expensive. And also just the general idea that we're going to be launching like millions, billions of tons of stuff to space, requiring hundreds of thousands of skyscraper size rocket launches every day. That's going to improve the environment is just absurd. Yeah, it's unlikely.

[00:23:02] Let's say I, you know, I'm sure there's, there's some space nerd who's angry at me right now,

[00:23:05] Jordan Harbinger: but, well, basically the sub name of this show, the subtext of this show is pissing off bunches of listeners for things you'd never imagine. Like, I get it when I do an episode where somebody's like, Hey, plastic's in the ocean, artist being of a problem as we thought, you shouldn't have let this guy say his thing.

[00:23:18] I get why people are angry about that. I understand why when somebody says Hamas is not a terrorist organization. People are angry about that. I'm angry about that, but the thing that's gonna trigger someone in this episode is gonna be something that you and I both think is completely benign. That's how this works.

[00:23:32] Yes. That's how this works. So don't even try to not piss people off. It's not worth it.

[00:23:36] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah. No, I, I think what I've found is. All ideas about going to space. They're kind of bound up with utopianism. Like, whatever you think is wrong with Earth will be better over there. Mm-Hmm. Because you can get a clean break with your people and fix it all.

[00:23:49] And it's just like there are all sorts of different scenarios and they just don't hold up. 'cause humans are just gonna be people over there only like surrounded by poison.

[00:23:59] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. And unfortunately surrounded by other people. Yes. Which is what happened in Biosphere two, which seems like it was a big problem.

[00:24:05] And in fact, I know you've said that space settlements might actually favor autocratic authoritarian governments. That is a really interesting point. That makes perfect sense to me because it's probably gonna have to start off. Basically like a military outpost, just because the stakes are so high, you can't have people being like, I got freedom of poking holes in the wall if I want to.

[00:24:28] You can't do that. You have to have people that are all rowing in the same direction if you're gonna survive in space. But, and this is nerdy, but it reminds me of there's a Call of Duty, which is a video game. There's an installment where the Mars Settlement Defense Force essentially attacks the earth because they're like, Hey, we don't need these guys anymore.

[00:24:45] We have our own planet. We got our own thing going. And it's a totalitarian military regime along the lines of, I guess maybe Sparta or whatever, I'm a little less worried about Mars settlement defense force attacking as I, that scenario is a little outta mind, but I think you might be right about autocracy in a place like Mars or, or in space anywhere, at least for the first few slash several generations of humans there, because how else are you gonna function?

[00:25:09] How else are you gonna create a society like that? And it's tough growing up in an environment like that ask anybody who defected from North Korea, for example, and it, it's gonna be tough. To transition to what might look like a functioning democracy from authoritarianism, because those values have to be there somewhere behind the scenes.

[00:25:25] And I'm not sure how you do that unless you have really good contact with Earth the whole time. Right? Yeah.

[00:25:30] Zach Weinersmith: I, I, I think there, there's a good case for that. There's a, a scholar named Charles Ell, who writes a lot about this, about, like, as an example, if you're living in a built structure on Mars, there is some source of oxygen under somebody's control.

[00:25:44] Mm-Hmm. In a way that's just not true on earth. Right? No matter, like the worst company town you can imagine, I. Like your boss didn't have control over oxygen. The closest analog sometimes uses submarines, and we actually did, we read some submarine books and we found a case of a guy who at least claimed he tuned the oxygen up or down to like adjust mood in the submarine.

[00:26:04] So like, apparently people are capable of this certain thing, huh? I mean, you

[00:26:08] Jordan Harbinger: hear it from casinos and it's not true apparently the whole Yeah, I, I can see that. Look, I, I mean he who controls the spice controls the universe. That's a soundbite I should have gotten for this show. But it's, if you wanna put down a rebellion in one corner of your space settlement, all you have to do is be like, well, I'm turning the air off.

[00:26:23] If you guys don't calm down. I mean, that'll do it. Yeah.

[00:26:26] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah. You could even, I mean, you know, if you wanna get really nasty, all you have to do is crank the CO2 level up to about one, one and a half percent. People start getting headaches and so you can. Give them carbon, uh, ssis and just make 'em chill.

[00:26:37] Yeah. Oh yeah. So yeah, I know it is a problem. And then that's the question is like, you know, it's one thing if, if a bunch of people wanna voluntarily go live this lifestyle, by all means, but if they decide they wanna have children, then it seems to me to be like an ethical nightmare. Uh, that should probably be stopped.

[00:26:52] I mean, this, this is something we get into. 'cause sometimes we'll, we'll talk about like, well we have concerns about like ethical things. And someone will say, well, you're just a bunch of nies and me and Elon are going to Mars and you can't stop us and you shouldn't be able to stop us at Twitch. I say like, if you just wanna personally go and hurt yourself, that's awesome.

[00:27:09] Have an adventure. I would like to watch the movie. I like reading about like Arctic Explorers. They're kind of crazy, but awesome. But if you're talking about like having children or setting up some kind of rival state structure, these sorts of things, then there's a conversation to be had about what the rights of other people on earth are.

[00:27:26] Jordan Harbinger: You are listening to the Jordan Harbinger show with our guest Zach Wiener Smith. We'll be right back. This episode is sponsored in part by Shopify. Ever wondered about things so incredibly efficient? They seem almost magical. Think of the ease of online banking, the wonder of wireless charging, or the simplicity of contactless payments.

[00:27:42] Now, add Shopify to that list. It's like having an e-commerce Swiss Army knife at your disposal got a brilliant business idea. Maybe it's about selling those trendy sensory bins for kids. Are the much talked about Montessori materials, but where do you begin? Enter Shopify, your global commerce wingman from the instant you set up your online store, Shopify as your trusty guide supporting you at every turn ready to leap into a brick and mortar store.

[00:28:02] Shopify's right there with you with this top-notch in-person point of sale system. And when your orders soar into the millions, guess who still with you? That's right. Shopify. Shopify's checkout boasts the conversion rate of up to 36% higher than other platforms. Shopify powers 10% of all e-commerce in the us.

[00:28:16] They're behind big hitters like Allbirds, RFIs, Brooklyn, and and a host of hustling entrepreneurs in 175 countries around the globe. Sign

[00:28:23] Zach Weinersmith: up for a $1 per month trial period@shopify.com slash Jordan in all lowercase. Go to shopify.com/jordan now to grow your business no matter what stage you're in.

[00:28:31] shopify.com/jordan.

[00:28:33] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by SimpliSafe. As we welcome the new year, it's time to focus on what matters most. Our loved ones safeguard them with SimpliSafe, the system, US News and World Report hailed as the best home security of 2023. We trust SimpliSafe in our home too. It's not just about preventing break-ins.

[00:28:49] It's a comprehensive shield against fires, floods, and other hazards, ensuring timely assistance. We've even installed SimpliSafe at my parents' place for extra peace of mind. Their latest feature, 24 7. Live guard protection is quite amusing. Monitoring agents. Yeah, that's right. Amusing monitoring. Agents can now see and interact with intruders, stopping crimes as they happen, shaming people who enter your house illegally.

[00:29:09] A service exclusive to SimpliSafe for less than a dollar a day. Half the cost of traditional security systems, plus SimpliSafe respects your privacy. Their indoor cameras also have physical privacy shutters, so you know if you're walking around naked. No judgment. Still unsure. Try SimpliSafe risk-free for 60 days.

[00:29:24] If it doesn't win, you over, return it for a full refund. Keep your home and family

[00:29:27] Zach Weinersmith: safer than ever in the new year as a listener. You can save 20% on your new system with Fast Protect monitoring by visiting simplisafe.com/jordan. Customize your system in just minutes. That's simplisafe.com/jordan.

[00:29:40] There's no safe, like simply

[00:29:41] Jordan Harbinger: safe. If you're wondering how I managed to book all these great authors, thinkers, and creators every single week, it's because of my network and I'm teaching you how to build your network for free over@sixminutenetworking.com. I know networking sounds gross. You don't wanna do it.

[00:29:54] This is not cringey, it's down to earth. Pardon the pun. Uh, as for the episode, there's no awkward strategies or cheesy tactics that are gonna make you look like a jerk or make the people that you're trying to keep in touch with feel gross about you. It's just gonna make you a better connector, a better colleague, a better friend, a better peer.

[00:30:09] And six minutes a day is all it takes. And many of the guests on the show, they already subscribe and contribute to the course. So come join us. You'll be in smart company where you belong. You can find the course@sixminutenetworking.com. Now back to Zach Weiner Smith. Concurrent construction gear even function on Mars temperatures.

[00:30:28] Because I look at construction sites around here, and I'm, I grew up in Michigan. I live in California now, and I, I just thought, wow, these guys out here, they have it much, much easier than they did in Michigan. They gotta go in the winter and they're, and then I thought to myself, okay, the winter, now imagine that's way colder.

[00:30:44] There's no air and you'd have to modify the engine, right? You can't run a diesel engine on Mars with no atmosphere, oxygen, whatever. I would imagine. But even then. What about the treads on a bulldozer? What about a crane? Don't those require certain amounts of gravity to stay put and other You have to redesign all this stuff, not to mention just temperature stuff.

[00:31:06] Temperature issues. Yeah,

[00:31:07] Zach Weinersmith: so this sort of thing is really important. One of my favorite cranky rants by an astro guy was he was talking about there are these proposals for melting some of the water on the moon for all sorts of uses, and he was complaining about a proposal that said, you know, we'll use all this water and here's how we're gonna recycle it and all this stuff.

[00:31:23] It didn't mention that part of getting it involved something like an eight mile traverse through the darkness in like whatever it was, negative 200 Fahrenheit on the surface of the moon, which of course has no air among other problems. And there's, I think a kind of like tendency for people who've never had to do this sort of work to think we can just run some numbers.

[00:31:44] Mm-Hmm. As an example, we talked to a guy who had worked on lunar rovers and he said a really hard problem, he's just making a lubricant that can survive you alternating between like 600 degrees of Fahrenheit on a two weeks basis as it does on the moon. And so, yeah, I mean actually once you start thinking about this, it gets really crazy.

[00:32:01] Like if you have something that's depends on a heavy weight dropping, well you have less gravity, right? So you need, you need more weight to get the same oomph when it slams into the surface. Mm-Hmm. And then you just think about like the pressure. So as an example, you in a movie, if your buddy has a problem outside the space station, you throw in the pressure suit and you run out.

[00:32:18] In real life, if you do that, you will get the bends, you'll get nitrogen bubbles in your blood 'cause of the pressure change, and you will just die. You actually have to go into an airlock, and there are different ways for doing this, but something like say a half hour to an hour has to be spent breathing pure oxygen to get the nitrogen outta your system.

[00:32:34] So it's like there's all this stuff that makes sense until you start getting finicky about how it's actually going to work when an actual person has to actually go do the thing.

[00:32:41] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that's interesting. I hadn't thought about that. Tell me about this moon thing. 600 degrees fahr. Does the moon change 600 degrees every two weeks?

[00:32:50] What is, I had no idea.

[00:32:52] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah. So the moon, on the moon a day is two Earth weeks long, right? So meaning like you get 14 days of light, 14 days of darkness, and also no atmosphere, which would kind of spread out the ambient temperature, right? You're just blasted or not. I see. Yeah. So temperatures tend to get really, really, really hot.

[00:33:09] Like hot as an oven, and then really, really, really cold. Much colder than ice. And so obviously that's havoc for a little rover that needs to survive all these conditions. Also, what we do to get them to survive is you put a little bit of plutonium in there to just keep 'em toasty. Hmm. Uh,

[00:33:24] Jordan Harbinger: and, uh, wouldn't want that in my pocket though, as a human, I don't think,

[00:33:27] Zach Weinersmith: well, you know, if you, if you have enough cladding, uh, maybe depend on where you're holding it.

[00:33:32] But, but keep it,

[00:33:34] Jordan Harbinger: keep it family friendly. That's, I'm

[00:33:35] Zach Weinersmith: sorry. Um, yeah. Uh, yeah. So you get these huge temperature swings and it's a real problem for all sorts of reasons. So we go back to like solar power. So you say to yourself, well, can we use solar power? Well, it's gonna switch off two weeks at a time. The only exception to that is if you set up, up at the poles.

[00:33:51] Right. If you're, if the north or south pole, you get grazed by the sun, most of the time there are even a couple tiny areas where like 95% of the time there's light. But it, that's very unusual. Most of the moon is not that way.

[00:34:02] Jordan Harbinger: Hmm. You know, I, I just never thought about the temperature on the moon. I guess I just thought it was probably like a brisk morning.

[00:34:10] In Michigan at worst, not like negative 600 degrees or whatever, negative 400 degrees slash 400 plus whatever it is. I never thought the moon would actually get hot. That for sure is a surprise. Yeah. So that seems miserable and yes, we're flip flopping between the moon and Mars, but I guess at this point, what's the difference?

[00:34:28] It's mostly just settling space. What about the building materials themselves? You know, my house is largely made outta wood and metal. That's fine. When you're talking about maybe zero degrees up to 150 in the most extreme, you know, areas. But. Now we're talking about negative 200 or negative 300 to positive 300.

[00:34:47] You can't just build something out of wood or metal. It's just gonna melt or shatter or whatever,

[00:34:52] Zach Weinersmith: right? Yeah. So there are parts of Mars that are a little more temperate near the equator, but if you're gonna do the moon, you're gonna have these huge temperature swings. The solution is pretty much the same in every mission proposal, which is you need to be under a huge amount of soil.

[00:35:04] So there are different ways you could do that. You could set a sort of tin can to the surface and just, you know, using the construction equipment we just said would be really hard, you know, a huge pile of, of what's called regolith. This messed up soil on the moon on top. And what that does is it just kind of protects you from those big temperature swings.

[00:35:19] Kinda like if you were a mole. A more interesting proposal, which to me is like separate from whether I think it's a good idea, is maybe the most awesome idea, which is the moon isn't really seismically active anymore, but it once was, which meant there used to be flowing lava in places if you've ever been to Hawaii.

[00:35:34] Yeah. Or I'm told they had these, yeah. Yeah. So you've been like lava tube caves, right? Or maybe I Oh yeah. They have those on the moon. They have them on the moon only. They're much, much bigger. Maybe as much as a hundred times bigger. Wow.

[00:35:44] Jordan Harbinger: You could drive any size, well, multiple, a hundred times bigger.

[00:35:48] Insane. Right. That's like a freeway more maybe even

[00:35:52] Zach Weinersmith: to me it's like if you were going to pick a mission for sheer awesomeness just about anywhere in the solar system, sending somebody into one of these would be top of my list. Wow. But from a settlement perspective, the exciting thing would be instead of like landing a tin can and piling stuff on it, or else trying to build stuff out of the surface, you go into this cave and you have some kind of say spray on sealant and you just seal up the cave or a chunk of the cave.

[00:36:17] Then you pump it full of air and whatever else you need and then you've got a little pocket and now you can just build in there. Right? So not everything has to be defended against space. The cave is doing it for you. Hmm. So that's a pretty typical proposal with the reel. That's cool. Yeah, it is awesome.

[00:36:31] Right? I mean, you just talk about like, I'm always amazed people have never heard of these, but my understanding is they were only really understood starting about 20 years ago. There's actually not that much where everybody gets excited about Mars. There's a lot of scientists who are like, why don't we send more stuff to the moon?

[00:36:43] The moon is amazing. Yeah, that's, I

[00:36:45] Jordan Harbinger: just had no idea. They were so massive too. 'cause it's so amazing how big that must be. 'cause those LABA LABA tubes in Hawaii, you can walk through those,

[00:36:53] Zach Weinersmith: right? Yeah. They're like cathedrals.

[00:36:55] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. So something that's a hundred times bigger, you could fit my neighborhood in there.

[00:37:00] Zach Weinersmith: No. Yeah, it's crazy. You can imagine, uh, you know, whole cities, you know, and, and the only real downside, other than like it being difficult to get into these things and there's some questions about structural stability, but it's probably fine, is just that there aren't many. And so, you know, where it gets scary is like if the US goes first and then China says, Hey, you took the best spot.

[00:37:19] I don't know, does it get weird? But yeah, if you were gonna set up a settlement, that would be one of the cooler places to do it. Well, we'll talk

[00:37:25] Jordan Harbinger: about what get weird might mean, because I have a feeling things will get weird with space. Before we get into that though, Mars has a bunch of CO2 on it. Plants love CO2.

[00:37:36] Is there a fit here? Can we terraform Mars somehow by putting plants that eat the CO2 and make oxygen? Or is that just gonna cause all kinds of other issues?

[00:37:44] Zach Weinersmith: Yes and no. Okay, so setting aside total terraforming for a second and I'll come back to it. The big upside to CO2 is, as you say, plants will take it in, build themselves, and then spit out oxygen, which is just great.

[00:37:58] On the moon, there is very little carbon in the soil. This is often skipped, so you literally cannot grow plants in it. You can't do it. Mm. On Mars with that CO2, just floating around for the taking, you can grow plants, they can release oxygen. You do need, and I won't get into the chemistry, but you need a hydrogen source if you wanna also get water.

[00:38:13] But if you have that source, you have water, you have oxygen, you can even make fuel in the form of methane, which is just a flammable gas that you could also use to like fuel up a rocket or make, uh, like fuel for a buggy on the martian surface. So it's incredibly convenient in terms of terraforming, meaning turning Mars into at least something like earth.

[00:38:34] So I don't think just by having plants you could do that. 'cause the atmosphere is really thin. So even if you cracked all the oxygen out of that CO2, I don't think it'd be nearly enough. Typical proposals call for something like slamming, like redirecting comets into the poles of Mars. Or even like a huge amount of nuclear weapons.

[00:38:51] And the idea there is just you're, you're gonna, the poles have water. And so if you spew so much water into the atmosphere, you'll get a greenhouse effect like we're trying to avoid on earth, which would be desirable on Mars to some extent. What would

[00:39:03] Jordan Harbinger: that do though? I'm confused. We would somehow smash a comet or a giant bunch of nukes into Mars.

[00:39:09] The frozen water would go in the air and

[00:39:12] Zach Weinersmith: then what? No, no water vapor's. A greenhouse gas actually. Yeah.

[00:39:15] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Okay, now I see what you mean. So it vaporizes a bunch of water because of the explosion and then the atmosphere. Has water in it. But wouldn't that be temporary or am I just not understanding

[00:39:27] Zach Weinersmith: how these things are?

[00:39:27] My, so I, this, this is getting toward the edge of my expertise, my understanding it would be, it would be literally temporary, but it would still be like a million years worth of atmosphere. So you Oh, I see. You don't have a little time

[00:39:36] Jordan Harbinger: to work it out. Right. So time to figure. Yeah. Buys us some time to figure it out.

[00:39:39] That's. Actually really kind of cool. Yeah. Just to think you could do something like that. I guess you have to do that before you put anything else on Mars because it's gonna be like explosion, like the world has never seen to try and do that to a planet. It seems like something else could go wrong. Like, so it worked, but now Mars is on a different orbit and we definitely can't colonize it because it's way further out or something now, or it's turned weird.

[00:40:04] I don't know. That's one of those geoengineering things where you can't put the toothpaste back in the tube and then suddenly you realize it was a huge mistake and now you've gotta solve that problem. Yeah.

[00:40:12] Zach Weinersmith: And there, there are also, there are people, and I, I feel complicated about this, but who would say, you know, we only have one Mars and it's like a record of everything that's ever happened here.

[00:40:20] And if we, if we changed it drastically, we would just lose all this, you know, potential information

[00:40:25] Jordan Harbinger: forever. Yeah, that's a valid argument in many ways, I suppose. That said. The question is, how much do we care about that versus colonizing another planet successfully? I don't know. Yeah, that's a tough

[00:40:36] Zach Weinersmith: calculation.

[00:40:37] I, I think it's a really tough question actually. I mean, so the moon to me is the more interesting example because the moon is a, like, it's just like a rock. I know that's like a stupid thing to say, but meaning Yeah. How dare you. How do, yeah. But like everything that has happened to earth has happened to the moon, right?

[00:40:51] It's been there with us for eons and eons and eons. So there are records of what has happened to our planet that are gone from our planet because we have, you know, climate and life and the movement of oceans and things that information is so to speak, embedded in the moon. Yeah. Fossilized essentially, right?

[00:41:05] Yeah. Yeah. And so, you know, some of these proposals for tearing up huge parts of the surface of the moon for minerals. I don't think they're plausible in general, but I do think it's worth considering the scientific aspects.

[00:41:15] Jordan Harbinger: Let's talk about mining, 'cause people talk about asteroid mining and, well, I'm gonna get a bunch of, what is it, helium.

[00:41:24] Three from the surface of the, I, I don't really even know what that is, but tell me about that, the valuable elements of the moon. Why, why is that not a thing that you think is possible?

[00:41:34] Zach Weinersmith: Right. So there's a couple things going on here. So yeah, we, we can talk about moon mining in particular and then I can try to expand out to the other places.

[00:41:41] So in order to justify getting something off the moon, it has to be extremely valuable. Like it has to be a small thing that's quite valuable because it is so expensive to go to the moon. Even with the modern price drops, like there's a lot of other stuff that has to go on. You still need a spacecraft and a lander and trained people and it's quite dangerous.

[00:41:59] In 2017, there's a scientist named Michelle Van Pelt and get this almost verbatim, but he said something like. If there were bars of gold on the surface of the moon, it would not be worth it to go get them. Really? Wow. So there's just not enough like density of value in gold? Maybe if there were like, you know, diamonds, I don't know what it would take, but the point is there's not.

[00:42:17] Right. So there's been this desire to find some reason to go to the moon, other than it just like showing up the Soviets or being generally awesome. And people just haven't come up with that much, I don't think anything that's convincing you will sometimes hear people say helium three. Yeah. Which, without getting into the details, uh, but it does come up a lot.

[00:42:33] What is it? You know, so there's helium, the usual helium, the stuff you get in a balloon is helium four. Yeah. Helium three just is a different amount of neutrons. It's what's called an isotope is just a different form of the same element, but it has certain qualities that make it useful. One, it has medical applications, it's just useful for some screenings we do.

[00:42:48] But the usual thing people say is that you could use it for a certain type of fusion drive. And I can get very nerdy about this, but I will just say, mm-Hmm. It's sort of like we already can't do it. Easier version of fusion, uh, that's in a lower temperature. So like scaling up to helium three fusion. Plus adding in that you have to get it from the moon is like showing off or something.

[00:43:08] It's like doing fusion like while doing a back flip, like why are we doing this? And so if you wanna get really nerdy, there's a paper we talk about in the book, but the basic deal is like it's for a spacey thing. We probably won't build and don't need to build and anyway, right now can't build. But also you can get helium three by other processes on earth without going to the moon.

[00:43:25] I think there's just a really strong desire for there to be some kind of moon economy 'cause it would be awesome. I think people queue a lot on the age of exploration. Like they have this idea that it'll be like the 16 hundreds or the 17 hundreds when people sail from Europe to India. But the difference is India was this vast, rich place full of people with awesome stuff and the moon just isn't.

[00:43:45] Jordan Harbinger: It's a big rock, like you said. So nonchalant, so callously,

[00:43:50] Zach Weinersmith: sorry. It's a cool rock. Yeah. And then so, so people, you know, someone out there is saying, okay, shut up about the moon, but the asteroids, there's whatever, $700 trillion worth of iron or whatever people wanna say. And in some sense that is literally true.

[00:44:03] Right? But you could also say that about like earth's core, which is made of

[00:44:06] Jordan Harbinger: iron

[00:44:06] in

[00:44:06] Jordan Harbinger: nickel. Yeah. There's like 20 trillion tons of gold in the core. I made that number up. Right? It's something like that. It's just massive.

[00:44:13] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, so there's, there's more earth than there is massive asteroids.

[00:44:17] So almost by definition there's more value of stuff in the earth. But the point is it definitely has value if it can be got in a profit. And right now it is extraordinarily expensive. So people have this idea, 'cause they watch Star Wars. If you go to an asteroid belt, it's just a wash in these big potato shaped rocks and you need to go get one.

[00:44:32] Actual asteroids tend to be what are called rubble piles. They're these sort of loose agglomerations of dust and rock. They're very hard to capture or land on. Also, if you were on one to the extent you could be on one with, with the microgravity, you wouldn't be able to see another one. Typically, they're quite sparse on the human scale.

[00:44:48] Mm-Hmm. And, and the stuff in them is like regular stuff. Okay. There's not like one made of diamonds. The most valuable ones are they have what are called PGM Platinum group metals. So just imagine there's a high concentration of platinum, and so that sounds very tempting, but there's still low concentration.

[00:45:02] In general. You still have to refine out these rocks to get this platinum. There's just not that many of these super desirable ones that are relatively getable and valuable, and so it's, it is just not really a serious industry. Maybe one day if we're like awesome at space and we wanna build giant spaceships, it is handy that there's already mass that's outside of Earth's gravity pole, but that's it.

[00:45:23] The idea that we're going to get rich 'cause of asteroids, I think is not serious.

[00:45:26] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that, that always sort of struck me as something that didn't make a ton of sense, but I thought, oh, maybe there's stuff on there that we really can't get. I did some research for an episode on gold, and I just remembered the statistic is there's enough gold in earth's core to coat every bit of land on earth with a 20 inch thick layer of gold.

[00:45:46] So you don't need to go anywhere other than the core of the earth for gold. I guess the question is, is it easier to get to the core of the earth and refine that stuff than it is to go to Mars and or to the moon or or an asteroid? And honestly, I don't have the answer to that. My gut says yes, but I don't have a clue.

[00:46:03] So my guess is not worth anything.

[00:46:05] Zach Weinersmith: The other big thing to note there though is if we had all that gold, it would not mean we were all rich. Right? 'cause the, the value of gold would go to nothing. Yeah, it'd crash, right? Yeah. So we use the example of like, so if you go back 200 years, aluminum is really valuable.

[00:46:17] The tip of the Washington Monument to this day is aluminum. 'cause that used to be fancy, right? Right. But then industrial processes made it cheap and that's great. Like airplanes use aluminum. I'm the microphone. I've talked to him, I'm sure uses aluminum. Aluminum is awesome. But it doesn't mean like I have like aluminum foil in my kitchen.

[00:46:32] It doesn't make me rich. It makes my life better. But it doesn't end poverty. Like people cement.

[00:46:36] Jordan Harbinger: What'd you show off with your aluminum? I have aluminum foil in my kitchen. I threw some away yesterday. That's right. Trash. I, I did this fricking guy. That makes a lot of sense. I mean, gold has industrial uses, especially when it comes to space.

[00:46:49] 'cause it doesn't corrode and all that stuff. But if you suddenly have another, let's say trillion tons, you got 5% of the gold outta the earth's core and you have a trillion tons of it. Now it's. You're making Coke cans on of gold 'cause Exactly. It's so damn cheap.

[00:47:02] Zach Weinersmith: And we're all better off in that world.

[00:47:03] Right? But the idea that poverty is over or that you can just like take the raw number, whatever that is, worth the quadrillion dollars and say that like it's as if we got that money, it doesn't work that way.

[00:47:13] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. Actually, I'd love to know more about the economics of mining and extracting resources in space.

[00:47:18] Because even if, let's say we get a good modular nuclear reactor up there and we we're ready to build, where do we get raw materials and building materials? Do we have to ship them from Earth or are we able to rip stuff outta the ground on Mars or the moon and use that? Is there metal in there or is it just like, no, you've gotta fricking FedEx this stuff from Alabama like everybody else.

[00:47:42] Zach Weinersmith: Yeah. So if you have to boost it from Earth, that's really bad. The usual proposals are what's called ISRU in C two resource utilization, just meaning a used local stuff. And there's a kind of danger here, right? Okay. So the moon has titanium, has magnesium, has silicon, has all sorts of stuff. There was a, a thing that made a splash recently were some people at Blue Origin, which is Jeff Bezos's Rocket Company.

[00:48:05] Mm-Hmm. Made solar panels using this little machine that used, I guess, you know, moon like soil. The problem is it's incredibly energy intensive to do a lot of this stuff. I'm not saying it can't be done, it is going to be quite tricky, but yeah, I mean, so part of why we're pro Mars, if you are going to do a space settlement is that Mars has everything you need.

[00:48:25] So as I said a minute ago, moon is carbon, poor human bodies are about 20% carbon. Plants are, are generally higher than that. And for people who don't remember high school physics, you can't just get more carbon. You can't like shape stuff into carbon. Carbon is made in the stars. You have what you have. So if you have to boost carbon from earth to the moon, you're just, it's not gonna work.

[00:48:45] It's like having to boost a farm rather than ameliorating local soil. Right? Yeah. Whereas Mars has what you need. Now, I get frustrated sometimes 'cause people will say there's titanium, therefore we can have titanium structures. But like, ugh, titanium is really hard to work with that you actually need a whole sort of industrial facility if you're going to make this work.

[00:49:01] Which is, I'm not saying you can't do it on Mars, it's just gonna be extremely difficult. And, and you know, we never talk about earth like this. So like the, I'm looking at my backyard. There's absolutely some amount of titanium in the soil here. That doesn't mean I can have I-beams made of titanium. Right.

[00:49:17] You know, on earth, when we talk about getting metals, we find places where it's at high concentration. Even for something like aluminum, we look for box site right as a precursor

[00:49:25] Jordan Harbinger: and then we say, okay, it's gonna be mine in West Virginia, shipped off to China for refining that is gonna get shipped off to three more countries wrapped in plastic every single time to take advantage of their expertise and economies of scale.

[00:49:38] And you have to transport all that to another planet, which is not, again, not impossible, but just we often forget that like the Apple store doesn't make your iPhone.

[00:49:49] Zach Weinersmith: It's, it's such a good point actually. So very late in writing this book, we were talking to a developmental economist about this, so usually when people talk about the space economy, they talk about resources and he said, you know, you should see this report from the World Bank, which says 97.5%, I think it was, of all human wealth is not in natural resources.

[00:50:08] Right, and, and natural resources in the sense of like stuff in the ground, not things like rainforest or whatever, right? So about two and a half percent of all of our wealth is that, that kind of stuff. And actually 90% of that is fossil fuels, which don't exist in space. People tend to drastically overestimate the importance of minerals, I think, because you go to the gas pump and it like kills you when it's up 50 cents.

[00:50:28] But then you pick up your iPhone, which is made of like, you know, plastic and a little glass and is of extraordinary valuable. And, and you don't think about how cheap it is. But actually, like most of the wealth we have is those processes you just described where you have like factories and you have people with ideas and you have these complex processes for making microchips.

[00:50:44] That's where the money is. You know, the minerals, you gotta have 'em 'cause stuff has to be made of stuff. But it's not where most, I feel like this is like one of the most optimistic facts I ever heard. It's like, like the real wealth humans have is just coming up with stuff and making institutions for building

[00:50:57] Jordan Harbinger: things.

[00:50:57] That's actually a bonus, right? Because that means because we can ship our ideas. That's one of the easier things to communicate or move to another place, I guess, if you really think about it, but it's not quite all the raw material that we actually need to succeed. You mentioned growing food and space and how difficult this is.

[00:51:16] I guess quantity would be tough. You mentioned the biosphere. Two people working on the farm six hours a day just to make starvation level rations. What about actual nutrition? Because let's say you're, you're managing to grow all these plants and whatnot, you still, were they growing animals there and slaughtering them and getting enough nutrition?

[00:51:33] Or was it like they're just existing on soy? That's

[00:51:35] Zach Weinersmith: a great question. So the truth is, I should say, um, biosphere two probably could have been optimized a lot. So without getting into the details, it was kind of run by these crazy Captain Planet types, hippies know beyond hippies, like proto Silicon Valley kind of zany.

[00:51:50] Anyway,

[00:51:50] Jordan Harbinger: this is the eighties when they ran that,

[00:51:52] Zach Weinersmith: was this the eighties or the nineties? Nineties, but okay. They're part of a group that kind of comes outta the late sixties and early seventies, sort of proto Silicon Valley.

[00:51:59] Jordan Harbinger: Um, it sounds like some, what is it as, so like Redwood forest culty types, and they're like, whoa, let's live in a biosphere.

[00:52:05] Zach Weinersmith: They were called the Synergists. They lived on a ranch. You can look it up. It was, it was like that. Yeah. And so biosphere was about three acres, only about a half an acre was what's called intensive agriculture. The rest was like a. Biomes, like they had a ghost forest or ghost desert. I don't really know what it is.

[00:52:21] Uh, they had like a coral reef, I guess it's very captive planet. So by the end, they were actually moving ag stuff into those zones. So there probably was a lot of optimization to do. Um, they did have animals, but they actually had a lot of trouble with animals. So, for example, this is a true story. They wanted to have pigs.

[00:52:37] They were gonna have potbelly pigs because pot belly pigs are like a small manageable pig. But then it was like that period where potbelly pigs were like everybody's favorite pet. And so they thought the PR would be bad. Oh yeah. Yeah. They got this other type of pig, I forget from where there was like a pygmy species, but it was just kind of wild and I guess it ran around killing stuff.

[00:52:54] So they ended up eating them and so I, I go down the line. They had other problems. At one point, the crew, which was an all white crew, I. And I only mentioned that because they were eating tarot. They're grown tarot. They didn't know how to process it. So they're like slightly poisoning themselves. What is that?

[00:53:08] Tarot? Oh, it's a root. Oh, Tarro. Tarro. I'm sorry. Yeah, I'm saying

[00:53:11] Jordan Harbinger: it Ryan. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. No, you're, or you're saying it right and I say it wrong. Um, Tarro. Yeah. That like potatoe crap that Taiwanese people love to put in their bubble tea. Yeah,

[00:53:21] Zach Weinersmith: yeah, yeah, yeah. Unfamiliar stuff. Yeah.

[00:53:23] Jordan Harbinger: It's good stuff. I do not like that for the record.

[00:53:25] Oh, don't gimme a tea tarot in it. No, thanks. My wife loves it. Get a little

[00:53:28] Zach Weinersmith: potato in your drink. Drinking

[00:53:30] Jordan Harbinger: potato. It's no. What are you doing? Way to ruin, you can ruin any meal with that potatoes included

[00:53:35] Zach Weinersmith: for that matter. Yeah. So you, yeah, it's funny. Uh, you have to process it a little or it's toxic, right?

[00:53:41] It's just like a lot of foods when you get it fresh, uh, or raw, it needs a little work. They didn't know that. They were all, I think American and British. And this was like the nineties before, like food was good and they, uh, had to actually call someone. They got connected to a guy like in Puerto Rico, had a recipe and then it was okay.

[00:53:58] So there were a lot of kind of like little stupid things. Hmm. So nowadays, if we reran the experiment, probably what you do is have it be almost entirely intensive agriculture, assuming that could support enough oxygen. Then you might not bring any animals. So as a general rule, the bigger the animal, the less, less efficient it is at like converting input to output.

[00:54:17] So in other words, like to get a whole cow worth of meat takes a huge, huge, if you've ever seen cows grazing, they just all day long just to get this one cow. It's insane. Whereas if you wanna to survive off crickets, if you could stomach it, it's much more efficient. Crickets

[00:54:32] Jordan Harbinger: aren't that bad. I've eaten many insects, you know, in Japan or whatever.

[00:54:36] Yeah, it's fine. I wouldn't necessarily want it every day. I wouldn't want anything every day. But if I were starving, you could eat cricket. If I had to choose crickets or tarot, I'm

[00:54:47] Zach Weinersmith: choosing crickets. That is a bold choice. That's the thing that's gonna piss everyone off, is that's where the email

[00:54:52] Jordan Harbinger: people are gonna start emailing me cricket based foods and you know what, I'm here

[00:54:55] for

[00:54:55] Jordan Harbinger: it.

[00:54:55] Send it to me. I'll send you my address. Yeah,

[00:54:57] Zach Weinersmith: yeah. My, my daughter, when she was four, she tried crickets and she was like, these are great, the heads are really crunchy. And I was like, I can't even watch you roast crickets. This like, oh my god, you

[00:55:05] Jordan Harbinger: can eat things like that though. Like I, when I was in Cambodia, I said I was hungry and the girls I was with decided to sort of play, I guess you'd call it a trick.

[00:55:13] They went and they bought me a big paper bag full of tarantulas. There you go. Like roasted tarantula. And you know what? They were good. They were really good. I was quite hungry and possibly a little bit drunk, but I ate a whole bag of tarantulas. That's crazy that they probably bought off the roadside and I, God knows where that guy got 'em and I didn't get sick.