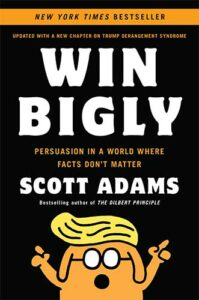

Scott Adams (@ScottAdamsSays) of Dilbert fame revisits us to discuss his book Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter. [Note: This is a previously broadcast episode from the vault that we felt deserved a fresh listen!]

What We Discuss with Scott Adams:

- Is Scott Adams a Trump supporter?

- People don’t use facts to make decisions. They use emotion.

- Learn the three types of persuaders and how they operate.

- See how master persuaders move the topic to things they understand and can dominate (regardless of facts and details).

- Find out why master persuasion is effective even if the subject or target sees the technique.

- And much more…

Like this show? Please leave us a review here — even one sentence helps! Consider including your Twitter handle so we can thank you personally!

Dilbert‘s very own Scott Adams returns to The Jordan Harbinger Show to discuss his book, Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter, and the observations he’s made since Donald Trump’s unlikely victory in the 2016 presidential election.

Listen to this episode in its entirety to learn more about how a master persuader can often get away with making outrageously untrue statements (and why he or she would want to consciously do so in the first place), how someone easily embarrassed today (like, say, a certain bespectacled cartoonist we know) might become immune to shame tomorrow, how otherwise critical thinkers give into the allure of improbably bizarre conspiracy theories, what Scott learned about his own perception of reality by being robbed at gunpoint twice, what we can learn from our own cognitive dissonance, why Scott hates analogies in arguments, the concept of strategic ambiguity, and lots more. Listen, learn, and — if you can’t enjoy, then at least try to understand why we’re where we are today and where we might go next with this information. [Note: This is a previously broadcast episode from the vault that we felt deserved a fresh listen!]

Please Scroll Down for Featured Resources and Transcript!

Please note that some of the links on this page (books, movies, music, etc.) lead to affiliate programs for which The Jordan Harbinger Show receives compensation. It’s just one of the ways we keep the lights on around here. Thank you for your support!

Sign up for Six-Minute Networking — our free networking and relationship development mini course — at jordanharbinger.com/course!

Thanks, Scott Adams!

If you enjoyed this session with Scott Adams, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Scott Adams at Twitter!

Click here to let Jordan know about your number one takeaway from this episode!

And if you want us to answer your questions on one of our upcoming weekly Feedback Friday episodes, drop us a line at friday@jordanharbinger.com.

Resources from This Episode:

- Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter by Scott Adams | Amazon

- How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big: Kind of the Story of My Life by Scott Adams | Amazon

- Loserthink: How Untrained Brains Are Ruining America by Scott Adams | Amazon

- Scott Adams | How Untrained Brains Are Ruining America | The Jordan Harbinger Show 273

- Dilbert

- WhenHub

- Scott Adams | Blog

- Scott Adams | Periscope

- Scott Adams | YouTube

- Scott Adams | Twitter

546: Scott Adams | Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter (Episodes 546)

[00:00:00] Jordan Harbinger: Coming up next on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:00:03] Scott Adams: I was just reading Scientific American on the plane the other day. And they had a fascinating study where they're trying to figure out, you know, what's up with these science deniers. So number one, I don't believe there's any such thing as a science denier. I've never met anybody who thought science was a bad idea. There are people who looked at the same stuff and came to different conclusions. And if you don't like the conclusion that they came to, it doesn't agree with the majority, you got a problem. Well, here's a study in Scientific American that tells you that the number of times we're looking at exactly the same information, there's no data difference. We're smart, we're looking at it and we just come to different conclusions.

[00:00:44] Jordan Harbinger: Welcome to the show. I'm Jordan Harbinger. On The Jordan Harbinger Show, we decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's most fascinating people. We've got in-depth conversations with people at the top of their game, spies, psychologists, astronauts, and entrepreneurs, even the occasional four-star general, national security advisor, or money laundering expert. Each episode turns our guests' wisdom into practical advice that you can use to build a deeper understanding of how the world works and become a better critical thinker.

[00:01:10] If you're new to the show, or you're looking for a handy way to tell your friends about it, we've got episode starter packs. These are collections of favorite episodes organized by popular topics that will help new listeners get a taste of everything that we do here on the show. Just visit jordanharbinger.com/start to get started or to help somebody else get started. Of course, I always love it when you share the show with your friends and/or enemies. It's all the same to me.

[00:01:32] Today, we're talking with Scott Adams. He's been on the show before. This is one from the vault. Yet another controversial episode, because apparently I like getting hate mail, but I highly recommend that people separate their feelings from the subject matter on this one, especially the examples, and just learn. We're talking about persuasion and Donald Trump. And, you know, if you hate Trump, that's fine. You might be sick of it, move to a different episode, but you can still learn some persuasion from this episode in this discussion. I didn't want to spend too much time in this episode, challenging aspects of the work with which I disagreed. In other words, parts of the book with which I disagree, because I really didn't think that would be as useful as the practical parts from which we can learn. So this was a bit of a tough editorial choice for us here, but I think it was the right one in the end because the final product here is much more useful to you as a listener.

[00:02:14] Now, on this episode, we're discussing the persuasion tactics as used by Donald Trump during and before the 2016 election. And whether or not you think that those exist or they're real, or whether or not persuasion itself is real or fabricated. Of course, it covers the 2020 election as well, especially when it comes to the types of skills that we discussed today. It doesn't matter whether you think it's real or not. Either way after this episode, you'll start to look at interactions and things you see on TV and things you see with politicians and executives in a totally different way. And you'll also learn what types of things you can use to identify cognitive dissonance in yourself, how to know if we're being persuaded effectively and persuading effectively, and how to persuade others effectively as well. Again, divorce yourself from the subject matter examples, and try to keep an open mind here.

[00:02:57] And if you're wondering how I managed to book all these amazing people for the show, it's because of my network. And I'm teaching you how to build your network for free, digging the well before you get thirsty, over at jordanharbinger.com/course, and most of the guests that you hear on the show I've met through the course. They subscribe to the course. They contribute to the course. Come join us, you'll be in smart company where you belong.

[00:03:16] Now, here's Scott Adams.

[00:03:20] On a scale of one to 10, how much flack have you gotten since Trump got elected? Because before, when you were predicting the Trump thing, it was a dumpster fire, your Twitter feed. And then afterwards, I would imagine there's some sense of, "Okay, you were right," but most of that's probably more like, "Eff you, I don't care that you were right."

[00:03:40] Scott Adams: Well, a tremendous amount of the Twitter traffic were apparently professional trolls because the moment he got elected, they just all went away and it seems like they would have stayed around a little bit if they were just normal people to say, "Well, see what you've done?" and that sort of thing. But yeah, I would say it went down to 80 percent after election, at least on Twitter. But in terms of the impact on my life, I would say my number of friends is probably down 75 percent—

[00:04:06] Jordan Harbinger: That's a lot.

[00:04:06] Scott Adams: —since I started writing about it.

[00:04:08] Jordan Harbinger: So that you're down to one friend now.

[00:04:09] Scott Adams: Just one friend and he's on the watch list right now.

[00:04:13] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Right. I've noticed that a lot of people have mentioned that they've lost friends because of the political situation. And I think that's kind of a shame. I've got plenty of friends on both sides of the camp. They're probably not people I would want to have over at the same time, all of them. Some of them would be totally fine. There's only a few in each camp that I think are completely insufferable when they start talking about politics. And this has been a particularly divisive election, particularly divisive administration in general.

[00:04:41] One thing that your book Win Bigly focuses on, is the persuasion aspect of Donald Trump, specifically. But during the show, I would love it if possible — it probably isn't, but I'm going to try anyway — to divorce the persuasion concepts from the man himself, because I don't want people to go, "This is about Trump." Click. I want people to go, "Okay. Maybe I hate Trump or maybe I love him. But in the meantime, I'm going to learn something about persuasion." I learned a lot from the book, devoured it in one plane ride, and went away thinking, "Okay, I'm not really qualified to say whether this is all accurate or not, but certainly interesting."

[00:05:19] You did mention your career and your income took a huge nosedive, maybe.

[00:05:24] Scott Adams: Took a hit.

[00:05:25] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, severe hit. What now? I guess now you write a book and you try to make up for this little stop-loss here.

[00:05:30] Scott Adams: Yeah, I don't think the book will make up for the annihilation of my speaking career. I lost a big corporate license deal, and I probably will never get another licensing deal for Dilbert going forward because of writing about the election, yes.

[00:05:44] Jordan Harbinger: Poor Dilbert.

[00:05:45] Scott Adams: So far, the comic itself is fine because newspapers are a little bit immune to the left-right battle. They try to serve both. So I'm fine in newspapers, but that's the only solid place.

[00:05:56] Jordan Harbinger: Really? It seems to me that someone would go, "Hey, we're going to put your cartoon on a mug, but now we just can't do it because it reminds us too much of the president."

[00:06:04] Scott Adams: Yeah. There's some people who just can't shake that association.

[00:06:07] Jordan Harbinger: Wow. If you had to do it all over again, what would you do? Would you do it exactly as you had, or would you maybe sell the Dilbert stuff to a trust or something like that or move some IP around or maybe you'd be Adam Scott on Twitter instead of Scott Adams?

[00:06:21] Scott Adams: You know, I think I'm actually attracted to trouble. That's sort of a lifetime problem with me. You know, I think, "Well, what's the most dangerous thing I could do?" And then I think, "Well, that sounds good." Usually I talk myself out of it. In this case, I probably would have talked myself into it again. I did enjoy, I guess, the fight of it, you know, the intellectual fight of it. But there was something bigger I thought happening during the election, I thought that it would change how people thought about their place in the world. To me, it seemed like a far bigger thing than just one person's persuasion.

[00:06:53] Jordan Harbinger: Sure. Because when I think dangerous, I think, cartoonist.

[00:06:58] Scott Adams: Well, you know, cartoonists do get killed.

[00:07:00] Jordan Harbinger: Oh actually, you know what? That's very true, especially in the last few years.

[00:07:04] Scott Adams: Yeah, the Charlie Hebdo guys.

[00:07:06] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. What was the other one? The Draw Muhammad contest. Is that a filmmaker?

[00:07:10] Scott Adams: Filmmaker, yeah.

[00:07:11] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, adjacent. Artists in general. Now, it's not as safe as it was before. You say that you're in no political camp and you're more of an observer. It's hard to say that when you read the book, because it is about the president's persuasive power. So a lot of folks might really not believe that, but to those folks, I kind of want to say it doesn't really matter whether or not that's true, in my opinion. Looking at persuasion as a skill set, it kind of doesn't matter who we're learning from if that person is effective. There's probably no persuasion class, anywhere rhetoric class, especially anywhere on the planet that doesn't say, "All right, we don't condone this, but here's a bunch of Hitler's speeches. And these were undoubtedly effective for negative results." And I think to omit that kind of case study is to just kind of plug our ears and sing, "La, la, la," and hope that it goes away.

[00:08:02] Scott Adams: Yeah. Unfortunately, there are effective people that we don't like. And if you're just looking at the tools and you can hold your nose and say, "What can I learn?" then you can.

[00:08:11] Jordan Harbinger: You mentioned that when you're a member of a group, you'll find their views more sympathetic. So of course, I have to ask you, is the book then a reflection of, "Well, you know, secretly I am a Trump supporter. So of course, all of these things look like persuasion because they worked on me."

[00:08:26] Scott Adams: Well, I describe myself politically as left of Bernie, except with a preference for the things that might actually work. In other words, philosophically, I want free education, free healthcare and all those things. I don't know how to get there, but I think maybe America could, you know, at least have a plan to get there eventually. So politically, I'm not on the Republican side, but in terms of the first word you used was, you know, "In their camp," but as soon as you said that, I thought to myself, "Well, I am sort of in their camp," because I do represent a point of view, which they like. I do appreciate that group because they're the ones who supported me for two years, whereas the other group attacked me viciously for two years. So I have a strong preference for the people, which is different than the policies or the politicians.

[00:09:12] Jordan Harbinger: I think that it is interesting that we find that when someone strongly disagrees with a certain side's perspective, people then go, "I don't like that. You're even saying that this is a possibility, therefore, I'm going to attack you." Because it seemed to me always a little bit nonsensical to come after somebody who says I'm predicting a Trump win for better or for worse or somebody who's maybe in Silicon Valley would say things like, "Don't keep talking about Trump. You're going to get him elected." Nobody went to that guy and said, "You shut up. We'll talk about whatever we want." They all went, "Oh, okay. That's a good idea." And I had the same problem on this show when I interviewed Roger Stone, people went, "I'm unsubscribing because he shouldn't be allowed to talk." And I thought, "Who made these decisions about who I'm allowed to talk to or about?" And I think that's a weird problem that you have faced more than anybody.

[00:10:00] Scott Adams: Let me bail you out. Let's talk about Colin Kaepernick's persuasion because I'm a big Kaepernick's fan. So when I say fan, it has nothing to do with football, it doesn't even have anything to do with the specific policies he's pushing, although that topic is important, of course. But persuasion wise, Colin Kaepernick nailed it. He raised consciousness. The entire country is talking about the thing that he started. He stayed within the law. He didn't break any laws. He offended our sensibilities in exactly the right way for a protest.

[00:10:32] My image of the America that I want to live in is that, you know, I don't want to flag that I'm not allowed to burn. Like that's not a flag, that it has the same value to me. I'm offended when somebody burns it because it's just an emotional reaction, but I don't want to live in a country that has a flag I can't burn. Colin Kaepernick, I think persuasion wise, this is like the Nobel prize of persuasion. The entire country is talking about his thing. He broke no law. He hurt no people, and he had skin in the game. That's as good as it gets.

[00:11:01] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that's true, right? He's not in jail. Well, I don't know if he got a fine from the owners. It's hard to say, but if he did, it's going to be a drop in the bucket compared to whatever next contract is going to end up with or the one he already has.

[00:11:12] Scott Adams: Well, he doesn't have a contract now.

[00:11:13] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, does he? Oh, well, I guess, I don't know. That shows you one, how much I follow sports versus other items on the agenda. What do you think is going to happen in this situation?

[00:11:22] Scott Adams: I think you suffered quite a bit. I mean, you know a huge portion of the country will never forgive him now.

[00:11:27] Jordan Harbinger: Oh, that's true.

[00:11:28] Scott Adams: And that just will never go away. I don't think there's anything he can do to fix that. I just gave him big props for persuasion. So maybe he has more game than we know, but at this moment, I'd say he put his skin in the game for something he cared about and it's going to cost him, forever, probably,

[00:11:43] Jordan Harbinger: Do you think that it's politically — and I mean that in the broadest sense of the word, beneficial to then alienates certain people like he has done while then, of course, using that same platform to draw many, many people that much closer to him. For example, I didn't care about this at all. He was a name on a Jersey and nothing more. Now, he's been elevated a few tiers up as somebody who's an influencer in a way that actually matters. There are plenty of people who say, "I'm not watching football anymore," and, "Screw this guy." It's almost a worthwhile trade-off in my opinion but I'm wondering what you think about that?

[00:12:16] Scott Adams: Well, it's certainly worthwhile in the sense that he raised the issue that you want to raise and he took the bullet. He knew that this was going to cost him and he did it anyway, so that I have to respect.

[00:12:27] Jordan Harbinger: Is that where you kind of fell on the Trump prediction scale as well? It sounds easy to say, "And that's why I wrote about Trump on my blog." And it's like, people are going to go, "This guy wrote about Trump on a blog, the other guy took a knee in front of the whole country."

[00:12:40] Scott Adams: Well, no, I certainly would never compare myself to any of those individuals. I took some risk with what I was doing, but I did think, and I still think that if you look at the way people talk about the election, the word persuasion is now common. You didn't see that in other elections. You see people referring to a phrase that I'm credited online for being the first to say, which is this 3D/4D chess analogy. So it's become common to think that the way the president operates is through a persuasion filter, and he's got some techniques there, and it's not just all random. And that's what I wanted people to know. I wanted to sort of — it wasn't about Trump so much as opening a hole in the universe to look through, to a deeper truth.

[00:13:26] The main thing I always talk about is the two movies on one screen. The number of times we're looking at exactly the same information. There's no data difference. We're smart. We're looking at it, and we just come to different conclusions. I was just reading Scientific American on the plane the other day. And they had a fascinating study where they're trying to figure out, you know, what's up with these science deniers. So number one, I don't believe there's any such thing as a science denier. I've never met anybody who thought science was a bad idea. There are people who looked at the same stuff and came to different conclusions. And if you don't like the conclusion that they came to, it doesn't agree with the majority, you got a problem. Here's the study in Scientific American that tells you the two movies on one screen vividly. They wanted to find out if denying science had something to do with simply not understanding science.

[00:14:15] The first thing you would test is, "Well, is it just the dumb people." And sure enough, they would find that there were plenty of dumb people who disagree with the scientists, but they also found that across the entire knowledge scale to the most knowledgeable about science, no facts changed their minds. In other words, the data was never a part of the decision to begin with. The fact that some people are saying no and some people are saying yes, is almost certainly because they aligned with a political side. At least in most cases, there have to be some independent minds there somewhere. But in general, people just vote their side and then they figure out why they did it after the fact.

[00:14:50] Jordan Harbinger: I could not agree more. When we had Shaquille O'Neal on the show, he mentioned that he was just joking when he said that the earth was flat. And I got a lot of emails, mostly tweets, because you know how they go on Twitter saying, "No, no, no. The earth really is flat. This is the Freemasons that are forcing him to say that he was joking because this, that, and the other thing," and every single person that I engaged with, because I was genuinely curious. They're really flat earthers out there. I want to know what these people are about universally, they were religious and they were part of a certain church that said the earth is flat and there's the firmament. And that's what the angels live above that. All of the other — and I throw this in air quotes — science, then somehow has to be squeezed into that sort of perspective. And that sort of perspective says, "No. Above the sky is the firmament and above the firmament is heaven. Everything else has to fall into that."

[00:15:39] Scott Adams: Well, I think I've found my new religion because I like to keep it simple.

[00:15:42] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. There you go.

[00:15:43] Scott Adams: Earth is flat, the angels up there, done.

[00:15:45] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Angels up there, bad stuff down there. Just don't dig too far and we're good to go. Yeah. Let's talk about the types of persuader. You go through that early in the book, Win Bigly. What are the different types of persuaders? What are we dealing with on a daily basis?

[00:15:58] Scott Adams: So I tried to help people figure out the different powers that different persuaders have. And so it seemed to me that I'm what I call a commercial persuader. And by that, I mean, I use persuasion for my job. It's part of how I write. It's part of how I make cartoons. It's part of how I write books. And so I'm a commercial grade person. Above me would be cognitive scientists. People actually studied this for a living. As I say in Win Bigly, if a cognitive scientist says, "Hey, this chapter is wrong," believe the scientist, not me. You know, I'm commercial grade, they're science grade. And then above that, I put what I call the master persuaders. These are people who have all the tools of persuasion, but they bring something else, either a high risk appetite, or there's something about their personality that's just gigantic, in this case, Trump has both. So there are people like Steve Jobs, for example, where there's something about his willpower, his, again, appetite for risk and other things that just normal people don't have. But they are above and beyond the tools of persuasion, but you put them together and they're insanely powerful.

[00:17:05] Jordan Harbinger: So, the things that we see master persuaders do are maybe not yet explained by science then? Is that what you're saying? Or there are things that scientists have not studied since they're a rung above on the ladder?

[00:17:17] Scott Adams: So, no, I don't think it's so much the case the science hasn't discovered what master persuaders can do. An example would be a master persuader says something that they know is not true, and they're going to take a lot of flack for it. But in the meantime, they're going to get attention for something that they want attention for. Ordinary people can't do that because they say, "I'm not going to go in public and say something that I know isn't true." But a master persuader, sometimes they say, "Well, you know, it's for a greater good, perhaps, we hope. So I'll shade this. I'll use a little hyperbole. It doesn't really matter in the long run. What matters is where we're heading. And I think that's a good place to go." There's something about the personality that's able to do, what other people would say, "I just can't do that."

[00:17:59] Jordan Harbinger: Right. So it's almost, like you said, a high appetite for risk and/or something that makes them almost immune to the social consequences or ignorant in a way that makes them just not care at all.

[00:18:11] Scott Adams: Immune to shame.

[00:18:12] Jordan Harbinger: Yes.

[00:18:12] Scott Adams: It's a big deal.

[00:18:13] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:18:13] Scott Adams: So if you look at my arc, transitioning from cartoonist to guy who was writing about persuasion and stuff, that was a risky transition and we see the risk and all the friction that it caused, the cost to my main business, the attacks that I got online and everything. But I'm at a point in my life where I liked the risk and I'm almost immune to shame. It is a learned skill to be immune to other people's opinions and just sort of brush it off and move on.

[00:18:42] Jordan Harbinger: Well, let's talk about that. How do we learn that skill? Because there are plenty of people that have nothing to be ashamed of, but do have unpopular views that would love to know how they make that happen.

[00:18:52] Scott Adams: Number one way is to be embarrassed a whole bunch of times, and then look back a month later and say, "Oh my day today is exactly like, it would have been if that had never happened.

[00:19:02] Jordan Harbinger: Right. The real life consequences were I was embarrassed temporarily and nothing more.

[00:19:06] Scott Adams: Yeah. I took the Dale Carnegie course. I may have mentioned that last time we talked. A small part of the course is they actually have you embarrass yourself intentionally in front of the class. But I found that really, really helpful. It even helps with things like public speaking because you're thinking, "Oh, what's everybody thinking of me." The Dale Carnegie course just lets you just let go and just act natural. And that's the safest thing you can do. So it's the worrying that causes the problem. You think, "Well, I better worry about this because this is a potential problem," but the only problem was the worrying. Once you get rid of that, it solves itself.

[00:19:38] Jordan Harbinger: So essentially, we can go back and maybe journal sometimes where we felt really embarrassed and then examine the lasting consequences thereof.

[00:19:46] Scott Adams: Well, yeah, it's an ongoing process. And one of the things I got going for me is that I'm old, right? So I'm 60.

[00:19:52] Jordan Harbinger: I didn't notice.

[00:19:53] Scott Adams: So the number of times that you've been embarrassed, presumably is far fewer than the number of times I have.

[00:19:58] Jordan Harbinger: Especially recently you've been racking them up, I see online, I think. Whether you've done so intentionally or not, and I think a lot of people have it out for you and this is probably not going to help. What do you think?

[00:20:08] Scott Adams: Oh yeah. I think my popularity will plunge to a new low, but with books, people buy books to hear their own opinion expressed better, at least political books. Now this particular book, my book has information in it about persuasion but still people are going to say, "Well, you know, you're talking about this topic and I'm on the other side. So I'm not even going to listen to the persuasion." So what I expect is it will be a polarizing book, but it may not be bad for sales because you're better off exciting a small group of people who actually act than to be pretty good to a bunch of people.

[00:20:44] That's the Hollywood model. The Hollywood model is if you're testing a pilot for a show and everybody who's in the test audience says, "Yeah, that's good. I'd watch that show. That's pretty good." That means nothing. You want 10 percent of those people to walk out and say, "Good Lord, this is the best show I've ever seen. Tell me when this is on. Can I get a copy of the tape?" So you need excitement from a small number that predicts success better than a lot of people saying, "Yeah, that's pretty good."

[00:21:11] Jordan Harbinger: You're listening to The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Scott Adams. We'll be right back.

[00:21:16] This episode is sponsored in part by SimpliSafe. When SimpliSafe home security's founders, Chad and Eleanor Laurans designed their first security system in their kitchen, they did it for a very personal reason. Their friends had just had their home broken into, and I know how that feels, it sucks. They were struggling to find a security system that was simple to set up and would make them feel safe again. Making people feel safe is what SimpliSafe has been doing. Ever since that moment, 15 years ago. A passion to protect people, not only drives every engineering detail on the product, but it motivates every interaction with its customers. SimpliSafe has highly trained security experts ready whenever you need them, whether that's during a fire, burglary, medical emergency, or even when you're setting up the system. I can just imagine people just calling just to chat to somebody. Hit the lonely button on your SimpliSafe. There's always someone there who has your back to keep you safe and make sure you feel safe.

[00:22:04] Jen Harbinger: As our listener, you can save 20 percent on your SimpliSafe security system and get your first month free, when you sign up for interactive monitoring service, just visit simplisafe.com/jordan to customize your system and start protecting your home and family today. Again, that's simplisafe.com/jordan.

[00:22:21] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Everlane. It's been perfect weather for enjoying some shaved ice, some iced coffee, wearing a classic t-shirt. Some of the greatest pleasures in life are also the simplest. That's why Everlane makes premium quality essentials that compliment every wardrobe at a more transparent affordable price. Everlane has got everything from workout to take out, swimwear to track wear, styles for lounging at home or heading up your favorite late night spot. On the hunt for the perfect denim, Everlane has got skinny to relaxed, slim to athletic fit. Choose your stretch level, vintage style, rigid, original with just a hint, or body hugging, authentic stretch, which I will not do to you or to myself. All made from certified organic cotton at the world's cleanest denim factory with zero landfill waste, which is kind of amazing actually. I'm a fan of the organic cotton v-neck tee, an essential in every closet. I love the softness and how it keeps shape through washes and heavy enough not to show any skin or, you know, like my nips or anything. Perfect one alone or as an undershirt.

[00:23:15] Jen Harbinger: Go to everlane.com/jordan and sign up for 10 percent off your first order plus free shipping and get easy returns within 30 days of your ship date. That's 10 percent off your first order when you go to everlane.com/jordan and sign up.

[00:23:27] Jordan Harbinger: Now back to Scott Adams on The Jordan Harbinger Show.

[00:23:32] This little certainly polarized a lot of people. I think people who support the current administration are going to go, "Yeah, this is amazing. I'd never noticed all this stuff. It's so enlightening. Now I got to go rewatch all this video. I'm going to be looking at him." I will say that even now having read this and not necessarily by any stretch, falling into one of the mainstream political camps that — I'll give you this — it'is become a lot more interesting to watch the president speak, because now I can look for the persuasion things instead of just saying, oh, what fresh hell is this now with the climate thing or whatever.

[00:24:02] And I wish that we had a book about this for pretty much anybody that we had to watch, that we didn't necessarily like for the next period of several years. And I will say also that the examples in the book, they're going to ruffle some feathers — I think some of your best media that's going to sell a lot of this book are going to be people that just skewer the crap out of it, whether they do a good job at that or not. I think you're going to have a lot of rebuttal pieces from some of those reviews online, and you should just warm up that keyboard and have a replacement ready because you're going to be doing a lot of typing, I think.

[00:24:32] Scott Adams: It's going to be really challenging for reviewers, I think. I think they're going to have a tough time for it for the same reason, the public will. They're going to try to separate the politics and their view of things from the actual book. I'm going on The Morning Joe Show, when I do tour.

[00:24:46] Jordan Harbinger: They're starting it at the expert level.

[00:24:49] Scott Adams: They're going into the lion's den. I can't wait. That'll be fun.

[00:24:51] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, that should be interesting. I often wonder though, how many journalists that interview you read the stuff that you put out before they do the interview, or if they just get five bullet points from an intern and then try to wing it.

[00:25:02] Scott Adams: Well, in the case of a book, it's actually rare for somebody to read the book. So you're actually in a rare territory having consumed it before I got here. I would say no more than one in eight or 10 maybe.

[00:25:15] Jordan Harbinger: It seems like that would be a huge advantage if you want to debate somebody about a book that they've written, that you might want to go ahead and read it first, or at least part of it.

[00:25:22] Scott Adams: Well, it certainly gives me some freedom.

[00:25:24] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:25:24] Scott Adams: It's like, as I said in the book — well, you would know that.

[00:25:27] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, exactly. All right. People don't use facts to make decisions. That was one of the major points in the book. Tell us why that's true. Because a lot of people go, "Nope. All my decisions are fact-based and I am empirical. And that's what's good about my decisions is they're all based on facts."

[00:25:41] Scott Adams: Yeah. Everybody thinks that. I think there was a recent study. I wish I could quote it, but something like 98 percent of people would just won't change, no matter what facts you give them on politics. People will change on things they don't care about. So if you were to imagine this on the graph, the more they cared about it, the less likely they're going to change, which seems backwards, right? More emotion, the more likely their mental processes are short circuited.

[00:26:06] Jordan Harbinger: Right, because of all the fallacies, confirmation bias, sunk cost fallacy, there's a lot of emotional investment in anything that you feel strongly about. By definition, you're investing more and more emotion in that, which would make you more and more wrong in the past if you change your mind moving forward. Which is why we see remarkable people who do things like leave the Amish and join the rest of the world. We find that amazing or somebody that shakes off severe issues growing up in the middle of rural Africa or something like that, and becomes some sort of tech entrepreneur, those stories are amazing because of the amount of investment that somebody has in a certain way of life or a certain set of thoughts, religion, or otherwise.

[00:26:47] Scott Adams: Let me give you a little example, that's a current one. So after the Vegas shooting, there's lots of talk about this security guard, Jesus Campos, and you know, "Where was he?" And a lot of people came up with conspiracy theories. And they were so sure their conspiracy theory was right, that this security guard must have been somehow connected with the shooter, that when they produced the actual picture of him and then people compared it to, I guess, an older picture, which they knew was actually him. And they said, they put them side by side on Twitter, and they said, "Clearly not the same guy. They've replaced him with a body double."

[00:27:19] And I looked at the pictures, I don't buy into the conspiracy theories and therefore I have no emotional investment. I simply didn't think that was the thing. I look at those pictures and I think, "That's exactly the same guy. It could not be more obvious. I'm looking at them. Two pictures next to each other. Clearly the same guy." But other people — honest, smart, completely normal people who can hold jobs — looked at those pictures and said, "Oh my God, one on the left is a whole different person.

[00:27:46] And when you see it that starkly, you're actually standing in the room with somebody who was looking at the same simple thing and they're seeing it differently. It's amazing. It just tells you how powerful this is. And that was only with just a little bit of, you know, mental investment in their prior opinion and they still couldn't shake it with a photograph. It could not have been clear, in my opinion.

[00:28:06] Jordan Harbinger: Do you think we're evolved to see that way? We actually had a brain scientist on the show earlier, and I can't remember which brain scientist it was, but she was saying that one of the things they're studying right now are a lot of these police shootings. And they're thinking that the police are actually seeing dangerous weapons because their brain is painting a completely different picture. And she thinks that with more advanced brain imaging in the next 10, 20 years, we're going to be able to see that people who make grave mistakes like that based on negative stereotypes, maybe of the race or ethnicity of the person that they're involved with, they're actually seeing something completely different than we're seeing on a video, which is why it looks so bad on the video. Because we look and we say, "How did you think that guy was armed and running towards you when he was unarmed and running away from you?" If we one day get to the day where we can replay what they saw in their brain, somehow, we'll see exactly what they said, which is, "He was running towards me and he had a gun in his hand."

[00:29:01] Scott Adams: You've probably seen the famous video of the people passing a ball around and then the monkey joins the circle.

[00:29:07] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. This guy in a gorilla suit or something, walks by slowly.

[00:29:10] Scott Adams: He actually joins the circle for a moment.

[00:29:12] Jordan Harbinger: Really?

[00:29:13] Scott Adams: And because you've been asked to count the number of passes that they pass back and forth. People don't see a man in a gorilla suit, joining a small group of, I don't know, five people in a circle. After they tell you, and then you watch it, you think, "I was blind to a giant monkey on screen and I didn't even see it."

[00:29:33] Jordan Harbinger: I thought it was a fake video where it played twice in one had the bear or the monkey or the gorilla, whatever it was and one didn't. So I actually rewound it and rewatched it. And then I reloaded it from an incognito tab in Chrome, thinking, "Oh, it knows that I'm back because there's no way that I missed this." If you show it to somebody who's not aware of what the test is testing, you will find that they miss it, almost a hundred percent of the time.

[00:29:54] Scott Adams: I was once a bank teller here in San Francisco. And I got robbed at gunpoint.

[00:29:59] Jordan Harbinger: During the middle of the day?

[00:30:00] Scott Adams: During the middle of the day.

[00:30:01] Jordan Harbinger: So it was a bank robbery.

[00:30:02] Scott Adams: Bank robbery, which actually is very common. Most of the local branches get robbed on a regular basis, but you don't even know it if you're in the lobby of the bank. It's usually just a quiet transaction. You know, "Give me your money," they do, the guy leaves. Of course, the FBI and police or whoever it is, comes by and they say, "Give us the description." So I described him and keep in mind, he was right in front of me. He was at my window, the bank teller window, and I had a good look at him, right? And I said, "Oh yeah, he was about my size. He was about 5' 8", and he had salt and pepper hair and he was sort of bald. And he hadn't shaved for a while and he had a long trench coat." And I had a really good image. In fact, I still have it in my head, a perfect image of that guy. I get a call from my boss and he goes, "They're wondering if you really pulled the secret alarm." Well, it tells you where the camera's supposed to be looking, at what point they're supposed to be looking. And they said they can't find that guy on the video when they play it back.

[00:30:56] So I actually went to the top secret FBI headquarters, the place that they look at the tapes, and they said, "Is this guy on the tape, the guy who robbed you?" And I said, "No, that's not even close." The guy on the tape, he looked like 35, like a young Clint Eastwood with this big bushy brown mustache, full head of hair and a sport jacket. Could not have been further from the guy that I clearly saw. Then they played it backwards in slow motion. And I watched that complete stranger rob me. So there was no ambiguity when you saw it on tape. He actually was robbing me, but my memory was an entirely different person. And you know, the FBI said, "You know, don't even worry about it. That's actually kind of normal."

[00:31:37] Jordan Harbinger: Who do you think that robbed you? I mean, did you pick that guy out of a movie? Was it just somewhere stored in the memory banks, from a TV show you saw as a kid?

[00:31:45] Scott Adams: Who knows because, you know, you're under duress and then your brain just doesn't act normally. You convince yourself, you saw something, you didn't see.

[00:31:53] Jordan Harbinger: Right but when you're trying to theoretically flight or flight, your brain is not saying, "It's going to be important for you to remember exactly what this person looks like for later." Your brain is thinking, "How do I get out of here without getting shot in the head by this crazy person?"

[00:32:06] Scott Adams: And then there was a second one, second time I got robbed, he actually put the gun up to my nose. So he actually took out a gun and held it right up to my face and said he would shoot me if I didn't give money, which is really scary because you're pulling the silent alarm while you're looking down the barrel of the gun.

[00:32:21] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:32:21] Scott Adams: And he knows it. It's a really scary situation. I was dumb to have even pulled the alarm. I should've just given my own wallet and said, "Hey, take what you can." But I gave him the money, and eventually I got asked to be part of a lineup, picking a guy out of a lineup, and I recognized him immediately, but he was also the only one smiling, and the other people in the room, because he'd robbed several banks.

[00:32:42] Jordan Harbinger: Right.

[00:32:42] Scott Adams: Several witnesses, we all picked the same guy. And I always wondered after that day, was it because he was the only one smiling? He was going out of his way to look like he wasn't worried the others were actors. So they were trying to act like a guilty guy and he's the only one who wasn't. So I always wondered, did I really recognize him or did that cue me that he must be the guy?

[00:33:01] Jordan Harbinger: So if you're in a lineup, try to just look like everybody else in the lineup, don't try to look like you're relaxed.

[00:33:06] Scott Adams: I'm hoping to avoid that lineup situation.

[00:33:09] Jordan Harbinger: Right. So why is this concept important that humans use emotion instead of facts to make decisions?

[00:33:14] Scott Adams: I call this the hypnotist point of view. So I'm a trained hypnotist. One of the things that you sort of have to believe in order to even do hypnosis and understand it and work with it, is that people are irrational about 90 percent of the time. 10 percent of the time on the little stuff they don't care about, they can do fine. But the common view of the world is exactly the opposite of that. The common view is that we are rational 90 percent of the time. And about 10 percent of the time, we get emotional, things go crazy. If you use those two filters on life and say, "Okay, which one is explaining things better?" The irrational filter just wins every time. That doesn't mean it's true, because we may live in a universe where we're just fooled about everything, who knows? But certainly as a filter to predict things, it's very true. Just look at the fact that two people can look at the same data with the same IQ, same backgrounds, and just see different things. Actually, literally, see different things, like we were just talking. That's completely irrational behavior and it's the norm, it's not the exception.

[00:34:13] Jordan Harbinger: One of the concepts in Win Bigly is that things we think about all the time rise, a couple of rungs up on the ladder of importance in our minds. You gave a lot of really interesting examples of this and the way that Trump uses these examples to persuade. Can we explain and give some examples of this? Because that explains a lot of why these facts and assertions and things like that come out of his mouth seemingly for no reason. And a lot of us just smack our foreheads and think, "You didn't Google this before you got up on a podium in front of the media."

[00:34:44] Scott Adams: So I'll quote Dr. Carmen Simon expert on memory. She teaches and writes about the fact that if you don't have a little bit of wrongness, people won't remember it. So if everything looks the same, your brain just falls asleep, say, "Eh, blah, blah, blah, blah, more of that," because your brain can't remember everything, right? It's very selective. And so there's something about President Trump's natural style, which I think he is intentionally elevated for these purposes, that everything seems to violate something that you didn't think should have been violated. He either acts in a way that you say, "No president should act that way," or he states something that you think, "That couldn't possibly be true." He uses a word that shouldn't be used in that context. There's just something about it, that's not normal. And he does that so consistently, it would be hard to think that that's completely accidental. Although I do imagine there are plenty of times where there's a small error and he just doesn't care. So some of it is not caring to make it exactly as people expect, but the net effect of it is, you can't turn away. If you tweet something, you just say, "Oh, that's more interesting than whatever else I was doing. Let's talk about that." And then it becomes part of your brain's architecture.

[00:35:56] Jordan Harbinger: How can we use this concept in our own lives, if we're not the president of the free world here? What do we do in our daily lives to maybe capitalize on the fact that, "Look, I want people to think this is important. How do I get it wrong, but not so wrong. I lose credibility?"

[00:36:11] Scott Adams: There must be infinite ways to do something slightly wrong. So I guess it would depend on the specific situation. If you're using hyperbole, let's say, let's use the classic example, let's say — well, for example, in this interview, I'm happy to see that at least 50 or 60 people who've showed up in the audience to watch us. I'm really happy about that.

[00:36:29] Jordan Harbinger: A million, million and a half, yeah.

[00:36:30] Scott Adams: If that ever gets fact checked and we find out that it's two—

[00:36:33] Jordan Harbinger: And they're both my parents, that would be — it's a little too farfetched.

[00:36:36] Scott Adams: Who's going to believe that anyway? But by the time somebody finds out that that fact was an exaggeration, they still have it in their head and they've lived with, "Well, I guess, there were a lot of people at that thing." And even the corrected information just doesn't have as much impact as the original thought. We don't like to change our mind that much.

[00:36:53] Jordan Harbinger: People think, "Why would he say that? Of course, he's going to get caught on that." And what you're saying is, "Yeah, but it doesn't matter if he gets caught on that," because the effect happens in the moment. It doesn't matter that later on down the line, it doesn't look accurate.

[00:37:05] Scott Adams: Well, he also uses the trick where he makes you think past the sale quite a bit. So there was a recent tweet where he, he said something like, "I can't imagine the Democrats if they voted against this. How would they live with themselves in the future?" And it makes you think about, "Well, could they live with themselves? Would that be hard in the future? What would that be like if you didn't vote for this? You know, that seems like an exaggeration. I think those Democrats would be fine because it's the way they voted. I'm sure they like that." So you're talking to yourself about this future, where they've got a problem and you've already thought past, did they make that vote? So he's making them think about their bad future, which is strong persuasion.

[00:37:43] Jordan Harbinger: What types of things can we learn from cognitive dissonance? This is one of the things that you start the book with. It's a concept we discuss a lot on the show. Can we define it and then talk about why it makes us irrational?

[00:37:55] Scott Adams: The Scott's definition of cognitive dissonance, without all the science in it, is that if there's something that violates your expectations or your self image, or just the way you think the world is supposed to be, especially if it involves you, that's the biggest trigger is, there something about you that you would have to . For example, if you found yourself doing something stupid, but you believe you're a very smart person, instead of saying, "Well, I guess, I was wrong. I must be stupid after all." It's far more likely to say, "Well, I had a good reason in this particular case, I didn't get asleep or whatever it was. Well, in that case, that might actually be the reason," so terrible example. But the point is that we spontaneously come up with a reason why everything was fine and our original opinion was just great.

[00:38:38] Jordan Harbinger: So essentially we've rationalized past opinions or behaviors in order to make them line up with preexisting beliefs.

[00:38:45] Scott Adams: Yeah. But rationalizing is almost too weak because cognitive dissonance can give you a full-blown hallucination in which you're seeing stuff you don't. The example I gave of the people who saw the two photographs of the security guard, the people who were deeply invested in how brilliant they were, because they had figured out this conspiracy that somehow the government had not told the people and they're way ahead of it. If their self-image is, "I could not be wrong about this, I get this sort of stuff all the time," and then there are clearly wrong. There's a photograph right in front of him that might cause them to hallucinate that they see the photo differently.

[00:39:18] Jordan Harbinger: So this essentially the rationalization of the hallucination gets us kind of back to zero. If we did have some evidence in our face that says, "You're so wrong about this, we have to kind of reset our expectations." We either have to change our entire identity, a way that we see ourselves, or we have to go, "What those photos? That's ridiculous. That's not the same guy." And that's just an easier calculation for our brains to make. Is that what you're saying?

[00:39:42] Scott Adams: The easiest thing your brain could do is to say, "I was right all along," instead of rework your entire history and yourself image and everything else. Let me tie this to something fun. I know I've talked about the idea that we're a simulated universe and that some creatures built us to believe we're right. The idea here — and by the way, they're credible people for your listeners who believe this.

[00:40:02] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, I think Elon Musk is one of them. Am I wrong about that?

[00:40:05] Scott Adams: I believe I heard that.

[00:40:06] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah.

[00:40:07] Scott Adams: They're scientists and philosophers who think, "This is worth the look." And the idea is that as soon as one species is smart enough to create a simulation that also thinks it's real, they'll probably make more than one. And they might make thousands of them, and maybe it's a game that kids can do. They can all make their own civilizations. So the odds are that it is very unlikely that we're an original species when there will be so many copies. So if we're a copy, then we're programmed. Meaning that there's somebody who's trying to conserve resources as all programmers do. It is unlikely that they would build a universe that had everything in it, just in case somebody saw it, that would not be any way to program anything. You would only do it as needed. But here's the fun part, you would also want to make sure that every person's experience was as easy to program as possible.

[00:40:54] So if you believed that we had lunch yesterday and I believe we didn't. And we get together, we realize we have different beliefs about this, one of us has to change. And it's much easier instead of having us rewrite our history and all that, and all the things that was connected to, for one of us to say, "Oh, now suddenly I'm spontaneously hallucinating that it was somebody who looked like you. And yeah, I got that confused." But none of that might be true in a simulated universe, the programmer is just trying to reconcile the problems without creating a permanent history that's objective.

[00:41:28] Jordan Harbinger: This is The Jordan Harbinger Show with our guest Scott Adams. We'll be right back.

[00:41:33] This episode is sponsored in part by Better Help online therapy. I know what you're thinking. "I don't need therapy. My friends are my therapists." Let me just tell you right now, your friends are sick of hearing about your crap. The therapist is a trained and objective professional, whereas a friend is not neutral. They have not received any training in working with mental health challenges. They're probably, like I said, kind of sick of hearing about the same crap over and over. While a friend can be a great source of social support, they are just not equipped to provide therapeutic services. Additionally, when you talk to a therapist, you have the comfort of knowing that they are bound by confidentiality standards and are going to go blab to everybody else in your group. Your friend could inadvertently or on purpose, spill your beans and make matters even worse. Further a therapist doesn't simply give you advice, rather, an effective therapist aims to help you establish goals, help you come to your own conclusions and realizations. So therapy is also where you can be vulnerable, process emotion. So if you've been avoiding therapy, because you think your friends are good enough, or they can be your therapist, consider this, right now, your sign to make an appointment today.

[00:42:31] Jen Harbinger: Our listeners get 10 percent off your first month of online therapy at betterhelp.com/jordan.

[00:42:36] Visit better-H-E-L-P.com/jordan and join over a million people who've taken charge of their mental health with the help of an experienced better health professional.

[00:42:44] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored by Blue Moon. Blue Moon is on a mission to bring some brightness back to your life. Break up that routine from its refreshing flavor with Valencia orange peel for a subtle sweetness and hints of coriander. Blue Moon Belgian White is a one of a kind beer. Blue Moon is here to break up the day to day and remind you of what life is like when you step out of your routine or like out of your freaking kitchen, where I've been for the last 18 months. My parents came for a two-week visit from Michigan to celebrate Jayden's second birthday. I took a little time off to hang with them. We enjoyed simple things like hanging out in our backyard patio, talking memories, sipping on a Blue Moon with good old dad. Those once in a Blue Moon moments should happen more than once in a blue moon. Blue Moon is carefully crafted for a one of a kind appearance and flavor. Coriander provides balance. Oats create a smooth creamy finish. The name stuck after a satisfied taster said, "A beer this good only comes around once in a blue moon." And I'm totally sure that really helped.

[00:43:34] Jen Harbinger: Reach for a Blue Moon when you're in need for some added brightness, get Blue Moon and Light Sky delivered by visiting get.bluemoonbeer.com/jordan to see your delivery options. That's get.bluemoonbeer.com/jordan. Blue Moon made brighter. Celebrate responsibly. Blue Moon Brewing Company, Golden Colorado, Ale.

[00:43:50] Jordan Harbinger: This episode is also sponsored in part by Progressive. Progressive helps you get a great rate on car insurance even if it's not with them, they have this nifty comparison tool that puts your rates side by side. So you choose a rate and coverage that works for you. Let's say you're interested in lowering your rate on car insurance, visit progressive.com to get a quote with all the coverage you want. You'll see Progressive's rate and then their tool will provide options from the other guys, all lined up and easy to compare so that all you have to do is choose the rate and coverage that you like. Progressive gives you options so you can make the best choice for you. You could be looking forward to saving money in the very near future. More money for say a pair of noise-canceling headphones, maybe you're going to upgrade your phone, I don't know, pay for an escape room or two, whatever brings you joy. Get a quote today at progressive.com. It's just one small step you can do today that can make a big impact on your budget tomorrow.

[00:44:36] Jen Harbinger: Progressive Casualty Insurance Company and affiliates. Comparison rates not available in all states or situations. Prices vary based on how you buy.

[00:44:43] Jordan Harbinger: Thanks so much for listening to the show. Your support of the show means the world to me. Of course, what keeps the lights on around here is when you support our sponsors. So please do consider supporting those who support us. Visit jordanharbinger.com/deals for all the codes, all those URLs. All those discounts are all in one place. jordanharbinger.com/deals.

[00:45:02] Don't forget. We've got worksheets for many episodes. If you want some of the drills, exercises, and takeaways talked about during the show, those are in one easy place in those worksheets, which are linked in the show notes at jordanharbinger.com/podcast.

[00:45:14] Now for the conclusion of my conversation with Scott Adams.

[00:45:18] So this is kind of like all eight levels or eight worlds of Mario Brothers do not exist inside the TV at one time. The only thing that exists is the frames you're looking at on the screen while you're playing. And if somebody else is playing Mario Brothers at the exact same time, they're playing their own game. It doesn't have to reconcile with whatever you're doing at home, in your living room, with whatever they're doing at home in their living room.

[00:45:40] Scott Adams: Bringing that to the human example. There are people who believe they're living in a country where a Hitler-like person has taken over and everything's going to go to hell soon. And there are people who think, "Oh, we're on the cusp of a golden age. Stock market is up." Those are completely different movies. The fascinating thing is that until something violates one of them, you know, until somebody sees something that you just can't explain away, the program doesn't need to reconcile them. We can just both live and procreate. And there was never any reason that we needed to reconcile them.

[00:46:11] Jordan Harbinger: How do we spot cognitive dissonance and then maybe short circuit it? Is it possible?

[00:46:17] Scott Adams: I think the best you can do is to figure out who got triggered at least more likely got triggered. If you'll allow me to use the election example, people who supported Trump were optimistic, he would get elected. They knew lots of people who voted for him. So when he got elected, there was nothing necessarily, that I can see, that would have triggered any kind of cognitive dissonance. But if you were positive this monster could never be elected and then he was, you have to rewrite your whole idea of the world you're living in. If members of those two groups disagree, it's more likely that the one who has an obvious trigger for cognitive dissonance is the one in it. That doesn't guarantee it because I suppose you could also be invisible to your own trigger, right? The whole point of cognitive dissonance is that when you're in it, you can't see it.

[00:47:02] But maybe — and this is really speculation on my part — maybe you could find the trigger and say, "Well, in this case, I had a trigger or the other person had a trigger," and that might give you a hint.

[00:47:12] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. Maybe. I mean, I thought for sure, this is going to be trouncing of the nth degree. And then when that didn't happen, I remember waking up and going, "I clearly live in a bubble where I only see people who have similar opinions to me. I need to fix that because this is so wildly wrong." I really thought it was going to be like, the whole long evening, I thought, "I'm going to be in bed as soon as I'm done with dinner, because it's not even going to be close and we're going to wake up with what we all thought was going to happen."

[00:47:39] Scott Adams: Now, based on your earlier comment, the fact that you are not strongly aligned with any particular group allowed you to reinterpret your situation fairly rationally. I mean, what you just said sounds totally rational to me. It's like, "Oh, I just realized I was in a bubble."

[00:47:54] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah. I just went, "Holy California, I got to travel more or something."

[00:47:57] Scott Adams: But you realize that 40 percent of the country said, "Russia. It had to be Russia," or, "They are way more racist than we ever imagined." So everybody came up with their own story about why they were wrong.

[00:48:08] Jordan Harbinger: Yeah, the racism thing made me quite sad. There were a lot of people that said anybody who voted for this person is racist. And I just thought like, "Whoa, I don't know if we want to run headlong down that track just yet." That seems — maybe I'm delusional again but I really don't want to think those types of negative things about the country that we live in. I don't want to bury my head in the sand if those things are true, but I also don't want to assume that people with different political beliefs are stupid or racist or really want to see the world burn. Although some of my friends who voted for either party were certainly in that camp too. I don't want to always assume the worst about somebody who disagrees with me, because I think that is a toxic mindset to have.

[00:48:47] Scott Adams: Both sides do, in fact, assume the worst. I think Republicans think that the people on the left are just crazy or selfish and the left thinks that are a bunch of racist, science deniers. I'm sure that's true of the extremes on both groups, but it certainly misses 85 percent of both groups.

[00:49:04] Jordan Harbinger: In Win Bigly, you have some tells that you talk about with rationalizations, things like looking at cognitive dissonance and saying, "All right, if we have a certain rationalization that is just beyond absurd, that's a tell." And then there was also different tells, the variety of tells that people have were also good indicators. Can you flesh that out for us?

[00:49:24] Scott Adams: My favorite one is on Twitter. You'll see somebody start the sentence with, "So," and then they'll misinterpret what you said as a, what I call a crazy absolute. It's an absurd absolute. So if you say, for example, "I'm in favor of guns," then somebody will say, "So, you're in favor of giving a toddler a loaded gun in a crib. Great, you idiot." And you think to yourself, "How could anybody have interpreted that as giving that extreme absurd absolute?" But the person I used to think that the person who would say such a thing is just a bad debater.

[00:49:59] Jordan Harbinger: Right. They just have logical fallacies they can't quite get—

[00:50:02] Scott Adams: Yeah, they're just saying whatever they need to say, because that's the other side. I now see that as they hit cognitive dissonance, because whatever I said must have erased all of their good reasons. They had to reinterpret what I said until it didn't make sense, so they could still be right. And when you watch somebody reinterpret what you say as an extreme absolute, it's like every time. So look for words, like, "Are you saying every time this happens? Are you saying that not one single time you've ever seen this?" As soon as you see that, you know that they've accepted your argument, at least it makes sense to them, but they can't live in that world. So they've got to rewrite their personal history.

[00:50:39] Jordan Harbinger: That sounds like me arguing with my wife. I know she's right. So I have to think of the most extreme situation in which she would be wrong. And that's the one I'm going to bring up in the car on the way here. And what about having lots of different explanations for the same thing. One of the tells that someone is engaged or indulging in cognitive dissonance was that there are — one person explains it this way and another person explains it that way. There's a hundred different explanations and they all kind of lead to the one conclusion.

[00:51:06] Scott Adams: Right. So right after the election, CNN published some long list of all the different reasons that people got it wrong and Trump actually won and they're all different. And if you see that many different reasons for something, it means that nobody knows the reason, which means that maybe they don't want to accept the reason. That's a red flag when you see lots of different explanations and everybody's looking at the same data, that's the thing. If everybody were looking at different information, then different explanations make sense. But if they're looking at the same stuff and they've had the same brains and they've got 24 different reasons to explain it, probably none of them are right.

[00:51:43] Jordan Harbinger: But can't there be multiple explanations for the same phenomenon or for the same result?

[00:51:49] Scott Adams: Well, there are multiple variables. So you could have a situation where lots of things, where two percent of the answer, but when you're trying to sell it as the reason, it would be reasonable to say, "Okay, well, there are a whole bunch of things and maybe this was two percent and this was one percent." Had somebody said that I would say, "Oh, that's a reasonable person who is not in cognitive dissonance at all." When you look into it and there are so many different things and you say, "Well, the reason is sexism."

[00:52:15] Jordan Harbinger: Right. Hillary ran a bad campaign and sexism and racism. Those could all be right though, right?

[00:52:20] Scott Adams: Well, they can all be one percent, two percent of the problem, and they're all complicated because it could work both ways in some cases. And if anybody says the complicated version like, "Well, there are many variables, we can suss it out," what I said was, "The persuasion would be a better predictor." And then it did in fact, predict a number of things along the way as well as the final result. But I still present that with all the humility that I can muster as what I call a filter. That is to say, it seems to me that we don't really have a good sense of reality. Nobody does. You know, we all have movies in our heads that are a personal reality. So the experiment was, if you pick this variable, does it help you predict better than other filters on the world? So it doesn't mean it's true. It doesn't mean there's even an objective reality necessarily, but we can observe because I predicted publicly and I said, "I predict this, and then you can see if it was true," and they were good predictions.

[00:53:15] Jordan Harbinger: Right, because there's a lot of folks out there that go, "All right, guy gets lucky, predicting a Trump win. Now, I got a freaking book in front of me. Come on, man. You're giving yourself too much credit." And it sounds like what you're saying is, "Maybe. We'll never know."

[00:53:28] Scott Adams: I always make fun of the fact that when somebody becomes a millionaire or they start a company everything goes right, and then the first thing to do is write a book. It's like, "Well, everything I did must be the right thing to do." Of course, there's just no logic to that. Some people were going to succeed. There were a thousand variables. Every one of them had to line up to make this happen. You should be cautious of someone who writes a book and says, "I succeeded. And therefore you should do it this way." So I tried to write books that say, "Here's the process. You can try it yourself. It doesn't cost you anything. Compare it to what you are doing, make your own decision."

[00:54:01] Jordan Harbinger: Sometimes you hear entrepreneurs say things like, "You know, just follow your passion." But the problem is when Mark Cuban or somebody says something like that, he can say that and we see it because he's on Shark Tank. There's a lot of other people who believe the same thing and they live in the basement on their mom's couch because that's not good advice, but it sounds really good. And it certainly sounds better than, "Be in the right place at the right time. Work really hard. Here's how you manage a team of talented employees. Here's how you recruit those employees. Here's how you outsource manufacturing to China in a cost-effective way — no, no, no, no. Screw that. Follow your dreams. Where's my check?"

[00:54:33] Scott Adams: Yeah. Then nobody wants to admit that luck is a gigantic factor. So the way I dealt with luck in my own career is I tried lots and lots of stuff, and I waited for something to catch on, but in advance, you'd never really know which one's going to work.

[00:54:47] Jordan Harbinger: We had somebody on the show in the past. He talked about the role of luck and how, when he was doing studies of entrepreneurs and things like that, we all minimize the role that luck plays in anything that actually gives us an advantage. Because as a culture, we don't look at things that are considered lucky and say, "This is a good thing to have on my side," because we don't believe in magic and things like that. It's a very Western concept. Whereas if we do look at luck and we go, "Wow, I am so lucky that I started this podcast and that I learned good work ethic from my father and I stuck with it. And then I got laid off from my law job. That was actually lucky. And then I kept doing this and now I'm in this great place and interviewing all these great writers and things like that." That looks like luck, if you really examine all these right things that fell into place. But it's much nicer for me, my ego to say, "Actually, you know, I just had a really good vision and I stuck to it because I'm very tenacious and I'm a hard worker and all these other things happen to me, but I persevered anyway. No, luck? Of course not. I earned all this."

[00:55:44] Scott Adams: There's also a weird connection between perceived luck and your attitude. So there actually were studies — Dr. Richard Weisman studied, whether people had luck. He found that you can fake luck, meaning that if you say to yourself, "I'm lucky. Something good is going to happen." It turns out and it changes your perceptual abilities. It sets your filter differently. So if you expect luck, even if you're just talking yourself into it, you're more likely to notice something or even maybe do something a little bit differently. So it's sort of a way of programming yourself to notice luck that was going to happen no matter what. You just wouldn't have noticed before.

[00:56:23] Jordan Harbinger: Is that called the reticular activation system?

[00:56:25] Scott Adams: Yeah. That's one of the names for it. For example, pick out your name and a crowd when everything else is just crowd noise. Once you set your focus on something, you just start noticing those things, which matter to that focus. And that's fairly well-documented.

[00:56:39] Jordan Harbinger: Why do you hate analogies so much? I use analogies all the time on the show to teach and illustrate concepts. And I'll often get an email, "Scott Adam says that analogies if you use those, you've already lost."

[00:56:50] Scott Adams: Probably nothing is more misunderstood than my view of analogies. Let me see if I can, for the first time ever, clearly explain what I mean. Analogies for explaining a new concept are excellent. So I'm not saying analogies are bad all the time. I'm saying that nobody ever won an argument with an analogy. So nobody ever said, "Well, you've got a mustache, Hitler had a mustache, apparently you're going to invade Poland." So that's the sort of way people try to win an argument with analogy. If you're trying to describe a zebra to someone who'd never seen it, you say, "Wow, it's like a horse. Imagine you painted some stripes on it and it would get you there faster." So analogies, excellent way to describe a new concept, but you're never going to win an argument with an analogy.

[00:57:32] Jordan Harbinger: Because you're arguing about something that you've set up, that isn't what you're actually arguing about.

[00:57:37] Scott Adams: Every analogy gives the opponent infinite ammunition to attack because the analogy is imperfect by its design. That's what an analogy is. It's not the thing is, something that just has something in common with the thing. So you know that your opponent who is not going to be swayed at all is going to say, "Well, look at all the problems with that and analogy. ABC, it's completely different because of this." You can never get to the end of that path. So analogies are useless.

[00:58:02] Jordan Harbinger: There's so much in Win Bigly that has to do with persuasion and things like the power of slogans, the power of color association, the power of contrast. I'd like to wrap with the concept of strategic ambiguity. Because as soon as I heard that I went, "Oh my God, I think I see this all the time. And I think I use this all the time and never knew what that was called." Can we talk about why this is so effective? Well, first of all, what is it and why is it so effective?

[00:58:27] Scott Adams: So strategic ambiguity, the way I use it in this context is when you present — let's say, a politician says, "I want to do this or that," stated in a way that everybody gets to hear what they wanted to hear.

[00:58:41] Jordan Harbinger: I just don't want people to go, "This is all BS, because we're talking about somebody I don't like," because then the whole thing is lost. But I think Trump's examples are perfect for this because he's the one using it and this is what the book is about.

[00:58:52] Scott Adams: There are people who think that he is super tough on immigration because he's a racist. In other words, they are racist themselves and they probably think, "Hey, this is great. We found one of our own," but there are people who are not racist, just regular Republicans who don't see anything like that. They just say, "Border control is just normal business for protecting the country." Their frame is completely different, but both of them can see in the way that the president talks their own message.

[00:59:22] Now, some are going to call that the secret racist dog whistle, but I would say that the secret whistle is present anytime there's ambiguity. Anytime there's any lack of clarity, people are putting their own interpretation on it. If it happens to be a topic of racism and people hear the magic whistle. If it's some other topic, then they just get a different opinion about what the person said. But since we're kind of locked into our previous opinions of the world, any ambiguity, it lets you see whatever you want to see.

[00:59:52] Jordan Harbinger: Basically, our mind fills in the blanks. And if we're strategic about our ambiguity, we're saying, or doing something deliberately so that other people's minds will fill in the blanks.