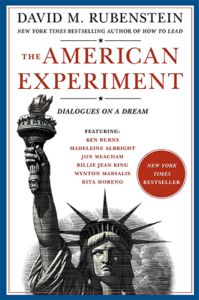

David M. Rubenstein is co-founder and co-executive chairman of The Carlyle Group, host of The David Rubenstein Show, and author of How to Lead: Wisdom from the World’s Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game Changers and The American Experiment: Dialogues on a Dream.

What We Discuss with David Rubenstein:

- Why David was one of the original signers of The Giving Pledge, a promise to give away the majority of his wealth instead of just building a stockpile of money for his heirs.

- The many ways David gives back to the United States for the privilege of growing up here, but why he eschews the idea of running for office.

- Why David finds giving away his money more rewarding than making it.

- The key errors people commonly make when fundraising for their business (and what they should be doing instead).

- How David raised his kids to develop the skills and strong work ethic to succeed without spoiling them.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

On this episode, David joins us to discuss why he signed The Giving Pledge (effectively promising to give away the majority of his wealth instead of letting subsequent generations of his family hoard it), why he feels like acts of patriotic philanthropy are of greater service to society than an ego-driven run for office, why it’s really better to give than receive, common fundraising errors and their solutions, how he raised kids to become upstanding adults without spoiling them along the way, and much more. Listen, learn, and enjoy as we approach the new year ahead together!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

This Episode Is Sponsored By:

- Lendtable: Go to lendtable.com and use promo code HARBINGER to add an extra $50 to your Lendtable balance

- Magic Spoon: Go to magicspoon.com/jordan to grab a variety pack, and use code JORDAN at checkout for $5 off

- BetterHelp: Get 10% off your first month at betterhelp.com/jordan

- Credit Karma: Go to creditkarma.com/loanoffers to find out more

Miss our interview with Freeway Rick Ross, the crack empire kingpin gone good? Catch up with episode 121: Freeway Rick Ross | Life in the Crack Lane here!

Thanks, David Rubenstein!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- The American Experiment: Dialogues on a Dream by David M. Rubenstein | Amazon

- How to Lead: Wisdom from the World’s Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game Changers by David M. Rubenstein | Amazon

- The American Story: Conversations with Master Historians by David M. Rubenstein | Amazon

- The David Rubenstein Show: Peer-to-Peer Conversations | Bloomberg

- The Carlyle Group

- The Giving Pledge

- Was Jimmy Carter the Most Underrated President in History? | The New York Times

- Blow Up the Donor-to-Ambassador Pipeline | The New Republic

- How to Overcome Imposter Syndrome | Deep Dive | Jordan Harbinger

- What Is Cognitive Dissonance? | Verywell Mind

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid | Prime Video

- Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting by William Goldman | Amazon

- With One Line, William Goldman Taught Hollywood Everything It Knows | Variety

- Jefferson Memorial Gets $10 Million For New Museum From David Rubenstein | NPR

- Opinion: I Funded the Rehabilitation of This Robert E. Lee Memorial. Congress, Please Rename It. by David Rubenstein | The Washington Post

- Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) | Investopedia

- The Carlyle | NYC

- David M. Rubenstein Discusses Entrepreneurship and Philanthropy at Harvard Law School | HALB

- Ray Dalio | The Changing World Order | Jordan Harbinger

- The Gates Foundation

- The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race by Walter Isaacson | Amazon

- Larry King Never Prepared For Interviews. Here’s Why | The List

- Jerry Seinfeld Rips Larry King | YouTube

- The Rise of Trash TV: Jerry Springer | SBS Viceland

- Scott Galloway | From Crisis to Opportunity Post Corona | Jordan Harbinger

- What It Takes: Lessons in the Pursuit of Excellence by Stephen A. Schwarzman | Amazon

- Stephen Schwarzman | Lessons in the Pursuit of Excellence | Jordan Harbinger

- Eleanor Roosevelt Opposed Women Getting the Right to Vote | the New York Post

606: David Rubenstein | Patriotic Philanthropy and Leading Large

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:02] David Rubenstein: The people that have made money by and large, with some exceptions obviously, are people that want to prove their idea work and it got successful and it took off. But it wasn't because they said, "I've got to make a billion dollars because I want to be rich. I want to buy a big house and so forth." Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Steve Jobs, all those people, they were not obsessed with making a large amount of money. They were assessed with building a company that had really good products and services. And that's what you really have to do if you want to make a lot of money. Don't worry about the money. If you build something good, the money will come.

[00:00:31] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We have in-depth conversations with people at the top of their game, spies, psychologists, astronauts, and entrepreneurs, even the occasional journalist turned poker champion, billionaire investor, or mafia enforcer. And each episode turns our guests' wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better critical thinker.

[00:01:02] If you're new to the show, or you want to tell your friends about the show — and I always love it when you do that — we have episode starter packs that should make that a little bit easier. These are collections of your favorite episodes, organized by popular topics to help new listeners get a taste of everything we do here on this show. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start to get started or to help somebody else get started.

[00:01:25] Now, today, David Rubenstein, co-founder and co-executive chairman of The Carlyle Group, a global investment firm with $230 billion under management. David is one of the original signers of the giving pledge, pledging to give away the majority of his wealth, instead of simply creating another singular family dynasty. He's also a fellow podcaster with a great roster of guests in his own right. Today patriotism, philanthropy, and politics, and why he will put his money where his mouth is, but never run for office himself. And why giving money away has been more rewarding than making it in the first place, which to be honest, I think is easy for him to say, but we'll get into that. Also fundraising for a business or company, and some of the key errors people make when it comes to this. And finally raising successful kids, especially when you yourself are making enough for them to never work and never worry about money, how to instill work ethic and skills in the next generation, of course, lots more.

[00:02:19] If you're wondering how I managed to book folks like this, it's because of my network. I'm telling you I have created something here that you can also create with a little bit of effort, six minutes a day. I'm teaching you how to do this for free at jordanharbinger.com/course. I don't need your payment info, no credit card info, nothing. It's just a free course. I know, surprising, right? Go to jordanharbinger.com/course. You'll find it there. And most of the guests, by the way, they subscribe to the course. They're in there contributing. So come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong.

[00:02:48] Now, here's David Rubenstein.

[00:02:53] So you trained as a lawyer. And you know, we have that in common. I did not work for Jimmy Carter, but he was the president when I was born. Just to sort of highlight the difference here. I know you stay out of politics and I've heard that you don't donate any money to politicians. Why is that?

[00:03:10] David Rubenstein: For a number of reasons for a long time, I've been the chairman of the Kennedy Center. I was chairman of the Smithsonian. I'm chairman of the board of the Library of Congress. I'm a member of the National Gallery of Art Board. And I've thought that if I were to do that, give money to politicians, it would diminish my ability to work with Democrats and Republicans on a bipartisan basis on those boards.

[00:03:31] Secondly, I don't like the perception that the press has of wealthy people who give money, that they're trying to buy something. And I don't want to be seen as trying to buy something. And so if I were to give a half a million dollars to some candidate, all of a sudden it'll say, "Rubenstein is trying to buy an embassy or trying to influence this. And I just don't like the perception that I'm trying to buy something from government.

[00:03:52] Third, there's no benefit to doing it, I can see, other than you're trying to buy an embassy or something like that. I just don't see any real benefit to it. There are plenty of other people who want to give money. I just like to stay out of politics at this point. I did that when I was younger. And now I'm trying to do something different.

[00:04:07] Jordan Harbinger: You say buy an embassy, I think a lot of people don't know that a lot of diplomatic positions, especially sort of paradoxically in countries like France, where you might have a career diplomat at the top-top, but the ambassador, which is almost in some countries, almost like a figurehead position often goes to donors. Am I getting that right?

[00:04:26] David Rubenstein: I think over the last 50 years or so, it's been very clear that about a third of the embassies go to people who are politically connected or people that are not career people. Two thirds go to career people, FSO, foreign service officers. But clearly that the most desirable places, France or England, or you know, Japan or China, those places typically go to people who are not career foreign service officers. And I am not interested in being an ambassador. And I have not ever talked to anybody about doing that. It's not appealing to me.

[00:04:56] Jordan Harbinger: It's interesting because you're the chairman on multiple boards, you'd think, well, naturally, you should be an ambassador. I mean, you've got a lot of leadership experience. You've got a lot of experience dealing with both sides of the aisle. I mean, it's well suited to you. I mean, obviously you don't think so, or you're just busy with other things.

[00:05:13] David Rubenstein: Oh, many times people get to be my age. I'm now 71, an age I never thought I'd live to be at, but when you're 71, many people are slowing down and they are looking to cap their career perhaps with an embassy, which has a lot of prestige to it. You're representing the United States. But I learned when I worked in the White House many years ago, that ambassadors really are just doing what young people at the State Department more or less tell them to do. They don't really have a lot of say. In the old days before instant communications, you had ambassadors who could really be that representative to you in France or England, but with instant communications, that's not necessary anymore. So it's almost as — Felix Rohatyn once said when he was ambassador to France, it's like being a concierge. You're basically wining and dining people that come in from your country and you're doing all the kinds of things and arrangements, and you don't really have a lot of political power and you're not really making policy. In addition, I'm not slowing down and looking to cap my career. I have a lot of things I'm still doing. So I wouldn't want to give up everything I'm doing to just go to a country and probably not have any impact on the policy. That's my theory.

[00:06:13] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, you're right. You'd probably be trading all of your board positions and all of these interesting initiatives that you're doing and running to sit around at dinner parties night after night after night hobnobbing with people that probably, I mean a good percentage of them, you won't be able to stand and won't want to talk to you at all for more than five minutes.

[00:06:33] David Rubenstein: Well, I won't comment on that. I would just say that I am trying to lose weight and when you get to be my age, it's harder. So if you've got a lot of embassy dinners, you're probably not going to lose weight.

[00:06:41] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that definitely makes sense. You said you'd never thought you'd lived at 71. Are you kidding about that? Or were you living a fast life earlier?

[00:06:48] David Rubenstein: No, I always lived a slow life, but you know, 23 percent of the people who were born when I was born in 1949 are deceased. So when I was growing up, my parents used to read the obituaries every day. And I say, "Why are you doing that?" "Well," they said, "they want to see who died." At a young age, I didn't care about that. Now, I read the obituaries every day because I want to see why somebody younger than me died or how they died and what happened to them. And you have to recognize as you get older that, you know, inevitably you're going to slow down or inevitably you're not going to live forever. I do think about it. And as you get older, you're too young to think about it. You do think about what you want to leave behind as your legacy. And you do think about what you want to get done before it's too late to do anything else.

[00:07:27] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Maybe I'll cap mine — now you got me thinking, maybe I should be a diplomat. I'm not qualified for the board of anything, but I'm good at eating.

[00:07:33] David Rubenstein: Well, you're probably pretty good at exercising. You're very slim. It looks like. So I don't want to denigrate being an ambassador. I think it's an important role. It's just not, I have no interest in doing it and no president's ever called me up and said, "You really should be ambassador to here and there." Now, people that go to be ambassadors, who are the one-third, they generally don't sit at home and people call them up and say, "You know, I'm the President of the United States, I really want you to do this." That happens rarely. Usually, you say I did something for the president. I did something for his campaign. I'd like something, this is what I want. And then you negotiate with the State Department of the White House on what's appropriate for you in the country. And I'm just not interested in that. So I don't denigrate anybody that wants to do it. I think it's a great thing to serve your country. I just think I'm doing things that are better for me right now.

[00:08:16] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that makes sense. The highest I got in the State Department was working at the embassy in Panama, and we didn't even have an ambassador. I don't know if he was recalled or something, chargé d'affaires, which is like — it's basically the ambassador without the title of your country having an ambassador. And I can't remember exactly why that was at the time, but we never, ever even had one the whole time I was there we never had one. It is seemingly a very interesting position, but you're right. It's no longer let me send my most adept man to work with the head of this other nation. Now, it's "Hey man, check your Blackberry. You have 20 emails from the 31-year-old who says that you're doing this backwards and you need to be doing this and just show them this document and then go to the zoo because they're opening a new tiger exhibit."

[00:08:57] David Rubenstein: There's probably a lot of that. I mean, a lot of it is doing things that you have to do. But when George Washington was president and he would send a message to his ambassador overseas, it might take two months for the ambassador to receive the message. And when the followed through, it might take two months for the president to hear back. So that was a time when ambassadors really had some authority.

[00:09:16] Today, I don't really think any ambassador has that much authority because they are more or less following the instructions of the White House staff or the State Department desk officer. And there's just not that much maneuverability room.

[00:09:27] Jordan Harbinger: Did you feel qualified to work in the White House in the West Wing? I think you were right in your 20s.

[00:09:32] David Rubenstein: No, I did not feel qualified. I didn't think a lot of other people working with me were all that qualified either. We were all young. Remember, campaigns often have a lot of young people in them because they are willing to take the risk of being a campaign that don't have mortgages and it might not be married yet. They might have families and you have young people. When you win a campaign, you say, "What's the benefit? Well, I'd like to work in the White House for the administration." I got lucky and my boss was close to the president. And so he got a job as being the assistant to the president for domestic policy. I became his deputy and I had an office in the West Wing. At 27 years old, I didn't really know anything. I wish I had the energy I had then and the knowledge I have now, I could do a better job for the country, but I thought that doesn't work out that way. So sure, I didn't feel qualified, but there were people younger than me and people are less experienced than me and less educated than me. So I didn't feel terribly out of place, but I just wished I had known more and a little bit older.

[00:10:20] Jordan Harbinger: When people get close to the crown or they end up in positions near, or with high performers, or they're supposed to be a high performer such as probably your law career, often imposter syndrome kicks in. And it's a running theme in this show where people think like, "I don't know, Jordan." I get this in my Feedback Friday inbox where we answer advice, people say, "I don't know, Jordan. I don't know. I'm only two years in and they're saying they want to promote me. And I'm good. I think I should turn it down because I'm not qualified." And it's just this imposter syndrome that people who are high performers tend to suffer from it more than people who are in the middle or low. In fact, if you want to meet somebody without imposter syndrome, I always tell people, go look at a high school. Those kids know everything. They have no imposter syndrome at all. It's the person, who's the chief of staff, but they're younger than some of the staff on their team. Those are the people that suffer from this. And I wondered if that crept in at all.

[00:11:08] David Rubenstein: Sometimes, if you're reasonably intelligent and hardworking and you're trying to do a great job, you may realize how inadequate you were in the past. And therefore, you tend to get some humility. People who are arrogant and have no humility and think they know it all, they're the ones who have to be careful about because they will probably make mistakes, deal to their hubris or things like that. As a general rule of thumb, I tend to admire people that have a fair amount of humility because they, I think, are smart enough to realize they don't know everything. And I didn't feel like I knew everything in the White House, but I just thought that, you know, for the job I was doing, I wasn't going to do that much damage to the country because I didn't have that much authority.

[00:11:44] Jordan Harbinger: So the safety net was, they don't really let me do anything anyway.

[00:11:48] David Rubenstein: Well, there's so many people around you and the government that you have so many people protecting you and keeping you from doing too much. So it's hard to do too much. That's a big mistake. Though, you know, it is going to be embarrassing if the president calls you and he asks you a question, you're giving an answer and you realize five minutes later, give him the wrong answer. So what do you do? You run down to the Oval Office and say, "By the way, I screwed up," or just hope that somebody else gave him the right answer. What do you do?

[00:12:10] Jordan Harbinger: You hope there's two David Rubenstein on the floor that you're working on. I think that's the strategy.

[00:12:15] David Rubenstein: Well, I would say it can be a problem sometimes. You know, when the president's about to go make a speech and he says, "David, what about this? What's the fact here?" And you have to on the top of your head, say yes or no, or just the fact, and if you get it wrong, he gets blamed but you know you made the mistake.

[00:12:28] Jordan Harbinger: Well, you worked for Carter, right? He's a one-term president. Do you think you would have ended up with a totally different career had he been a two-term president? Would you've gotten more embedded in the Washington scene or the West Wing?

[00:12:38] David Rubenstein: That is a very perceptive question for this reason. When I worked for Carter, I thought he would be a two-term president. We didn't think we could lose from such an old man, like Ronald Reagan, 69 years old. How old can you get? I didn't think you had the energy to get out of bed in the morning at that age, but we lost. And we lost in part because we didn't think anybody could vote for somebody who wasn't as smart as Carter. And we just had what's called cognitive dissonance. We just eliminated all the information we didn't want to believe. And we believed all the information that was consistent, what we wanted to believe. So when we lost, I had to go back and practice law, but I didn't have the skill set for that. So I didn't do a great job. And then I decided I had to do something different with my life and I was young enough to do it. I started a private equity firm that took off.

[00:13:19] Had Carter been reelected, I had no interest in making money at the time. It was no of no concern of me. I would've stayed for a second term. Maybe I would've been the senior domestic advisor or something like that. And then at that point I would've left at the age of 34, 35. I would have been well known enough, so I could slip into a law firm and just easily just solve my access to important people. I didn't have that kind of senior level access when I left Carter because I was too junior. Had Carter been reelected, I would almost certainly have been outnumbered, typical Washington lobbyists, lawyer go in and out of government and never, you know, be heard from and have no money and probably not do the kinds of things I've done.

[00:13:50] So in hindsight, as is often the case in light, I got very lucky when I didn't think I was lucky. I thought it was the worst time of my life. I couldn't get a job for a while, but it worked out okay.

[00:14:00] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned the term cognitive dissonance. I assume that when you learn a lesson like that, like, "How could this happen?" I remember in my 20s is, "How can this happen with the economic crash?" Most of us take those lessons throughout our lives. And if we're successful, we apply them in other areas of our career. I'm guessing that you probably look back at that and think, "Okay, this looks impossible now at Carlyle Group or in this initiative that we're running. But then again, I thought Carter was going to win a second term, so let me reevaluate this." Has that stayed with you, that lesson?

[00:14:30] David Rubenstein: Well, yes, you have to recognize that in the end, making mistakes can help you or failing can help you. There was a famous script writer named Bo Goldman who wrote the movie called Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. You may be too young to remember this, but it was—

[00:14:44] Jordan Harbinger: I've heard of that.

[00:14:46] David Rubenstein: —ended up on them, it's a great movie. He later wrote an autobiography about Hollywood and how it works and he calls it, nobody here knows anything. And what he really meant was nobody really knows when you're writing a movie, if it's never going to work or not, because nobody really knows. It's not predictable. And the same thing is true in life, generally. You know, many times you're doing things and you'd say people around here really don't know what they're doing, but you know, I know a little bit I'll do what I can and you know, maybe it'll work out because I'm not as bad as the other people are here. So whenever you have an idea, you want to pursue it. If you pursue it hard enough, you know, you may think, say other people don't know what they're doing. I'm going to plow through and get this done and maybe it'll work out. So I've tried to do things that other people thought you've been doing. Sometimes they've worked out.

[00:15:25] Jordan Harbinger: You've done patriotic philanthropy, namely restoring historical monuments and things like that. And you mentioned in another interview, I can't exactly remember where it was. I've read it somewhere, but you said you wanted to be historically accurate when it came to, I think Thomas Jefferson's house, you wanted people in part to know that he owned slaves and I wondered why that's important to you.

[00:15:46] David Rubenstein: Well, the theory of studying history is that if you learn about the good and the bad of the past, you can take the good and try to ignore the past and not make those mistakes. That's the theory of history. And that's why we should study it. One of my principles has been, we should learn more about American history so we can avoid the mistakes of the past and also take the best from the past. So at Thomas Jefferson is idealized, as he perhaps should be for running the Declaration of Independence, created the University of Virginia, buying the Louisiana purchase, all those things, he was a slave owner. And he was a very big slave owner. So I wanted, when Monticello was needed some money to repair it, I said, "I'll repair it, provided that you make certain that the slave quarters are built out. And we give the story of Thomas Jefferson as a slave owner." And I think that's important now, not because of me, but other people thought it's a good idea as well. So same is true now with Montpelier IAS that James Madison's home have this slave quarters built out so people could see what it was like there when he was a slave owner. I think it's just important to learn the bad and the good and hopefully, take from the good, the things that we had moved into the future.

[00:16:47] Jordan Harbinger: Are you worried at all that people are trying to whitewash or rewrite history?

[00:16:52] David Rubenstein: Historically, people did. When I went to elementary school or junior high school or high school, you would read textbooks that would never mention that George Washington was a slave owner or Thomas Jefferson was, or that they didn't do any of the bad things that they are now accused of having done. But Thomas Jefferson, I don't want to say it's good or bad, but he did have a relationship with his slave, Sally Hemings for some 40 years. Now, many slave owners had sexual relations with their slaves that they had no control over what the slave owner would do to them. And Thomas Jefferson, you can debate whether it was a love story or whatever it was, but clearly it probably not the kind of policy that we've been saying is a good thing to do, which slave owners taking advantage of their slaves in that way. So I think that these kinds of things should get to be known better so people can look at people and say, okay, he was good. Or she was good. She was bad on some things and bad on other things, but, you know, we should know the good and the bad.

[00:17:43] Jordan Harbinger: We mentioned earlier on the show that you don't donate money to politicians. Do you get involved in politics at all? Or do you shoo that completely?

[00:17:51] David Rubenstein: I'd dropped out of that years ago. I've never given a dollar to a person running for President of the United States in my life. I'd hardly ever given any money at all. Maybe 20 years ago, I gave a tiny amount of money, but relatively speaking of nothing in the last couple of decades. And the reason is, as I said earlier, I want to stay out of politics. Well, I'll give you an example. I started a program which led to my first book, where I would interview a great historian in front of members of Congress once a month. Once a month at the Library of Congress, with the Library of Congress, I will host a dinner and I will pay for the whole thing. So there's nobody who can say I'm taking advantage of government resources. And I do it at the Library of Congress because members can get there easily. I hosted a reception for dinner. I asked members to sit with people from the opposite party, which they do, and this was done to pre-COVID. We'll start it again when COVID is over. And then I interview this person, I wouldn't be able to track Democrats and Republicans if I was seen as an ardent Democrat as an ardent Republican. So I try to be completely apolitical. And take the Kennedy Center, for example, the Kennedy Center, I was appointed initially by George W. Bush. Then later by President Obama, appointed by Democrats and Republicans. I have board members who are appointed by Trump and appointed by Obama. And I just try to stay out of politics.

[00:18:58] Jordan Harbinger: I don't blame you there. I mean, your strategy makes sense. It's obviously though, like on the one hand, right? You're very patriotic. You care a lot about the country. You're working a lot for the country, the history of the country. On the other hand, there's no involvement in politics and that's interesting and it signals — pardon me if I'm reading into this — but it signals, maybe you don't think politics are necessarily the best way to express patriotism. Is that the case?

[00:19:20] David Rubenstein: I do think it is unfortunate that a few decades ago, or maybe longer, the Republican parties kind of latched on to the idea that they were the party of patriots and the Republicans would start wearing little pins on their lapels showing American flag is if Democrats who didn't wear them were less patriotic. And the Republicans did a better job, I think, than Democrats of evoking the idea that they're patriots, because they were either supporting wars that were theoretically patriotic or so forth. I think it's unfortunate that happened.

[00:19:49] And so I have pointed to the phrase, patriotic philanthropy to kind of convey the idea that you can be a patriot by giving money or helping restore historical things without having to say I'm a Democrat or Republican. So unfortunately, I think the word patriotism has been abused a bit, and I regard myself as kind of what I'll call a cultural patriot. I'm trying to give money back and do things that will end with my time and energy to help the country in certain ways. But I wouldn't equate myself with somebody who has given the last full measure of devotion to the country, which is say going to combat it and be killed for it. So now what I'm doing is obviously much easier than going to combat. But I do think that people who go into combat are patriots and people that can do other things to help the country are patriots as well.

[00:20:32] Jordan Harbinger: I wonder what you think of the statute drama with the Confederate statues and some of these Southern states. What do you think about that? I wasn't planning on asking that, but it seems like you probably have an opinion.

[00:20:42] David Rubenstein: Couple of points, one, many of the Confederate statutes are put up, were not put up to honor Robert E. Lee for having led the south in the Civil War. They were put up well after his death, they were put up in many cases early in the 20th century when it became clear that integration or segregation was a major subject for people. And I think a lot of people in the south, one of them says, "We stand for what the Confederacy stood for. And so we'll honor some of the Confederate generals." What I think it was really more to the, I would say, racist somewhat in doing that, as opposed to honoring the contributions, these people may have made to their state. I also think that we should recognize that when you destroy monuments and memorials, you also are destroying history.

[00:21:25] So sometimes we keep things together and around because they remind us of history. So nobody would say that because the pyramids were built by slaves, we should destroy the pyramids, right? Probably not. So you can't destroy everything that's a past because it might've been built in properly, but some of these things have become such symbols of racism and they're really put together and put up to remind people of racism as opposed to honoring Robert E. Lee for other purposes. So I think in some cases, maybe the names should be taken off. In some cases, maybe the monuments should come down or some of them are truly historic and it might've been built for reasons other than just racial.

[00:22:01] Jordan Harbinger: For sure. Yeah. I do think it's hard for me to have an opinion on these sorts of things on this show without causing a crazy, you know, what storm, but there's also a huge difference between the pyramids and these statues in that nobody is walking around Egypt going, "Yeah. You know, my grandfather was forced to build that. I find that offensive." I mean, those were thousands of years old. We're still finding them under sand, right? These tombs and things like that, because they're so old, there is no historical record. There are people walking around Louisiana who go, "I remember when they put that up, I was 11 years old and it was a terrible time in history."

[00:22:33] David Rubenstein: You can go back and look at anybody and find something at fault. George Washington was a slave owner. So maybe some people would say take down the Washington monument. Franklin Delano Roosevelt didn't do enough to, I'd say, help the Jews avoid the Holocaust, some people would say, so maybe we shouldn't honor him. You can't find anybody. Abraham Lincoln, as you may know, is being criticized for an effect having been not against slavery for much of his. And for being an effective slave catcher in the view of some people, because he was enforcing slave catching rules for while. So you can find something wrong with anybody that later is honored. So you have to be a little bit careful or basically, you get rid of everybody who's done anything.

[00:23:12] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. That's interesting. I guess the question is where's the line and I'm certainly not qualified to decide that I don't know about you.

[00:23:18] David Rubenstein: I wouldn't say I'm qualified. I'd say you have to have like most things in life it's gray. If it thinks things in life are black and white, you're often going to be wrong. There's some gray areas there, but I think the best thing to do is to educate people about the pluses and minuses of people. And those people make some judgment about what's appropriate right now. We often have people doing things without a lot of information.

[00:23:39] Jordan Harbinger: Why didn't you say stay a lawyer? You have an interesting opinion on this, namely, when, if you're quoted as saying you can't be good at something, if you hate it. And I can get behind that.

[00:23:49] David Rubenstein: When I went to law school, I did reasonably well, but I wasn't a Supreme Court clerk. So I was on the law review. I did okay. But it was clear I wasn't going to be a law professor or a genius lawyer. When I went to practice law because not all lawyers are genius lawyers or law professors qualified people, but I didn't really enjoy it because in the end, the person making the decisions is the client and you're just kind of facilitating what the client wants you to do. And a lot of it was, I thought, relatively boring kinds of things and mind numbing and not exactly a great use of your gray matter. But I guess I could have done it if I was more successful if people had said, "You're the greatest lawyer we've ever seen, and we want to pay you lots of money to do this stuff." And I'd say,"Well, I'm not that good," but if they think I am, I'll do it. But nobody came up to me and said, "You're that great a lawyer." So I just also came to the conclusion that, you know, life is short and if you don't enjoy what you're doing, you'll never be great at it. Nobody's ever won a Nobel prize and like to say hating what they do. You have to love it. And I didn't love practicing law and clearly it didn't love me.

[00:24:41] So the good thing is I was good enough to be able to practice law and see what I was like and make my mother happy and I got a law degree. But on the other hand, I was not good enough to get stuck in being a lawyer. And, you know, had I done so, I'd be probably retired now by a law firm that says now when you're 70 years old or 65 you have to retire. And I would have made a modest amount of money relative to what I've made in the private equity world. So I have no regrets. My son just went to Stanford law school and graduated. And now, he's in Stanford Business School. He went to both, but he's not interested in practicing law either. Maybe because he saw I wasn't that good at it and he didn't think he'd be that good at it.

[00:25:15] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest David Rubenstein. We'll be right back.

[00:25:20] This episode is sponsored in part by Lendtable. Is your employer offering a match\ your 401k contribution? That's like free money. Most experts will agree that if you don't match out your 401k match, it's like lighting money on fire. But Lendtable realizes that it's not realistic for everyone to set aside enough to maximize the benefits of a company match 401k. We all have lots of day-to-day expenses. That's why Lendtable gives you money to put into your 401k or any other benefits program where your employer offers a match, allowing the money to grow without taking a dollar out of your own paycheck. Then you just paid Lendtable back once you're matched vests, plus a share of the profit that you never would have even had without using Lendtable. The Lendtable team will work with you to make sure you're maxing out your long-term wealth. It takes less than a day to get approved.

[00:26:05] Jen Harbinger: Sign up for Lendtable at L-E-N-D-table.com with promo code HARBINGER for an extra $50 added to your Lendtable balance to start securing your financial future now. Visit lendtable.com today to see how much you can make because it's never too late to start investing in future you.

[00:26:22] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Magic Spoon. Growing up cereal is one of the best parts of being a kid. I had to give it up. I realized it was full of sugar and junk. You probably shouldn't actually eat. Magic Spoon is different. Zero grams of sugar, 13 to 14 grams of protein, only four net grams of carbs in each serving, only 140 calories in a serving. It's keto friendly, gluten-free grain-free soy-free low carb for all your hippies out there. The variety pack has four flavors, cocoa, fruity, frosted, and peanut butter. And I will recommend, mix that cocoa with peanut butter tastes like a peanut butter cup if you're into that. My mom would never let me buy that kind of cereal growing up, obviously. It's as satisfying as a dessert in my opinion.

[00:26:57] Jen Harbinger: Go to magicspoon.com/jordan to grab a variety pack and try it today and be sure to use our promo code JORDAN at checkout to save $5 off your order and Magic Spoon is so confident in their product. It's backed with a hundred percent happiness guarantee. So if you don't like it for any reason, they'll refund your money. No questions asked. Remember, get your next delicious bowl of guilt-free cereal at magicspoon.com/jordan, and use the code JORDAN to save $5 off.

[00:27:23] Jordan Harbinger: Thank you so much for listening to and supporting the show. Your support of our advertisers, that's what keeps the lights on around here. You don't have to worry about writing down the codes of those URLs. They're all in one place there at jordanharbinger.com/deals. Please do consider supporting those who support us. And don't forget, we've got worksheets for today's episode. If you want some of the drills exercises that we talked about here during the show, those are all in one easy place. That link is in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast.

[00:27:51] And now back to David Rubenstein on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:27:56] You set the bar pretty high. I would imagine people — and it's going to be kind of hard and we'll get to this in a bit, but it got to be kind of hard for other people in the family because you know, "Well, look — why can't you be more like your brother or your uncle or your, you know, your grandfather. He's a billionaire." Imagine if you'd retired from a law firm, you'd merely be a millionaire right now. Imagine the shame.

[00:28:16] David Rubenstein: Well, look, I would say that having a lot of money doesn't make you a better person or necessarily make you happier. Continuously, I get introduced as being a billionaire. Well, big deal. There's a lot of people who are a lot wealthier than me. There's no evidence that being a billionaire or a multi-billionaire or centi-billionaire makes you happy. Happiness is the hardest thing to find in life. And a lot of people are happy when they don't have a lot of money. In fact, the happiest people I know don't have a lot of money. Some of the most tortured souls, I know have a lot of money. So you have to really know what you're going to do with the money and doing something useful. It's just going to pile up artwork or houses. It's probably not going to make you. I'm a pretty happy person, relatively speaking, but you know, if you're Jewish, it can't be completely happy, it's my theory.

[00:28:54] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. We're not allowed. We're not allowed to, and as soon as we get close to that, your mother or your grandmother, or both are there to take you down a couple of pegs.

[00:29:02] David Rubenstein: Yeah. So look, I'm pretty happy with where I am, but my biggest challenge in life now is, you know, at 71, my parents made it to about their mid-80s. And sometimes you see people that have genes where the family will get to 90 or 95 or 100. I don't have those genes. Mine are kind of, my family, whole history is around the mid-80s, so I can see I've got a limited period of time. And the question now is what do you want to do during this period of time? So I'm trying to cut out stuff that I don't really do, but so therefore everything I'm doing now, including what I'm doing with you, I enjoy. I wouldn't do it if I didn't enjoy it. I like talking to people who are smart, like you, and giving my views and hopefully other people might be influenced by them. So I enjoy it. And as you know, I do interviewing myself and I enjoy doing that.

[00:29:40] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, you do a great job, actually. I really do enjoy the interviews you have. And as you know, when you're running a podcast, at least a third of it is access to great guests. And that's certainly something that you get an A-plus on with Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos. And I think you've had — was Oprah on there or did I imagine that? I mean she's—

[00:29:56] David Rubenstein: I had her over.

[00:29:57] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I mean, that's a guest roster that any podcast — anyone who does interviews anywhere would certainly envy. So that's great. And you do a good job at the interviews as well.

[00:30:06] David Rubenstein: Thank you. You know, I didn't realize I had that skill. I started doing it a number of years ago. People seem to like it and I kept doing it. Maybe if I'd done it when I was younger, I would be a full-time interviewer, but I'm happy where I am.

[00:30:17] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I think you — trust me. You picked a more lucrative path and now you can have access to all of these great people. You can treat it as a hobby, which honestly I'll tell you interviewer to interview, when I started creating this as a business, it was less fun for at least a decade. In the beginning, it was fun because it was a hobby and I was just doing it and enjoying it much like you probably are with your show. And then it became a business. I think the next eight years were kind of like, I like it, but I miss the days where I could just flick the recorder on and then kind of go, "Hey, I want to talk to this person," and it doesn't matter if it's going to convert or generate sales. And now I'm back there again where I'm just having fun doing it. And it's also making good money, which is just a — I hate to overuse words like a blessing, but it really is. It's just kind of lucky. And also the result of a strategy that thankfully worked out.

[00:31:10] David Rubenstein: As I've been talking about my book recently, I realized a couple of things. One is it seems like everybody has a podcast and there should be a sticker, a honk if you don't have your own podcast. Now, obviously, I'm not exaggerating. There must be thousands of people, tens of thousands.

[00:31:24] Jordan Harbinger: There are over a million and a half podcasts out there right now.

[00:31:28] David Rubenstein: You know, it's just hard to believe and how you rise to the top. You're obviously a very successful one, but rising to the top out of a thousand or a million people it's not easy to do. And sustaining the interest is not easy because people have short attention spans for sure. And getting good guests is a challenge for sure. It's like the SPAC world. I mean, SPAC world is proliferating like podcasts. I mean, see everybody's got their own SPAC now. Everybody's got their own podcasts.

[00:31:48] Jordan Harbinger: Can you explain what a SPAC is? This is something that is specific to investing that a lot of people haven't heard of.

[00:31:53] David Rubenstein: SPAC stands for Special Purpose Acquisition Company. And what it is, is a company that has raised money from typically individual investors and a lot of times it's hedge funds on the idea that if you give them the money, they will take two years to find a company. And as soon as they buy it, that company will be public because the SPAC is already registered with the SEC. So what you're getting is a chance to invest early in a company that you might buy at a cheaper price than would otherwise be the case. There's people running the SPAC theoretically know how to make the company more valuable.

[00:32:26] And so you have a chance to buy something, but if you don't like it, you can sell out of it into the public markets, probably within six months after the investment is made. So it gives people some flexibility. It's very lucrative for the sponsors of the SPAC, because they tend to get 10 to 20 percent of the profits, or not the profits, of the whole company at the outset, which is much more lucrative than you do in the private equity world. Like anything, there seems to be an enormous number of them right now, whether they all can make profits for people we don't know yet.

[00:32:52] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, look, I'm a little naive in this area, despite having worked on Wall Street as an attorney, but that type of thing always makes me a little bit nervous. I was in real estate finance, mortgage backed securities in 2006, 2007, and saw what happened in 2008, because that was why I became a podcast or full time and a radio host. So when I see things like SPAC, I go, "Wait a minute, there's a catch here. Maybe companies shouldn't be allowed to sort of instantly go public after being acquired. I mean, allowed is maybe a strong term, but there's, there's always a catch.

[00:33:24] David Rubenstein: Well, Herb Stein, the former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors under Richard Nixon said famously, he was Ben Stein's father, "Something can't keep going on forever, it won't." At some point, people will say the prices are too high and it's not going to keep going on, but until there's a major crash in the SPAC and people lose a lot of money, I suspect, it'll keep going on. It takes a crash to get people's attention that it's not all perfect. So who knows where it'll turn out, but it clearly is a way to get a company public more quickly than a typical ideal process. And that's one of the reasons why the sellers like it and the buyers like it.

[00:33:56] Jordan Harbinger: How did you pick the name Carlyle Group for the fund? I was doing research. I couldn't find anyone with that name in the organization or the history. I've got this theory that it was like someone's dog or something like that. And you just said, "Hey, that sounds great."

[00:34:07] David Rubenstein: Now what happened is when we were starting a company, we came up with all the usual Greek and Roman names, which either we couldn't pronounce or they were already taken. And then we came up with wonderful things like Washington International Finance and Investment Company, which doesn't roll off your tongue. And so at one point, one of my partners at the beginning said he just read a book about Andre Meyer, who was the former head of Lazard Frere, who had lived in the Carlyle Hotel. He was a single man and he had a single man's lifestyle at the Carlyle Hotel, let's say. And I think this partner aspired to have that single man's lifestyle with the Carlyle Hotel. So he said, "What about the Carlyle?" And it was two syllables. It was sort of available. It sounded British. It sounded upper class. It sounded like we had more money behind us. Maybe we did. So that's how we did it.

[00:34:51] Jordan Harbinger: I wasn't too far off. I mean, it wasn't a dog name, but it was a hotel name.

[00:34:54] David Rubenstein: Right.

[00:34:55] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned in the beginning that you didn't have the fund, the Carlyle Group, you didn't have a Wall Street mindset, but you had a value mindset. So less interested in getting good fees, like Wall Street folks, and more interested in making good investments. So what? So the clients would see results and then word would spread. Was that the theory there?

[00:35:13] David Rubenstein: Well, as you may have heard me say elsewhere, Everett Dirksen, the former Senate Minority Leader, famously said, "When you're getting kicked out of town, get out and pretend you're leading a parade." What is that? Well, basically take advantage of the situation you find yourself in. So I'm in Washington, DC. I don't have any investment banking experience. So what we said is, "Look, we're not investment bankers who have their handout with fees all the time. We're basically people that really will build companies and stay with them. And by the way, we understand companies heavily affected by the federal government better than those guys in Wall Street." It seemed to be true to some extent it, maybe it was. And so that we differentiated ourselves. But if we had been a Wall Street investment banking firm, in terms of backgrounds, we probably would have obsessed over the fee part and not so much the building the value of the company part.

[00:35:56] Jordan Harbinger: What was the phrase, "If you're getting kicked out of town, leave town but pretend you're leading a parade."

[00:36:01] David Rubenstein: "If you're getting kicked out of town, pretend, you know, leading a parade." The lesson is take advantage of the situation you find yourself in. And we found ourselves in that situation, as you know, everybody markets where they can and they take advantage of the attributes that are strong. And that's the attribute we had. We were in Washington, DC. We're not Wall Street, we weren't investment bankers. It seemed like. Obviously, you have a track record in the end.

[00:36:22] Jordan Harbinger: Right, yeah, of course your track record. So it's sort of, you lead with the value mindset and then once you get a track record, you don't really have to worry about it because people say, "These guys are making money, let's throw our money in," right?

[00:36:32] David Rubenstein: Yeah. I mean, obviously to get anybody's attention when you're starting a business, you have to say why somebody should give you money and you come up with reasons. Some will work, some won't. So those are the kinds of things we talked about. But later, if you have a terrible track record, you're telling everybody how great you are as you're going to make a difference. In the end, you have to have a good track record.

[00:36:49] Jordan Harbinger: Long-term thinking such as that, you know, if we go down that road, it really is more long-term thinking, right? The value mindset. It's more and more rare these days. And I'm wondering how you cultivate that among people in Carlyle Group or how you did when you were, you know, every day nose to the grindstone there. Because it's really easy to get short-term when, especially in the United States, in the Western economies, we're looking quarter to quarter.

[00:37:12] David Rubenstein: Well, historically private equity firms, basically we're looking to hold on to assets for six years or so, and their funds were ten-year funds. So you tend to get people who recognize that they're not going to be judged on their annual track record. And they're not just looking at a fee at the end of the year as a bonus. So you get people that want to build companies and are willing to get greater rewards from that, but it takes more time. When you become a publicly traded company as Carlyle, Blackstone, Apollo, KKR, you do have quarterly pressures. And therefore you have to deal with quarterly pressures, as well as making sure that your investors in your funds get the long-term appreciation they want. It's a balancing act, not easy to do. Remember, there are probably 10,000 private equity firms in the world. Now, maybe at least 10,000, but only a limited number of public so that those public ones are the biggest ones. And they tend to have to deal with these issues. I've just talked about it which is balancing the shorter term concern about quarterly earnings with the longer term concern about longer holding periods of time.

[00:38:09] Jordan Harbinger: Do you think your ability to think long-term is a key advantage in other areas of business or of your life, in general?

[00:38:16] David Rubenstein: Well, I think generally, if you're not obsessed with what's happening tomorrow, it's probably better off. And you can plan things down the road because anything of consequence takes more than an hour to get done or a day or a week or something. So anything that's really been built, any great company, Amazon or Microsoft or Apple, these companies took a while to build. And like Jeff Bezos is famous for saying, when all the analysts in Wall Street said, "Hey, your company is going nowhere, you have no earnings." And he said, "Well, I'm building market share. I don't need earnings." And they said, "Oh, no, no, your company is terrible." Well, who had the last laugh? The richest man in the world. Because he focused on building a franchise and he realized earnings will ultimately come as they have now done.

[00:38:56] Jordan Harbinger: Do you feel like — I know you didn't grow up with, by any means with a silver spoon in your mouth, right? So do you feel like your modest upbringing helped you focus on value instead of money? Because I guess if you don't grow up wealthy, you either are obsessed with it, or you don't necessarily regard money super highly, because you didn't have it to begin with.

[00:39:14] David Rubenstein: Well, some people that were really poverty stricken as I've read, you know, they wanted money cause they had absolutely nothing. And they just thought that if I could get money, that life would be better. I wasn't poverty stricken. My father was a blue collar worker. He made $7,000 to $10,000 a year, which was enough to get, you know, support one child and so forth. I would say that I never cared about money because my parents didn't have any money. They didn't talk about money other than say they didn't have enough to buy some things I might've wanted. I would say in those days when I was growing up in the fifties and sixties, there were no billionaires in the United States or in the world. And there were hardly any millionaires.

[00:39:47] And if you were Jewish, you basically were told by your parents to be a doctor or lawyer or dentist, or have you had a family business, you go into a family restaurant business or whatever. People who are Jewish, weren't going to Morgan Guaranty generally, or weren't going to First Boston generally, because those weren't places where people who were Jewish were thought to be rising up and succeeding. So in my case, I just was interested in politics and I thought to go into politics, you should be a lawyer, and that was my skill set. I wasn't really good in sciences as good as I was in other things that maybe a lawyer would have a skill set in. So I just wanted to be a lawyer and go into politics and not make a lot of money. In fact, I couldn't care about money at all because it just wasn't in my mindset.

[00:40:25] In fact, in those days when people were growing up, there were no tech startups. There were no buyout firms. There were no venture capitals. You just have that on your horizon. Today, people coming out of college field, if they don't do a tech startup in first five years to make a billion dollars, they're nothing.

[00:40:38] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. It's kind of a shame, right? I mean, you look at these young folks now, not only they have so much FOMO, so fear of missing out, but you could become a millionaire by age 30 and say, "Ah, man, I've only made a million dollars. What am I doing with my life?"

[00:40:51] David Rubenstein: I agree. And now you could say the same with a billion. I mean, how many people were making a billion dollars before they're age 30. And what are they going to do with the rest of your life? I mean, strange phenomenon, but the people that have made money by and large, with some exceptions obviously, are people that want to prove their ideas work and it got successful and it took off, but it wasn't because they said, "I've got to make a billion dollars because I want to be rich. I want to buy a big house and so forth. Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Steve Jobs, all those people, they were not obsessed with making a large amount of money. They were obsessed with building a company that had really good products and services. And that's what you really have to do if you want to make a lot of money. Don't worry about the money. If you build something good, the money will come.

[00:41:26] Jordan Harbinger: What initially got you so interested in history? I mean, your books, you've written books about history. I've also noticed that a lot of people who are highly successful, especially in finance are very interested in history. Ray Dalio is as well. You guys have that in common, that and rugged, good looks, and billions of dollars. You have that income. But what is it about history that is so appealing to people in your position, generally?

[00:41:49] David Rubenstein: In my case, I worked at the White House. So you do have a sense of history when you're working in the White House. And I worked in the Capital before that, and you have a sense of history because of that. And you live in Washington for 40 years, you have a sense of history. And probably history was a good subject for me in college. And so maybe that's it. Also my mindset wasn't good in chemistry, physics, or biology. So probably I didn't have that obsession with science. But in terms of other people, I just think as you get older and more successful, you kind of look back and say, "Okay, what happened? How do other people do this?" And you know, you probably get it more appreciation of history.

[00:42:18] I like to remind people that very often very successful business people or CEOs do not have a technology background. It's often thought that we have a technology background, you're going to be great. And therefore, you have to be a superstar in STEM or something in college. Many people who rise up on Wall Street or build companies have social sciences or history backgrounds, and so it's important not to ignore those kinds of skill sets, which teach you how to think, which teach you how to read, which teach you how to talk better. All those kinds of skill sets that I think are important.

[00:42:45] Jordan Harbinger: In one interview, you said that you had a gift for running a business. I think, it was, "God gave me certain gifts and one of them is running a business," or something to that effect. And you also said that you'd regretted not giving away more money earlier and getting started and giving and charity earlier. My question is why not simply focus on making money and then have somebody else give it all away for you after you retire or after you pass away? You know, why focus on giving right now, when you said yourself that your gift is actually in making the money? Maybe that's an overly — I'm looking at efficiency a little bit too much.

[00:43:19] David Rubenstein: I don't know whether I said that. Probably, I'm probably better at giving away the money than making it in some ways, but historically when people got very wealthy, John D. Rockefeller's an example, they would hire people to give away the money. And sometimes when they died, they would have foundations created that would give away the money and they weren't really involved in it. But the zeitgeists of this era is that people say, "I've made the money at a young enough age so that I'm young enough to be able to be involved in how to give away the money." So Bill Gates, more or less retired at the age of 50, 51. So he was young enough to not to sit around at the beach. He said, "I'm going to go create a whole different life in philanthropy and actually do things where I understand what I'm giving the money to."

[00:43:57] In my case, I wasn't as wealthy when I was in my 20s or 30s. I just didn't do as much on the non-profit side then, because I was tunnel vision to building my company. When I stepped back a bit in my early 50s, and I decided to go give away all my money, I wanted to do it myself. I don't have a staff. I kind of figure out what I want to do and call up people and say, "I will give you this money." And that's generally what I'm interested in. You know, I intend to give it all away before I die. And I think I'd rather see it be given away and see what's been done with it while I'm alive, rather than somebody's executor giving it away.

[00:44:26] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I mean, obviously I can understand that it's probably very rewarding to establish something and then fund it and get it working quickly and have it benefit so many people kind of right away, or at least very tangibly right in front of your eyes.

[00:44:42] David Rubenstein: Patriotic philanthropy is maybe five to 10 percent of my philanthropy, but it's not 99 percent of what the attention is for, it goes to it's okay. Most of my money goes to education and medical research, particularly education. I have scholarships at all the universities I've been involved with. At the University of Chicago, for example, where I went to law school, I had a full scholarship. And so I created programs, which I think now funded about 60 students a year, at University of Chicago, full ride for University of Chicago students. For a number of years, I'll be doing that. And I have programs like that at Duke or other programs in high schools, in Washington, DC and other things. So I think scholarships are really important to help people get education.

[00:45:18] Jordan Harbinger: I know your mother appreciate you giving away money. You mentioned something about you'd found some scrapbooks. Would you tell us about that? I think that's an important point, actually.

[00:45:27] David Rubenstein: Yeah. My mother rarely called me up and said, "Hey, I just read that Carlyle is going public with the company. And you've made a lot of money." She never called me. She didn't read the business pages, but it wasn't an obsession with her. When I started giving away the money, she would call me from time to time and say, "I'm really proud of what you're doing. You're actually doing something useful with your money." And then after she passed away, I went through all of her materials and she had all the press clips of my gifts put together, but none of the press clips of Carlyle's success.

[00:45:52] So she was obviously proud of the money I'd given away. And after she died, I realized that when I gave her all the money she would take, she didn't want any money. She didn't view herself as a person that should have, you know, tens and twenties of millions of dollars. She didn't want to have that much money, but when I gave her money, she ultimately gave it away. And then after she died, I'm getting now still from organizations that are sending me things that my mother contribute to every organization. You know, if you get a letter in the mail saying, "Can you give $10 to this charity in Iowa?" You're not from Iowa. My mother would always say yes. You know, I got it. Like, you know, 600 of these things. I keep getting letters from people saying, your mother gave us money before, why don't you continue the tradition? Because she gave money to everybody.

[00:46:32] Jordan Harbinger: Well, I suppose it's easier to say yes, than no, right? when those people call anyway.

[00:46:36] David Rubenstein: Seems to be.

[00:46:37] Jordan Harbinger: She's definitely a Jewish mother though. I heard she called you once while you were live on C-SPAN and told you to put a hat on because it was cold outside.

[00:46:44] David Rubenstein: We were announcing the gift to the Lincoln Memorial to redo the Lincoln Memorial. We're sitting there and all of a sudden it starts to snow. And I said to the park rangers in national park, I said to the people, "What are we going to do?" And they said, "Well, we have hats." They were park rangers. We can live in the snow. So let's just get this announcement done. There's a live on C-SPAN. I got a call on my cell phone from my mother saying, "David, I see you on C-SPAN. Put your hat on. It's snowing." So yes.

[00:47:06] Jordan Harbinger: I'm surprised you answered the phone, but I guess you know what happens, if you don't.

[00:47:10] David Rubenstein: Well, if you see your mother's calling you, what are you going to do?

[00:47:12] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that's a good point. I know you read one to two books every week and you're the only other person I know — well, one of the only other people I know who does this — I do it because I do two shows a week and I feel like it would be so rude to have somebody on here and say, "Yeah. So what's your book about, I haven't looked at it yet," right? I wonder if you feel the same way. Do you think your show actually kind of gives you a kick in the pants to make sure you've got the book under your belt?

[00:47:35] David Rubenstein: Yes, because it helps me because I don't feel it's a good idea to interview somebody about his or her book and not have read it. And I have a separate program on the PBS where I interview people about history books, it's with the New-York Historical Society. And like tomorrow night, I'll interview Walter Isaacson about his new book called The Code Breaker about Jennifer Doudna, who just won the Nobel prize for her CRISPR work. And I always try to have books that I'm going to be interviewing authors about with me so I can read them and make sure I know what I'm talking about.

[00:48:03] Jordan Harbinger: It's amazing when I started off interviewing, I thought, you know, I can just read the summary. As soon as you read the book and then have the interview and you realize how much better it is when you actually know what the heck you're talking about, you can't ever go back.

[00:48:14] David Rubenstein: No. Obviously, the trick is I'm generally not interviewing people about things I don't know anything about. So if it's a book on chemistry, I'm probably not going to be a superstar and understanding it, or it's a book on some type of philosophy. I'm not going to be an expert on it, but it was on history, biographies, politics, things like that I'll probably know a fair bit about it already. So it's easy for me to get through the books.

[00:48:32] Jordan Harbinger: You never try and stretch it and go, "You know what? Let me do this interview about genetic sequencing, just to see, because it's an interesting subject."

[00:48:39] David Rubenstein: Larry King famously said he never prepared.

[00:48:42] Jordan Harbinger: Well, let's not use him as an example, then he's not—

[00:48:45] David Rubenstein: He just had a bigger impact than probably you or I are going to have. So he'd never prepared. I wonder why that was, I don't know. You know, as Jim Baker used to say, it was drilled into him, "Prior preparation prevents poor performance." So be prepared and I like to be prepared.

[00:48:59] Jordan Harbinger: So I asked Larry King why he didn't prepare, because I told him that I read the book and he said, "Well, that's a lot more work than I ever did for an interview, right?" And I thought, "Well, okay, but why?" And he said, it interfered a little bit with his natural curiosity, which is an argument that I don't necessarily totally buy. And I definitely have made fun of him for — well, when he was alive, you know, and I would see him, I would make fun of him for this. And in a good natured way, you know, you don't do that with somebody, who's that much more senior to you in your profession or in general. But I would say, you know, of course you should probably prepare a little bit more. And he really loved just asking why and kind of winding the person up and letting them go. But there are famous instances of that really biting him in the butt and embarrassing himself. Did you see his Jerry Seinfeld outtake? His interview where Jerry said, "I didn't get my show canceled. Do you even prepare for these things at all?" It's a little embarrassing.

[00:49:51] David Rubenstein: His career went on for quite a while. I remember when he first started it. Was he on CNN for 20 or 25 years? It's quite a while.

[00:49:57] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, it was a while. And before that he was doing radio for, I mean, probably since like the '50s or something like that, or the early '60s because I remember he told me how he got started. He was sweeping the floor and somebody didn't show up and they didn't have pre-recorded broadcasts they could air on the radio then. It would be, you had dead air, which you don't do in radio. So they said, "Hey, get in here and talk." And that was the beginning of his career. And then I think, you know, 17,000 packs of cigarettes later, and he's got his trademark voice and he got really good at the curiosity thing.

[00:50:28] Although I will say this, look, I love Larry King. I always liked him as a person. I always thought he was a good interviewer in many ways, but I also see that being prepared is better. I don't care how curious you are. Being prepared for your guest is better and you can be curious and prepared at the same time.

[00:50:44] David Rubenstein: Yeah. The trick is sometimes when you're prepared, I've found a couple of times, like for example, I've interviewed authors about books in some cases, they wrote them years ago. And I just got around to interviewing them now for some program. Well, they forgot what they had written and I had read the book recently. So do you then correct the author of the book in front of the author in front of the audience? A little embarrassing when you have to say, "Well, no, you actually said this in the book." So I have to bite my tongue sometimes because if you're prepared and you know more than the author, you go to be careful not to embarrass the author by saying, "You don't really know what's in your own book."

[00:51:15] Jordan Harbinger: That makes sense. In front of a live audience, I can see that being the case. On this show, I will say, "Well, you wrote this," and then my producer cuts it out and then you start talking again and it looks like you knew that the whole time.

[00:51:26] David Rubenstein: All right, well—

[00:51:26] Jordan Harbinger: So I'm willing to make that cheat, just for the sake of the guest.

[00:51:30] David Rubenstein: Okay. I should try that.

[00:51:31] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, try it but I guess if you're in front of a live audience of 30 people and you say, "Well, you wrote right here the opposite of the thing you just said." They might be like, "Why did I agree to this again? I'm never coming back on this guy's show again." You have to be a little bit careful there, yeah.

[00:51:44] David Rubenstein: Well, as you know sometimes you ask questions where the answer is pretty much in the question, which implies you read the book. Now, when you're doing interviews. You've probably heard me say, "The interview format as entertainment is relatively new." And I attribute it to maybe the original Tonight Show when there was somebody before Jack Paar, Steve Allen, and they used to interview people for entertainment as much as information. We don't have interviews of Abraham Lincoln or Julius Caesar, those kinds of people, because they didn't do that format in those days. You know, it'd be great if we could interview them. When you do interviews, you have to make certain you're not overpowering the guests. I won't mention their names, but there are a couple people who had interview shows that didn't last very long because they overpowered the guests. In part because they try to show the guests how smart they were and didn't let the guests answer the question, or they would get into arguments with the guests which definitely not a good thing to do.

[00:52:36] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest David Rubenstein. We'll be right back.

[00:52:41] This episode is sponsored in part by Better Help online therapy. We talk about Better Help a lot on the show. They're renewing their sponsorship. We're killing for them apparently. But this month we're discussing some of the stigmas around mental health. We've been taught that mental health shouldn't be a part of normal life. That is wrong, obviously, I would like to think. We take care of our bodies with the gym, you got to train, or you go to the doctor or you try and watch what you eat, definitely not in December but whatever. We should be focusing on our minds, just as much. And many people think therapy is just for wildly crazy people or preposterous or something. But therapy doesn't mean something is wrong with you. It means you recognize all humans have emotions. We're complex. We need to learn how to control and manage them. Not just avoid the problem. Better Help is customized online therapy that offers video, phone, even live chat sessions with your therapist. You don't have to see anyone on camera if you don't want to. It's more affordable than in-person therapy. You don't have to drive. You don't have to park. You don't even have to get out of bed. You can just do it straight from your phone. You get matched up with a therapist in under 48 hours. Give it a try. Over two million people have used Better Help. Go ahead and see why.

[00:53:41] Jen Harbinger: For 10 percent off your first month visit betterhelp.com/jordan. That's better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan and join over two' million people who've taken charge of their mental health with the help of an experienced professional.

[00:53:53] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Credit Karma. Have you ever tried to get a loan? The rejection can be so frustrating. Whether you're trying to get a credit card or personal loan, Credit Karma can help you find one that works for you. It's completely free and easy to sign up for a Credit Karma account, no effect on your credit score. It'll make it simple to search for the right personal loan for you, and it even shows your approval odds. You can choose offers that you're actually more likely to get approved for, so you can apply with more confidence instead of just setting yourself up for rejection, like me dating all through high school and college. What? On Credit Karma, you can check out multiple loan offers side-by-side. Members who compare loan offers on Credit Karma save an average of 30 percent on interest rates. And once you have a loan, Credit Karma can help you track your progress as you pay off your debt. And even that, you know, if you can refinance and save.

[00:54:36] Jen Harbinger: Ready to apply? Head to creditkarma.com/loanoffers to see personalized offers with your approval odds right now. Go to creditkarma.com/loanoffers to find the loan for you. That's creditkarma.com/loanoffers.

[00:54:50] Jordan Harbinger: Now for the conclusion of our episode with David Rubenstein.