James Clear (@JamesClear) believes that you do not rise to the level of your goals; you fall to the level of your systems. He is the creator of the Habits Academy and author of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones.

What We Discuss with James Clear:

- How a near-death experience began James’ exploration in leveraging tiny habits for giant outcomes.

- The difference between systems and goals and which one you should commit yourself to if you want results.

- What bamboo, cancer, and a winning Olympic coach can teach us about little changes that amount to a lot.

- Why the way you behave depends on the type of person you believe yourself to be — and what you can do to modify this belief for the better.

- What it takes to break bad habits while creating good ones without falling into the “fake it ‘til you make it” delusion.

- And much more…

- Have Alexa and want flash briefings from The Jordan Harbinger Show? Go to jordanharbinger.com/alexa and enable the skill you’ll find there!

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

Massive head trauma forced Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones author and Habits Academy creator James Clear to relearn the very basic building blocks of functioning as himself. But he couldn’t make the change overnight — he had to start with small habits and build momentum that, over time, resulted in big changes. In this episode, he takes us along for the ride and shares processes and practicals we can use to incrementally change our own lives for the better. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

More About This Show

As we learned from recent guests Jane McGonigal and Jim Kwik, finding a way to navigate the aftermath of a concussion can change your life. After suffering his own traumatic head injury, Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones author and Habits Academy creator James Clear concurs.

“I was hit in the face with a baseball bat between my sophomore and junior year of high school,” says James. “It ended up being incredibly serious. The first 10 minutes or so, I was conscious enough to be walking around and answer some questions, but I answered all of the questions wrong!”

Q: What year is it? A: 1998. [It was 2002.] Q: Who’s the president? A: Bill Clinton. [It was George W. Bush.]

It wasn’t long before James had trouble breathing and swallowing on his own, and he suffered three seizures in eight hours. A coma was induced for his first overnight at the hospital, and when he was brought out of it the next morning, he realized he had no sense of smell. To add insult to injury, James’ eye was forced out of place when he blew his nose thanks to the new and numerous cracks in his eye socket.

“It was a brutal injury and it took me eight or nine months to recover,” says James. “Eventually, my eye did go back into place; it took about a month. But that process was — I don’t know if I’d want to say it was a blessing in any way, but it did teach me some lessons. It forced me to start small, because I didn’t really have a choice. I was so injured that I couldn’t have this radical transformation and be back up and running the next day. I had to just focus on building small habits and making little improvements; that was the first place that I practiced that in my own life.”

James considers the tiny, atomic habits illustrated in his book — the ones that helped him regain himself after this lengthy convalescence — to be “the compound interest of self-improvement.” Like a freight train leaving the railway yard, the progress made by just one small habit is nearly imperceptible at first — but as momentum is gained, it becomes unstoppable.

“It’s very easy to dismiss a single choice on any given day — positive or negative,” says James. “It’s easy to be like, ‘Oh, I had a burger and fries for lunch versus a salad.’ It doesn’t really matter on any given day; your body looks the same in the mirror. The scale is the same. You don’t really see how those one percent changes make a difference for you or against you. But you compound that over two or five or 10 years and the consequences of those repeated decisions become very apparent.”

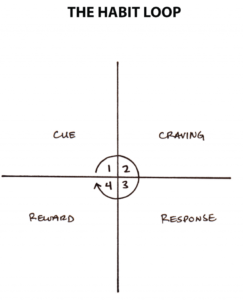

Listen to this episode in its entirety to learn more about how internal and external stimuli affect our habits, the cravings and predictions that precede and influence certain behaviors, how an Olympic coach improved his team’s performance in one percent increments all the way to winning multiple gold medals, what bamboo and cancer can teach us about little changes that amount to a lot, the difference between systems and goals and which one you should commit yourself to if you want lasting results, how understanding the habit loop and the four laws of behavior change can help us make or break habits that stick, and much more.

THANKS, JAMES CLEAR!

If you enjoyed this session with James Clear, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank James Clear at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James Clear

- AtomicHabits.com

- The Habits Academy

- James Clear’s Website

- James Clear at Facebook

- James Clear at Instagram

- James Clear at Twitter

- TJHS 96: Jane McGonigal | Gaming Your Way to Health and Happiness

- TJHS 85: Jim Kwik | How to Unlock Your Brain’s Secret Superpowers

- How 1% Performance Improvements Led to Olympic Gold by Eben Harrell, Harvard Business Review

- What Is the Origin of the Quote Attributed to a Navy SEAL: “Under Pressure, You Don’t Rise to the Occasion, You Sink to the Level of Your Training?” at Quora

- The Habit Loop: 5 Habit Triggers That Make New Behaviors Stick by James Clear

- The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles Duhigg

- Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products by Nir Eyal and Ryan Hoover

- TJHS 48: Nir Eyal | How to Manage Distraction in a Digital Age

- Skinner — Operant Conditioning by Saul McLeod, Simply Psychology

- The Diderot Effect: Why We Want Things We Don’t Need by James Clear

- How to Build New Habits by Taking Advantage of Old Ones by James Clear

- TJHS 21: Benjamin Hardy | What to Do When Willpower Doesn’t Work

- How to Stop Procrastinating and Boost Your Willpower by Using “Temptation Bundling” by James Clear

- How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the “2-Minute Rule” by James Clear

- The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do by Judith Rich Harris

- The Goldilocks Rule: How to Stay Motivated in Life and Business by James Clear

Transcript for James Clear | Forming Atomic Habits for Astronomic Results (Episode 108)

Jordan Harbinger: [00:00:00] Welcome to the show, I'm Jordan Harbinger. As always, I'm here with my producer, Jason DeFillippo. Today, we're talking with my good friend, James Clear. He is an author and a habit change expert. I've known James for a long time now and one thing that I can say about him is, he's the kind of guy who gets obsessed with results, not in a scare-everyone-off-because-he's-so-intense kind of way, but more of a there's-got-to-be-a-better-way-to-do-this-that-works-and-has-lasting-effects kind of way. And that's one major reason that I wanted to get him on the show here to discuss his work, especially his new book, Atomic Habits, which is a freaking masterpiece. I plowed through this thing. It was page after page of habit and behavior change gold. And today we'll get through a sizable chunk of some of this amazing stuff.

[00:00:44] We're going to learn how James almost died from getting a baseball bat to the head. He had to rebuild a lot of his behavior from scratch. And we'll talk about how James created the right kind of environment with internal and external stimuli to get where he needed to go and how you can do the same. We'll explore the difference between systems and goals and we'll see why commitment to a process and not commitment to a goal is actually the key and we'll discover that what you do depends on the type of person that you believe you are. Of course, this all gets into belief structure, identity change, and a set of very specific practicals to go along with it. So when you're done listening to this episode, you'll be well-versed in the science of habit loops, creating good habits and breaking bad ones, structuring the right environment for habit change success, and even how to change who you are at your very core so you can structure your habits and your new life to get what you want out of it.

[00:01:40] I love this book. I love this interview and I think you will as well. And of course, we've got worksheets for today's episode so you can make sure you solidify your understanding of all the key takeaways here from James Clear. That link is in the show notes at JordanHarbinger.com/podcast and if you're wondering, like many of you do, how I manage to book all these great people, have all these great people around me and invest in managing these relationships. Well, I use systems and tiny habits. Speaking of systems and tiny habits, so check out our Six-Minute Networking course, which includes all of those. It's free and that's over at jordanharbinger.com/course. All right, here's James Clear. James, I'm curious about how this all started for you. I know you had a massive concussion and it sounds like the most painful way to get a concussion too. I mean it was just nasty.

James Clear: [00:02:28] Yeah, it was brutal. So I was hitting the face of the baseball bat and that was between my sophomore and junior year of high school. And it ended up being incredibly serious. I mean my first 10 minutes or so, I was like conscious enough to be walking around and answer some questions, but I answered all the questions wrong. “What years is it?” It was like 2002. I was like, “1998”, or like “Who's the president?” and be like, “Bill Clinton”, it was George Bush. And so there's all that stuff.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:02:53] But it was your buddy who did this as an accident?

James Clear: [00:02:55] Yeah. Yeah, it was total accident. And then pretty quickly, I went very rapidly downhill. I couldn't really breathe on my own. I had trouble swallowing. I have all these seizures. I think I had three seizures and the next like eight hours I had to be air cared to the hospital. I was put into a coma overnight. And eventually, the next day I had been stabilized to the point where they kind of release me from the coma and let me try to breathe again. And I realized I couldn't smell. And so they gave me this apple juice box to blow my nose and like try to sniff the box to see if I could smell something. And that worked. I was able to smell it. But when I blew my nose, all this air went through the cracks of my eye socket and force my eye out.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:03:33] How's that? How's that breakfast sandwich there?

James Clear: [00:03:38] So it was a brutal injury. And it took me eight or nine months to recover. Eventually, my eye did go back into place; took about a month. But that process was -- I don't know if I would say it was a blessing in any way, but it did teach me some lessons. You know, it kind of forced me to start small because I didn't really have a choice, right? I was so injured that I couldn't just have this like radical transformation and be back up and running the next day. And so I had to just focus on building small habits and making little improvements. So that was kind of the first place that I practice that in my own life.

Jordan Harbinger [00:04:11] Was there any lasting, aside from your eyeball popping out?

James Clear: [00:04:14] Well, you can see how I look now. I used to be beautiful but --

Jordan Harbinger: [00:04:16] I highly doubt that.

James Clear: [00:04:19] Yeah, I don't know if there was any lasting impact memory-wise but it's also like an impossible experiment to run, right? Like who knows, maybe I would be slightly smarter and I just never knew the difference.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:04:30] Have you had a brain scan since then? I'm curious.

James Clear: [00:04:32] There was a lot of stuff in the first year or two after that, checkups and different things, but I haven't done anything recently and because I haven't had any symptoms present themselves that have been like, you know, serious or impact my life in a measurable way, I don't really think about it that much now. It's been over 10 years now.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:04:47] That's a long time. I did a brain scan with a friend of mine who's a neuroscientist and he gave me a brain scan to play this game that helps you whatever, get into theta waves – it’s a long story that we don't have to get into here. But he goes, “You have a concussion? Or you had one?” And I said, “Nope.” And he's like, “Yeah, you. Here it is” like, “here's the back of your head and here's all this”, I don't know if it's amyloid plaque or whatever, scar tissue in the brain, he's like, “you can work on this for like a couple of years and maybe fix it, but you definitely have a concussion. Did you ever fall?” And I'm like, “Well, who hasn't fallen?” And he's like, “Yeah, it looks pretty serious. Like maybe you fell as a kid.” And I asked my mom and she was like, “I don’t know. I mean you probably, you know, somewhere, but nothing where we took you to the hospital.”

James Clear: [00:05:31] Yeah. That's interesting. I mean, I do visually, I have something like my nose is a little -- it's still hooked a little bit on one side. I have a scar on one of my eyebrows from it and stuff, but I would say it's all fairly much.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:05:43] Yeah. You can't even tell. I mean, I can't even tell when you're telling me about it. So that's always a good sign. It must've been pretty scary. Losing your sense of smell is the least of your concerns when your brain is that swollen, you had to be put in into a coma. So you decided to work on, how did that lead to you being like, “I need to build a habit system.”

James Clear: [00:06:02] Well, you know, I never would have said it that way at the time. I didn't have like language for it. I just knew that I just tried to get a little bit better each day, whether that was recovering, or I just wanted to, you know, in a sense when you have a really serious injury like that, you feel like you've lost control of your life a little bit. It feels like it's out of your hands, you know, like, all this thing happened to me. And so building little habits gave me this sense of control over my life. It didn't radically transform my life overnight, but at least made me feel like, “Oh, I'm in control again.” So I just did little things. I mean, when I went to college a year or two later, I've focused on having my room be clean and like make sure I was prepared for class and it’s like all this stuff is small stuff, but it started to build a sense of confidence a little bit. And this is a little bit the story of my life kind of in a nutshell is the sense that I often start kind of slow. But I just don't stop. And so gradually that stuff accumulated and, you know, I ended up having a really good career once it was all said and done.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:06:55] Yeah, I feel similar about my own habits. People go, “Wow, you know, you're just really, you dive right into something.” And it's like, “Well, yeah”, but then if you look online, for example, Mandarin Chinese people go, “Wow, you learn 3000 words in Chinese and you've been studying for six years”, and you go, if you look online, there are people that have learned this number of words in like nine months. It's just they live in China. They're way more intense. But I also wonder, “Did they leave China? And can they still speak it?” And the answer to a lot of those, if you look down in those threads online is like, “Hey, I forgot all my Chinese, how are you guys keeping up with it?” And they're like, “Oh, we're not.” So really, it's a free train. It's one of those that goes so slow that they can't have it crossroads because it blocks everything for like an hour.

[00:07:37] It's just that it doesn't stop like you said. It's not at the level of intensity, it's the duration in a lot of ways.

James Clear: [00:07:45] I think. I mean, that's kind of a hallmark of Cabot's. And one of the things I say in the book is that habits are the compound interest of self-improvement. And same way that compound interest builds up really slowly. This kind of free train metaphor, it's very small in the beginning. And those little 1% changes don't seem like much. But then you get going and it just compounds to a remarkable degree over time. And habits are like that, you know, like it's very easy to dismiss a single choice on any given day -- positive or negative, right? It's easy to be like, you know, “I had a burger and fries for lunch versus a salad’, that it doesn't really matter on any given day.”

[00:08:17] Your body looks the same in the mirror. The scale is the same. You don't really see how those 1% changes make a difference for you or against you, but you compound that over two or five or 10 years and the consequences of those repeated decisions become like very apparent.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:08:32] Right. It's the next 1100 salads that make a difference. Got you. Both internal emotions and external stimuli affect our habits -- this is an interesting statement that came early in the book in that the way that you feel and things that are happening around you affect your habits. What does that look like in practice? Because I can be damn sure that things around me affect my habits, and that I think most people think that's the only thing that affects their habits. Like, “Well, look, I don't have any good food in the house.” And we'll get to that environmental stuff later on too. But the internal emotions are the one where all of the always kind of quick to say, “Well, this has nothing to do with me. It's just that I'm at a burger place right now, so I have to have – I’m at In-N-Out, I can't not get the fries.”

James Clear: [00:09:16] So I think it's probably true that all human behavior works this way, but I also feel like that might be a little irresponsible or extreme for me to say. So I'm not going to say every behavior is like the same. But I think that it holds up in almost all cases and that is that, we experienced some bit of information which we could call a cue or trigger or prompt or something, but there's some bit of information. Usually, often it's visual. It doesn't have to be, you could, any of the senses could work, but you pick up on something. That's an external cue from the environment. So that's the external influence. Then you interpret that information in some way. And this is where the internal piece comes in. And so, you can imagine two people, for example, who see a pack of cigarettes on the table.

[00:09:59] One person who is a smoker sees those and they interpret it as, “I know I need to smoke right now.” So there's this positive signal in their brain. The other person who's never smoked, it just looks like a pack of cigarettes to them. Same way you have like two people walking into a casino, the jingles and chimes, the casino to one person are just background noise; to a gambler, it's like this signal that sets them off and they need to, they feel as compulsive desire to, you know, play the slots or whatever.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:10:23] That's kind of scary. It's scary, not just for gamblers and smokers. It's scary for anybody who's trying to quit anything that's around you all the time.

James Clear: [00:10:30] Yes. Well, I mean, this is a crucial thing for breaking bad habits is that one of the first steps to take is to reduce exposure. Because if the craving or if that internal prediction arises naturally then you want to cut that off at the source. There are other ways to break bad habits too, but that's a really good first step.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:10:46] Yeah, we can dive into that in detail in a bit as well. I think that that's fascinating because I think for most of us, we think habits are a matter of willpower and some people are lazy and don't have it. And that's why they're overweight or can keep smoking or they just can't get their crap together so they're gambling all the time. There's all these different kinds of labels we place on people, which are all universally negative because we don't want to be that person.

James Clear: [00:11:13] Right. Well, so let me give you an example that's a little less geared toward the good and bad habits. Just shows how this process works in general, which is you can have, say the news plays a story and you could have a Democrat watch this story and you could have a Republican watch the story, same exact news segment, but they interpret it in totally different ways. And so my point there is, that the external trigger is the same, but the internal interpretation of that is different. And the filter that we run our experiences through in life, changes how we respond to it. And so, that's what, in my little habit model, I call it the second step, which is like the craving or a prediction that comes before behavior and the prediction you make or the interpretation you make alters the way that you respond.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:11:54] Your book, Atomic Habits, which we'll link to in the show notes as we always do, addresses both avenues to habit change. So the emotional, the internal-emotional, would you say route or path to habit change and the external route? I don't know if they're two separate routes though.

James Clear: [00:12:08] Well, they're not. I don't think they are, but they often in the past had been talked about that way. So there's been, you know, this whole body of research about external stimuli and a lot of the behavioral psychology research is focused on that. And then there's been this whole avenue of cognitive psychology, which is very focused on your moods and emotions and thoughts, and how those influence behavior. And one of my goals in writing this book was to develop a model or a framework that I felt like integrated the two because it's very obvious that both influence our habits and so we need to have a good way of understanding how that happens.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:12:37 ] Other ways that people fail or they try to radically change a bunch of habits. I remember a friend of mine being like, “Yeah man, I got to stop smoking. And so to do that I think I got to stop drinking and to do that I think I got to stop going out and to do that I think I have to stop sleeping in so late.” And I'm like, “You are -- so basically you want to wake up tomorrow and just not be you.” Right? Not that there's anything wrong with that. You had a lot of crap yet you should probably work on that, but you can't do that. And the example in Atomic Habits is this British cycling team example. And I'm not a huge fan of cycling per se, but I think we've all maybe heard the hints to this where they were, they just smashed. They completely transformed the entire team in ways that are surprising. Like painting the truck white, you know, and tell us about how this worked for them.

James Clear: [00:13:24] Well, so this coach came in, his name's Dave Brailsford and he had this theory, this approach, this coaching style they call the aggregation of marginal gains. And the way he described it was, the 1% improvement in nearly everything that they do, so they just looked for a bunch of 1% improvements related to cycling. So they would do things like get slightly lighter tires for the bike or more ergonomic seats or they had their riders wear these electrically heated over shorts that kept their muscles warm while they were training to help them get a little bit more out of that training ride. And they did this in every area they could think of. And a lot of the ones, like the ones I just mentioned, you know, other professional cycling teams are doing that too. But then there were other things that nobody else was doing.

[00:14:01] So like they hired a surgeon to teach their riders how to wash their hands so that they would reduce the risk of catching a cold or getting sick. They figured out the type of pillow that led to the best night's sleep and had the riders bring that on the road with them to hotels for different events and whatnot. And his theory was, “If we could actually do this right, if we could make all these little 1% changes, then I think we could, you know, win the Tour de France in five years”, that was the challenge he laid out to the team and he ended up being wrong. They won the Tour de France in three years and they repeat it again the next year with a different rider and they've won the last two or three against that. They've won like five, the last six or something like that.

[00:14:34] And then at the Olympics in London in 2012, they won 60% of the gold medals available. And that core idea there, that I think is one of the main philosophies that I take into -- how can we change habits and improve performance in any area? It's this idea that it's not, I say this in the conclusion of Atomic Habits -- It's not a single 1% change that's going to transform your life. It's a thousand of them. And so you need to like make all these small sustainable changes that are easy to do by themselves, but then layer them on top of each other. And this is actually one of the reasons I chose the phrase Atomic Habits for the book, which is that atomic has multiple meanings. On the one hand, it means very small; and I do think habits should be small and easy to do.

[00:15:18] But on the other hand, it means the fundamental unit of a larger system. And that's kind of what we're talking about here. How can we make a bunch of 1% changes, these little atomic choices that layer into a larger system? And then the third and final meaning of atomic is that it's the source of incredible power.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:32] Yeah, that’s kind of what I thought. Initially, I was like, “Wow, nuclear habits – nice!”

James Clear: [00:15:35] Yeah. Well that's kind of like the overall arc of the book is that if you make changes that are small and easy -- the first meaning of atomic, and you layer them together into an overall system -- the second meaning, then you can get the third meaning, which is this incredible power, remarkable result in the long run.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:51] The compound interest of personal development is what you call that?

James Clear: [00:15:54] Habits of the compound interest of self-improvement.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:15:56] Yeah. I like that. Sounds better than what I said, which I can't remember already. There's negative compounding and positive compounding though, right? Like you can compound in the wrong direction.

James Clear: [00:16:06] Sure. I mean, think about stress. You know, so like the daily stress of parenting or of sitting in traffic for a long commute every day or of slightly high blood pressure. Like, those are the little 1% things that are negative or you know, wear on you a little bit, but over 10 or 20 or 30 years, all of a sudden you've got plaque build-up and you have a heart attack or stroke or whatever. And it's really from stress compounding. It's not just one like major event that led to that. And this I think is one of the reasons why understanding habits is so important is that small changes can transform your results, but only if you understand how they work and how to design them to your liking.

[00:16:42] Because habits are sort of like a double-edged sword. You know, they can either cut you down or they can give you a weapon to build you up and like blaze the path that you want and you need to understand how they work so you can avoid the dangerous half of the blade.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:16:53] And before we got on the mic, we also talked about this threshold. You gave a bamboo analogy, which I think is really apt and interesting because I had no idea. Bamboo grows ridiculously fast. That's all I knew. I didn't realize there was kind of a buildup to it.

James Clear: [00:17:06] Right. Well, so this pattern of making small 1% changes, not really seeing much of an outcome and then it compounding, and like exploding later. It's a hallmark of any compounding process is that the biggest returns or the greatest results are delayed.

[00:17:21] So with bamboo it grows these extensive root systems underground for like five years and then suddenly it explodes like 60 feet into the air in six weeks or whatever. Cancer is the same thing. Cancer perpetuates and grows in the body undetectable for a long time and then all of a sudden, you know, take over the body and months, or your habits if we're going to like translate that analogy to this, is kind of the same thing. You know, you show up, what's the reward for going to the gym for three weeks or something? It's not really a whole lot. You know, you show up, yeah, you're sore, you worked hard, your body doesn't really look that different. The scale isn't that different. The outcomes are delayed. And you stick with it for a long time. And that's kind of, there's this, the challenge of that with building any habit is that there's this gap we put effort in early on and we think that our results should increase linearly. It's like, “Hey, I'm working hard. Why am I not seeing something?” And you really need to kind of overcome this little valley of death or this valley of expectations where you're working hard, but you aren't seeing anything so that you can get to the delayed outcomes where the real results are.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:18:27] You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest, James Clear. We'll be right back after this.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:18:32] This episode is sponsored in part by ZipRecruiter. You know what's not smart? Job sites that overwhelm you with tons of the wrong resumes; but you know what is smart, ziprecruiter.com/Jordan. Unlike other job sites, ZipRecruiter doesn't wait for candidates to find you. ZipRecruiter finds them for you. It's got powerful matching technology, which scans thousands of resumes, identifies people with the right skills, education, and experience for your job and then actively invites them to apply. So you get qualified candidates fast. No more sorting through the wrong resumes, no more waiting for the right candidates to apply. It's no wonder that ZipRecruiter is rated number one by employers in the US and this rating comes from hiring sites on Trust Pilot with over a thousand reviews.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:19:15] And right now our listeners can try ZipRecruiter for free at this exclusive web address, ziprecruiter.com/Jordan, that's ziprecruiter.com/J O R D A N. ziprecruiter.com/Jordan. ZipRecruiter -- The smartest way to hire.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:19:29] This episode is sponsored in part by The Great Courses Plus. Now this podcast, it's all about upgrading your mind with wisdom from brilliant people and that's what The Great Courses Plus is all about as well. And that's why I've been a fan for a really long time actually -- years now that I look back on it. It's a great way to learn about virtually anything that interests you. They've got really good instructors; top professors, experts in their field. You can get business topics, personal development topics, but they also have things like history, science, art, cooking, fitness, and there are thousands of lectures and you get unlimited access to those. You can watch or you can just listen anywhere in The Great Courses Plus app. And I recommend checking out the fundamentals of photography. Jen and I were checking this out. Really interesting idea here. First of all, we're all amateur photographers these days, so it's a great way to learn how to take better photos from a Nat Geo -- National Geographic photographer. Great tips and tricks like how to use lighting, frame your photos properly, no matter what type of camera you're using, even phones, you know, who doesn't take pictures of their food these days or a selfie here and there, come on, right?

Jason DeFillippo: [00:20:36] No, I've got a photography degree and I watched these courses and they are spot on solid. So if you definitely want the fundamentals to figure out, you know, your different rules of lighting, your different rules of composition. These are great courses to start with, especially the Nat Geo guys --those guys are top of the game. Yeah, come on. So I highly recommend fundamentals of photography. Even if you're just wanting to get your Instagram action, you know, up to the next level.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:21:00] So now's the perfect time to get started with The Great Courses Plus, we've got a special limited time offer for Jordan Harbinger Show fam and entire month of The Great Courses Plus for free. But to start your free month trial, you need to sign up through our special URL which is thegreatcoursesplus.com/Jordan. That's thegreatcoursesplus.com/Jordan. Let me know what gems you find in there as well. There's a lot of courses in there that I'd love to find.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:21:25] Thanks for listening and supporting the show. To learn more about our sponsors and get links to all the great discounts you just heard, visit JordanHarbinger.com/advertisers. And if you'd be so kind, please drop us a nice rating and review in iTunes or your podcast player of choice, and if you want some tips on how to do that, head on over to JordanHarbinger.com/subscribe. We really do appreciate it. And now back to our show with James Clear.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:21:51] Languages and habits have a lot in common. In fact, of course you need habits to learn languages. I remember the first entire like eight weeks of our Chinese class back when I took classes with a group, was learning the sounds of each letter in pinyin, which is the Roman sort of Anglicised version of these symbols that you see in Chinese because you can't read those. They don't sound like anything. If you're Western, so you have to sound out basically the whole alphabet, and it's hard. And we learned that, we did that for at least six out of eight weeks and everyone just quit. It was like class number one, 22 people. Class number two, the second eight weeks. Yeah, it was like four or five of us and then class number three, before you can really speak, you're just learning all of these little basics.

[00:22:38] There weren't enough people to keep the class going. We needed I think four people, and we just couldn't get it. So I started taking one on ones, on Skype, and then now years later, and this is just a couple of hours a week at most. Now I can have conversations in Chinese. So if I have to learn, if you said learn 25 Chinese words the first month of Chinese, it would be impossible. I wouldn't have any clue. They all look the same. It's just a bunch of squiggles on paper or whatever. Now I can probably. I can learn that in like two days maybe, or maybe even one day if I just had an hour to study. And so you see that your vocab goes up really, really high. And even in the exams that you take for Chinese, the first sort of certification levels, like 120 words and the last one, which is six, it's like 2,500 words.

[00:23:24] So if you look at level six in the beginning, you're like, “There's no way I'm going to learn this.” But by the time you get to the point where you're just memorizing vocab to increase your conversational ability, you could do it all in a few months.

James Clear: [00:23:34] I don't know what the mechanism is there for that and why that happens. But it definitely seems to be true and I think all of us have felt that in some way. We work very hard in the beginning and we don't really see a whole lot for it. And then suddenly you like, I don’t know, crossed this threshold and “Oh, it's easier now.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:23:49] Well, I would imagine it's like any sport. If someone just says, “Hey, go play basketball”, but you've never run, you've never thrown a ball, you've never shot a basket before, good luck. But if you’re already in good shape, you can run, you can shoot, you can pass -- then learning how to shoot three pointers is just a matter of combining different skills.

James Clear: [00:24:06] Well, habits are sort of like the foundation for mastery in that sense. You know, like imagine you're playing chess, you need to know where all the pieces move automatically, without thinking about it. Before you can think, “Okay, I'm going to make this move, then they're going to make this move and then I'm going to do this and respond like that.” That level of strategy and thinking can only come after the fundamentals are habitualized and automated.

[00:24:25] And I think that's true for most areas. You need to like master one unit of performance and then use that as like the stepping stone to the next one and the more habits that you integrate and the more fundamentals you can do without thinking, the more you free up space to focus on like the higher levels of play.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:24:39] And this is called what? The plateau of latent potential.

James Clear: [00:24:42] That idea that the most useful outcomes are delayed and that we work hard for a while without seeing results is what I call the plateau of latent potential. You're not, your work is not wasted. It's just being stored. You know, like I mentioned this quote in the book, that there's this great quote that sits in the San Antonio Spurs locker room and it's about this stone cutter and they say, “Whenever, you know, I don't feel like working.

[00:25:05] Or whenever I feel like giving up, I think about the stone cutter who pounds a stone a hundred times without a crack showing. And then on the hundred and first blow, it splits in two. And I know that it wasn't the a hundred first that did it. It was all the hundred that came before.” And I think that encapsulates what it feels like to build small habits a lot of the time. One single instance does not transform things, but if you're willing to let it compound, then you get something really useful.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:25:27] Is that why some people, I'm sure there's multiple reasons for this, but it seems like that would be a big reason why some people are successful with habit change and others not. First of all, being aware of that idea and then second of all, having the patience to get to that.

James Clear: [00:25:40] There is something about just knowing the idea that makes it a little easier to go through it, right? You know what I mean? If that's your expectation going in rather than, “Oh, well, I'll just work for three weeks and then it'll be done.” Well, yeah, it's much easier to stick with it if you know that that's the game you're playing. But from an even more meta level, yeah, that is the game. I mean, habits -- if you don't do it, if you don't stick with it, it's no longer a habit. So, the main thing is, it's really kind of like an exercise in showing up and starting everyday. If you could just figure out how to get started and you did that for 300 days, then you have a habit.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:26:11] Yeah. Yeah. That pretty much encompasses my entire running career there. And we'll get to that in a bit because there's a lot of things in this book in Atomic Habits where I went, “Yeah, that's how I started running.” I don't run anymore because of joint stuff. It's not like, “Oh I should get back to”, and then unconsciously not doing it. But I went from couch potato to running 10K like all the time. And it was from some of the systems and habits that you talk about in Atomic Habits. First though, I want to discuss systems versus goals because I think a lot of folks,

[00:26:44] especially people who run businesses or have big ideas, they confuse these two things. They've got goals or a dream list or even a dream board somewhere in their house. Don't get me started on that stuff -- but they don't actually have any systems in place or they want, there's people that come up to me all the time, virtually or in real life, that say, “I really want to learn Chinese. I'm working for this company for Apple or something and I got to figure out how to learn this.” And I'm thinking, “So you have a goal to be functionally literate or whatever in Chinese.” And I just kind of go, “Hey Jen, send them the referral email to the teacher that they're never going to use.” Because I already know that unless somebody comes in and says, “I have an hour a week, I want to spend on a language. And I thought about Mandarin, is it possible?” I'm like, “That person's going to learn Chinese”, right? It's going to take a decade, but they're going to be fluent in Mandarin, at some point.

James Clear: [00:27:32] So this is coming from someone who I set goals for many areas of my life and for a long time. I would set goals for the grades I wanted to get in school or for the weights I wanted to lift in the gym or how much revenue I want on my business turn. And at some point I realized, “Okay, I've achieved some of these, but I've failed on a lot of them.” So clearly setting the goal was not the thing that determined whether or not I would achieve that, right? And you can see this in pretty much any domain. There are a lot of the time the winners and the losers have the same goals. Like every candidate who applies for a job, they all want the job. They have a goal of getting it. Every Olympian has the goal of winning the gold medal, right?

[00:28:05] So if the goal is the same between winners and losers, then it can't be the thing that distinguishes between the two. So then I was like, “Well, what does make the difference?” And I would say that it's the systems or process or your habits -- however you want to define that. And one way to think about this is that a goal, achieving a goal only changes your life for the moment, whereas building a system actually changes things for the long run. So if you say you have a messy room and you want your room to be clean, you could set a goal and get motivated and clean your room up now and you'll have a clean room. You'll have achieved the goal. But if you don't change the sloppy habits that led to a messy room in the first place, then three weeks from now you'll turn around and have a messy room again. And so I think a lot of the time people think that what needs to change are the results or the outcome. But what really needs to change is the process behind the results. It's like treating a symptom without treating the cause and habits and systems are the cause.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:28:58] So it's like solving for the input that goes in instead of just trying to figure out how to corral everything into one output.

James Clear: [00:29:05] Yeah. If you fix the inputs, the outputs will fix themselves.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:29:07] Yeah. I think that's really important. And that took me years and years and years to learn. Because of course I, too, had goals and then no real process maybe to get there or a process to get there. But then everything else that's going into that is still garbage.

James Clear: [00:29:21] Well, I would just want to say I don't think goals are useless. You know, like it can be useful to set a sense of direction or to know like what area is important to you. They're useful for figuring out where to focus. But once you've done that, it's probably better to put the goal on the shelf and just focus on the systems and building the habits because that's what actually determines the progress.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:29:39] And in Atomic Habits, you talk about goals first mentality versus systems first mentality. And I liked this because I think there's a lot of people who say, “Well, I'll be happy when”, and that's that goals first mindset where it's “I'll be happy when I get a girlfriend finally.” And then all these other things are going to solve themselves. And that's actually backwards.

James Clear: [00:29:59] Well, you sort of box yourself into this either-or situation. It's like either I achieve my goal and then I'm happy, or anything else happens and I'm not because I didn't achieve the goal. Whereas the system is more like, you're more focused on like a building a certain identity, you know. So let's say weight loss is a really common one. So either I lose 20 pounds and I'm happy or I don't, and you know, I failed. But with the system it's like, well, you know, maybe your focus is on becoming the type of person who doesn't miss workouts or becoming the type of person who sticks to a particular diet or eats, you know, three servings of vegetables a day or something like that. And anytime that you that you are running that system, you're succeeding. You don't have to wait for the ultimate outcome to be happy. And again, this is something that I suffered with for a long time, which is that I was always setting these goals and I was feeling like, “Well then I can be happy when I reached that milestone”, rather than, you know, along the way.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:30:56] I think that's human nature in a lot of ways, especially when you look at the social media era that we're in. We're like, “Oh, I need to have that and this is not me. I don't care about this.” But I see this a lot in my inbox. “Oh, I need to have this cool Ferrari because look at this guy on the internet has one.” And that's like every 17-year-old to 20-something entrepreneur or wantrepreneur on Instagram has that same thing.

James Clear: [00:31:21] Well, because of social media, which I think has exacerbated this and just because of how the news cycle works, newsworthy stories are only about outcomes. And so, when we see outcomes all day long on social and on the news, we tend to overvalue them and overlook the process. Like you're never going to see a news story that is like, a man eats salad for lunch today. Like this is just not right, it's only a story. Six months later when man loses a hundred pounds. That's what you hear. And I think that that causes us to overvalue the goal or the outcome and undervalue the process and the habits and the system behind it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:31:56] That's a good point. We're kind of wired for that almost. And again, I'm no neuroscientist, but it seems like nobody's really interested. I saw a friend of mine actually in this building, in the restroom the other day and I go, “Hey man, haven't seen you for a while. Did you lose weight or did you just grow a beard?” And he goes, “Yeah, I lost 110 pounds.” And I was like, “Oh, I'm really observant apparently”, you know, not like, “Yeah, I lost 15 pounds or 10 pounds -- 110 pounds!” And I'm like, “I knew you looked a little different.” I mean, he lost an entire like person. Yeah. But it's not cool to say like, “Hey, what's your secret?” And he's like, “Yeah, I'm working out all the time, eating regularly, not having 17 pancakes for breakfast.”

[00:32:40] I'm sure that's the system. But everybody just, I'm sure people who want to know how he did it, it's like, “What workout are you doing or what diet are you on?” And the answer is probably really not that interesting.

James Clear: [00:32:52] It's almost always that way. I mean, the fundamentals are unsexy and people know that. We implicitly, we kind of know this, but this is one of the reasons I wrote Atomic Habits is to try to unearth what that, how can we design this process a little bit more? You know, how can we take control of that and, maybe make building the system the fun thing and the interesting thing, rather than getting wrapped up in a particular outcome.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:33:13] Right. Because we got to commit to the process, not the goal. That's the key here. Otherwise, it's less likely to happen. I don't want to say unlikely because a lot of people achieve goals all the time. I would bet that if we found a hundred people who have achieved the goal and we were able to ask them a hundred questions or less, we'd find that they all have systems, or at least the majority have systems.

James Clear: [00:33:34] Well, you can stumble into it, but my question is, can you design it? You know, like, can you take control of the process? And I think you can. And that was, you know, part of what I was trying to do in writing this.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:33:45] I don't know if he did this intentionally, but you adapted the special forces motto that says, “We don't rise to the level of our goals. We fall to the level of our systems.” Did you consciously do that?

James Clear: [00:33:53] I don't know the special forces motto, but there's a famous quote which I have is in the footnotes of the book, by Archilochus. I believe, he is a Greek philosopher. But anyway, he says something to the effect of -- “We did not rise to the level of our expectations. We fall to the level of our training.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:34:10] Okay. So they adapted that from him?

James Clear: [00:34:13] That's the special forces --- So I was thinking about that, and I was like, “Well, this definitely applies to habits”, right? And I think that that's true that we do not rise to the level of our goals. We fall to the level of our systems.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:34:23] Yeah. The original quote I think is something like, “We do not rise to the level of our expectations, but we fall to or default to the level of our training.” Probably isn't default if it's ancient Greek, but whatever. You get the idea, right? It's in the book. If you want to know the official one, you got to have the book.

James Clear: [00:34:36] Yeah. Just check the footnote.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:34:39] Look at the footnotes. There's this onion -- three levels of change. This sort of onion that you created, or that you outlined in Atomic Habits. One is outcomes or goals on the outside. The second one is that process on the inside that we've kind of been discussing, and you hinted at this earlier, the golden child of that little tender, middle of that onion is identity. And I think that's important because that really, when I examined my own goals, achievement, whatever -- it does come down to identity and to just to continue beating the dead horse of my language learning. When I was in high school, I was an exchange student in Germany and that's where I learned German. But before that I was a miserable, terrible French student and I didn't care and I got seasoned French. It was my worst grade in high school, by far. And so I, in air quotes here, wasn't a language learner and my parents and I were very concerned that I'm going to go to Germany and as a non-language learner or someone who's not good at languages, have to then go and learn this even harder language in an informal setting.

[00:35:44] Well, it turns out, humans are actually really good at learning languages, especially when they go into it thinking that they can do it. So I resisted for three to four months in Germany going, “Well, I'm not a language learner, so it's okay that I don't understand and everything.” And then one day I went, “This sucks. I don't have any friends. I've got to figure this out.” And then once I decided that I could probably learn some German, my path to fluency was rapid -- extremely rapid.

James Clear: [00:36:06] Yeah, So I think true behavior change is identity change. And it's this shifting of your self-image or your beliefs or the way you look at yourself. Because it's one thing to say that, I want this and something very different to say, I am this. So you can see how this influences you. I mean, your example there is a good one. People walk around with beliefs like that all the time. “I'm not a language learner. I'm not good at math. I'm terrible with directions. I'm not good at remembering someone's name.” And once you have those type of, once you adopt that identity, it becomes very easy to just reinforce that over and over again. And so, these three levels that you mentioned -- outcomes, process and identity, all three matter. But I think the key is that you want the direction of change to be in the right way, the right arrow.

[00:36:50] So if you start with the outcomes, if you start with the result, then you're like, “Oh, I really want this thing and here's my plan for getting it.” And most people just never think about the identity that comes underneath that. Like they think, “I want to lose weight or I want to be skinny and if I follow this diet, then I'll be skinny.” And then they don't really give any thought to the beliefs behind their behavior. But if you start the other way around, if you start at the identity and you say, “All right, who's the type of person that could lose weight? Well, maybe it's the type of person who doesn't miss workouts.” Then you start with that identity. You say, “Okay, I want to become the type person who doesn't miss workouts. Here are the habits I need to build, and then whatever results come, just come naturally.”

[00:37:24] So most people focus on the results and build a plan and let the identity come naturally. But that rarely works because there are beliefs like conflict with your actions, but if you start with the identity and you build the habits to reinforce that, then the results just could come on their own.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:37:37] So if our beliefs are incongruent with what we want to happen, we're shooting ourselves in the foot consistently, right?

James Clear: [00:37:44] It's really hard. I mean, imagine two people who are trying to quit smoking. The first person, you show them a cigarette and they say, “Oh no, thanks. I'm trying to quit.” And the second person, you show them a cigarette and they say, “Oh no, thanks. I'm not a smoker.” They're both turning it down, but the first person still identifies as someone who smokes. Even if it's like non-consciously, they're like, “Oh, I'm trying to do something that I'm not trying to quit.”

[00:38:05] The second person no longer identifies as a smoker. It's not part of their identity. It's like, “Oh no thanks, I'm not a smoker”, and it's much easier to take an action that is in alignment or congruent with your identity than to do something that conflicts. You might be able to do it once or twice or have the willpower to muster up and you know, push through it, but you need willpower every time. In the long run. It's really hard. It's really hard to stick with the behavior that conflicts with your beliefs and I would say actually, you probably can't do it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:38:31] I would agree with that because for me, to resist a cigarette, I'm not even resisting it. I'm not a smoker. It’s disgusting.

James Clear: [00:38:39] It doesn't bother you.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:38:40] There's absolutely no, if people are smoking around me, I want to leave. I don't go, “Oh man, I wish I could do that right now.” That's the exact opposite.

James Clear: [00:38:48] It works the same way for good habits. You know, like for many people, going to the gym feels like a sacrifice. It's like, “Oh, it takes hard work and effort”, but there are plenty of people out there who are going to the gym every week. It is just normal for them. It doesn't feel like a sacrifice, just like, this is just who I am. And so once you've adopted a behavior as part of your identity, you're really not even pursuing behavior change anymore because you're just acting in alignment with the type of person who already believed that you are.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:39:12] That makes sense. And I had to do that reading. People go, “Wow, you read so many books”, and I'm like, “Talk to me three years ago, and I probably read maybe two or three books in a year. Now I probably read that many a week.”

James Clear: [00:39:24] So that example, right there is a good example of how this process works, which is so that if you believe that this is true, what we're saying, the natural next question is, “Okay, well how do I upgrade and expand my identity?” Like, “How do I shift it so that I believe something new about myself?” And this is where we come back to small habits because it's kind of like every action you take is a vote for the type of person that you believe that you are. And so each time you do this thing, habits are how you like embody an identity.

[00:39:51] You know? So each time you read a book, you are embodying the identity of being a reader. Every time you go to the gym, you're embodying the identity of being a fit person. Every time you make your bed, you're embodying the identity of someone who is neat and organized. And if you embodied that identity enough, if you cast enough votes for being that type of person, it's like the evidence builds up. And as that evidence accumulates, now you have a reason to believe it. And this I think is like a key distinction between the importance of habits and what some people say about like -- fake it till you make it or something like that, right? Fake it till you make it, is asking you to believe something about yourself without evidence, right? It's saying like, “Oh, just fake it and believe that.” But that does not work really well for the brain because beliefs that don't have evidence are called delusional.

[00:40:33] And so if you try to hold onto them for a long time, it doesn't work. The brain doesn't want to latch onto that. But if you can build small habits and accumulate evidence, now you have a reason to believe it -- a reason for that identity to be rooted in something. And this I think is like ultimately one of the real reasons habits matter so much. It's true. They can get you, you know, you can be more productive or you can make more money. You can lose weight. Habits can give you all these things and that's great. But the external results are just one factor. The real reason habits matter is because they provide evidence for the type of beliefs that you have about yourself. And ultimately, you can reshape your sense of self, your self-image, the person that you believe that you are, if you embody the identity enough.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:41:13] So the goal is, and I think this is from Atomic Habits, the goal isn't to run a marathon, it's to become a runner, right? The goal isn't to read the book, it's to become a reader, or to read a hundred books.

James Clear: [00:41:23] Yeah. It's not about one single instance. It's about developing the identity of being that person.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:41:28] I think a lot of people find challenge in this. They say, “Well look, I wasn't brought up to save money or invest or become savvy with real estate or to read books or to be good in school”, and I heard this even yesterday with Freeway Rick Ross, he was like, “Look, I bought a ton of properties before I went to jail. And then they weren't being managed well when I was inside”, and I just thought, “How did you not figure out how to take care of hundreds of millions of dollars, somehow? How did you not just hire like one attorney to maybe manage all this?” And he goes, “Well, you know, my family and friends, we were not brought up to”, and I can't remember exactly what he said, but he basically just went, well, these are all the people and it's very forgivable mistake. Those are all the people he trusted as a career criminal at that point in his life to hold onto his millions of dollars of property. He didn't want to go, “Hey, random-white-dude-who-I've-never-met, here's the keys to my kingdom.” He trusted all these people that were around him and they weren't brought up in this way, but I thought, wow, you know, we all kind of do that, at some level. “Well, my whole family is really overweight, so here I am.” You hear that all the time.

James Clear: [00:42:38] That's it. Yeah. That's an interesting insight. I talk about this in the book when I read about social norms. We are all part of different tribes. Some of the tribes that were part of a really big, like being an American or being French or something like that. And some of the tribes are really small, like being a member of your local neighborhood or being a member of your CrossFit gym or a volunteer organization or whatever it is. But all of those tribes have a set of shared expectations and a set of like shared social norms and habits that, and behaviors in general that align with those expectations, are very attractive and we want to do them. And habits that conflict with those are very unattractive. And so like in that case, it's possible that reaching out to somebody else outside of the tribe would have been a violation of trust in a certain way. And so that's not an attractive thing to do. And that we all experienced that into varying degrees. And so it's hard to figure out the best solution to that, but you need to constantly be assessing your current tribe and think about whether it aligns with the habits that you want to build.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:43:38] You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest, James Clear. We will be right back after this.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:43:43] This episode is also sponsored by DesignCrowd. Crowdsourcing is how busy people get -ish done in the 21st century. And thanks to DesignCrowd, you can focus on running your business while handing over the reigns for your company's logo, web design, tee shirt, you name it -- to a pool of over 600,000 professional designers around the world. And DesignCrowd crowd-sources custom-work based on your specifications and you pick the design you like best. It really is that simple. Visit designcrowd.com/Jordan. Post your brief describing what you want from the art that you need. DesignCrowd invites over 600,000 designers from Sydney to San Francisco to respond and within hours, your first designs will start rolling in and over the course of three to 10 days, a typical project will receive 60 to a hundred -- maybe even more different pieces from designers around the world. And then you pick the one you like best and you approve payment to the designer. And if you don't like any of them, DesignCrowd will give you your money back. So check out DesignCrowd. Jason, where can they find it?

Jason DeFillippo: [00:44:41] Check out designcrowd.com/Jordan, that's D E S I G N C R O W D.com/jordan for a special $100 VIP offer for our listeners, or simply enter the discount code JORDAN when posting a project on DesignCrowd.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:44:56] This episode is sponsored in part by FreshBooks. If you run your own business, I bet you love being your own boss. I love being my own boss, that's for sure, especially this year, Jason? I don't know, something different this year?

Jason DeFillippo: [00:45:05] I don't know. Maybe. Something's in the air.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:45:08] Something's in the air. Endless earning potential. Doing what you love everyday, certainly makes all the admin, all the paperwork worthwhile, but there is an easier way to deal with all those time-consuming tasks and our friends at FreshBooks, which we've been using for like nine years or something, they make accounting software that is incredibly simple to use, which as you might guess, makes accounting way easier and paperwork a thing of the past, which is great. FreshBooks. When I say it's easy to use, here's what I mean. Create and send professional-looking invoices in like 30 seconds.

[00:45:38] Clients pay you through invoices with online payments, which in turn gets you paid twice as fast, right? It's like, “Click here to pay. Done.” It's not, “Please write a check when you get this fax”, right? It's fast. You can do it right in the email that they get. You can also link your FreshBooks account to your credit and debit card so the next time you expense a business lunch, it'll just show up in the FreshBooks account and as a FreshBooks customer for the last decade or so, I've experienced first-hand how all the features can save a ton of time every week, which means I've got a lot more time to work on content for upcoming shows. Jason, where can they get some FreshBooks.

Jason DeFillippo: [00:46:10] Right now, we're giving our listeners a free 30-day trial of FreshBooks for all of our listeners, no credit card needed. Just go to freshbooks.com/Jordan, and enter JORDAN in the How Did You Hear About Us section. And I've been using FreshBooks for five years now, and I finally now that they've got all this great stuff that you can tie your debit cards to, like you mentioned, I can get rid of a bookkeeper which is going to save me a couple thousand dollars a year, so I love FreshBooks. They are making my life easy. Yeah, great stuff. Thanks for listening and supporting the show. Your support of our advertisers is what keeps us on the air. We really appreciate it. And to learn more and get links to all the great discounts you just heard, visit JordanHarbinger.com/advertisers. Now for the conclusion of our show with James Clear.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:46:55] What about this habit loop that you've got here? We talked, we hinted about it. I think in the very beginning cues, this really is like the, I don't know what you, this is the roadmap to habit creation or the roadmap to how habits work.

James Clear: [00:47:09] I think that's right. I mean, that's what I was trying to build when I put it together. So a lot of people were familiar with Duhigg's Habit Loop from Power of Habit or cue routine reward. And that actually kind of had its origins in the 1930s BF Skinner had the stimulus response reward model who's this famous psychologist. But anyway, that is a good example of the external influences on behavior, which we talked about earlier. But we need to account for the internal influences as well. And so my model has four stages. So first there's a cue, there's some bit of information that you come across. Second, there is what I call a craving, which is really the prediction that you make about the queue. And I'll give you an example in a second.

[00:47:48] Third, there's the response. So the actual habit itself or the behavior that follows, I think this model works for not only habits but most human behaviors. And then fourth, there's some kind of result which I would call the reward. There's a benefit that comes from doing the behavior, how it serves you. And these four stages form a feedback loop, and if you repeat them enough, then a habit becomes ingrained or behavior you can do more or less automatically. And it's really what we're describing is really the process of learning. It's how you learn a new behavior, how you learn a habit. So let me give you an example. If you walk into a kitchen and you see a plate of cookies -- see the plate of cookies, that's a visual cue. Next, your brain makes an interpretation or prediction, and we call that the craving.

[00:48:31] So it's like, “Oh, the cookies are going to taste good so I should go eat them.” Then you have the response, you eat the cookie and then the reward is it's tasty, it’s sugary, whatever. And so that closes the feedback loop and teaches you, “Hey, next time you see a cookie, you should eat it again because it's tasty.” But you can just as easily imagine a scenario where let's say you were eating in the other room and you just finished dinner, you just had three cookies, you're full, you walk in, you see another plate of them in the kitchen, and now your interpretation is different. You see the same cue, but you're like, “Oh, I'm stuffed. I don't want to eat anything.” So different interpretation or different prediction, and so now you avoid the cookies. You don't eat anymore, the response is different, the outcome is different.

[00:49:09] And so that's where we account for kind of this internal state. Your internal state determines how you interpret the cue, which then leads to the response. And so that's how we kind of both get the external and the internal influence in this model.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:49:22] And everyone does this. If you don't, if you can't think of an example of the cookies aren't clear enough for you, light switches, phones.

James Clear: [00:49:29] Yeah. Let's say you walked into a room, it's dark. That's the cue. You want to be able to see -- craving, this is somehow a prediction. You reached for the light switch and flip it on -- response, you can see, reward. So I mean that happens in half a second and you do it all the time anytime you walk into a dark room, right? This loop is like endlessly running. And you're doing this without even thinking about it, right?

[00:49:51] You're building habits all the time. Depending on the study you look at, habits account for 40 to 50% of our behaviors on any given day. And this is all stuff like…

Jordan Harbinger: [00:49:58] And does that mean like, anything that we do basically?

James Clear: [00:50:00] Yeah, pretty much. I mean, you know, tying your shoes or flipping on the light switch or unplugging the toaster after each use, like stuff that you don't even think about all the time. You're always using it.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:08] Do you unplug the toaster after each use?

James Clear: [00:50:10] My wife does.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:11] I do too. I can't remember why I started doing that, which is like such a random and perfect example because I thought other people unplug the toaster. I thought we were the only weirdos that unplugged the toaster.

James Clear: [00:50:21] I tried to. I did a lot of research for the book and I tried to find a lot of examples that were things like that. People feel like, “Wait, I thought I was the only one that does that.”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:28] Totally. And I remember like maybe I saw it in the instruction manual for the toaster. It's like, “Hey, there's no off button. You just have to unplug it.”

James Clear: [00:50:35] But then you have to admit to being the type of person who reads the instruction for a toaster.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:50:38] That's true. Jen, do you have any idea why we unplug the toaster after each use? Yeah. We don't know. No clue. Yeah.

James Clear: [00:50:45] Anyway, but it is endlessly running and so you're always, and again, in a way what I'm describing is the process of learning and so the brain is always learning based on what experience you're going through next. And then it updates its predictions and approaches the next time around based on your past experiences and your current situation. And when the situations repeat themselves, when you kind of come across the same context again and again, then you end up forming a habit because you've come up with the same solutions over and over.

[00:51:14] I mean in a sense, habits are like as you go through life, you face problems and some of those problems are big and some are small, like your shoes untied and you need to tie your shoe. And the more that you face the same problem, the more your brain starts to automate the solution, you know? So at first you have to think carefully about tying your shoes. But after you do it a hundred times or 500 times, now you can do it without thinking and you can have a conversation while you're doing it. And it frees up mental capacity to focus on other things. And that's the role of habits. There are these automatic solutions to repeated problems that you face.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:51:43] I always, I was the last kid in kindergarten to learn how to tie his shoes though. So I never understood, there like here's the hard way and here's the easy way, you know. Hard way is two loops and the easy way is one loop and then you do, and I thought, “If there's two ways to do the exact same thing, one is harder, why would anyone learn?”

James Clear: [00:52:01] Why are we all teaching it?

Jordan Harbinger: [00:52:02] Yeah, why would anyone not just do the easy way? And so there's kind of maybe a protest on my part. I am curious what other habits that toaster unplugging, you said you'd researched, you wanted to find things that were other people thought, “I'm the only one who does this.” What else did you find? Because I bet that's interesting.

James Clear: [00:52:17] So a lot of people cover their mouth whenever they laugh. A lot of people apologize before they ask a question. Then it's like, these are just habitual things. They don't even think about it. They're like, “Oh, I'm sorry, but”, and then you know, so there, yeah.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:52:31] I used to cover my mouth when I laugh, but I think it was like an insecurity thing as a kid. I stopped doing it.

James Clear: [00:52:36] Sure. I mean there are a variety of reasons for it, but yeah.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:52:38] Yeah, that makes sense. Yeah. And of course, I'm sorry, but it's like, “I'm sorry for interrupting.” It's again, it's probably a social status thing. You know, if you were the youngest kid or maybe you grew up in a place where you weren't supposed to talk in class, that was a lot of things, “We don't need your questions, just follow what the teacher says.” There's a lot of that. And it might be generational too. That's so interesting. So we can edit the elements of the loop to change our behavior, of course. Whether we want to build a habit or break the habit.

James Clear: [00:53:07] So, I mean this is kind of the backbone of the book, which is what I call The Four Laws of Behavior Change. And so I came up with a law of behavior change for each stage. So for cue, let's make it obvious. For craving, make it attractive. For response, make it easy. And for reward, make it satisfying. And you can think of those four laws as sort of like levers and when the levers are in the right positions; building good habits are easy and breaking bad habits is an easier task. And when they're in the wrong positions, it's really hard. And so they're sort of like, I prefer things that are like a toolbox rather than a formula. I don't think there's one way to change behavior. But there are a set of principles and tools that can work depending on the situation. And there are certain things that kind of do need to be there each time, even if you can do it in your own way. Like I remember I played baseball for a long time, and they would say when you're swinging a bat, you can have your own swing, but at the end of the day, the bat needs to be in the zone to hit the ball, right?

[00:54:04] Like there are certain things that you can't overlook and habits are in a similar regard. Like there's a variety of tools you can use. And then there are a couple of fundamentals kind of everybody needs that doubt in.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:54:14] So The Four Laws of Behavior Change -- let's start with cue and go through these. Because I think some of us who are good at changing our habits, or at least better than terrible, which is where most of us are. We do some of this stuff. But when you really do apply these four laws, you can pretty much do anything. Or you can create any habit or break any habit. I would imagine.

James Clear: [00:54:37] I would say that people probably do a few of these, like you'll be familiar with them, but it's really figuring out how they work together. And honestly, this was where my knowledge was when I started working on the book. I had a variety of ideas that were related to habits, but I didn't have one overarching system for understanding how they all worked. And we talked earlier about the importance of having a system for making progress. And so one of the purposes of writing this book was to develop a system for building good habits and breaking bad ones.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:55:03] So the first law of making things obvious, this itself almost seems obvious, like, “Well sure, yeah. If you keep the spinach in the refrigerator, I'm going to have more salads”, but it's not just that and you're right, it has to be in concert with other things or it's not going to happen.

James Clear: [00:55:19] So here's how to think about it, for any behavior when you want to build or break, you can map it out and think about all the little things that need to happen for that behavior to occur. And then you try to figure out what portions of that you need to make obvious. So I'll give you an example of good habit and a bad one. So for many years, I would brush my teeth twice a day, but I wouldn't floss consistently. And if you map that behavior out, there were a couple things that needed to happen. First, the floss is like in a drawer in the bathroom, and so I just wouldn't remember that it was in there. Sometimes I would just forget about it and never look at. The second thing that sounds kind of silly, but I didn't like the feeling of wrapping floss around my fingers. Like yeah, it was just like uncomfortable. So, I bought some of the pre-made flossers and I got a little bowl and I put them in it and set it right next to my toothbrush. I know. So now it's right next to the toothbrush. And so just that little change of making it obvious, that was pretty much all I needed to do to build that habit. That was the only lever I needed to pull. And now, I do it twice a day without thinking about it. So that's an example of making a good habit.

Jordan Harbinger: [00:56:19] [indiscernible] flossers

James Clear: [00:56:22] Oh, yeah. So that's an example of making it obvious. Then an example for a bad habit, I don't know, like think about a lot of people watch too much TV or don't want to play as many video games to do or whatever. And if you walk into pretty much any living room where do all the couches and chairs face? They all face the TV. So it's like, “What is this room designed to get you to do?”

Jordan Harbinger: [00:56:41] It's the TV room now.