Michael Shermer (@michaelshermer) is the founder of Skeptic magazine and several books on the nature of belief. He’s the Director of The Skeptics Society, a non-profit dedicated to the promotion of science, reason, and critical thinking. He joins us to discuss why people believe weird things. [This is a rebroadcast that originally aired in 2016.]

What We Discuss with Michael Shermer:

- How do beliefs form and persist even when we know they’re wrong?

- Why do skeptics (and restaurant owners) scowl at the mention of Uri Geller?

- Why are smart people even more susceptible to faulty beliefs?

- How do our genes influence our political and religious beliefs?

- What’s the difference between a skeptic and a cynic?

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

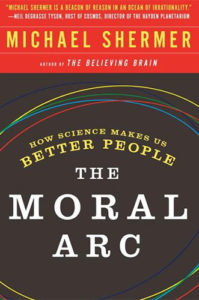

Michael Shermer, founder of Skeptic magazine, Director of The Skeptics Society, and the author of several books, including The Moral Arc: How Science Makes Us Better People, joins us to examine why we’re hard-wired to believe weird things and how we can use science and develop the critical thinking skills to question everything skeptically without succumbing to cynicism.

Listen to this episode in its entirety to learn more about confirmation bias as motivated reasoning, how Michael Shermer was able to debunk so-called psychic medium John Edward in a few sentences (and why Edward is still touring among his true believers in spite of this), how cold reading works, why we gravitate toward news and entertainment that reinforces the beliefs we already have, the difference between profiling and running the data, how sensory data creates beliefs, why we believe first and seek confirmation for our beliefs later, how evolution has led to moral tribes, the genetics behind personality temperament, why we get a rush of dopamine when we come across information confirming what we already believe, how different political groups can view the world so differently, why people double down on their faulty beliefs, and lots more. Listen, learn, and enjoy! [This is a rebroadcast that originally aired in 2016.]

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

Miss the show we did with the late and sorely missed Kobe Bryant — basketball legend, family man, and multimedia mogul? Catch up here with episode 249: Kobe Bryant | Dissecting the Mamba Mentality!

On the True Underdog podcast, entrepreneur Jayson Waller and his high-profile guests share motivational tips, inspiring stories, and business-building lessons to help each listener grow in their entrepreneurial journey. Listen here or wherever you enjoy podcasts!

THANKS, MICHAEL SHERMER!

If you enjoyed this session with Michael Shermer, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Michael Shermer at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Skeptic

- The Moral Arc: How Science Makes Us Better People by Michael Shermer

- Skeptic: Viewing the World with a Rational Eye by Michael Shermer

- Other Books by Michael Shermer

- Michael Shermer | TED Talks

- Michael Shermer | Website

- Michael Shermer | Twitter

- Penn & Teller | Showtime

- James Randi Exposes Uri Geller and Peter Popoff | Daily Motion

- Michael Shermer Debunks James Van Praagh & Psychics | Skeptic

- The Full Facts Book Of Cold Reading by Ian Rowland

Michael Shermer | Why We Believe Weird Things (Episode 492)

Jordan Harbinger: Coming up on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:02] Michael Shermer: You know, we know about the research from behavior genetics that people are highly genetically inclined to be either conservative or liberal or religious or not very religious. Well, there can't be a gene for being a Catholic or a Democrat. No. What it is its genes code for personality temperament. Like I like this kind of worldview because it makes me feel good. And all these other people that are in this group, this tribe, they're like me and I like being around people that are like me. It feels good. And that's where the genes and the emotions kind of meld there. And it ends up being that, well, we call our moral drive Democrats or Republicans or Catholics or Protestants or Buddhists. And the culture ends up sorting it out in the details but the deeper part is how we feel about being a part of that group. And we kind of migrate to it.

[00:00:58] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We have in-depth conversations with people at the top of their game, astronauts and entrepreneurs, spies and psychologists, even the occasional mafia enforcer, drug trafficker, or neuroscientist. Each episode turns our guests' wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better critical thinker, especially here today.

[00:01:26] If you're new to the show or you're looking for a handy way to tell your friends about it, we now have the episode starter packs. These are collections of your favorite episodes organized by popular topics that will help new listeners or somebody you're sending the show to, of course, get a taste of everything we do here on this show. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start to get started or to help somebody else get started here with us. And of course, I love that when you do that, when you're sharing us. That makes my day. So please go ahead and do that.

[00:01:55] Today, one from the vault, we're talking with Michael Shermer, founder of Skeptic Magazine and author of several books on belief. He's a writer for Scientific American and a multi-time contributor to Penn & Teller's show Bullsh*t on Showtime if you all remember for that. Today, we discuss how beliefs form in our brain, why they persist, even when they're wrong and sometimes even when we might know that they're wrong. We'll also dive into why people believe weird things and why smart people sometimes are even more susceptible to faulty beliefs. Last but not least, how our genes can influence our political and religious beliefs. Lots to cover on the show today.

[00:02:31] And if you're wondering how I managed to book all of these great authors, thinkers, and creators every week, it's always because of the network I'm teaching you how to build your own network, whether for business or pleasure over at jordanharbinger.com/course. The course is free. I don't need your credit card info, none of that. Most of the guests on the show, they subscribe to the chorus. Come join us, you'll be in smart companies where you belong. That's jordanharbinger.com/course. Now, here we go one from the vault with Michael Shermer.

[00:02:59] Michael, tell us what you do in one sentence.

[00:03:02] Michael Shermer: Oh, well, my day job is I'm the publisher of Skeptic Magazine and a director of the Skeptics Society. We're a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to science education and the promotion of science, reason, and critical thinking. I also write a monthly column for Scientific American called Skeptic, dealing with the same type of topics we covered Skeptic Magazine.

[00:03:24] Jordan Harbinger: You've been on TV a lot. I mean, you've been on Penn & Teller's Bullsh*t. You've been on Oprah Unsolved Mysteries. What else? I mean, there's so much that I've seen personally and there's probably a lot that I haven't.

[00:03:35] Michael Shermer: Yeah, I've pretty much done all the talk shows and Colbert Report twice. And it's just part of my job though, to sort of reach out to the media to get our message across. That, in many cases, there are explanations and answers for a lot of these mysteries. People just don't know them. And that the way we arrived at those explanations is through science and reason. So, you know, that's kind of always my regular job doing that. So yeah, just a lot of the media stuff. I just recently did Neil deGrasse Tyson's StarTalk, and we started Skeptic in the early '90s, when you were still pretty much restricted to the major networks and CNN. But now there's just untold avenues to get ideas out there, like podcasts, for example. You can really reach everybody at some point, you can't do it anymore like in the old days where you just make one appearance on NBC and the Tonight Show and you've reached everybody, but it doesn't work that way anymore, but still there's kind of a democratization in science in the sense that the media penetrates everywhere now. And that's a good thing. So even though it also promotes crazy ideas like 9/11 truthism or conspiracy theories or aliens or whatever, because they all have their own web pages — but not the aliens, but the people that believe in aliens.

[00:04:56] Jordan Harbinger: Or do they?

[00:04:57] Michael Shermer: But that just gives us skeptics and pro-science people more channels also to promote what we think is good thinking.

[00:05:05] Jordan Harbinger: What's the difference between a skeptic versus just a cynic, someone who doesn't believe in anything or tries to poke holes in everybody's ideas and spoil everyone's fun?

[00:05:13] Michael Shermer: Oh, well, yeah, that word cynic for some odd reason gets conflated with skeptic. You know, they don't mean anything even remotely the same and they don't even really sound the same. Although I guess in some people's minds, they just think of skeptics as being curmudgeons or deniers. It's a little bit like what you hear with people that are skeptical of global warming. They call themselves skeptics although most scientists call them global warming deniers. So what do we mean by that? Well, skepticism is not a position you just automatically take on all claims a priority. It depends on the evidence of each particular claim.

[00:05:51] So think of it as the no hypothesis in science, your claim is not true until you prove otherwise. And once you provide evidence, then we reject the null hypothesis and assume that your idea could very well be true. And that's how we treat all claims. So it's not that there can't be a Bigfoot and you say, "I believe in Bigfoot." I say, "Well, that's nice, but you know, show me the body." We just have to have the evidence for it. You know, same thing with ET, aliens. You know, they might be out there. They might have come here. We just need to see the evidence for it before we decide definitively what we're to believe in it.

[00:06:23] So skepticism, you know, you can be a global warming skeptic, or you can be skeptical of the global warming skeptics. It's really more of just an approach to claims. It really just comes down to it's just science. It's just a scientific way of thinking. The scientists are skeptics, skeptics take the scientific approach. They're really one in the same.

[00:06:41] Jordan Harbinger: How did you initially become a skeptic? Because according to your work, you were very religious when you were younger and then suddenly or not so suddenly became a skeptic.

[00:06:51] Michael Shermer: Well, I've always been interested in science since I started college. My first class in college was a class in astronomy. And that got me excited about methods of science. And the physical sciences were not going to be the way for me. I wasn't good enough in math to get through calculus and all that. So I switched to other areas. I was interested in evolutionary biology, psychology, but all along the way, this was in the '70s, interest in the paranormal was really spiking, sort of on the heels of the '60s, spiritualist movement and the rejection of mainstream religion, but the rise of alternative religion or spiritual movements, which envelops the paranormal and what we would call a lot of the pseudosciences.

[00:07:34] But, you know, the belief that there's something else out there, some kind of spirit or power, some sort of untapped forces that might be at work that science could explore. So I thought, well, you know, there might be something to that. When I was in graduate school, Thelma Moss had a lab at UCLA that was running experiments on the paranormal Kirlian photography and auras and chi power and acupuncture and acupressure, and you know, all those sorts of alternative modalities. And I was pretty open-minded to it. I thought, well, you know, I'm a mere graduate student and here are these PhD scientists studying the paranormal, maybe there's something to it.

[00:08:13] But it was about that time that the modern skeptical movement got started when people like Paul Kurtz and Ray Hyman and James Randi, and a few others started really looking at the research that these scientists were doing and saw that there was some deep flaws in it. That is the rats were running the experiments. In the case of Uri Geller, you know, he was kind of running the experiments for the psychologists and manipulating them in a way that made them come out a certain way, much like the magician does.

[00:08:41] Jordan Harbinger: Tell us who Uri Gskieller is? Because I actually have his name written in my notes to ask you about, but we might as well jump there now.

[00:08:48] Michael Shermer: He is still alive, but at the time he was a pretty famous Israeli spoon bender and he called himself a psychic or, you know, an energy worker or whatever, but he claimed that he could bend spoons. He had psychic telekinetic power. When you see the early footage of him, some of it is kind of crude by today's standards of what we see in magic, but it was pretty impressive at the time. And people were not familiar with the spoon bending act. In fact, it wasn't something that magicians routinely did. He kind of made it popular. He sort of invented it as a routine, but instead of calling himself a magician and appearing on Penn & Teller's Fool Me, a reality show, which didn't exist at the time or appearing at the Magic Castle where magicians could see his new act and applauded and admired his skill. He said it wasn't magic. That it was actual psychic power.

[00:09:40] So that's where the lines began to get drawn between the paranormal and experimental scientists who wanted to know. This guy is making a claim that it's something other than magic entertainment magic. So that's kind of when the modern skeptical movement got started. If you think of Houdini as sort of precursors testing psychics during the spiritualist movement at the turn of the 20th century, this is the next incarnation, triggered by this Uri Geller. He was hugely popular. I mean, he was on the Tonight Show, all these major talk shows and he was quite the media star.

[00:10:15] His claims then carried a lot of weight with people that believed in the paranormal because he could provide actual, empirical evidence. Here he is, he's doing it, watch. Can you explain it? No. Okay, well then, it must be real. So one of the things that people like Randi and Ray Hyman did was to figure out how he did it and then duplicate it and then say, "We're duplicating that using the magic. So if he's doing it with some other means he's doing it the hard way." And that really launched the modern skeptical movement. Geller are still around. He's pretty much admitted that it was a magic trick, but not quite. He hasn't come out fully and said, "I was scamming people." He just king of does the wink, wink, "We all know what I was doing," sort of routine with magicians now.

[00:10:58] But of course, the whole movement has moved on to other things, you know, alternative medicine and things like that. But the foundation is still there. There's still people that believe in the paranormal.

[00:11:08] Jordan Harbinger: Did he even go kind of corporate with it? And he was flying around laying low for a while saying, "Oh, I'm finding oil in the ground for companies to drill for oil and minerals." I mean, how do you pull off something of that nature? That's so vast that you're even fooling, supposedly fooling oil companies and mineral and mining companies.

[00:11:27] Michael Shermer: Yeah, well, yeah, he wasn't laying low. He was just making more money at it quietly. Because you can make a lot more money if chartered by a major corporation to find oil than you can entertaining kids at a birthday party or a TV talk show. I mean TV talk shows, they don't even pay their guests. That was his way of making it lucrative. How does he do it? So how does he find oil? Well, the same way that dowsers find water. First of all, there's oil all over the place. There's water all over the place. So if you dowse enough places, you're bound to get some hits. The people that are paying you remember the hits, they forget the misses. You have your excuses that it's not a hundred percent perfect. And people don't know about statistics and probabilities and, you know, by chance you're bound to get a certain number of hits, like flipping a coin.

[00:12:14] You know, if you predict that you'll get five heads out of 10, you know, you're going to get a lot of right, you need to get a lot of hits, correct answers, just by chance. So you have to do better than chance. And the only way to do that is to set up controlled experiments where you're blinded and the subject is blinded to the conditions and then you run the experiment. And you know ahead of time what chance results would produce. And then you ask, well, how many does he have to get right to be above chance? And that's pretty standard experimental psychology protocols, which people like Ray Hyman who was an experimental psychologist is really good at.

[00:12:46] So in the '80s and in the '90s, there were a lot of those tests done to show that people like water dowsers or oil dowsers or whatever could not do better than chance. They were getting the predictable number of hits but the problem is the average person doesn't know about any of that. The confirmation bias kicks in. They remember the hits; they forget the misses. Their beliefs get confirmed, and the disconfirming evidence is just dismissed. Well, those are just misses. You know, everybody misses once in a while. Like the psychic that rattles off a dozen names and two of them have some connection. The subject just remembers the two and forgets the other eight. So it's our job as skeptics and scientists to call attention to the missing ones. Not just the hits, but the misses.

[00:13:28] Jordan Harbinger: What does the fact that people believe in that say about belief in general?

[00:13:33] Michael Shermer: Well, that our brains are wired to be more like lawyers than scientists, that is to marshal evidence, to support your clients and the metaphor of the client is our beliefs and to ignore the evidence that doesn't fit. You know, if the glove doesn't fit, you must acquit. You know, that's in a way how our brains operate. We only want to read articles or listen to talk shows that support what we already believe and just ignore the stuff that doesn't seem to fit. And everybody does it. The confirmation bias sometimes it's more broadly, called motivated reasoning. We're motivated to reason our way to finding what we want to be true, to be true. And this includes scientists. They're no different, but the differences is that science itself doesn't allow you to do it.

[00:14:18] The protocols require you to be blinded to the conditions so that you don't know which box has the water in it, or the oil or whatever, and neither does the subject. You know, the boxes are numbered and so forth. It's all done in a way to work around the confirmation bias. So that does, I mean, maybe you have a bias against psychic power and it really exists and you're missing it. That would not be good either. So we have to just do it fair in a way, because we know now that the human brain is not unbiased, it definitely filters data in a way that contaminates our conclusion. Entire scientific process for centuries has been refined to work around the psychological cognitive biases that exist.

[00:15:00] I did a show with John Stossel on ABC 20/20 on Van Praagh. It was back in the '90s and they rented a house in LA and he did readings all day. And the one for 20/20 was in New York. There was another one, the History channel in LA at a house. Anyway, I've seen him twice all day so I know all his tricks now. The one for 20/20 in New York, I actually had a little counter and I counted every single comment he made and how many hits he got. That is how many times the people went, "Wow, that's incredible." Or, "Yes. And there's a connection there," whatever, and he was less than 10 percent right. But afterwards, when we debriefed the subject, filmed them, asked them how they liked the reading they got, they would always instantly remember those 10 percent hits. "Oh, he got the name of my grandfather and he got that he died of cancer. He got this, he got that." And they completely forgot about the hundreds of things he said that had no connection to them at all. In fact, I had a hard time remembering the misses, which is why we recorded it so that we could go back and go, "Okay, let's hear it. He says this thing about this." "Oh yeah, yeah. That had no linkage at all." "And this one and this one and this one." He's like, "No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no." People forget that stuff.

[00:16:11] So with a big audience like that, you can just see him work in the crowd. You start very broad, you refine it, and you get it down to a couple of people, then down to maybe one person, even that's very much like how a hypnotist works or a magician might work. And he works the crowd to see who's really on board for being part of the drama, who's not going to be too skeptical, who's not going to be grumpy, not going to be sitting there with a scowl on their face. Like, "I don't want to do this," but if you have a couple of hundred people to start with, "You're going to find a couple of super gullible people. Totally into it." And then you just work your magic. And the magic is what's called cold reading.

[00:16:43] Jordan Harbinger: So how does the cold reading actually work?

[00:16:46] Michael Shermer: So you start off very broad. You're literally reading somebody cold who you've never met. So you start off broad and positive. "I sense you're a very intelligent, thoughtful person with a good sense of humor. You enjoy the company of others. People like you a lot and so forth." And no one's going to stop you and say, "No, you know what? I have no sense of humor, no one likes me and I'm kind of a dullard." You know, those kinds of positive comments work for everybody and you just start refining it more and more.

[00:17:12] Like, the four areas that people care most about love, health, money, career. So you just go through the categories. "I sense you in a relationship right now, and one of you is more committed than the other." Or, "There's some financial tensions in your budget or in your household right now." Or, "You're thinking about changing jobs or changing careers. I see travel. I sense that there's some concerns about your health. You have some aches and pains or weight concerns." You know, you just kind of go through those categories and that can eat up a good 15 to 30 minutes, just working those four. Because if you have somebody who's reasonably talkative, they will open up and say, "Oh yeah, yeah. You know, I'm in this relationship right now and she wants this and I want that." They go on and on, and then later you bring some of those details back in and they'll forget that they told you those details and they'll think you got them from an eye. It's quite remarkable to see this unfold.

[00:18:02] So that's a cold reading and you can keep refining it. And there's this book called The Full Facts Book of Cold Reading by Ian Rowland. And he has in there, hundreds of things you can say, you know, he's like, "Well, I sense that you have an earring and you're missing the match to it. So you're hanging on to it." Or to a guy, "There's some power tools in your garage that are not working, but you're going to fix it." Or, "There's a Post-It note on your fridge that's out of date. You can take it off." You know, just hundreds of things like that. "I sense something about a white car, a red dress, a scar on your knee," and just on and on and on. And you can't believe that this stuff works, but it really does. I've tried it. And you just say it in a kind of a provocative, "I'm getting something about a white car. I don't know what this means. There's something about a white—" "Ooh, oh yeah, my first car was a white car. The red dress, I went to my first prom in a red dress." So the person actually doing the reading is not the psychic, but the person sitting there. Because the psychic just asks a lot of questions or throws a lot. "I don't know what this means, but I'm getting this," and you throw it at them and the person will sit there and you can see them thinking, "Okay, let me see what is — ooh, wait, wait, I know what it is."

[00:19:10] Jordan Harbinger: So you're throwing a bunch of things at the wall to see what sticks and the other person does you, the favor of making a picture for you with that stuff. And then you just take credit for it as the fake psychic.

[00:19:20] Michael Shermer: Edwards, he came up with something creative, which is, "Don't make me come up there and figure this out for you," if the people sit there too long and don't come up with something. I mean, he basically says, "Look, this is what I'm getting. If you can't figure it out, that's your problem. I'm going to come back to you once you figure it out." It's like, "Oh man, that is good."

[00:19:41] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Michael Shermer. We'll be right back.

[00:19:46] This episode is sponsored in part by Purple Mattress. As the world becomes increasingly uncomfortable, we're all looking for as much comfort as we can get. Now, this is a true story. I bumped into my friend at the airport. She was there with her uncle waiting with flowers and signs to meet his overseas girlfriend that he had met online. Long story short, she never showed up. He'd been sending her money and everything. It turns out she was just a con artist. That was an uncomfortable situation. But the one thing I can always count on is how comfortable my Purple Mattress is. And that's because Purple is comfort reinvented. Only Purple has the grid, which is a stretchy gel material. That's amazingly supportive for your back and legs while cushioning your shoulders, neck and hips. I don't know how it does it. It's just fantastic. It's a design, the grid doesn't trap any air. Air circulates around. So you'll never overheat. It bounces back. The grid does so you can move and shift unlike memory foam, which remembers everything, kind of like your ex. That's why memory foam has craters and divots kind of like your ex. You can't underestimate shady mail-order brides nor the cool side of the pillow. With the Purple Pillow, it always stays cool and refreshing on the cheek. I love how it supports only the parts that need this. Like how the unique grid technology cradles my ear instead of just smashing it. And right now you can try your Purple Mattress risk-free with free shipping and free returns. Financing is available too.

[00:21:02] Jen Harbinger: Purple really is comfort for an uncomfortable world. Right now, you'll get 10 percent off, any order of $200 or more. Go to purple.com/jordan10 and use promo code Jordan10. That's purple.com/jordan10 promo code Jordan10 for 10 percent off any order of $200 or more. Purple.com/jordan10 promo code Jordan10. Terms apply.

[00:21:20] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Better Help online counseling. Often people freak out when they hear the word therapy, but contrary to common misconception, therapy isn't just for those who are struggling with mental illness. It can be beneficial for anyone who's experiencing stress, intense emotion, life, transition, and wants to improve their life. That certainly sounds familiar to me. Talk therapy provides you with a safe, nonjudgmental place to vent about your experiences, explore your options, and develop the skills to handle various life challenges. If you've always wanted to try therapy, which I recommend, or you'd like to try it again, which of course I recommend. You just need to talk some things out. I understand that too. Better Help offers online licensed professional therapists who are trained to listen and help, not like your caring friend who's just going to hear you out. These are people with real skills that can help you gain some of those same skills to make it through whatever issues you're dealing with. Finding a therapist can be kind of a pain, not with Better Help. You fill out a questionnaire. They'll hook you up in a couple of days, everything obviously confidential and very convenient.

[00:22:20] Jen Harbinger: The Jordan Harbinger Show listeners get 10 percent off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan. Visit better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan and join over a million people who've taken charge of their mental health with the help of an experienced Better Health professional.

[00:22:33] Jordan Harbinger: Now back to Michael Shermer on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:22:38] People are looking for that confirmation. We've got confirmation bias, we've got different cognitive bias, and we have that deeply rooted human need for certainty that you write about in The Believing Brain where the brain is that belief engine and we look for things like patterns and try to find meaning in them. And I would love to discuss more of that as well. How our brain look for evidence to confirm conclusions or meaning in beliefs that we already have?

[00:23:01] Michael Shermer: Right. Well, this is true for our religious beliefs, political beliefs and so on. Just think about how the political system operates people on the right, for example, listen to Conservative Talk Radio, Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, Mark Levin, and so on. Or they watch Bill O'Reilly on Fox. They read the Wall Street Journal. Liberals, they read the New York Times. Every academic, liberal academic, they cite the New York Times like it's chapter and verse, like it's the Bible. Well, there's not a lot of liberal talk radio for sure but there are certain TV channels that are perhaps more liberal. And so what people are doing there is they're filtering the information in, and it's not that the information they're getting is necessarily factually wrong, they're only getting one side of it. And that's why we need a free press for sure. But of course, a free press means you're going to get slanted press in both directions.

[00:23:52] And that's true for religion as well. Whatever religion you are, of course, you're going to go to a church that supports that particular religion, which is going to be filled with people that think like you, believe what you believe, and can tell stories that confirm everything that we believe is true. And, you know, rarely does anybody like go to another church just to see what it's like in case they're wrong. They may go because a spouse or friend wants to go or something like that. Or maybe once out of curiosity to see, you know, what the Holy Rollers are like, or a Buddhist is like, something like that. But you wouldn't go regularly as a means of double-checking or retesting your hypothesis. Because political beliefs and religious beliefs are not considered by most people to be scientific hypotheses that we want to test to see, which is correct, they're more like moral beliefs. "I believe in rights or I believe in Liberty or I believe in whatever."

[00:24:45] It's not something that you want to be subject to, let's say, disconfirmation by new data. That very much drives most of our beliefs. This is why things like global warming it's politicized so much, that it has nothing to do with science. It has everything to do with, "Well, if it's real, that means those liberals are going to pass laws that hurt our economy and we're a pro-free market. And we don't want to hurt the economy. So it can't be true." The science is really secondary or tertiary at this point. And that's how most political and religious beliefs operate.

[00:25:16] Jordan Harbinger: And we see this even with smart people. In fact, in the book, in The Believing Brain, you talk about how smart people stick to beliefs even more because they're better at rationalizing those same beliefs.

[00:25:26] Michael Shermer: Yeah. Yeah, exactly. So if you're smart and educated, you know, you're good at pulling facts, you know, you're going to be even better at that than somebody who's perhaps less well-educated or intelligent. Really there are orthogonal, they're independent of each other. That is one's intelligence and one's beliefs. Other than the fact that it may make you better at being biased for your beliefs. But it's not like educated, smart people are less likely to believe nonsense. That's not at all the case, unfortunately.

[00:25:54] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like smart people believe weird things because they're better at rationalizing those beliefs that they've come to for non-smart reasons.

[00:26:03] Michael Shermer: That's exactly the way I said it. Yep. And it's good to remember that because we tend to think that it's those other people, those idiots that believe nonsense, not us, but of course everybody believes stuff that they can't really prove. It's just a belief, which is why it's problematic to say something like, "I believe in evolution." It's just something that happened. It's like saying, "I believe in gravity." Well, I hope so, but whether you believe it or not, it doesn't matter. You're still going to fall off buildings or plate tectonics or the germ theory of disease, you know, we don't think of those beliefs in the same way as say rights or democracy.

[00:26:37] But in a way, the point I'm making in The Moral Arc is that they are actually more overlapping than you think. We've arrived at democracies as a way of governing large populations because it works measurably better. And in a way, these are experiments. You can run the experiment between North Korea and South Korea, and you can see which one produces the higher GDP, taller people, better diets, more lights, fewer working hours, or more working hours per week, just all these measurable differences. And we've been running those experiments for centuries now. Even like things like gun control, you know, all 50 States have different laws about conceal and carry and assault weapons, and which pistols you can buy and how much ammo you can buy. These are all experiments.

[00:27:23] We can essentially look at the data. This is what criminologists do. Look at the data between States or between counties and see which one produces more or less homicides per capita, for example. Do we care that 30,000 plus people a year die from guns? Those are not all homicides. It's about the third homicides, the rest suicides and accidents. And are we willing to give up a certain amount of our gun freedoms in order to reduce the carnage? Well, I think we should, but as you tell, a lot of conservatives don't agree. They don't seem to care how many people die. It's really disconcerting to me and I'm not a standard liberal on this issue at all. I used to be against gun control. I just really looked into it and I really see it as kind of like an experiment. "Okay, do we agree we want to reduce the carnage?" Yes, of course.

[00:28:08] We were already doing this with automobile. Yes, it used to be in the 40,000 and 50,000 a year. Now, it's the low 30,000 a year dying automobiles. And once the, you know, self-driving cars are implemented, you know, there'll be a 10th of that. I'll be like maybe 3,000 a year dying automobiles. With seatbelts alone and other safety measures reduce the carnage. So we were willing to do that. We already do this in all walks of life, except for guns. Guns have been almost fetishized in our culture. They're almost like religious icons of some kind, almost like the American flag. You know, don't burn the American flag. Don't take away people's guns, but people are willing to go — well, seatbelts. Yeah, of course we should have seatbelts. Wait, doesn't that? Take your freedom away.

[00:28:51] Jordan Harbinger: Almost foresee the right to drive group, but the future being the next sort of NRA and the next 15, 20 years, "Hey, I have a right to drive my own car. I don't trust the machines." It'll be those guys that are saying I have a right to drive and they'll kill hundred times more people per year than self-driving cars around the world. And we'll have this whole constitutional issue. I mean, look, if you're listening to this 10, 15 years from now, tell me how close I am, because I won't remember it.

[00:29:15] But let's talk about how beliefs form, I mean, how does sensory data come into our brain and create beliefs? There's a whole process that's involved here that we, of course, don't realize is happening.

[00:29:27] Michael Shermer: It's all subconscious, of course. You know, data comes in through our senses and we begin to form patterns, find patterns. What we're really looking for is causality. That is really connected to being, we want to know for safety reasons, for reproductive reasons, for getting food reasons, whatever, just survival and flourishing reasons. So most of the beliefs we have, they're very basic, they're very similar. If I do X, will Y be the result? Well, that's just connecting A to B, so to speak, or I guess, in this case, X to Y. And, you know, that's classical conditioning, operant conditioning, you know, the basic stuff you learned in intro psych. Those are the most fundamental beliefs on which we build more and more. Most of this, again, happens subconsciously. You don't need to think about it and that's a good thing. It's a lot of information processing that doesn't need to be consciously processed. That's the sort of thing that happens without you really even thinking about it.

[00:30:17] And by the time the confirmation bias kicks in, you're also not aware of that. You're already pretty far down the road. So by the time you get to religious or say political religious beliefs, a lot of that's very much dependent on your family background, where you happen to be born and raised influences in school, teachers, mentors, books, things like that, all of it. It just sort of piles up over the course of a life without you much thinking about it, which is why students are kind of open to new ideas when they go to college. They're in between their parental family and building their own family. So they have fewer commitments, behavioral and cognitive, commitments to belief systems, you know, which is why college is good to teach lots of different ideas and topics, which is why open debate is so important. Which is why I'm concerned about the recent downturn against free speech on college campuses, in the name of hate speech, to protect students from bad ideas to make the campus safe from bad ideas. Well, who decides what's the bad idea? Who decides what's hate speech?

[00:31:21] I'm very concerned about that because students really need to be exposed. That's a critical time to lots of different ideas, not just the ideas that the official dogma of the academy says is okay. If you're on one side, you really better read and watch what the other side is watching and reading. If you want to understand what they're thinking and get past a bunch of immoral idiots because that's not particularly helpful. I mean, it's not likely that half the country is stupid and evil, even though that's what each half thinks about the other is not true. So what is it they're thinking? Well, the only way to find out is to read what they read and what they watch. And it's very enlightening.

[00:31:59] I really encourage my students to listen to Rush Limbaugh or watch Bill O'Reilly and it's a real eye-opener. It's like, "Wow. I mean, people actually believe." Yeah, they do. They listen. They watch. They cite it. They believe it.

[00:32:10] Jordan Harbinger: So we've got sensory data flowing through our senses. As you write in the book, the brain looks for patterns and then infuses those patterns with meaning. And you write that our brains connect the dots of our world into meaningful patterns that explain why things happen and these patterns become beliefs. Can we flesh that out a little bit? I mean, how does our brain start to look for and find confirmatory evidence in support of our beliefs? I would imagine it reinforces the beliefs and becomes a cycle that you can't really break very easily.

[00:32:38] Michael Shermer: Well, just another classic experiment in this. If you tell somebody that the new person you're about to meet is extroverted amongst other traits that you use to describe them, and then they meet them. They're more likely to describe the person as extroverted. If you tell another subject that the same person is introverted, they'll describe them as introverted. Now, the person is just neutral. They're not doing anything. They're not leaning one way or the other introversion or extroversion. These are subjects that work with experimenter. The idea is that you're looking at somebody talking to somebody and you're only going to notice certain features or things that they do or say that seemed to fit the extroversion mode or the introversion though that you have in your mind.

[00:33:22] Now, that's kind of a simple example of a more complex process that you can see, for example, in another study that was done in which a healthcare reform bill was given to either self-reporting Democrats or self-reported Republicans. And if the self-reported Democrats are reading a healthcare reform bill, that they're told was written by a Democrat, they'll praise it. They'll like it. They'll find few errors. But if you tell them it was written by a Republican, they'll rip it to shreds. They won't like it very much. They'll find the flaws and errors in it. And so on and vice versa, you know, if it's a self-described Republicans and you tell them the report was written by Democrats, they'll rip it to shreds and so forth. If you tell them it's written by one of their fellow tribe members and they'll like it. And everybody's reading the same words. So, what they're doing is still throwing out the words that they don't like and looking for the words that confirm what they already believe. So, you know, some more examples of the motivated reasoning. It's a very, very powerful effect. It's come to light in the last couple of decades that this is probably the mother of all cognitive biases.

[00:34:24] Jordan Harbinger: In the book, the crux of which is that we believe first and then seek confirmation for our beliefs later. It seems like you're saying that, yeah, confirmation bias — look, cherry picking, employing other common biases, things like that. The antidote for this, as you argue, is science. And I would love to start to teach the audience how to use a little bit of science and critical thinking to get past some of the crazy things that we believe. It seems like in our human quest to make sense of the world, we've kind of got a double-edged sword here with our brains and the way they work.

[00:34:55] Michael Shermer: Yeah, absolutely. So getting back to the free speech thing, what's underneath that is just being exposed to other beliefs. The way it kind of works more subtly in science is just how the system is set up, where even though you're running experiments to see if the claim is true or not, and experiments are blind and double-blind to avoid those biases. And when you're working in a light, you start off as an undergraduate, then a graduate student, you're working in somebody's lab and the protocols already set up. These are the experiments we're running here. You're a first-year graduate student, you know, what do you know? You're just running the experiment. You're just carrying through the step-by-step process that the lab runs. And so you're kind of just sucked into it. You know, it takes a while to pull back and look at the bigger picture and go, "Well, what is it we're actually testing in? Have we thought about other variables that we should be including in the experiments to see if those are the effects that we should be looking for?"

[00:35:50] And it's hard to see that until much later, maybe when you're actually a professor and you open your own lab and you start to branch out or push out a little bit. So science is pretty conservative in that way. Most scientists are not too anxious to find counterexamples to their experiments. And the experiments are designed in a way to restrict those because you have to restrict the number of variables you're measuring in order to determine which one is really the cause. But in so doing, you might be missing something completely different that you're not even thinking about it.

[00:36:20] Jordan Harbinger: Right. So in our quest to know, we also kind of want to believe, so we're constantly on that scale, trying to make a balance, even if we're scientists.

[00:36:29] Michael Shermer: Yes, exactly. I mean, it's rare that, you know, scientists are just collecting data with no hypothesis to test in mind. I mean, there's a few of these, you know, like astronomical studies where they're just measuring 10,000 different stars just to see how to catalog them. That's the kind of thing that's pretty rare. Usually, you know, if you're writing up an experiment, you have to have a hypothesis that you're testing. Why are we collecting this data? Are we going to compare this to that? You have to have something to test or else you're not really doing science. So you're not going to get published. But in, so doing, you're not thinking about what else might be going on, something completely different, which is why I think there is occasionally a role for an outsider to come in, but think completely differently. Although I don't want to push that too far because all the alternative theories of physics people come in from out of nowhere, they're almost always wrong. They don't even know how to play the game, but they think that all the mainstream people are too narrow minded. You know, my only point is that science is flawed to a certain extent, but it is still the best system we have.

[00:37:32] Jordan Harbinger: This doesn't just apply to scientists and scientific research. This applies to regular people too. I mean, beliefs can be as simple as superstitions, which as you wrote in the book, even pigeons are superstitious as per some of the experiments that you run, which I think is kind of amazing. Can you discuss superstition and how this fit into the belief system and how our brains?

[00:37:53] Michael Shermer: Yeah. We tend to think of superstitions as something flawed in the brain, but my point of going through those experiments to show that, in fact, it's just how the brain is wired to connect A to B, because usually if there is a knock or a sound or something, a rustle in the grass, there is a chance it could be a dangerous predator and not just the wind. And so it behooves the organism to assume that all rustles in the grass are dangerous predators just in case. Now, that's not always the case. You see these Fur, Fin, & Feather Show on the nature channels, you'll see most of these animals are pretty skittish. They're pretty risk averse, ready to jump at any moment, but not a hundred percent, but you know, they're not in a constant state of flee. They're at the waterhole. They're very cautiously looking around, listening, and maybe they'll see a lion in the distance sleeping, but they'll kind of keep an eye on it. So they don't run at every little rustle in the grass.

[00:38:45] But my point is that assuming that it's possible that the rustle in the grass is a dangerous predator, is what we call superstition when it turns out it's not. And really all that is, is a type one error that is a false positive. You thought A was connected to B, and it's not. You know, that's a harmless error to make, but the other one is costly. That is you don't assume the rustle in the grass is a dangerous predator and it turns out it is. That's more likely to take you out of the gene pool. I'm claiming that we evolve this propensity, our brains evolve is propensity to assume that As are connected Bs, even when they're not. And we don't have a good filtering system because there was no science when we evolve.

[00:39:25] Jordan Harbinger: Even if there was, it's not like you can't reproduce, if your beliefs are faulty.

[00:39:29] Michael Shermer: That's right. I mean, people that believe in astrology have no problem making babies.

[00:39:33] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:39:33] Michael Shermer: No plumbing system works just fine, so that regardless of your crazy beliefs. But you know, so why can't the organisms sit in the grass and collect more data about the rustle in the grass, whether it's a dangerous predator or it's just the wind? And the answer is because dangerous predators don't wait around for organisms to collect more data about them and decide what's true or not. You have to make a snap decision, which is why research and cognitive psychology and rapid cognition, that is most of the decisions we make in life are done intuitively, rapidly, without much deliberation.

[00:40:06] So that's why Daniel Kahneman, title of his book, Thinking Fast and Slow. The thinking fast is how we initially make most of our decisions. Thinking slow is where we deliberate over it. It's like shopping for a house. You kind of try to go through and make a list of all the characteristics you want, but usually it comes down to the short list of just how you feel. "I don't know. I just liked this. I don't know why." And that turns out to be true, how we shop for toothpaste or whatever. "I don't know. I like the blue one." You know, there's not necessarily a lot of rationality behind it. And motions evolve to direct behavior because we don't have the time to process information like a computer would and weigh in the balance, every single characteristic of the toothpaste or the house or the spouse or whatever.

[00:40:50] And that's a good thing we know from the studies of people that have brain damage to the emotional areas of the brain, where they just become like Mr. Spot. Everything is a complete rational calculation. You're going to carefully consider every aspect before they make a decision. These people can barely get out of the house in the morning, even go on their daily chores. They can't get anything done. They can't make decisions. They sit there in the aisle of the toothpaste section going, "I don't know, you know, there's 200 choices. I don't know. There's just too many options to consider." And that's why it's good to often just say, "I like the blue one."

[00:41:25] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Michael Shermer. We'll be right back.

[00:41:30] This episode is sponsored in part by Blue Nile. At bluenile.com, you can celebrate all of life's special moments from creating the custom engagement ring of her dreams to gifting a once in a lifetime piece, all at prices you won't find at a traditional jeweler. When I was looking for a ring for Jen, I was obviously overwhelmed by the myriad of options available. I was also feeling leery about buying a diamond online without seeing it in person first. Not that I could tell anything about diamonds, but you know, felt weird about buying something that big online. It's a big decision. We don't want to make the wrong choice. Not the perfect piece, no problem. Blue Nile offers peace of mind with a hundred percent satisfaction guarantee. Shop stress-free with guaranteed free shipping and returns with a 30- day return policy. And if you're in the doghouse, you need something special and you need it fast, they can deliver overnight. They'll put it in a discreet package that won't give away what's inside.

[00:42:16] Jen Harbinger: Make the moment sparkle with jewelry from bluenile.com. The Jordan Harbinger Show listeners get $50 off $500. This podcast exclusive offer includes engagement. Use code Jordan, that's code Jordan. Plus every order is insured, ships free, and arrives in discreet packaging that won't give away what's inside. Shop stress-free and find your forever peace, go to bluenile.com today.

[00:42:37] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by LifeLock. Cybercriminals are taking advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic and I mean, everything else for that matter. They scam people, stealing their money, personal information. They attempt to exploit people's hardship due to a loss of a job or reduced hours with phishing emails and fake websites. I just got a freaking medical scam thing that was like a vaccine scam. I mean, these guys are shameless. It's important to understand how cybercrime and identity theft are affecting our lives. Every day, we put our information at risk on the Internet. In an instant, a cybercriminal can harm what's yours, your finances, your credit, your reputation. That's why I use LifeLock. It's one of the reasons anyway. LifeLock helps detect a wide range of identity threats, like your social security number for sale on the dark web. One thing that I have found as well. If they detect your info has been potentially compromised, they'll send you an alert. They'll also help you fix it if you really get into muck.

[00:43:27] Jen Harbinger: No one can prevent all identity theft or monitor all transactions at all businesses. But you can keep what's yours with LifeLock Identity Theft Protection. Join now and save up to 25 percent off your first year at lifelock.com/jordan. That's lifelock.com/jordan for 25 percent off.

[00:43:43] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored in part by NetSuite. If you're a business owner, you might be making, running your business harder on yourself than necessary. Don't let QuickBooks and spreadsheets slow you down anymore. It's time to upgrade to NetSuite, stop paying for multiple systems that don't give you the info you need when you need it. All those spreadsheets, all that software you've outgrown. NetSuite by Oracle, it's like a dashboard for all of your financials, HR, inventory, e-commerce everything all-in-one place. It works on the phone. I'm a huge fan of this because the founder is super sharp dude. This software has made a lot of my entrepreneurial friends' lives easier. So whether you're doing a million or hundreds of millions in revenue, save time, save money, make sure you got everything right in front of you with NetSuite. Over 24,000 companies are using NetSuite right now at least to give it a shot and check it out.

[00:44:31] Jen Harbinger: Let NetSuite show you how they'll benefit your business with a free product tour at netsuite.com/jordan. Schedule your free product tour right now at netsuite.com/jordan netsuite.com/jordan.

[00:44:44] Jordan Harbinger: Thanks so much for listening to and supporting the show. Your support of advertisers is what keeps us going. And I really appreciate when you'd use the links. I know a lot of you buy a lot of stuff from sponsors and you say, "Oh, I didn't use the link. I didn't think you would care." They track that stuff. I wish we didn't have to, but them's the breaks. All of the discounts with all the codes, everything it's all on one page, we made a page for you at jordanharbinger.com/deals. Please do consider supporting those who support us. And don't forget, we've got worksheets for today's episode if you want some of the drills, exercises, takeaways that we talked about here during the show. They're all in one easy place. And that link is in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast.

[00:45:23] Now, for the conclusion of our episode with Michael Shermer.

[00:45:28] This program sitting somewhere in our lizard brain, our primitive brain, hanging out, and then as humans as evolved social creatures, we've got this entirely different set of calculations going on, and this programming creeps its way in there. So we attach social meaning to patterns as well. How does this start to affect our behavior?

[00:45:48] Michael Shermer: Well, we're social primates. Often, all this stuff we're talking about, motivated reasoning in general, sorts itself out in its moral tribes or groups that think alike morally that have similar foundational values of what they think is the most important thing in life. And here's where it starts to get dangerous. Here's where we can talk about terrorism and why people join these groups. I mean, who in their right mind would join ISIS. They're insane. Well, because they're in a state of mind where they want to belong to a moral tribe. They want to feel like they have meaning and purpose and something deeper. That feels emotionally good. Again, that emotional component.

[00:46:27] You know, we know about the research from behavioral genetics that people are, that are highly genetically inclined to be either conservative or liberal or religious or not very religious. Well, there can't be a gene for being a Catholic or a Democrat. No. What it is its genes code for personality temperament. Like, I like this kind of worldview because it makes me feel good. And all these other people that are in this group, this tribe, they're like me and I like being around people that are like me. It feels good. And that's where the genes and the emotions kind of meld there. And it ends up being that, well, we call our moral drive Democrats or Republicans or Catholics or Protestants or Buddhists. And the culture ends up sorting it out in the details but the deeper part is how we feel about being a part of that group. And we kind of migrate to it.

[00:47:20] Kind of explanation for these, some of these bizarre twins' studies where, you know, the people that are separated at birth and they show up as adults and they have the same clothing on, or they drive the same kind of car, they married the same kind of person, or they use the same toothpaste. I mean, there's so bizarre. It's like there can't be a gene for buying a Mustang or, you know, marrying this kind of person — well, in a way there is in the sense that I like the way I look in these kinds of clothes because it makes me feel better. And your twin is going to have those same feelings because their emotions and feelings are very much genetically programmed. So they're going to end up more likely to buy that same kind of car, dress the same way, marry the same kind of person and so on. And it looks kind of bizarre, but all of that scales up to these kinds of bigger political, moral religious groups that we belong to.

[00:48:07] Jordan Harbinger: So you can see these commonalities in genes and in tests of genetic structure and also even in brain behavior. For example, you wrote that we get a rewarding jolt of dopamine when we come across information that confirms what we already believe. So, I mean, this might be a stretch, but are we addicted to confirming our beliefs?

[00:48:25] Michael Shermer: Absolutely, of course, it feels good to have your beliefs confirmed. "I knew I was right. I knew it. I knew it." That's a great feeling and that is dopamine. We know that dopamine is involved in learning and motivation and, you know, neurons that secrete dopamine. It's part of the process of growing these synaptic connections when you learn something. That somewhere in the brain that gets recorded as feeling good, whatever that means, qualitatively to each of us, but we know it's related to dopamine. So it just comes down to that kind of genetically wired biochemistry in the brain. And it's hard to believe that that can affect such social, cultural kinds of things, but it certainly does. This isn't genetic determinism by any means. Culture still plays a huge role, but trying to understand why somebody would be a self-radicalizing terrorist, you know, we really need to get down to looking at all those different factors.

[00:49:16] Jordan Harbinger: Well, it makes sense, right? Because you discuss belief dependent realism and that reality exists independent of human minds but our understanding of it depends on the beliefs we hold at any given time. So that sort of explains, at least in my opinion, of my understanding, my reality, how different political groups or different religious groups can look at the world so differently along with the biases, like anchoring bias, authority bias, belief bias, and the previously discussed confirmation bias. But on top of all of those biases we have in group bias, which just reinforces the same bias that you got by joining the group in the first place.

[00:49:51] Michael Shermer: Yeah, exactly right. So it does make me wonder, now that I'm a little older looking back at what was popular saying. My field of experimental psychology in the '70s, or if you look back a century before, but scientists were studying then and it's not that they were wrong so much as the science just seems to move on to other topics. We know that Skinner's research on rats and pigeons with operant classical conditioning, you know, it's pretty solid science, but it just didn't seem to go very far. It didn't take us very far in understanding human behavior, which is why the cognitive revolution happened in the '80s, primarily in the '80s and '90s. Now it's really cognitive neuroscience. It's a huge thing.

[00:50:34] And it's not that the previous scientists were wrong. So much is just limited. So it makes me wonder. What the stuff we're doing now, cutting edge stuff now? A century from now, people look back and go, "Huh? It was really weird they went down that tangent of cognitive neuroscience or behavior genetics." Whatever it is. I don't know. If I knew I wouldn't be doing it. I'd be critical of it, but I don't know what it is. And, you know, that's probably all we have. You know, it's like when I think about what I'm going to write in my next column in Scientific American, every month I got to come up with something. What should we be skeptical of? And sometimes it's really hard to tell.

[00:51:07] You know, if we've already sort of jumped the shark and everybody knows X's idiotic belief — that's an easy target for me. But more challenging is I try to find stuff that hasn't already been debunked, that not everybody thinks is obviously wrong. And that's really hard to do because if I knew I would already know. It would be obvious.

[00:51:24] Jordan Harbinger: So we start with our genes, our programming, our evolved programming. We develop a bunch of beliefs. They get processed through a lot of these different biases. Then we end up joining a group, getting in-group bias, and then to top it all off, we've got this meta bias. This belief dependent realism is driven by this meta bias called the bias blind spot. And as you wrote, "The tendency to recognize the power of cognitive biases and other people, but to be blind to their influence on our own belief." In other words, bias against your own bias where you can't see it.

[00:51:54] Michael Shermer: Yeah. Those experiments are quite interesting. Even when you tell subjects about the confirmation bias, they become very adept at seeing how it works in other people, but then you go, "Well, you know, it could apply to you." "Well, not me. Of course, I'm not like that." It's almost impossible to see it in yourself, very, very difficult.

[00:52:11] Jordan Harbinger: I mean, with all of this stacked against us, do we stand a freaking chance of ever seeing anything as it is?

[00:52:16] Michael Shermer: I think so. I think the systems do shift over time on a higher level. That is the science does move along as I mentioned earlier, but on a separate related question: how do we get people to recognize it and change their minds? Like, "You know, you're really wrong about climate. You know, you don't think global warming is real. You're wrong. And here's why—" Just showing people that they're factually wrong is not necessarily the best strategy because we know that people, if they just don't accept it well, but Rush was saying that that study was bought. So, you know, short of like taking out the papers and going through those studies one by one, which you can do, but that takes a while. Another approach is to go tribal and just say — or go more psychological and say, "Look, the scientific researcher is not going to take anything away from your worldview. It's not a challenge to your moral tribe. It's not a threat to your religion, to your economic political ideologies. You try to remove that barrier, which is what's there in the first place. That's keeping them from evaluating the data properly or the way most scientists evaluated.

[00:53:16] And in other words, that's cognitive dissonance. That is, if somebody holds a belief and you show them evidence that it's wrong, they don't change their mind. They double down on the belief. You know, the famous experiment that happened with UFO cults. Back in 1954, Leon Festinger went to the top of a mountain with a UFO group to see what would happen when the mothership didn't come at midnight. And basically, his book, When Prophecy Fails, was about what happened. They doubled down on their belief and they had all sorts of rationalizations for why it didn't happen or even that it did happen. Spiritually, the world changed through some such thing.

[00:53:50] When it gets down to convincing somebody that creationism is wrong and evolutions right or global warming is real or whatever, you know, you can't just start with the facts because the facts don't speak for themselves. They're just not going to believe it. You have to start with something like, you know, it's not a threat to your foundational beliefs and then go from there.

[00:54:09] Jordan Harbinger: So, is there anything else that I haven't asked you that you want to make sure you deliver to the audience?

[00:54:14] Michael Shermer: The important thing is that we now have a viable movement with a lot of resources at our hands to provide to people, which is what we do at Skeptic, so skeptic.com, tell people to go. There's tons of free material on it. We have a whole skepticism one-on-one section. I teach a course at Chapman University called Skepticism 101, basically how to think like a scientist. And there's all these examples we're talking about. They're all there and videos and articles and PowerPoint presentations. And so if you're a teacher and educator, if you're just interested, skeptic.com, how to talk to people about global warming, how to talk to people about evolution and creationism. We have booklets and articles about that, you know, point by point, here's what to do and here's what to say. I think that's where we are now in the movement. We really have a pretty good handle on what to do about these issues and what we know and what we don't know.

[00:55:03] Jordan Harbinger: Great. Thanks so much, Michael. Really interesting, the evolution of belief and how it still affects us today, even when we think it only affects other people. I really appreciate it.

[00:55:12] Michael Shermer: You're welcome.

[00:55:15] Jordan Harbinger: I've got some thoughts on this episode, but before I get into that, we were humbled to have the opportunity to talk to the late Kobe Bryant for this interview, just a few short months before the tragedy. Here's a preview with one of basketball's most iconic legends, Kobe Bryant.

[00:55:29] Kobe Bryant: I love the game. I love it. I didn't want to be away from it. I wanted to play all the time. I was 18, 21 years old. I wanted to play basketball. I was consumed with this quest of trying to be the best. I knew I wanted to win five, six, seven championships. For me, to come out and say that people would think I was a lunatic.

[00:55:50] Negotiate with yourself. Know what happens inside of here. Are you able to negotiate your way out of that little voice telling you it's not that important or does that little voice get the best of you? Remove the ego from this process. Just focus on the act. And when you do that, now you can look at actions and then you can truly improve. How can you lock in and get into that mental space where nothing else matters? The noise of the crowd doesn't matter, whether they're cheering or booing. It doesn't matter. You're just completely locked in. How do you do that?

[00:56:21] Jordan Harbinger: How do you not let demons of uncertainty get inside your head? Like when you tore your Achilles, are you not thinking like, "Oh-oh, how am I going to come back?"

[00:56:28] Kobe Bryant: Oh God yeah. If you're nervous or scared about a situation instead of being like, "Nah, there's nothing to be scared about, nothing to be scared about. Oh shit! There is." And that's fine. That's okay, you know, like you own it, you give it a hug, embrace it. And now what are you going to do about it?

[00:56:43] Jordan Harbinger: For more with Kobe Bryant, including how Kobe managed pressure in high stakes situations and lessons Kobe learned from the people who are the best at what they do, check out episode 249 on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:56:57] Man, I just love diving into the science of belief, why we believe weird things, patternicity. This is right up my alley. I hope you enjoyed this one. It's from the vault. I've looked at some of our old episodes that I recorded three, four, five, 10 years ago. Most of the ones that are really old are kind of crap, but there's a gem here and there. And I'm glad to tell you that we're going to be putting a lot of those back in the feed. So if you've been listening to us for eight-plus years, you might hear something that you vaguely think is familiar, although I assume you forgot everything by then because I know I sure did. But it's kind of funny to hear myself interview somebody from years ago. And I think what missed opportunities and also I sound very punch-able and I just kind of — it's a little cringe, but you know, the things I do for you.

[00:57:35] Thanks to Michael Shermer. Links to all his stuff will be in the website in the show notes. Please use our website links if you buy any books or anything from any guest on the show. That does help support the show. Worksheets for the episode in the show notes. Transcripts in the show notes. I'm at @JordanHarbinger on both Twitter and Instagram. You can always connect with me on LinkedIn as well. I always love hearing from you there.

[00:57:55] I'm teaching you how to connect with great people and manage relationships, using systems and tiny habits and a little bit of software that we created for you. That's over at the Six Minute Networking course. That course is free. It's over at @JordanHarbinger.com/course. I'm teaching you how to dig the well before you get thirsty and build relationships before you need them. Most of the guests on the show, they subscribe to the course. They contribute to the course. Come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong.

[00:58:21] This show is created in association with PodcastOne. My team is Jen Harbinger, Jase Sanderson, Robert Fogarty, Millie Ocampo, Ian Baird, Josh Ballard, and Gabriel Mizrahi. Remember, we rise by lifting others. The fee for the show is that you share it with friends when you find something useful or interesting. If you know somebody who's interested in the science of belief, how we believe things, why we believe things, why we can't admit that we're wrong when we believe things, definitely share this episode with them. I hope you find something great/interesting in every episode of this show. I work really hard to pull that out of the guests. Please do share the show with those who care about. In the meantime, do your best to apply what you hear on the show, so you can live what you listen, and we'll see you next time.

[00:59:06] Jayson Waller: Jayson Waller here, host of your True Underdog podcast and YouTube channel. This is what you've got in store in our episodes. I'm going to tell stories of me growing up, being in trailer park, high school dropout, teen dad, to opening three businesses that were successful. The latest business winning Inc 500, three out of four years, entrepreneur of the year and it's a billion-dollar company. That's right. I'm going to give you tips, strategies, how to overcome adversity, how to be better, how to not stay in the mud. On top of that, on this show on the full episodes, we're going to have interviews with people who have overcome adversity, people that have been successful, but started with things in their way, things they had to overcome and struggle with. How did they get there? Check us out on iHeartRadio, Spotify, or Apple Podcasts. You can go to trueunderdog.com. Subscribe to everything, or go to YouTube at the True Underdog podcast.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.